Featured

Toward a More Radically Inclusive ‘We’

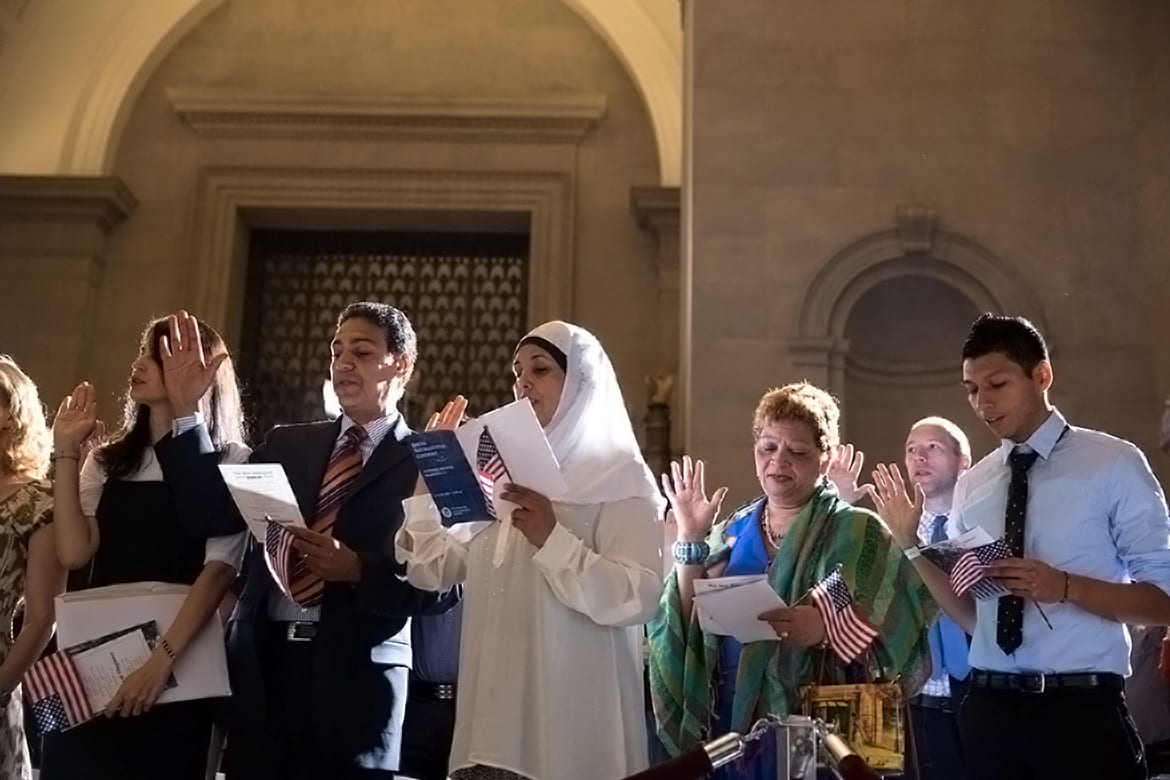

Naturalization Ceremony, US Archives.

By Diane L. Moore

We often say that we are a nation of immigrants.

This common phrase has been echoed throughout the history of the United States and is itself one of the defining pillars of American identity. It captures the rich histories of migrants from across the globe who have traveled to our shores over centuries, inspired by a dizzying array of motivations, including, but not limited to, seeking refuge, security, reunion with family, and relative prosperity. So in this sense, the assertion that we are a nation of immigrants is absolutely true.

However, this phrase masks two other pillars of American history that are also critical to our identity: 1) the genocide of Native peoples who populated this continent for centuries long before the arrival and eventual colonization by Europeans; and 2) the prolonged forced migration of Africans through the heinous institution of chattel slavery. To say that we are a nation of immigrants masks these two other pillars of American identity in ways that hinder our capacity both to learn from and to come to terms with this complicated and devastating history. Regarding the relevance of religion in these phenomena, dominant strands of Christian expression (for example) gave sanction to colonialism, genocide, and slavery, while other strands of Christian expression challenged them. Understanding these influences is an important dimension in understanding the foundations of U.S. identity.

While keeping in mind the pillars of genocide and chattel slavery, I want to focus for a moment on the third pillar (that we are a nation of immigrants), through two vignettes from our history.

The first is a remarkable exchange of letters from 1790 between Moses Seixas, the Jewish warden of a synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, and President George Washington. The occasion was Washington’s visit to Rhode Island shortly after citizens voted to ratify the Constitution. Washington was met by a cluster of local dignitaries upon his arrival, and Seixas was among those greeting the president. Here is an excerpt from the letter Moses Seixas presented and read publicly:

Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events behold a Government, erected by the Majesty of the People—a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance—but generously affording to all Liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship:—deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language equal parts of the great governmental Machine. . . .1

A few days later, Washington responded in a return letter to Moses Seixas with these words:

The Citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship. It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

These comments are clearly aspirational and clearly far from realized at the time of their utterance, when Native peoples were continually persecuted and displaced, and chattel slavery was in full force. When viewed through these realities, those lofty aspirations are exposed as blatantly hypocritical, hollow, and even sinister. Is there any hope that we as a people could truly erect a government that “gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance,” given these foundations? I believe we can, but not until we confront these legacies and the devastations they have wrought. At the heart of the matter, of course, is who is included in our “we.”

The second vignette focuses on the Statue of Liberty that stands as an iconic symbol of the assertion that we are a nation of immigrants. The inscription at the base is adopted from a poem by Emma Lazarus, who was born in 1849 into a Sephardic Jewish family and whose great-great-uncle was Moses Seixas. The inscription reads as follows: “Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, / The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. / Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, / I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

It seems to me that one of the ways to atone for the two devastations of our three pillars of identity—the devastations of genocide and chattel slavery—is that we relentlessly and vigorously embrace a more inclusive version of our third pillar: that “we” are a nation of immigrants, Native peoples, descendants of colonizers, slave owners, and slaves; and that “we” will aspire to give to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance; and that “we” will embrace and recognize as our own the tired, the poor, and the huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

Notes:

- The 1790 letters are available on the Facing History and Ourselves “Give Bigotry No Sanction” project website.

Diane L. Moore is the founding director of the Religious Literacy Project at Harvard Divinity School, a senior fellow at the Center for the Study of World Religions, and a Faculty Affiliate of the Middle East Initiative. She served on a task force at the US State Department in the Office of Religion and Global Affairs in the Obama Administration to enhance training about religion for Foreign Service officers and other State Department personnel.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.