Dialogue

Will Religious Progressives and Nones Forge Political Alliances?

The religiously unaffiliated might be the most consequential portion of America’s rapidly changing religious and political landscape.

By Quardricos Driskell

I LOST MY RELIGION when I became a pastor of a church.

By this, I mean some of the traditions and dogmas of Christianity fatigue me.1

As the saying goes, I was raised in the church. That is, my mother and maternal grandmother were engaged at the level where we found ourselves in and around church often. I did not understand this until I was older, but going to church for us was partly cultural. As African Americans in the post–civil rights era, and Southern, it was a part of our cultural tradition to attend church.

While my upbringing inspired me to consider ministry as a vocation, I often find certain conventions of my tradition, at least its more conservative and evangelical perspectives, to be constraining to my theological beliefs and my natural modes of expression. The call to traditional Christian ministry came at an uncertain time for me, when I least expected it and did not really want to embrace it.

I fancy myself a traditionalist who does not believe in traditionalism—in the sense that I believe in institutions, but I am not resistant to change. Change is often viewed as a negative when it comes to matters of the church. In my preaching, I quote Beyoncé and Tupac lyrics along with scripture. I quote the Buddha or the wisdom of Ganesh. At times, I use expletives to emphasize certain points. I openly discuss my love for good red wine and whiskey. I express my exasperation with dating and, while I usually wear my comfortable Oxford dress shoes, on occasion, I sport my Vans with colorful socks. I prefer to adorn myself with a flamboyant bow tie and more than one pocket square in my suit-jacket pocket.

In short, I am a millennial.2 I am a reluctant pastor who still wrestles with God about “the call.”3

It is a strange position to find myself in—leading a historic, predominately African American Baptist church that came out of a school started for freed enslaved people in 1863. I sum up my being a pastor as God having a keen sense of humor.

Why Christian? Why Baptist? Why a minister of the Gospel of Jesus Christ? I struggle with these questions quite often, and the answers have varied over time. Yet I have been compelled to proclaim a reluctant “yes” to the Eternal God through faith and with vocational commitment. The primary purpose of church, in my experience, is to be a meeting place where those who seek freedom through God personified in Jesus Christ worship together and listen to the sacred text proclaimed.

By going to church, I learned, in a peculiar way, that humankind is placed at the tumultuous intersection of natural and human history, with daunting responsibilities to each. Therefore, I decided to stick with the religious tradition of my childhood, born as I was to a people who endured historical and systemic traumas, but who looked up into the sky and knew they were beloved.

Of course, the unfortunate reality is that humankind as a whole has yet to learn how to take care of the earth and of one another. Despite our technological and scientific advancements, despite our ever-increasing knowledge base, social ills still abound in ways that cause us—they certainly cause me—to question the supposed evolution of civilizations, especially since these social ills are alive and well in the developed world.

We live in a nation where it is still controversial to proclaim that Black Lives Matter, that women’s rights are human rights, that climate change is real and that LGBTQIP people deserve civil liberties. Clearly, we still have a ways to go! And while “the church”4 remains an active social and civic agent in U.S. society, quite simply it no longer occupies the same public position it did for previous generations. Moreover, for some young people with (and without) faith, it is in social movements for black and brown people, women, LGBTQIP people, and climate justice that they have begun to find hope again.

Though I have focused so far on my vocation in pastoral ministry, politics (and public policy) is my first love. And currently, I am party-less, a former moderate-to-liberal Republican who, since President Obama, believes the Republican Party has become more of a rural, white pseudo-religious party anchored far away from the needs and concerns of the commonweal of our country. As a millennial politico, I find myself thinking a lot about what the shifting religious landscape in the United States will mean for our also shifting political landscape. I am particularly interested in the “religiously unaffiliated” and how they might bring some creative novelty to politics.

ACCORDING TO THE Pew Research Center Forum on Religion and Public Life, young people between the ages of 18 to 29 are significantly less religious than previous generations of Americans. One-third of millennials between the ages of 18 and 35 identify as “none of the above.” When asked what religious tradition they belong to, they check the box “unaffiliated.”5

In General Social Survey data released in 2018 and analyzed by Ryan P. Burge of Eastern Illinois University, the religiously unaffiliated are the fastest-growing group in the United States, now on par with other religious “blocs”:

Americans claiming “no religion”—sometimes referred to as “nones” because of how they answer the question “what is your religious tradition?”—now represent about 23.1 percent of the population, up from 21.6 percent in 2016. People claiming evangelicalism, by contrast, now represent 22.5 percent of Americans, a slight dip from 23.9 percent in 2016.

That makes the two groups statistically tied with Catholics (23 percent) as the largest religious—or nonreligious—groupings in the country.6

The Pew Research Center recently asked a representative sample of more than 1,300 of these “Nones” why they choose not to identify with a religion. Out of several options included in the survey, the most common reason given was that they question many religious teachings (25 percent). Another 21 percent said they disliked the positions churches take on social and political issues, and 28 percent said none of the reasons offered are very important.7

If I were not an evangelical, born-again, theologically and religiously universal, ecumenical liberal progressive humanist American Baptist and Progressive National Baptist Christian minister, I probably would check the unaffiliated box, too. By saying this, I am not trying to be provocative; neither am I arguing for self-consistency. Rather, I make a point of embracing all aspects of my religious identity, because that leads me to embrace other faith traditions as well as the Nones.

Religious Nones or the religiously unaffiliated are by no means a monolithic group. They tend to be categorized into three broad subgroups: self-identified atheists; those who call themselves agnostic; and people who describe their religion as “nothing in particular.” But the numbers and categories only tell half of the story, since at least two-thirds of Nones say they believe in a higher power.8 (Some call this higher power “God”; others call it “Love” or “Community”). Simply because they do not religiously identify doesn’t mean they are not religious or spiritual.

What is true of many young people in this group is that they feel religious institutions have left them behind. Alternatively, religious institutions have not sought to include them, or have shunned them, and consequently they have left the institutions behind. This has led some to feel disconnected from the foundational structures that have traditionally held communities together. I, too, feel disconnected from the religious institution that shaped my being, but I am not a None, precisely because I choose to identify with multiple labels. I suspect that many who check the unaffiliated box identify in multiple ways, too.

To understand the millennial religiously unaffiliated trend, you have to understand the context. Millennials came of age in an era defined by truthiness—one in which social and political pundits replaced priests and professors as arbiters of truth. They grew up in an age of hypercommunication and hypermaterialistic cultural cues that defined life in the social empire of the United States. Social media mediates a sense of belonging and togetherness that makes them feel—or appear to feel—connected to their neighbors and their community. This is largely a generation of young people who believe that ethical ontological beings should show up in every way possible. They are also a generation that realizes grace could be an aspirational philosophical concept, where there is no heaven or hell but what we make here on earth.

If you can build a heaven for yourself and others,9 you can also build a hell for yourself and others. The reach and consequences of your decisions are limited only by your ability to act—i.e., your power. Thus, what Nones want is agency and meaningful community. Perhaps some are reacting to the limitations of certain specific persuasions of evangelical theology and praxis to address their cultural and social circumstances. However, most are not interested in dismantling the church or traditional institutions, but they long for systems and institutions that bring people together around impactful meaning, often—though not always—with a social justice lens.

Social justice to some Nones is seen as a universal good, even as they refuse to collapse that goodness into any tradition that says “good” is determined by a deity. This is where my own theology calls for solidarity with the Nones. I am not, per se, interested in drawing the nothing in particulars or the religiously unaffiliated10 back to the church—especially given the contemporary circumstances that exemplify a failure of many churches to offer a better theology and more insightful praxis vis-à-vis both pastoral care and public ministry. Instead, I choose to stand in solidarity with Nones with the aim of using existing religious and political institutions to benefit society holistically. After all, even those of us with religious commitments who actively pursue social justice are less concerned with the origin of “good” and more focused on the bilateral relationships among people that create social justice on the ground, and on how they can be made more resilient and enduring for the ages.

I’ve come to understand that these nothing in particulars or religiously unaffiliated might be the most consequential portion of America’s rapidly changing religious and political landscape. Yet many do not associate the Nones more broadly with politics, and so far, no major party or caucus has expressly acknowledged the importance of the nonreligious sector. There are reasons for this. Though nonreligious people make up one-quarter of the population, in the 2018 election they cast only 17 percent of the votes. By contrast, polls show that white evangelicals—the most consistent right-leaning conservative voting bloc—include less than 15 percent of the voting population, yet they have cast 26 percent of the votes since 2012 (keep in mind that only 10 percent under 30 years of age identify as evangelicals, so the future points to decreasing influence from this group).11

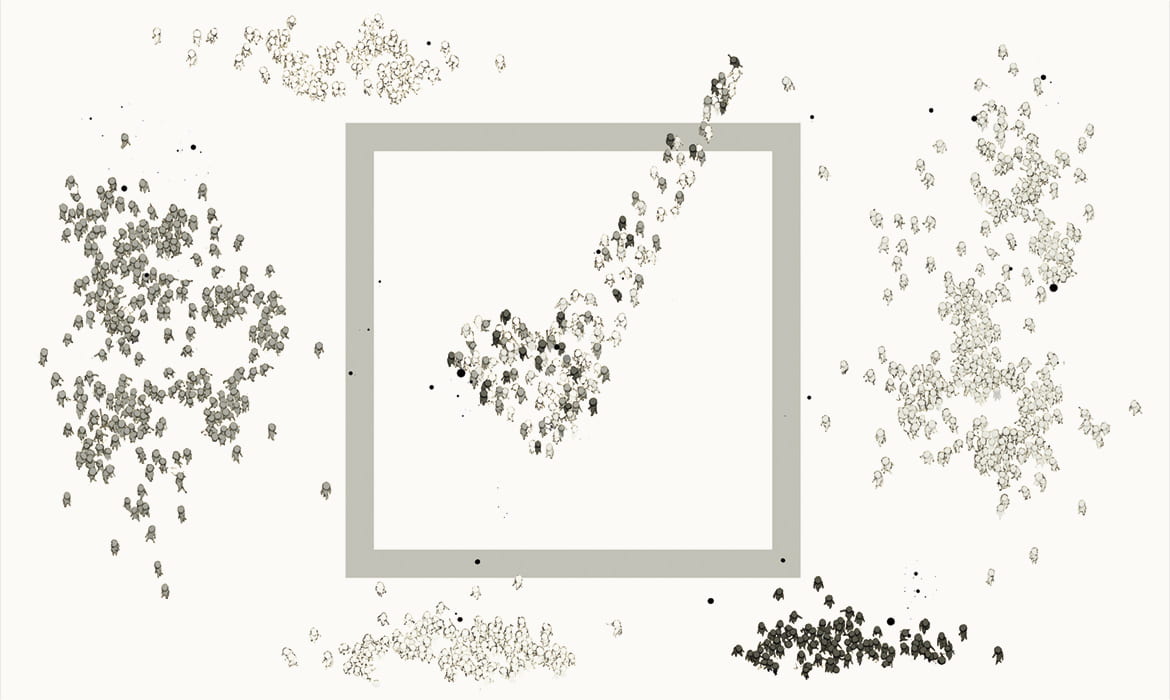

The Nones have so far not organized as a group, and the smaller humanist and free-thought organizations do not have the funding to do the kind of electioneering that some religiously based organizations are able to provide. As James A. Haught puts it in a special issue of Free Inquiry magazine, “The Nones and the Vote”: “It isn’t easy to corral Nones, because they aren’t gathered in well-marked congregations like white evangelicals are. They’re free spirits, scattered almost invisibly through society.”12

It is perhaps never going to be as easy to reach and organize the religiously unaffiliated as it is to do so with white evangelicals, black Protestants, or other more traditional religious groups. However, if Nones were to organize, they could have enormous impact. Polls indicate that this demographic is liberal, urban, and more educated than the average population, and surpasses most other single religious voting blocs in the United States by these measures. A significant majority of Nones support LGBTQIP rights and abortion rights for women (close to three-quarters on both counts, and when you include atheists and agnostics, these percentages go up even higher). Nones tend to vote reliably Democratic, though some are registered as independents or Republicans, and many are unregistered.

So, how will this group of secularists, humanists, and religiously unaffiliated further find their voice and activism in the 2020 election and after? And what should religious progressives and political parties do to help this group participate more actively in American political life?

There are some signs that this growing group might be starting to organize as a political bloc. Haught points to a couple of examples coming from “secular values” organizations:

The Secular Coalition for America operates Secular Values Voter, publicizing the rising power of the irreligious. Similarly, other groups support Secular America Votes, which declares: “Showing politicians that atheists, agnostics, freethinkers and other secular people are a powerful (and growing) voting bloc requires getting out the vote and demonstrating that we are a force to be reckoned with at election time.”13

To respond to this burgeoning demographic, in April 2018 four members of Congress established the Congressional Freethought Caucus, designed to, among other goals, oppose “discrimination against atheists, agnostics, humanists, seekers, religious and nonreligious persons” and to champion the value of freedom of thought and conscience worldwide.14

Another important question is whether Democrats will improve their religious outreach after 2016. It is no coincidence that Democrats hold a large margin among black Protestants, white liberal Protestants, LGBTQIP religious individuals, Jews, Hindus, Muslims, and the religiously unaffiliated. However, in the past, Democrats have rarely talked about religion. Will the revival of the religious left or of religious progressives lead to political organizing around key issues, and will the Nones join with these religious progressives to counterbalance the familiar Religious Right that turns out to vote reliably Republican?

As we get full swing into the 2020 election season, we see Democrats uttering religion more than usual. Hopes that the Democrats might appeal to voters using religious rhetoric have centered on one newcomer in particular, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, an outspoken gay Episcopalian who has called out the hypocrisy of Trump’s policies and his unwavering enthusiasm among largely white evangelical Christians. Even in my home state of Georgia, Sarah Riggs Amico, a Democratic candidate for the U.S. Senate, running to oppose incumbent Republican David Perdue, launched her campaign in August with a video that made a direct appeal to religious voters in the state.

It is also worth noting that Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii, a combat veteran and foreign policy expert, is the first Hindu candidate to run for president of the United States. And Marianne Williamson has truly introduced spirituality into politics. Williamson’s made-in-America “transformational wisdom” involves personal growth and introspection, and she has brought terms like “dark psychic forces” into the conversation—concepts we have not seen on the political stage before. Her chief innovation is a proposed cabinet-level Department of Peace for “promoting life instead of death.” Though Williamson’s chances of winning the Democratic nomination are slim, could her presence and new-age spiritual language help engage Nones and galvanize them to turn out in 2020?

BY MOST PEOPLE’S account, our political system and our traditional religious institutions are in dire need of transformation.

Everyone agrees that mainline Christianity in the United States has been upended, and many lament the loss of this counterweight to white nationalist or far-right Christianity, but too few people are focused on the spaces and places where this transformation, or “spiritual innovation,” is happening. I define “spiritual innovation” as reaching beyond traditional methods of religion and spirituality, through practices and efforts that bridge, impact, and inspire people. Sometimes this happens inside the political realm, and sometimes outside of it. In my view, calling for innovation does not necessarily mean abandoning faith or exclusively being nonreligious; it means creating spaces and challenging traditional notions of religion and spirituality in ways that lead to socially transformative conversations and political action. These efforts need to engage both the religious and nonreligious, taking what is dying, traditional, or historic and either using it or transforming it to form new life.

What does transformation—spiritual innovation—look like? It looks like The Sanctuaries, an art space community in Washington, DC, that is multiracial and multireligious and uses poetry, music, and the arts as a way to advocate for social and political causes and to build what they call “soulful community.” And sometimes it looks like New City Church in Minneapolis, whose ministry is centered on environmental justice, so much so that the worship service is held outside in nature. Or it looks like Sisters & Seekers, an organization with a dozen gatherings across the country affiliated with Nuns & Nones, a growing alliance connecting Catholic religious women, most of whom are over 60, with 20- and 30-something millennials, many of whom are Nones. Or sometimes it looks like traditional institutions with a new spin, like Impact Church in Atlanta, an inclusive gathering of people committed to Christian ecumenism.

Unfortunately, some well-respected Christian leaders teach that the church should abandon politics altogether. These leaders fail to realize something I discovered at an early age in Atlanta—that religion is always political, but never partisan. I believe that each of our beliefs is deeply rooted in a much broader and more complex political ideology. Climate crisis denial, for instance, is now inextricably linked to beliefs in unfettered capitalism, and in “prosperity theology,” the belief that material gain is a reward by God for personal virtue. Instinctively, and sometimes in a deeply informed way, many who see this as the essence of Christian “religion” pull away, choosing not to affiliate.

Liberals do not want conservative Christians to bring their conservative values to the ballot box or their biblical ideas to the centers of power in our government. Yet liberal and progressive Christians desperately need to look at what they stand to lose if they fail to engage as Christians in the political process. This is where I think those who identify as nothing in particular have a unique advantage, since there is more crossover between these groups than is often acknowledged. Formerly religious progressives make up the bulk of those who choose to call themselves “religiously unaffiliated.”

Walter G. Moss defines “religious progressivism” as “a means of progressivism motivated by values that have long been championed by the world’s major religions—love, wisdom, compassion, empathy, humility, patience, prudence, and self-discipline.”15 These religious progressives, or the “religious left,” are remnants of the populism and progressivism that occurred a century earlier, as Harvard historian Jill Lepore explains in These Truths: A History of the United States:

Populists believed that the system was broken; Progressives believed that the government could fix it. Conservatives, who happened to dominate the Supreme Court, didn’t believe that there was anything to fix but believed that, if there was, the market would fix it.16

While this is an oversimplification of nineteenth-century political ideologies, these basic characterizations still ring true in the twenty-first century. Lepore argues that the vitality of Progressivism grew out of Protestantism, especially out of the Social Gospel movement.17 Decades later, African American preachers, scholars, and activists, such as Benjamin E. Mays, Mordecai Johnson, Howard Thurman, Martin Luther King, Jr., and others, took the underpinnings of the Social Gospel movement and chided those churches that separated the secular realities of daily life from spiritual needs. Church, in King’s view, should not only be concerned with the spiritual but also with the secular. This led to the 1961 formation of the Progressive National Baptist Convention. This is the tradition and some of the beliefs that birthed my own theological formation.

It is time for those of us who are in this lineage of religious progressivism (knowingly or unknowingly) to join forces with the religiously unaffiliated, or with the Nones generally. How can the religious left speak to the so-called secular left more effectively? This will take listening, engaged conversations, and a willingness to work together, despite differences, to achieve the larger electoral and societal goal of a transformative society. It is incumbent upon those of us who are Christians to use welcoming language and to explain that our theology is an inclusive one. After all, if you look at Jesus’s life, he hung out among those who were shunned by religious institutions in his time—“harlots,” rough-hewn fishermen, eunuchs, lepers, and Samaritans. Dare I say that Jesus might be a religiously unaffiliated millennial if he was walking among us today?

I’d also like to see the congregations of the religious left do a better job of being the “church in society” from a progressive perspective—becoming a hub for rigorous, probing discussions of critical world and human conditions, open to all who care about these concerns whether they practice the faith or not. And we need to make our support for LGBTQIP rights more explicit and clear. Accepting homosexuality is something that most Nones support, and so do increasing numbers of younger white evangelicals.18

The fabric of the values America claims to stand for is presently under attack, and as the 2020 White House race draws closer, politicos, journalists, scholars, and historians interested in religion and politics should examine whether the religiously unaffiliated might impact, even if slightly, the election. The Republican Party has become more and more associated with “Christian values” and, in 2016, adopted in the party platform a series of statements of support for biblical morality and the rights of Christians to practice their beliefs.19 It is no wonder that when people say “Christian voters,” the younger generation tends to associate this with white people and conservatives. But many young people hunger for candidates who can speak about the values they hold dear, such as inclusion and justice, living a purposeful life, working toward environmental and economic sustainability, valuing experiences over material things, and nurturing authentic communities.

One thing I am sure of is that 2020 is not going to be a policy election. It is going to be a character and fundamental principles election, perhaps more so than any other election in most of our lifetimes. Nones have an important role to play in this election, and in our society, and it would be best for us all if we could move beyond generational and religious versus nonreligious schisms to find common ground around our shared values.

The rise of the Nones is also a rebirth resurging in the Democratic and progressive movements. As a recent Atlantic article puts it, “This generation-based party realignment has profound implications for the future of American politics.” But I do not believe this necessarily needs to lead to a “coming generation war,” as the Atlantic article is titled, given the many opportunities that exist for cross-generational alliances.20 Spiritual innovation happening on the ground reveals that millennials are open to drawing on the wisdom of traditions and elders in both spiritual and activist contexts, while they are forging new ways of expressing that wisdom.

The 2020 election is a chance to do things differently. We have an opportunity to chart a new course for spiritual and political life to address our profound challenges. If we can work together to improve public understanding of the place religion and reason can and should have in twenty-first-century politics, we do not have to be boxed in by the boxes we choose to check on survey forms.

Notes:

- This is not to be confused with the religious vs. spiritual debate, for I believe one needs religion—which usually entails adhering to a certain dogma or belief system—in order to be spiritual.

- This cohort includes younger millennials (the generation born between 1981 and 1996) and older members of Generation Z (born after 1996); Michael Dimock, “Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins,” Pew Research Center Fact Tank, January 17, 2019.

- One of the unique aspects of the religious profession is the high percentage of those who claim to be “called by God” to do the work of Christian ministry. This call is particularly important within African American Christian traditions.

- While I use “church” to mean Christian churches, I do not wish to exclude other houses of worship such as synagogues, temples, or mosques.

- Pew Research Center, Religion among the Millennials, Religion & Public Life (Pew Research Center, February 17, 2010).

- Jack Jenkins, “ ‘Nones’ Now as Big as Evangelicals, Catholics in the US,” Religions News Service, October 5, 2019.

- Michael Lipka, “A Closer Look at America’s Rapidly Growing Religious ‘Nones,’ ” Pew Research Center Fact Tank, May 13, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Apart, perhaps, from evangelical circles, this thought is neither theologically nor culturally novel to this time or generation.

- I use “nothing in particulars” and “religious unaffiliated” interchangeably: a specific subgroup of the Nones—those who may or may not be religious or spiritual but who do not claim a particular religion.

- Tara Isabella Burton, “The GOP Can’t Rely on White Evangelicals Forever,” Vox, November 7, 2018, cites statistics from the Public Religion Research Initiative.

- James A. Haught, “Prodding Nones to Vote,” in “The Nones and the Vote,” special issue, Free Inquiry 39, no. 4 (June/July 2019).

- Ibid.

- Julia Manchester, “Dem Lawmakers Launch ‘Freethought’ Congressional Caucus,” The Hill, April 30, 2018.

- Walter G. Moss, “The Case for Religious Progressivism,” History News Network, June 30, 2019.

- Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States (W.W. Norton, 2018), 365.

- The Social Gospel movement was adopted by almost all theological liberals—and by a large number of theological conservatives at the time, too—who argued: “Fighting inequality produced by industrialism was an obligation of Christians. Social Gospelers brought the zeal of abolitionism to the problem of industrialism”; Lepore, 365–66.

- According to the 2014 Pew Research Center’s Religious Landscape Study, for instance, 45 percent of millennial evangelicals support same-sex marriage (compared to 23 percent of previous generations), and 51 percent (versus 32 percent) believe society should accept homosexuality.

- The Republican Party Platform: “We pledge to defend the religious beliefs and rights of conscience of all Americans and to safeguard religious institutions against government control.” Using the word “God” in official party platforms isn’t a tradition inherited from the earliest days of the two parties, but illustrates a trend toward more explicit reference to religion in U.S. politics and by political candidates.

- Niall Ferguson and Eyck Freymann, “The Coming Generation War: The Democrats Are Rapidly Becoming the Party of the Young—and the Consequences Could Be Profound,” The Atlantic, May 6, 2019. The turmoil of the 1960s led to a generational break between young people (now baby boomers) and their elders, but the current landscape is different. Though boomers seem to be inching right politically, Gen Xers are inching left.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

This read shed light on a growing number of “traditionally CALLED” who responsibly embrace change as it emerges within the congregation,community and political arena. We embrace change by merging our traditional religious beliefs and varying cultural context to accept the role that “nones” play in driving politics/advocacy and community building. Historically, many movements,especially in the African American community, started in the Church. Organizing and mobilizing the force was very organic within that demographic because we truly understood the plight of those around us. I believe that working alongside those who have varying experiences will prove beneficial going forward. Additionally, I appreciate the author embracing his own non traditional ways of being. I often get the “double take” when I tell people that I am in Ministry,a Politico and have served in the Armed Forces; I don’t look the part! That’s the beauty of it all- PRAISE IS WHAT I DO or KNUCK IF YOU BUCK; depending on what day it is.