Dialogue

An Uncomfortable Mormon

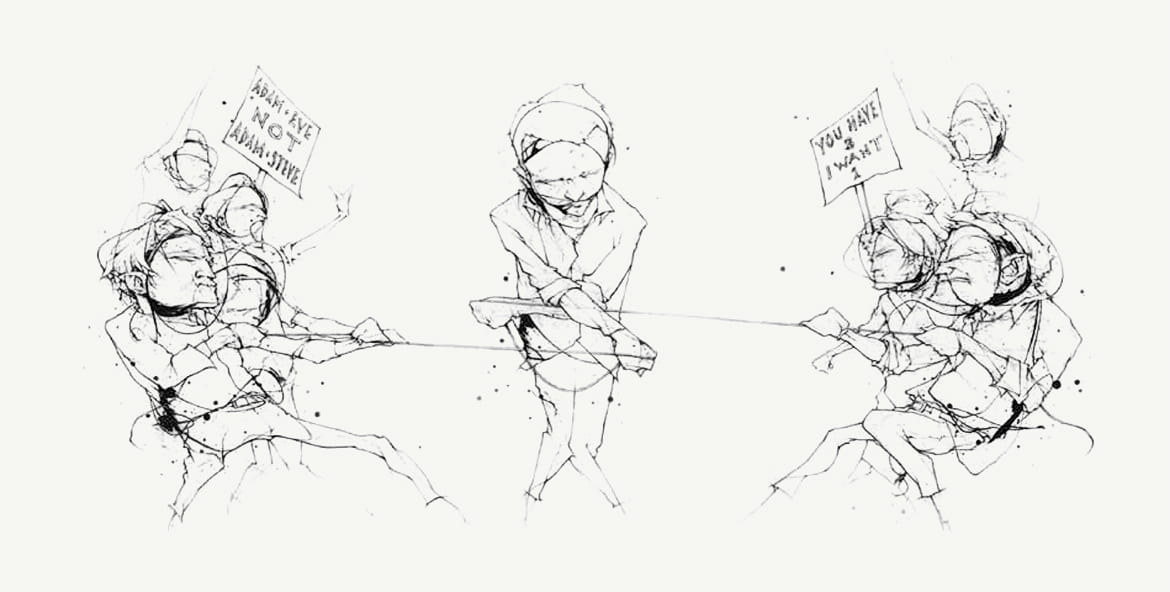

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

By Taylor Petrey

The year 2008 was a terrible one for Mormons. Perhaps we should have known it would be, since the year started off with the death on January 27 of Gordon B. Hinckley, who had been the leader of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) for nearly 13 years. Hinckley oversaw an extensive expansion of the Church, as well as a public-relations overhaul and, during his tenure, Mormons enjoyed a relative amount of good press and social acceptance. I daresay most of us thought this would continue, but the media had other ideas.

Not even a full year after Hinckley’s passing, Tom Hanks, the executive producer of HBO’s polygamist series, Big Love, chose the night of its premiere to make this comment: “The truth is [Big Love] takes place in Utah, the truth is these people are some bizarre offshoot of the Mormon Church, and the truth is a lot of Mormons gave a lot of money to the Church to make Prop-8 happen.” He continued, “There are a lot of people who feel that is un-American, and I am one of them.”1 In this public statement, Hanks brings together polygamy, Proposition 8, and, in a Palin-esque rhetorical move, the assertion that Mormons are not quite American. Despite the pluralistic ideology of American identity, this construction of Mormons as “un-American” has a long history in American discourse,2 an unfortunate history that has been brought back to us forcefully in recent months.

As it turns out, Mitt Romney’s presidential candidacy was a mixed blessing in that it both challenged and exposed popular sentiment about Mormons. Even for many Mormons who disagree with Romney’s politics, and/or who were disappointed by what they viewed as his calculated move to the right on social issues (seen by some to be an attempt to appease an evangelical base who was greatly concerned by his Mormonism), it was still a proud moment for Mormons to have a member of the tribe in the running for the presidency. It was a tantalizing thought that we might have Romney as the highest-ranking leader in the land, at the same time we had Harry Reid (also a Mormon), as the Senate majority leader, the highest-ranking Democrat in the country. How would that have been for demonstrating the internal diversity within Mormonism?

After all, it was a hopeful election, because of the many boundary breakings it symbolized. As the United States was facing down racism and sexism, there was hope that the latent anti-Mormonism that has been so constitutive of American culture was finally thawing, too. In a country where there had once been an extermination order on Mormons, and a hot and cold war between the federal government and the Utah territory, the idea that a Mormon could be considered for president was a source of hope and pride.

The letdown was all the greater, then, when the press coverage of Romney’s religion was anything but warm toward Mormons. This disappointment was captured in a Boston Globe editorial by Whitney Johnson: “[W]e have worked so hard to assimilate, we have even been able to convince ourselves that we are accepted. With Romney in the national spotlight, it has become all too clear we aren’t. This is a discovery we would have preferred not to make.”3

The next public relations challenge that hit the Mormon community was the high-profile raid in Texas on a polygamous compound of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (FLDS), a group that splintered from the LDS Church in the early 1900s, not long after the main body of the Church abandoned polygamy in 1890. While this story had absolutely nothing to do with Mormons, the link between these polygamous sects and the main branch of Mormons is still quite close in the popular imagination. Polls show that as many as 36 percent of Americans believed that Mormons operated the polygamous compound.4 Press coverage persistently encouraged these associations, implicitly and explicitly connecting the two.

Finally, there was Proposition 8 in California, a proposed state constitutional amendment designed to overturn the Supreme Court of California’s decision to legalize and protect same-sex marriages. The LDS Church officially encouraged its members in California to “do all you can to support the proposed constitutional amendment by donating of your means and time to assure that marriage in California is legally defined as being between a man and a woman.”5 In my lifetime, no other issue has so divided Latter-day Saints from within than the official opposition to same-sex marriage. Many Mormons feel torn between their commitments to marriage equality and their spiritual and social community. Many more feel defensive about the deliberate, strategic targeting of Mormons by proponents of same-sex marriage, both pre- and postelection. The result was that very little ground was left for Latter-day Saints who support same-sex marriages.6

In the aftermath of the referendum’s passage by California voters, the LDS Church was the target of bitter protests by a subset of activists at temples all across the country. Such a response had the unfortunate effect of appearing to confirm the fears of many who worried that same-sex marriages would infringe on religious exceptions of conscience to perform such unions. These efforts were ineffective if the goal was to persuade Mormons, though they did effectively exploit Mormon vulnerabilities as a suspect group. In a related example, Rosemary Radford Ruether said of Mormon feminism in 2007: “I do not intend to engage in ideology critique of Mormonism because I regard this as the job of Latter-day Saints, not that of persons outside the LDS tradition. The purpose of ideology critique of a religious tradition is for the sake of pruning away its distortions in order to reclaim its liberating core and potential. This work can be done only by those within and committed to particular communities and traditions, not those outside and against them.”7 Radford Ruether offers not only a warning on the limited value of outsider critique, but also calls on insiders to take up this challenge themselves, which remains to be done in the LDS Church.

Instead, I fear that the broad brushstrokes applied to both sides of this issue only entrenched them further. The unfortunate “culture war” rhetoric polarized the issue by depicting each side as engaged in an attempt to destroy the other’s way of life, but the reality was more complex. Though many activists unhesitatingly portrayed the LDS Church as a homophobic and bigoted institution, this had been a time of some progress for the Church on gay rights issues. The LDS Church had publicly reversed its opposition to civil unions and supported California’s domestic partnerships, which was a moderating departure from the original stance of ProtectMarriage.com, the official Yes on 8 website, which had initially opposed domestic partnerships and civil unions.

I do not intend to depict Latter-day Saints as simple victims in this situation. Certainly many of those involved in the Prop 8 debate provoked a response. Often the LDS Church is its own worst enemy in its public image problems. However, I do feel that the troubling ways that Mormons were portrayed (and the ways Mormons sometimes portrayed others) this past year underscored our collective desires for a neatly divided world where we recognize the good guys from the bad guys, the goats from the sheep.

The world as it is challenges this. If we are honest with ourselves, we have to admit that the luxury of moral absolutes is something that we rarely enjoy. This is not to say that there is no such thing as good and evil, only that the boundaries are not as clearly marked as we sometimes like to think. History is filled with great, inspiring personalities whose ideas or actions were responsible for problematic outcomes. All of our heroes are morally ambiguous to some degree. Even for Mormons, to claim Joseph Smith was a prophet by no means claims that he was a perfect person.

At the same time, such a condition of necessary imperfection can be redemptive. For Christians, if we take seriously the Pauline notion that “all have sinned, and come short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23), we are called to grapple with complexity, ambiguity, and the gray areas, to do the hard intellectual and spiritual work of the responsibility of Christian life. In doing this work, we are able to develop the virtues of faith, hope, and love (I Corinthians 13:13). We develop compassion, forgiveness, patience, and understanding, not only for our perceived enemies, but also for ourselves.

For me, the experience of being a Mormon in the United States in 2008 contained within it a powerful spiritual lesson. I learned how to be more comfortable with being uncomfortable in the ambiguity and ambivalence of the world. Above all, I came to see the great, gaping need for love and understanding if we are to move forward.

Notes:

- Tom Hanks later retracted his remarks in People magazine.

- Terryl Givens, Viper on the Hearth: Mormons, Myths, and the Construction of Heresy (Oxford University Press, 1997).

- Whitney Johnson, “Romney, Mormons, and Me,” The Boston Globe, February 9, 2008.

- Howard Berkus, “Polygamist Raid Is PR Nightmare for Mormons,” National Public Radio, June 30, 2008.

- “Preserving Traditional Marriage and Strengthening Families” June 29, 2008, newsroom.lds.org/ldsnewsroom/eng/commentary/california-and-same-sex-marriage.

- Many LDS members sought to create this ground within the Church. For instance, see mormonsformarriage.com.

- Rosemary Radford Ruether, “A Dialogue on Feminist Theology,” in Mormonism in Dialogue With Contemporary Christian Theologies, ed. David Paulsen and Donald Musser (University Press, 2007), 297-298.

Taylor Petrey, who received his MTS in 2003, is currently a ThD student at HDS. He is studying New Testament and Early Christianity and is writing his dissertation on the resurrection. A version of this article was delivered at Wednesday Noon Service on January 31, 2009, in Andover Chapel.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.