In Review

The Reader, the Evangelists, and the Wardrobe

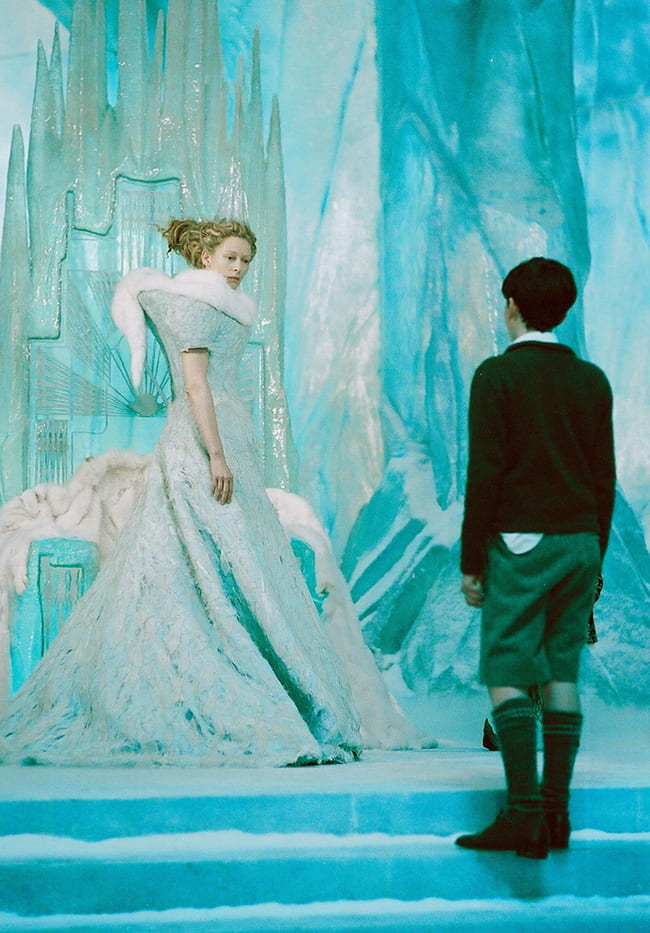

The Chronicles of Narnia. Disney Enterprises, Inc. and Walden Media LLC.

By Mark Pinsky

For all its toxic, ultra-violent, and hyper-sexualized faults, popular culture sometimes offers an engaging opportunity to talk about faith, religion, and spirituality. Pastors and youth leaders are convinced that it is possible to arrive at a serious discussion about these topics—despite beginning with a sometimes-silly premise. Using popular culture as a reference point enables them to reach people, especially young people, where they are in our media-drenched environment.

I’ve had plenty of experience in this regard, looking for deeper meaning—including the subtle difference between animating faith and caricaturing it—in Disney’s cartoon features and in The Simpsons, for example. To be sure, as a number of cultural and theological critics have pointed out, occasionally to me, some of these interpretations are a stretch. And I admit there are limits. For example, my argument that the foul-mouthed cartoon series South Park, on cable television’s Comedy Central channel, is the place where scatology meets eschatology has thus far fallen on deaf ears. Still, there is no denying that, from The Gospel According to Peanuts, 40 years ago, to The Gospel According to Oprah last fall, such books have popular appeal. And when the subjects of these interpretations are blockbuster movies like the Matrix or Lord of the Rings trilogies, or even more durable franchises like Star Wars or Harry Potter, the interest in spiritual or theological interpretations is even greater.

Religion professors may bemoan this trend as further evidence that we are living in an age of superficiality, of evaporating attention spans and the concomitant dumbing down of discourse. But now has come a far more problematic subject than TV’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer. On December 9, Walt Disney Pictures and Walden Media released The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, a $150-million movie version of the first book in C. S. Lewis’s beloved seven-novel children’s epic and Christian allegory. On the cover of my new paperback copy of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is an orange circle the size of a silver dollar that reads, “A Major Motion Picture/Holiday 2005.” This blurb may be the subtlest of the tie-ins, which range from plush toys to video games.

In the months leading up to the film’s pre-Christmas release, media attention focused on Disney’s delicate predicament. The studio reached out to the large evangelical market by hiring some of the same firms that worked with Mel Gibson on The Passion of the Christ, to emphasize the film’s Christian content. At the same time, Disney executives downplayed the effort, to avoid scaring off the even larger pool of mainstream moviegoers.

Amid the megamarketing of a movie may lie a battle for theological custody of C.S. Lewis’s legacy

This is not a new concern. The publishing group HarperCollins controls most United States rights to both the Narnia series, which has sold 90 million copies since it was first published in 1950, and Lewis’s hugely popular apologetic Mere Christianity. In 2001, the company ignited a controversy when someone leaked an internal memo to The New York Times about plans to commission new Narnia adventures that de-emphasized the Christian content. “We’ll need to be able to give emphatic assurances that no attempt will be made to correlate the stories to Christian imagery and theology,” wrote an anonymous executive of HarperSanFrancisco. Lisa Herling, a spokeswoman for the parent publishing house, did not deny the accuracy of the memo. “The goal of HarperCollins is to publish the works of C. S. Lewis to the broadest possible audience and leave any interpretation of the works to the reader,” she told Times reporter Doreen Carvajal.

How times—and marketing strategies—have changed. Release of the movie The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, along with a changed religious atmosphere, has produced a deluge of “study guides” and “companions” to the simple story, together with new and reissued Lewis biographies and picture books, many now emphasizing Christian content. By the dozens, they have arrived from denominational publishing houses, para-church organizations, Christian houses, and religious divisions of commercial presses. “There are 45 to 50 books trying to ride the coattails of the movie opening,” said Lynn Garrett, religion editor of Publishers Weekly. “In sheer numbers, that is unmatched.” Some of the authors of these religious interpretations are from major universities or mainline Protestant seminaries. Others are drawn from the faculties of evangelical citadels like Wheaton College and Hope College, as well as from the world of Christian broadcasting.

Why this frantic competition? Is it simply spotting the main chance, the pursuit of lucre? There may be some crass opportunism—a less polite term for the market economy—but I think it is something more. It may be a battle for theological custody of Lewis’s legacy, an effort to use the movie’s release and the attendant hoopla as a tool for evangelism, or both. Sophisticated Christians, and those familiar with Lewis’s theological writings, Mere Christianity in particular, instantly recognize the redemption and resurrection motifs in The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe. But the unchurched and the non-Christians may not. For them it may simply be a charming tale, as much magical and mythological as religious. In order to reach these people, books like Finding God in the Land of Narnia and A Family Guide to Narnia: Biblical Truths in C. S. Lewis’s the Chronicles of Narnia are the modern equivalent of the neighborhood evangelist’s foot in the door. And if the first installment of The Chronicles is a box-office success, a cinematic franchise may emerge. After all, there are six more books in the original Chronicles of Narnia. More movies mean more books, which mean more opportunities for media-assisted soul-saving.

“Evangelicals are hanging on to Lewis as one of their own for dear life,” Garrett said. “It’s not just a marketing ploy; it’s a signal for them that they are in the mainstream.”

Martin Marty, emeritus professor of religious history at the University of Chicago, agreed. “I consider the evangelicals’ openness to Lewis’s sacred-and-secular to be a positive,” he said. “There’s no mischief there, and if they erode the line between commerce and faith, so does everybody.”

Phyllis Tickle, the author of numerous books on Christian spirituality, and former religion editor for Publishers Weekly, observed: “For evangelicals, Narnia as a highly successful film event offers significant mission opportunities. Lewis and his work come bearing gifts, including the cachet of enormous intellectual credibility, high critical regard and unquestioned academic standing. In other words, they introduce into the general conversation an evangelicalism that cannot be either scorned or scoffed at very easily.”

“In a culture presently inclined to scoffing and scorning,” she continued, “Narnia and its success provide a sweet opportunity to rise to a point of honor without being overtly belligerent or aggressive. By inundating the faithful—and the not-so-faithful, for that matter—with a clear message of its construction as an extended parable, or metaphorical presentation of the Christ story, such books rescue the casual reader from too secular a read. They also enrich the already informed reader with greater detail and the basis for richer appreciation. The publishing houses we’re talking about wouldn’t be ‘evangelical’ if they did not feel the genuine thrust toward spreading the Word at every opportunity—and this is one blockbuster of an opportunity. It would be almost irresponsible to not do a Narnia book, from that point of view.”

But some are not so sanguine. “Unfortunately, Lewis is being kidnapped by the evangelical right with stunning visual effects and a sophisticated marketing campaign,” said the Rev. Clair McPherson, of Trinity Episcopal Church on Wall Street. “He was not a fundamentalist or an apocalyptic; in fact Lewis was a moderate and a deep thinker who was always struggling with his faith. . . . Lewis was more concerned with an individual’s personal transformation and development within the Christian context, not some grand battle between good and evil.”

The millions who flocked to special, church-sponsored screenings the day before the general release—Rick Warren’s Southern California mega-church booked 13 screens for its 20,000 members—and to theaters in the days that have followed should not be disappointed. From the acting to the incredible, computer-generated special effects, there is plenty of inspiration. And if there is little explicit preaching, there is still plenty to fuel the sermon series and Sunday school sessions.

The lion Aslan, the Christ figure, says, “It is finished,” but not at the moment of his death. When he does die, the stone table on which he is sacrificed cracks, a clear reference to the rending of the Temple curtain in the New Testament. Dead characters are restored to life; whether this is simply relief from suspended animation, or resurrection, is left to viewers. As is the larger question, whether Christianity is Narnia’s “deeper magic.” Despite his recently revealed misgivings about a film version, I think C. S. Lewis would agree that this is a faithful—and useful—adaptation.

Mark I. Pinsky, religion writer for The Orlando Sentinel, is author of The Gospel According to The Simpsons and The Gospel According to Disney. His latest book, A Jew Among the Evangelicals, will be published this year.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.