Perspective

Trauma, Friendship, and Awakened Possibilities

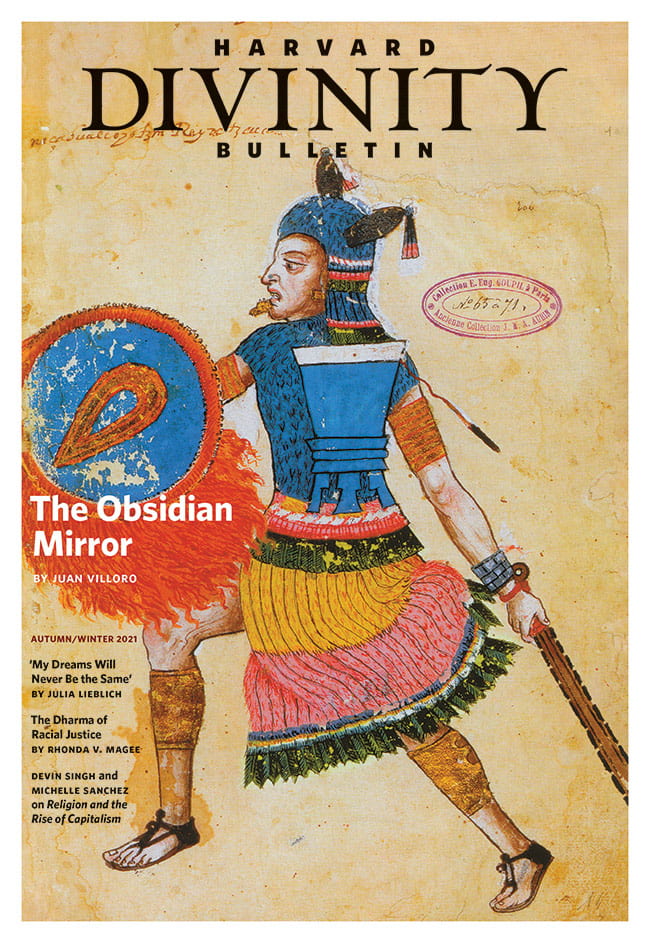

Cover illustration: Nezahualcoyotl (Fasting Coyote), from the Codex Ixtlilxochitl (1582), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Wendy McDowell

The first time I ever felt transported and transformed by reading a poem, I was 10 or 11 and came across Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est.” Owen’s “gas poem” from the First World War conveys the sensually overwhelming, surreal nightmare of watching a fellow soldier “guttering, choking, drowning” as he dies.1 The psychic position of the poem is with the other soldiers trudging behind “the wagon that we flung him in.” The imagery is appropriately grotesque (“the white eyes writhing in his face,” “the blood / Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs”), and it does not allow the reader to look away or find consolation. The speaker prods us to consider our collective responsibility for the atrocities of war and entreats us to stop romanticizing such senseless slaughter.2

I could picture the dying soldier in the wagon—and his witnesses—as my relatives. Two of my father’s older brothers served in the Korean War, one of his youngest brothers served in Vietnam, and one of his brothers-in-law was a career Marine leader. My older brother, multiple cousins, and various nephews have also done stints in the armed forces. But the stories that stuck with me most came from my Uncle Louie, a close family friend who’d been a conscientious objector in the Korean War because of his deep Greek Orthodox faith. Over plates of roast lamb and pastitsio he’d prepared for us, he described how, as a conscientious objector, he was given two jobs: To cook for the other soldiers and to bury their bodies. Even at a young age, it pricked my conscience that a gentle man who was opposed to war was given the task of digging graves for the war dead.

I remembered this while working with Marcus Seymour on his essay about losing his faith in God after suffering profound traumas during his service in Afghanistan. Besieged by flashbacks and other classic symptoms of PTSD,3 Seymour was given the stateside job of planning and attending the funerals of fallen soldiers and notifying their families. He writes: “Where faith had once existed, fear now took its place. Where love had previously created connection, loneliness now created separation.”

When Neris Gonzalez was 23 years old, she was locked up, tortured, and raped at the local National Guard headquarters because she’d been teaching other Salvadoran peasants to read and count. Journalist Julia Lieblich details how it took Gonzalez months to come to consciousness again and years of therapy to be able to talk about these brutal experiences. Her faith in a just God has been integral to her slow but significant recovery from PTSD, but still she reminds us, “Torture has indelibly marked me.”

Other authors explore collective and intergenerational traumas. Rhonda V. Magee and Juan Villoro both elucidate the complexity and depth of “the legacies of white supremacy, colonialism, and genocide” that infuse all dimensions of life and the construction of selves. Magee notes that “so much of what we know about race is governed by hidden codes of silence,” but people of color “carry this woundedness in our bodies.” In Mexico, Villoro explains, “Direct access to the indigenous mentality was broken during the Conquest,” resulting in “a hermetic discourse whose decisive keys had been lost,” yet “that past was inherent to . . . Mexican national identity.” He asks, “Is it possible to recognize oneself in something one does not know?”

This issue is not for the faint of heart, and yet I find the pieces here to be uplifting because they provide us with models and methods for endurance, reparation, and the awakening of new possibilities.

You’ve probably gleaned that this issue is not for the faint of heart. Magee challenges us to “turn toward the things that pain us.” Drawing our attention to the increase in attacks on synagogues in the U.S., Robert Israel suggests we non-Jews need to do more than just show up for “one off” solidarity events. Matthew Kruger proposes that religion actually begins with doubt, when we move beyond the idea “that life is . . . reducible to purpose, success, or contribution to the world.” And yet I find the pieces here to be uplifting because they provide us with models and methods for endurance, reparation, and the awakening of new possibilities.

Seymour eventually discovers a divine spark while caring for others at the Kalighat Home for the Dying. Gonzalez continues to work for community healing and to mend the trauma in her own family. The Mexican writers Villoro highlights provide portals to the buried past, engage in “intellectual uprisings” and “intimate rebellions,” and “capture singular moments.”

Magee points out that we have practices at our disposal, such as embodied mindfulness, to help us “find the stamina and the capacity to stay with . . . the [difficult] things we might wish to bypass.” If we can “start with where we are,” she writes, we might “discern what we can do together from here, both brokenheartedly and bravely.”

Indeed, a key theme running through this issue is the value of friendship. Michael D. Jackson discusses Hannah Arendt’s “genius for friendship” forged in exile with other “conscious pariahs” who decided “to make an intellectual virtue out of [their] marginal and unassimilated status.” One of Charles Hallisey’s main takeaways from his work translating the Therigatha is “the power of intentional communities of friendship.” For these early Buddhist women, “Finding a friend draws . . . possibilities out of them, often possibilities that they didn’t know were there.”

Moreover, how people relate is inextricably linked to how they think. “Friendship also lay at the core of [Arendt’s] political philosophy since it exemplified the trust and openness to dialogue without which human beings cannot hope to create a common world,” Jackson explains. The women of the Therigatha learned through friendship how to “choose another tomorrow to live into.”

Jocelyne Cesari, Devin Singh, and Michelle Sanchez all employ conscious intellectual practices of empathy that enable them to read texts and history in expansive, assumption-questioning ways.

There are no easy consolations here, but you might discover how “the wounded voices of humanity” can lead to love-in-action, or renew your appreciation for “the small gestures” of friendship, or even be “beckoned into different kinds of possible futures.”

Notes:

- To quote Oxford professor Santanu Das, this poem is “one of those primal moments in the history of not just English but world poetry when lyric form bears most fully the trauma of modern industrial warfare.” Santanu Das, “ ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’, a Close Reading,” from the British Library website, Discovering Literature: 20th Century, May 25, 2016.

- One of Owen’s famous quotes was: “Above all I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.”

- Four classic categories of PTSD symptoms are re-experiencing (also called “intrusive memories”), avoidance, numbing, and hyperarousal. The condition also causes significant negative changes in thinking and mood.

Wendy McDowell is editor in chief of the Bulletin.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.