Dialogue

A New Voice in Darfur

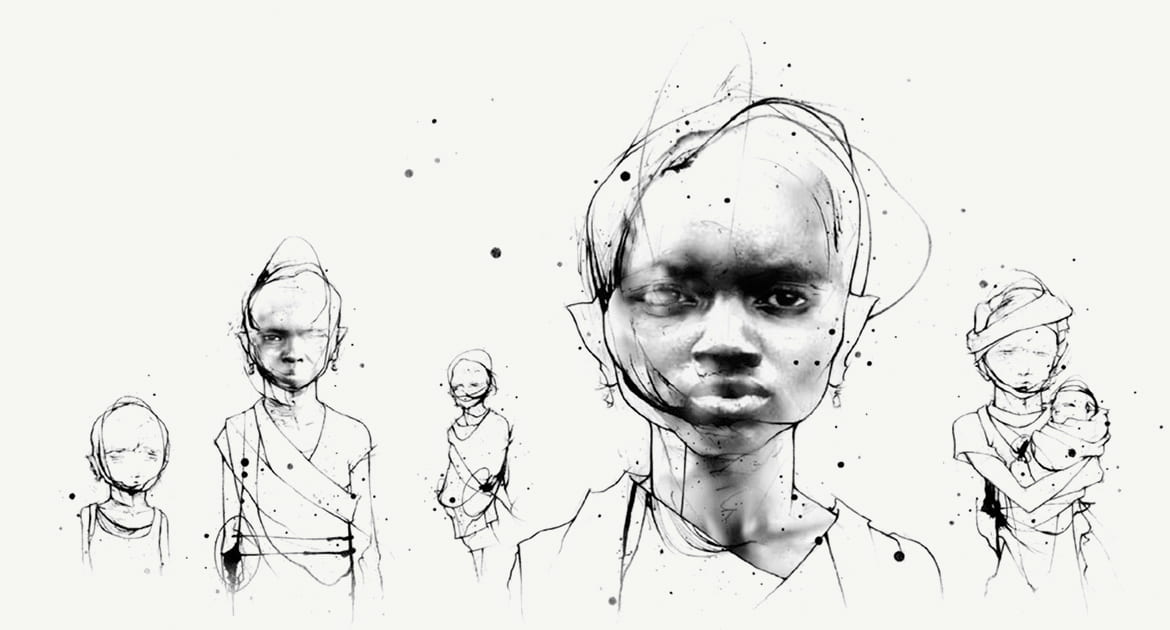

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

By Chris Herlinger

Arguments about numbers—of the dead, the living, the displaced—have so dominated the international debate about Darfur that it is sometimes easy to forget that behind the numbers are real human beings. And real human beings will have to live out the consequences of actions taken or not taken in the coming months and years ahead about Darfur’s future.

I recently returned to Darfur after a three-year absence—just a few weeks before the start of the October peace talks that quickly stalled—and was immediately struck by how the human element in the Darfur “narrative” has sometimes become lost amid debates about genocide and whether the Darfur crisis should be viewed through the prism of continued humanitarian action or the need for a political settlement.

At the very least, the food, shelter, and medical care being provided to Darfur’s displaced by a variety of religious- and secular-based relief and aid groups is still needed. Such efforts are helping sustain and save lives. But that balm cannot be sustained indefinitely, which is why a political settlement that begins to address Darfur’s long-standing social problems must also begin to take shape.

That need has been heightened in recent months because the situation in Darfur has both changed and worsened. Humanitarian workers describe the situation as spinning out of control, with rebel groups that had been fighting the government of Sudan and allied Janjaweed militias now splintering off and fighting each other, presumably trying to control territory before a “hybrid” force of United Nations and African Union peacekeepers arrives in early this year.

This dynamic is playing out while survivors of this violence and the still-continuing (if declining) displacement of villages by Sudanese militias and the Janjaweed continue to stream into camps for the displaced. These camps are becoming permanent features of Darfur’s brutalized and blighted landscape: about one-third of Darfur’s 6.4 million residents—four times the population of Boston—are now displaced, according to United Nations estimates.

One of those displaced is Mariam, a 40-year-old mother of five and grandmother of one.

I met Mariam in September in a camp on the outskirts of Zalingei, a small West Darfur city whose population has swelled in recent years with the growing influx of uprooted persons. Mariam looked a good decade, or even two, older than 40, and she had arrived in the camps only months before. Like many other women in this and other camps in Darfur, Mariam was no stranger to Darfur’s terrors: she had been displaced some eight months earlier after attacks she said were perpetrated by government and Janjaweed militias. Among those killed were Mariam’s husband and her son-in-law.

“It’s a difficult life,” Mariam said as she stood outside the entrance of the small, thatched-roofed mud home where she lives with her children and granddaughter. “We don’t have anything.”

Mariam spoke slowly and deliberately with a touch of impatience—her understandable concern was in tending to the needs of her family, and she had things to do. She was trying to resolve a dispute over food rations, all while acting as the family’s sole breadwinner, selling okra and watermelon in a local market.

Yet even with these attendant problems, as well as the very real threat of sexual assault women face as they try to gather firewood outside of the camp’s perimeters, Mariam said she had no plans to leave the camp. Her resoluteness is not only due to her finding a small measure of safety in a camp where, rightly or naïvely, camp residents feel the presence of humanitarian personnel offers some type of protection. It is also because, as Mariam looks beyond the camp borders, she is not convinced her home village will ever be fully safe again.

And there is another issue, which touches on the need for a long-term political settlement in Darfur. Even with all of its attendant tensions and terror, its confinements and claustrophobia, Mariam’s camp offers something her own village never had: free schooling for her children.

That is no small matter in a region where education has often been out of reach or unavailable for the rural poor, and indeed it points to one of the issues that rebel groups in Darfur have cited as a cause of grievance against the Sudanese government: Khartoum’s long-standing neglect of Darfur.1

Such grievances were not spoken of when I visited the camps in 2004. Indeed, a lingering memory of that visit was the state of almost ineffable trauma and ennui that seemed to grip the camps. It made speaking to people, particularly women, difficult and even painful. Not so in September 2007. In a striking contrast, people in the camps were frustrated and angry—and they were not afraid to speak freely about their frustrations and anger.

This was most visible among women, who in one camp had begun organizing themselves to improve day-to-day conditions. Such changes were certainly needed. It was disheartening to visit a camp I had seen three years earlier and learn that, even with the camp population increasing, a single clinic and dispensary continued to serve a population of about 60,000.

If there was a face to this new development it was Fatima, whose outspokenness and anger evoked in me the memory of the American civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer. Fatima was not afraid to spell out a litany of grievances about camp conditions to a group of visitors from American and European church-based humanitarian groups. “The needs are still great,” she told us, and she waved her fist as she declared the need for the United Nations peacekeeping force to protect those in the camps. “We’re tired of living in this prison.”

Even more amazing was Fatima’s boldness in saying she and others in the camps supported the militancy of Abdul Wahid Nur, a founder and leader of the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and a notable holdout in not attending the October peace talks because, he said, security cannot yet be guaranteed in Darfur. (Mention of Wahid Nur’s name evoked loud shouts and applause; Fatima was hardly Wahid Nur’s sole supporter in the camp.)

It was hard not to feel that Fatima and other women in the camp represented a new voice in Darfur: a militant and agitated anger that, for now, may have nowhere to go. It is hard to see how this deeply felt but politically inchoate force can become a “movement” to influence the peace negotiations—the camps are too isolated from one another and people there are not leaving because of fears for their own safety.

But then maybe not: knowing that such anger is brewing in the camps may contribute to some kind of leverage at future peace negotiations. “The government feels this hostility all around them,” one official of an international aid agency told me.

Whatever is eventually decided, the long-term prognosis for Darfur will depend on providing Mariam, Fatima, and their families—real people with concrete needs—the tools to rebuild their lives and find a measure of dignity, security, and hope. A displacement camp, after all, should not be the only place in Darfur where it is possible to find things like free schools or easy access to water.

Chris Herlinger is a New York–based freelance journalist and writer for the humanitarian organization Church World Service. He was a resident fellow at Harvard Divinity School in spring 2005, and won the Catholic Relief Services 2006 Egan Award for his reporting from Darfur for National Catholic Reporter.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.