From the Archive

A ‘Christo-morphic’ View of Religion

By Richard Reinhold Niebuhr

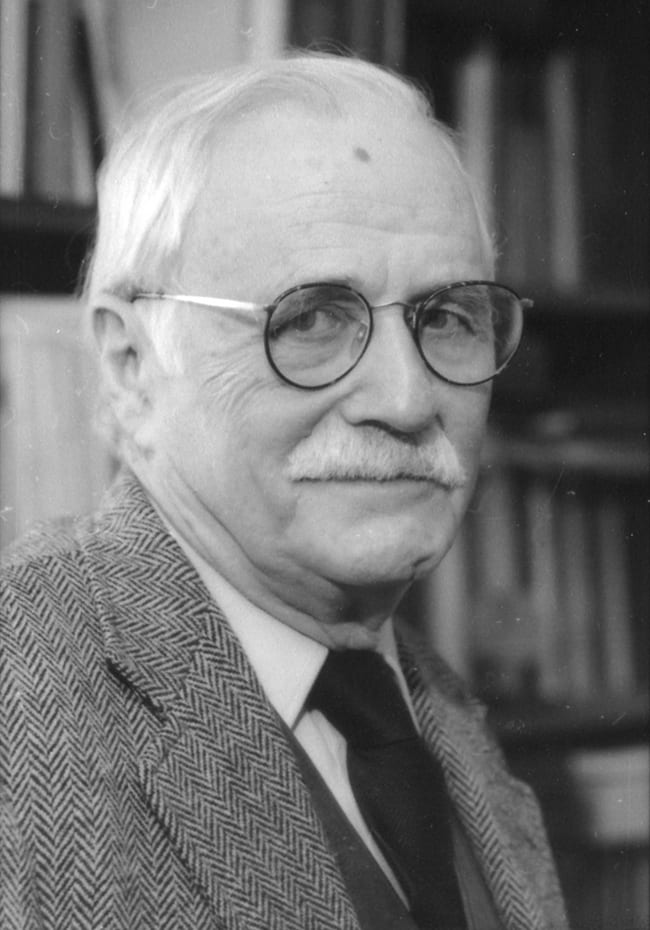

Longtime Harvard Divinity School professor Richard Reinhold Niebuhr, Hollis Professor of Divinity Emeritus, passed away on February 26, 2017, at the age of 90. Niebuhr was a renowned theologian, researcher, and scholar, as well as an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ. He began teaching at HDS in 1956. To honor him, we reprint here an excerpt from “Religion and the Finality of Christianity,” a lecture he delivered at the 1963 Ministers’ Institute. It was published in the April 1963 issue of Harvard Divinity Bulletin.

The mistake of Barthiamism is that it has misunderstood revelation. Revelation, which is not a word that occurs with any great frequency in the New Testament in any case, is not the impartation of knowledge of God primarily. The word, revelation, is a noun, in itself an abstract concept, which becomes concrete and significant when it is coupled to the historical figure of Jesus.

Jesus of Nazareth, in turn, as the New Testament depicts him, is a man who fully is a man of his times. He moves among his disciples and countrymen as one who has an authority greater than that of the prophets or Moses and who claims that the power of the rule of God is present in himself. He makes messianic claims for himself, and in this sense he is without equal. At the same time, however, he enters into the sphere of human religion. He initiates quarrels with the professional religious men of his time, for example the Pharisees, and chastises them, not because they are religious men, but because their religion has become distorted and alienated from the spirit of the faith of Abraham and the prophets. He meets the woman of Samaria, whom he obviously treats as one already related to God, and reprimands her; he greets the gentile Roman centurion who sends for him to heal his slave and says, “Truly not in all Israel have I found such faith.” These and other similar incidents stud the basic gospel narrative of the ministry, suffering, dying and rising of Jesus of Nazereth.

In the light of such pericopes as these (and in the light of Paul’s missionary activities including his preaching on Mars’ Hill in Athens) it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to resist the conclusion that Jesus himself, as the early Church recalled him, took human religion very seriously; and insofar as we can attach to him the title of revealer of God or describe his mission and history as divine revelation, we must be careful to perceive and remember that the content of the word, revelation, is Jesus of Nazareth, descended from David according to the flesh and declared to be the Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection. The content of revelation is the history of Jesus, and the history of Jesus is the history of a messiah who came preaching repentance (metanoia) or change of mind. Thus, insofar as Jesus was dealing with humanity, he was not imparting new doctrine about God but exhorting and effecting change of mind and heart toward God. He was moving among and confronting a humanity already related to God, a religious humanity, and transforming that religious humanity through metanoia. Consequently, we should have to say that revelation is not the contradiction of homo religiosus but rather the renewal and transformation of religion. . . .

. . . Insofar as I have any understanding of Christ, he is not the abolition of my religion, nor does he teach me that my religiousness is my sin. Neither does he transport me above the vicissitudes and ambiguities and vanities of human history and hence of religion. Rather, he throws me back upon my sheer humanity and—to borrow a phrase from Schleiermacher—upon my absolute dependence on God. Therefore, if he brings me peace, he brings it with a sword, but he can bring me neither except insofar as I am a religious being. . . . It is not simply Christ that I see—my religion has not become a religion of Christ. He is not the center of my world and I am not a Christo-centric man. Rather, it is with and through Christ that I see, so that he has become the form, the exemplar, through which the distortions of humanity are laid bare and the destiny of man is adumbrated. My religion has become not Christo-centric now but rather Christo-morphic. And insofar as the ultimate religion of the Bible is contained in the Psalmist’s words: “My times are in thy hand,” I recognize that henceforth all time for me will be informed and conformed and reformed by the image of Christ.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Thank you!