Featured

Two-Part Invention

Perhaps we need a bifocal perspective on our vocational lives.

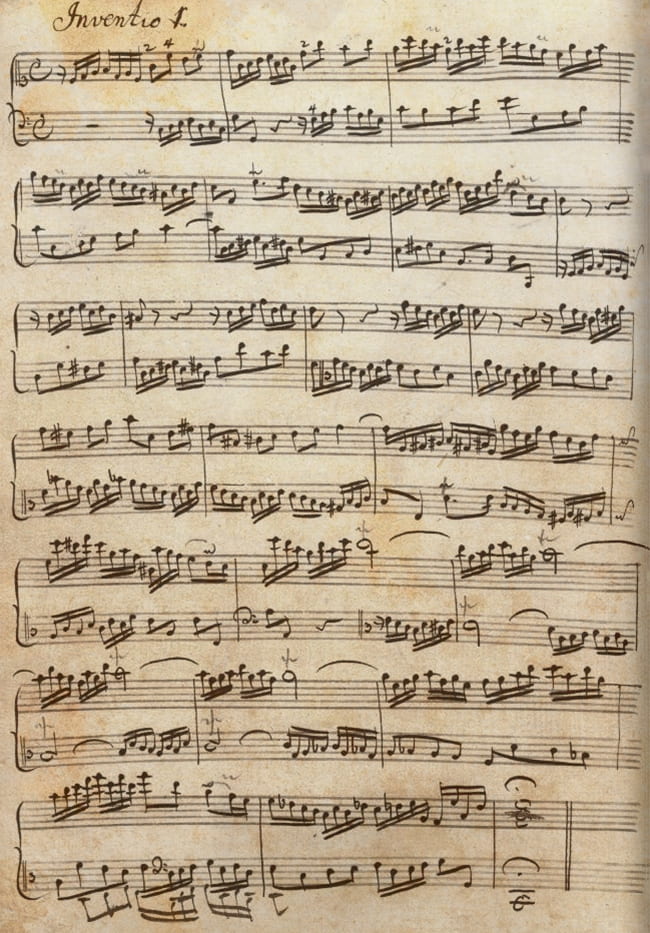

Inventio I manuscript, J. S. Bach. CC-PD

By Nancy J. Nordenson

I have invented a driver who stopped his car next to the cab in which I rode on the backed-up freeway entrance ramp and did a double take at the sight of the flute. He looked inside and saw a passenger, eyes closed, resting her head against the back seat’s top arc. Maybe it occurred to him that this was only a cabbie’s ploy for tips, but he turned off his radio, rolled down his window, and listened just the same.

I’ve invented this driver because I want a witness to the music. When I was a little girl, my parent’s Ford sedan had no radio. Stopped at a red light next to any car with music streaming out through an open window, my older brother and I would look at each other, smiling and laughing at our good fortune to snatch a taste of what lay beyond our own four doors. We imagined ourselves in a car that wasn’t ours, going who knows where, singing along to music and even snapping our fingers to the beat as we went.

We travelers are at the mercy of traffic, and Chicago traffic had stopped on the Foster Avenue entrance ramp to the Kennedy. Young and in college, I was headed home for a break. Next stop, O’Hare, could be fifteen minutes or an hour away. The memory of my cabbie’s appearance isn’t clear beyond his dark hair, clean shave, and olive complexion. He must have hoisted my suitcase into the trunk when he picked me up, a slate-blue hardcover Samsonite with light-blue satin lining. The suitcase had been my grandmother’s, then my mother’s, then mine, and it had been to places I had not. No doubt I’d sat on it, I always had to, my weight pushing the overstuffed sides to meet before the case would close and the two latches click shut. At that age I was smack in the middle of planning a life, hoping for a career, trying to figure out if I could indeed have it all, wondering and worrying about many things. I wanted to fly but instead was in a cab in a traffic jam with twelve hundred miles of airspace between departure and arrival. From the front seat came a flash of silver, and the driver lifted a flute to his mouth.

Into the traffic a space opened for the music to fill.

The plans, the rush, the plane up ahead vanished. In this cab were stillness and beauty. Around the driver, no piccolos or clarinets joined in, no trumpets or trombones, no conductor led the way. The man at his steering wheel played his flute for seconds or minutes until traffic began again to move, and he stopped and placed the flute back on the seat.

I asked him about his playing after we merged onto the northbound Kennedy. He said he did it for his customers.

They are stressed and anxious, he said, my music brings them peace.

I expect that the flute rolled into the seat’s crack where it waited within reach, in one piece, ready to play again. When traffic moves, there is no time to separate the parts and press them into a velvet-lined case; when traffic stops and it is time again to play, there is not a moment to waste reassembling. Alongside the flute would be his logbook where he records his miles and times, passengers and destinations. Maybe a grocery list, too, and a check waiting to be cashed.

To be sure, he picked up and played the flute later that day and the next, again and again, for there is no lack of traffic jams or anxiety on these streets.

♦♦♦

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “but do your work, and I shall know you.” So here is a question: the cab or the flute—which was the cabbie’s work?

On yellowed college-ruled paper, in bright blue ink and the kind of loop-de-loop handwriting that betrays an earnestness just short of maturity, are pages of notes I took long ago from a professor’s talk on career advice: “Nothing is for positive in life and thus any of these—money, prestige—may be lost overnight. . . . If one chooses a career in the context of a calling, so much worry is eliminated. . . . Your calling encompasses everything you are as a person. Use every part of yourself! . . . Study to explore the great infinite capacity which lies within yourself.” At that age, there were so many things that one could yet be, but driving a cab was a job I knew I’d never have. Give me a job with glass beakers, Bunsen burners, and petri dishes, a job of science that gets my hands dirty.

In the cracks between college biology and chemistry classes and labs, I took piano lessons from the music department for liberal arts credit. The practice rooms were off a single gray corridor in the basement of the music building. The sign-up sheet hung on a wall at the bottom of the stairs. I knew I didn’t belong there, even though the lessons granted me permission, and so I wrote my name in time slots when no one was looking, stealing an hour a day from those who were making music their livelihood.

My piano teacher assigned scales and selections from an assortment of music books. I remember Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words and Bach’s two-part Inventions. In high school, I had started to learn these inventions and was happy to revisit them. Each hand, left and right, seemed to have its own business, which suited me. Thrilled me even. The voice of the left hand did not bow to a single grand melody delivered by the voice of the right. Each hand played its part, which was a whole in itself, dipping and weaving and synced in time against the other hand’s part until both parts ended in a paced rush on a single, harmonizing beat.

I am paging through the old music book, its gold cover long gone, my teacher’s handwriting here and there, marking fingering or dates by which to finish. The introduction tells us that Johann Sebastian Bach had composed these tutorial-like pieces for his students so that, in his own translated words, they could be shown “a plain Method of learning not only to play clean in two Parts, but likewise in further Progress to manage three obbligato Parts well and correctly, and at the same time not merely how to get good Inventions [ideas], but also how to develop the same well.” Look at the scores and what you see in parallel tracts is a series of ascents—higher and higher—then descents before rising again. Mordents and reversed mordents could keep two or three fingers trilling forever if there was no need to keep time. To earn my final credit, I came up from the basement practice rooms for a recital. Washed and scrubbed from dissections, the Krebs cycle neatly memorized, Bunsen burner extinguished, qualitative and quantitative analyses of every sort accounted for in my blue-gridded laboratory notebook, I seated myself at a piano on a stage and played Mendelssohn’s “Agitation,” a six-page piece played presto agitato in the key of B-flat major.

Emerson also wrote, “Do your work, and you shall reinforce yourself.” Which work shall this be? Here is one work, and there alongside it or simultaneously just beyond it is another work. You pick something, and then you pick something else to put into that first something, and then you pick something else to put into that other something in a vocational mise en abyme, like one Russian doll nested inside the other. But the metaphor fails because there can be no predesigned, linear stacking.

♦♦♦

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost. A minister I know thinks that we should raise our voices in doxology—word or song—far more often than we do. As it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be. “Walk around all day humming it,” he said with a laugh, a challenge in his smiling eyes.

Poet and essayist Adam Zagajewski tells the story of being at a chamber music concert in the courtyard of a Tuscan palace that had once been a monastery. In response to a quartet’s playing of Mozart, the audience gave only sparse applause. Troubled at this inadequate response to the music, he launched a defense of ardor, winding through examinations of irony, intellectual poverty, and the loss of the sacred before landing on the concept of metaxu.

The word traces back to the Greek word “metaxy” in Plato’s Symposium and means one or more variations of “between.” The word links two disparate points: earth and heaven, seen and unseen, beginning and never-endingness, human and divine. Zagajewski suggests that perhaps those who could barely muster a clap when confronted with the music had difficulty moving in the space between quotidian and transcendent, point A to B—or B to A, depending on one’s starting perspective. Like looking through a pair of binoculars, the trick is to look boldly, one eye on the left and the other on the right, and see what you can see when the two vision fields overlap and the images merge.

Bifocal glimpses of reality come along all the time. Three-and-a-half hours into the flight of Apollo 8, astronauts Frank Borman and Jim Lovell—the first humans ever to be pulled into the gravitational field of a non-earth force—looked back at the view as their spacecraft hurtled up and away. “We see the earth now,” said Borman, “almost as a disk.” Through the window, the world registered in a glance. Lovell narrated a widescreen view of Florida and West Africa en route to the far side of the moon. Cape Canaveral in one eye and Gibraltar in the other.

World without end. This doxology ends with a roar through space, from starting note to no end in sight, like a train set in motion long ago that won’t be stopped. When my sons were little, I told them over and over, “I love you infinity.” Amen.

♦♦♦

My applied science education expanded to include needles and tubes and blood. Our white lab coats crisp and buttoned, my classmates and I sat one day in the laboratory at its black Formica counter. In front of us and standing upright in racks were tubes of our own blood that we had obtained while practicing venipuncture, the art of drawing blood, on each other. The boxes and boxes of glass microscope slides sealed in cellophane wrap suggested that here would be an extravagance of practice. Our instructor knew this would take awhile to get right.

Start with two slides on the counter: slide one receives the drop of blood; slide two spreads the blood across slide one’s surface. We were learning to make “peripheral blood smears,” which is a way to prepare blood so that it can be examined on a cellular level under a microscope. Machines can tell you a lot about the blood fed into them—for example, how many platelets it contains, the concentration of hemoglobin, the proportion of different kinds of white blood cells, and even the diameter of its average red blood cell—but only the human eye, trained and open, can both count cells and perceive subtle variations.

Place a drop of blood the size of a small garnet bead on slide one, centered and about half an inch from the end. Work fast. Press the narrow edge of slide two against the surface of slide one directly in front of the blood at about a 60-degree angle. Drag it backward until it has passed through almost the entire drop. The blood runs out along the edge in both directions, and just before it reaches across the slide’s full width, reduce slide two’s angle to about 45 degrees and pull the blood quickly across the length of slide one. The resulting smear looks like a feather if you did it right, dense toward the bottom and center and thinner along the edges with a feather’s characteristic wispy fringe along the top. Under a microscope, there in the fringe but not its edge, is where you’ll find cells presenting themselves for examination, single-layered and single file. Make another and another, finish the box, rip cellophane wrap, and finish that box too. Spend the supply. Memorizing facts can be rushed, but developing small motor skills, eye-hand coordination, and muscle memory takes time and practice.

Practice doesn’t stop there. Practice staining slides. Practice counting cells. Practice identifying normal and abnormal cells under the microscope. Practice words of taxonomy and description.

Writing this now, years after I last made a smear, I can still feel the movements in my hand. I pick up two index cards loaded with words and press and spread them one against the other, hoping for a fringe, and in my mind’s eye they are ready for the scope.

♦♦♦

I have recently read the most beautiful phrase: “a beholding that ascends.” The thing beheld is a bridge. Metaxu. The gaze draws you up.

Pavel Florensky, a late nineteenth-century Russian scientist and ordained Orthodox priest, wrote that phrase. Florensky’s dream was to be a monk, but rather than have him waste his scientific training, his bishop refused to give him the required blessing. Instead of a life of monastic contemplation, he reported for daily duty as head of research in a plastics plant and to university lecture halls where he taught physics and engineering wearing his cassock, cross, and priest’s cap while under the watchful eye of Kremlin authorities. Eventually, he ended up on a train to a Siberian gulag, where he died four years later, but not before he wrote those words—a beholding that ascends—and more about the experience of seeing Orthodox religious icons, mediators between earth and heaven.

Not long ago, I read advice by the unknown author of The Cloud of Unknowing: pick a word and hold it in your mind against the push of all words or impressions to the contrary. I like the idea of a word helping steer one’s course. Choosing ahead of time that this is what I’ll be about. I am practicing Behold as that word that steers me. Behold as a modus operandi, a way to witness, but more. In that gaze, to dwell, to linger. To hold. Open your hands and cup them together; receive what is given without dropping a crumb; pay attention and wait. Who can imagine all the places from which data come, pointing the eye to space beyond and back again? Julian of Norwich saw in a hazelnut all that was ever made.

I am placing blank index cards and a pad of paper alongside my work, in the cracks between journal articles on blood gone wrong, PowerPoint slides on hepatitis, and meeting notes on bone cancer. For seconds or minutes, I am stopping the words that are usually in my head during a workday—faster, harder, better, longer—and practicing writing about something other than disease. Practicing building bridges with words from seen to unseen and back again. Practicing seeing bridges already here. Practicing crossing the bridges found.

The experts say wholeheartedness is a key to fulfillment in work. Give yourself wholly, they urge. In a contrarian act of willful unwholeheartedness, I allow a fault line. To operate on one level here and another level there, is this not the same as a woman nursing one child while reading to another? Or perhaps this is wholeheartedness after all, but with a directional force that lies in another plane.

Call it a proof-of-concept trial, the endpoint being some measure of meaning, an invention yet to be and practiced even now. In the long line of progress from what is unknown to known, from a need unmet to met, this sort of trial is an early step. You prove one thing and it takes you to a next step you may or may not have predicted.

Next to my computer hangs a copy of Andrei Rublev’s Holy Trinity icon, which reflects the story of Abraham’s hospitality from Genesis. Three figures are seated at a round table. Two of the figures are robed in brilliant blue, and the third in gold. They are seated at the nine, twelve, and three o’clock positions. On the table is a gold chalice. You look at the icon, see it, and the image with the table’s open space at the six o’clock position invites you to step up to the scene and take a seat.

♦♦♦

The morning is new and I am reading from the Old Testament, my eyes moving left to right across the lines, top to bottom down the page, covering one word after another with their gaze, and here now is a chapter break. My thoughts meet the page at the white space, and I realize that my mind and my eyes had split almost from the start, my mind focused as it is so often on work and the tasks of yesterday and what will come today.

I am retracing the visual path, right to left, bottom to top, and beginning again. Behold. There is Elijah at the widow’s home; the jar of flour that was not used up and the jug of oil that did not run dry; the widow’s son ill and not breathing; Elijah with the boy in his arms, crying out to the Lord; Elijah stretched out on the boy, flesh on flesh. And now, the boy without breath breathes. He lives. This drama of life and love had been before my eyes without even the pause due a beautiful peach.

With brain busy and eyes dazed, what else have I missed?

May the Lord make him to live was Elijah’s prayer and, likewise, I pray for myself.

Nancy Nordenson is a medical writer and a creative writer. Her work has appeared in Indiana Review, Comment, Under the Sun, and other publications and anthologies, including Becoming: What Makes a Woman (University of Nebraska Gender Studies). Her work has also earned multiple “notable” recognitions in the Best American Essays and Best Spiritual Writing anthologies and Pushcart Prize nominations. Her book, Finding Livelihood: A Progress of Work and Vocation, will be published by Kalos Press in 2015.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.