In Review

Young Evangelicals Rock

By Amy Sullivan

The 1970s and early 1980s were good times to be a young Jesus geek. Christians may have endured periods of persecution and ridicule from ancient times through the Scopes Trial and beyond. But in the suburban evangelical church where I grew up, being Christian was not just expected—it was actually cool.

VeggieTales hadn’t been created yet, but we had Psalty, the anthropomorphic singing praise-songbook. We read Spire comics, a Christian offshoot of the secular Archie series, in which Archie, Jughead, and the whole Riverdale gang go on mission trips and talk about the Beatitudes. We grew our hair long, not to copy Marcia Brady but Amy Grant. And we strutted down our public school hallways in T-shirts from the latest Michael W. Smith or DC Talk concert.

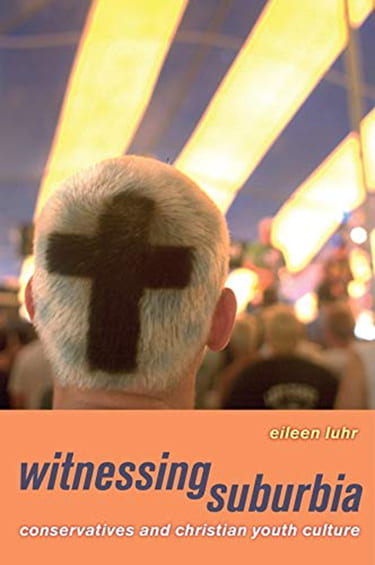

My youth group friends and I didn’t realize it at the time, but we were part of the first wave of evangelicals to consume Christianity as a brand in addition to a religious and theological tradition. It was the moment when Christian popular culture took off, and a new Christian identity—of pride, not persecution—formed. The era is at the heart of Eileen Luhr’s recent book, Witnessing Suburbia, a fascinating look at the emergence of Christianity™ and the development of Christian popular youth culture.

The story Luhr tells about the growth of Christianity into a global marketing force is unfamiliar for the simple reason that it took place at the same time as the more controversial rise of the Religious Right. The bombastic Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson commanded media attention, whereas the enterprising pastors who founded megachurches and changed the face of evangelical worship went largely unnoticed. Book burners and lyric banners generated debate; Christian music producers and concert promoters generated profits but little notoriety.

Witnessing Suburbia

And yet without the background and context that Luhr, a history professor at California State University, Long Beach, sketches in detail, it is nearly impossible to understand the current American evangelical community and the seismic changes that may reshape it for a new generation.

As evangelicals moved into the latter half of the twentieth century, many remained in a self-imposed exile, intent on following the biblical injunction to be “in the world but not of it.” This meant abstaining from temptations and corrupting influences, including secular popular culture. These conservative Christians had begun to develop their own parallel institutions, including entertainment outlets, but the offerings were largely limited to programs such as “The Radio Revival Hour” or “The Family Bible Hour.”

The separatist impulse held firm into the 1960s when it ran into the youth revolution. In the face of changing cultural mores and newly popular music forms like rock and roll, evangelicals were divided. One camp responded by condemning popular culture and seeking to limit its influence. But the other, sensing an opportunity to keep young evangelicals engaged, sought to appropriate the culture for Christian themes and purposes. The two conflicting approaches—let’s call them separatist evangelicals and engagement evangelicals—vied for several decades, and the ultimate triumph of one over the other directly explains the vibrancy of American evangelicalism today.

The first group of evangelicals, Luhr argues, was driven by two main beliefs about youth and culture. “Beginning in the late 1970s,” she writes, “youth came to be viewed as endangered, rather than dangerous. While the paradigmatic youth of the 1960s was a young hippie or student protester, that of the 1980s was a younger, innocent white child capable of devout belief but in need of parental guidance and protection.” This conviction that teenagers and young adults were not themselves threats to Christian morality, but were instead passive victims of a dangerous culture, allowed the separatist evangelicals to focus on battling popular culture, not their own children.

The emphasis on protecting children also enabled separatist evangelicals to mainstream their efforts by speaking as parents, not just as theological conservatives. As Luhr notes, a variety of organizations such as the Parents’ Music Resource Center, Mothers Against Drunk Driving, and the National Federation of Parents for Drug-Free Youth were all formed around the same time and also promoted the idea that America’s youth were imperiled innocents.

At the same time, separatist evangelicals were convinced that the problem with popular culture was not just the content or message, but the medium itself, particularly rock music. Luhr quotes a music professor at the fundamentalist Bob Jones University who, in 1971, made the case that rock was inherently dangerous, attracting—among others—”drug addicts, revolutionaries, rioters, Satan worshippers, drop-outs, draft-dodgers, homosexuals and other sex deviates, rebels, juvenile criminals, Black Panthers and white panthers, motorcycle gangs . . . and on and on the list could go almost indefinitely.”

The university’s president, Bob Jones III, trained his fire on other aspects of the counterculture that he viewed as incompatible with a Christian lifestyle. Jones criticized the Jesus Movement, the most visible Christian youth movement at the time, because it allowed converts to retain their hippie dress and embraced more modern worship styles. Sounding for all the world like a stock character from the movie Footloose, Jones wrote: “Revival is not spawned in pot parties, love-ins, hippie pads, dens of iniquity, and rock orgies; but that is where the Jesus Movement was spawned.”

Not even seemingly innocuous secular entertainment for children was safe from judgment. Decades before Jerry Falwell denounced Teletubbies for supposedly including a secretly gay character, anti-rock critics like David Noebel went after a series of children’s folk recordings that had been endorsed by such upstanding outlets as Good Housekeeping and Parents Magazine for promoting radical political messages by communist folk singers. Noebel and others reserved a special contempt for Bob Dylan and his leftie sympathies—until the musician became a born-again Christian during the 1970s and recorded several Christian albums. (Once Dylan returned to Judaism a decade later, he became fair game again.)

The goal of separatist evangelicals was to limit the exposure of children—and, occasionally, all citizens—to objectionable pop culture. Activists affiliated with Parents Against Subliminal Seduction (PASS) successfully lobbied for a San Antonio ordinance that restricted attendance at “obscene” rock concerts to those above the age of 14. In 1983, Ronald Reagan’s evangelical secretary of the interior, James Watt, banned rock acts from the annual Fourth of July celebration on the National Mall. The previous year, concert performers had included such subversive acts as Wayne Newton and the Beach Boys.

While some evangelicals worried about satanic subliminal messages in rock songs, others were adapting cultural forms for their own purposes.

While separatist evangelicals were busy bashing folk musicians or wringing their hands about possible satanic subliminal messages in rock songs, another group of evangelicals was more interested in adapting cultural forms for their own purposes instead of condemning popular culture outright. These engagement evangelicals drew inspiration from the theologian Frances Schaeffer, who urged them to compete in the “marketplace of ideas” rather than the “hidden censorship” of separatism.

In the aftermath of the 1960s, Luhr writes, “these evangelicals sought to fit within, rather than react to, suburban consumer culture.” Like their secular peers, young evangelicals thought in terms of rebellion against the larger culture. But, for them, the maverick path involved proudly proclaiming their Christian identity at a time when many believed the United States was becoming a post-religious society. These evangelicals reclaimed rock music for themselves by identifying its roots in gospel music. Elvis, they noted, came from a Pentecostal background, as did Jerry Lee Lewis and Johnny Cash, and their earliest musical influence was gospel. Young evangelicals saw that it was possible to embrace rock music while rejecting the content.

Separatist evangelicals argued that rock music destroyed the Christian message— one critic said that listening to Christian music was like “trying to get my meals from the garbage can”—but engagement evangelicals saw a way to appropriate the art form and even infuse popular culture with Christianity. “Proponents of Christian rock,” writes Luhr, “argued that the genre provided a tool for evangelism and a way for believers to enjoy contemporary entertainment while enhancing their faith.”

Christian music really took off in the 1980s, aided by the fact that rock music had become so commercial that it was no longer easily associated with rebellion. In 1984, Christian artists sold 20 million albums, and the next year they outsold jazz and classical music combined. Christian radio stations expanded across the country, providing platforms for artists ranging from Sandi Patty to the metal band Stryper, while also promoting themselves as outlets for “family-friendly listening.” Some evangelicals even started looking for ways to sanction acceptable secular music for their children. One article for Christian parents argued that parents who played their kids’ records backwards in search of evil messages were missing a valuable opportunity to engage productively with youth culture. “Believers should scrutinize secular music for Christian—not satanic—content,” wrote the author. “Should Madonna’s repulsive ideals and behavior invalidate the profoundly anti-abortion message of ‘Papa Don’t Preach’? Do Janet Jackson’s recent sleazy videos make her bold song urging sexual restraint, ‘Let’s Wait Awhile,’ any less true? We think not.”

And while music was the most visible part of Christian popular culture, other merchandise—including clothing, toys, and books—was aggressively developed for and marketed to evangelical Christians as well. Luhr notes that Christian bookstores “cater[ed] to a growing evangelical population that believed Christianity was a lifestyle as well as a belief system.” Between 1965 and 1975, Christian bookstores grew from 725 nationwide to 1,850, and in 2000 alone, Christian merchandise produced $4 billion in sales. (The advent of online shopping has shuttered many independent Christian bookstores, as has the sale of books from evangelical authors like Rick Warren and Tim LaHaye through Wal-Mart and other mainstream stores.)

Just as megachurch pastors have learned to co-opt elements of popular culture to spice up their worship services—weaving clips from Saturday Night Live into multimedia sermons or rewriting the lyrics of popular songs to tell Bible stories—Christian songwriters have adapted every conceivable musical genre, from pop to rap to punk to metal. For the more popular artists, a tension sometimes exists between them and their fans, many of whom fear that the bands will be tempted to water down their messages in an attempt to break into secular markets. Yet it is through that cross-over that Christianity has gained a foothold in popular culture. In summer 2008, the Southern rock band Third Day became the first Christian act to land on the cover of Billboard magazine. That same year, millions of Americans listened at home as the contestants on American Idol sang “Shout to the Lord” for a special fund-raising episode.

Christian culture has undoubtedly provided a way to make the Good News palatable for secular listeners. But its booming popularity is due in large part to the fact that it allows—and in fact encourages—evangelicals to focus on themselves.

Outdoor music festivals have become perhaps the most popular way for young Christians to pursue that goal of affirming their religious identities. Dozens of gatherings take place around the country every summer, each featuring lineups of Christian artists and drawing tens of thousands of young Christians. Importantly, they are not revivals—altar calls may be issued for those who feel moved to become Christians, but events like Cornerstone or the Sonshine Festival are more about giving existing Christians a place to socialize and worship together.

They have also, I discovered a few summers ago while covering Creation Fest in central Washington State, become a magnet for conservative political causes. The subtitle of Luhr’s book is “Conservatives and Christian Youth Culture,” and she writes about the conservative tilt and influence of suburbs in the postwar era in her exploration of Christian culture. But, in truth, there’s nothing inherently conservative about Christian pop culture. As a child I spent hours at Logos (“The Word”) bookstore just off the campus of the University of Michigan and the flagship location for a chain of more than two dozen Christian bookstores with a theological, not political, mission.

I arrived at Creation Fest hoping to revel in the same Christian culture I’d grown up with, maybe picking up some Moses Bobblehead dolls or Samson action figures at the same time. But when I scouted out the vendor tents, I was surprised to find that the Christian kitsch was swamped by booths for conservative causes. The first stand I came to featured a petition to sign supporting the people of South Dakota in their efforts to ban abortion. Next to it was a book with photos of abortions, a handmade sign warning that it should only be viewed by those “13 and up.” Available for sale were T-shirts bearing slogans like “Abortion Is Selfish” and “There’s nothing intellectual about believing you and I evolved from hydrogen gas.”

Yet as I walked the grounds of the festival, I saw very few teenagers wearing political shirts. (The most popular T-shirt read, “Hug Me If You Love Jesus.”) Nor were the people I spoke with preoccupied with banning gay marriage or protecting prayer in schools. Crystal, a student at Ecola Bible College, talked about wanting to go to Africa when she graduated. She had seen a movie about boys in Uganda who were abducted and forced into a rebel army, and she wanted to help them. If she saved some souls along the way, that was a bonus, but Crystal was more concerned about their physical safety. Even one T-shirt vendor told me he wanted to add some shirts with pro-environment messages to his inventory. “It’s really ignorant and arrogant not to take care of God’s creation, this gift we have,” he said, while behind him boxes of anti-evolution wear overflowed.

The bands at Creation Fest were perhaps most vocal about acting on their faith to help others. Members of The Myriad talked about traveling to Haiti when the tour ended and their plans to build an orphanage there. “It would be fantastic,” lead singer Jeremy Edwardson said, “to get socially involved and inspire audiences to care as well.” It was hard not to wonder whether conservative political causes have become associated with Christian pop culture by default, because conservatives have shown up and engaged with the culture and liberals have not.

Witnessing Suburbia is an invaluable read for those wondering how a religious tradition that once shied away from dancing and card-playing embraced electric guitars in the sanctuary and video games about the Rapture. And because Luhr is a historian, it is most useful in understanding how American evangelicalism became the version we know today. As evangelicalism continues to evolve, we will need to wait 20 years for a look back at the role Christian pop culture is playing today.

Amy Sullivan, MTS ’99, is a senior editor at Time magazine. Her first book, The Party Faithful: How and Why Democrats Are Closing the God Gap, was published by Scribner in 2008.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.