A Look Back

To Speak About God

HDS Photograph

By Krister Stendahl

On April 15, 2008, Krister Stendahl, former Dean of Harvard Divinity School and Mellon Professor of Divinity Emeritus at Harvard, died at the age of 86. It is difficult to describe fully—or, indeed, to overstate—the influence that he had on generations of Harvard students as well as on thousands of other people worldwide who knew him as a pioneer in ecumenical relations, a church leader, a New Testament scholar, or simply as a friend. Here at Harvard Divinity Bulletin, we benefited regularly from his wisdom and loving advice. In small tribute, we publish below an appropriate excerpt from the HDS Convocation Address he delivered in September 1984, just as he was leaving the School, where he had served since 1954, to become the Bishop of Stockholm in his native Sweden.

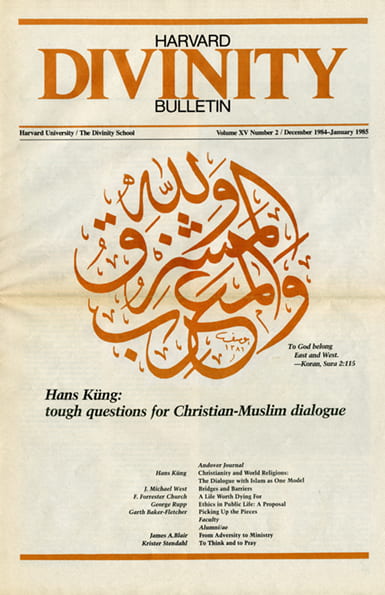

Harvard Divinity Bulletin, January 1985

To speak about God is wholly arrogant and holy arrogance. It is to think about what cannot be thought. Thinking relates one thing to another, that is, it is relative. But if God is anything, God is absolute. And to think is to grasp, to hold in one’s mind, to possess. But the sin of sins and the flaw of flaws is to think that we can possess God. A god comprehended is by definition no god. . . .

How to speak about God? By necessity we have to speak in human terms, or, as it is called in “learned” circles, anthropomorphic language, language shaped by how one thinks about human beings. There is great irony in the fact that the biblical tradition, perhaps most intensely but not exclusively in its Christian editions, has maximized the anthropomorphic language, speaking about God as a human person.

In the interest of stressing that God is personal and in the interest of protecting the understanding of the faith as a relation-ship, the precious I-Thou, what else could happen but an intensified expression and experience of God in human terms—the Lord, the Father, the Judge, and much more? But all of them are personal and, it seems, all male. The terms are personal by some inner necessity, male by habit and of-ten without much thought and out of the cultural dominance of us men.

The irony lies in the fact that, as we all know, the Ten Commandments insist that it is wrong to make for ourselves images of God. And the prophets can get rather funny, so superior do they think themselves when thy ridicule the graven images. There might be good reason, especially in more fundamentalist climates, to apply the commandment against the images not only to images of stone and wood and metal, but also to the mental, theological, and intellectual images with which the tradition lives. But theologians always have known that it is, so to say, equally true to say about God that he is white as it is to say that she is black. And exegetes know full well that when in Genesis we are told that we are created in God’s image, we are not per-mitted to turn it around and picture God in our image. We who live in Cambridge should know the importance of one-way traffic—an important rule of hermeneutics and interpretation of Scripture. And yet the irrepressible desire and need for personal language causes the anthropomorphisms to intensify and excel. . . .

My own feeling is that we have over-done anthropomorphism in the interest of I-Thou-ing ourselves through life and into eternity. And, I take it, we will be surprised. I take it that there is nothing wrong in also thinking about God in a dialectical way as Energy, Wisdom, Light, Justice. . . .

I have come to love more and more the Trinity, not as a statement by which people increase the tensions in Christendom or measure the orthodoxy of the other, but for the very simple reason that the Trinity plays fast and loose with the three “per-sons”—one of which is only loosely a “per-son,” for, in the Greek language, the Spirit is it. And think of the risky stretching of monotheism that is involved in the trinitarian language.

Or think of that dynamic vision of the Trinity which caused the Eastern churches to resist attempts by the orderly and hierarchical West to add the filioque. For the East had it right when they thought of the Spirit as God’s creative energies which permeate all. I think I see all this somehow as Paul does, when he writes those words to which I return again and again as I ponder how to think and how to pray: “And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being changed into his like-ness from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord, the Spirit” (2 Cor. 3:18).

The nature of biblical language helps us, so that no language and no image is allowed to harden into “a graven image” which could encourage intellectual idolatry. That is why Harvard Divinity School’s biblical departments have such a great gift to give to us all. For here we sure are strong in demonstrating the diversity of the various theologies within the Bible.

And for me it seems quite clear that it is wonderful to have four gospels, pro-vided that you are not made uptight by that apologetic stance that kills most religion. That is to say, if you get defensive, the variations become embarrassing. But to be defensive for God is a pitiful thing. Who defends whom? Rather, I think of the diversity as enrichment, and thereby, when I look at the four gospels I do not like to make a transparency of each of them, put them on top of each other, and throw the light through them. That becomes blur—perhaps holy blur, but sill blur. No, I look at one gospel, one image at a time, let it sink in, and the variations become an enrichment. The variations also protect God, Christ, and the Bible herself from idolatrous use, because there will always be kaleidoscopic changing; and somehow one image puts the other in check, counteracting an image from hardening into more than it is: one image among many.

Biblical language is often a quick, light, and delightful language, which cannot bear the superstructures that have been built upon it. It will always suffer from our greed when we try to squeeze more out of this holy orange than was ever meant or is ever possible. One of the ways of avoiding such greed and misunderstanding is to learn from the Jewish sages—and perhaps Jesus also was on that wonderful trajectory—from Hillel to Woody Allen. Perhaps sometimes we must perceive the twinkle in Jesus’ eye as we listen to his words. We have to find the right nature of this word so that we do not overuse it in our desire for knowing and believing more and more. Jesus’ speech is far less pompous and far more humorous than we think. In those days if any shepherd left the 99 in the wilderness and went after one, that shepherd would be fired if he was found out. And what farmer was ever so dumb as to spread the seed equally on his patch, regardless of paths and roads and all? So let us lighten it up. It may well be that he said much of his words with a smile. Joy is closer to God than seriousness. Why? Because when I am serious I tend to be self-centered, but when I am joyful I tend to forget myself. . . .

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.