Perspective

The Stories within Our Stories

Illustration by Brian Hubble. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Wendy McDowell

In my previous job for the National Council of Churches, one of my most memorable assignments involved accompanying Nobel Peace Prize laureate Rigoberta Menchú Tum on a Manhattan press tour. The tour had been sponsored by human rights organizations to allow her to defend herself against academic and media attacks on the “truthfulness” of her testimony Me llamo Rigoberta Menchú y así me nació la conciencia, which had been transcribed from taped interviews by Elizabeth Burgos, translated into English, and published in 1984 as I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian Woman in Guatemala.

At stake were complex issues and struggles related to the history of land, politics, and ideology in Guatemala. Yet the “Rigoberta Menchú controversy” was only able to gain momentum by exploiting the power differential that already existed between two different narrative styles: the written, fact-based, product-focused style of the elite Western media and academia, and the oral, collective, process-oriented style of storytellers outside the European tradition. In indigenous accounts such as Menchú’s, as anthropologist Michael Jackson describes in The Politics of Storytelling, “far less emphasis is given to the heroic career of individuals or the delineation of personal identity, and . . . lives are depicted as inescapably embedded in social, political, and historical affairs, as well as deeply integrated with worldviews and physical environments.” In these storytelling traditions, a telling of one’s “personal” journey is supposed to incorporate the stories and experiences of others, as did Menchú’s account of the violence visited upon her family and her fellow indigenous Guatemalans.

The very narrative strategies that allow for a more socially embedded, collective account of individual existence were used to attempt to disqualify this K’iche’ Mayan woman from speaking for her people, even though Menchú never intended for her oral testimonios to be a written “autobiography” in keeping with European conventions. Perhaps not surprisingly, this “controversy” proved to have little to no influence on the opinions of the indigenous peoples throughout the world to whom Menchú considers herself to be accountable.

Since then, I have become more suspicious of stories that claim to have a corner on “truth,” even well-intentioned ones. I am aware that narratives, and certain narrative styles, can be used as weapons as much as they are tools of revelation and meaning-making. Though I believe in the value of fair, accurate news reporting, I have come to wonder if, as poet Joanna Klink so poignantly puts it in her four-part poem “Feverish,” “. . . Perhaps / the way to despair is based in / certainty. . . .” At the same time, I have become more appreciative of narratives from any tradition, and in any literary form, which explicitly acknowledge their social and political embeddedness.

I was surprised and excited, then, when two contributors to the Dialogue section asked me (separately from each other) if they could co-author pieces with colleagues. This seemed especially appropriate since their respective topics had to do with economic global neighborliness and interfaith dialogue. I was equally delighted when I read through initial drafts from Elizabeth Siwo-Okundi and Kurt Shaw. Though written in isolation from each other and addressing two different urgent situations (orphans in Kenya and child soldiers in Colombia), they seemed to be in close conversation. Both pieces call us to listen to the prophetic voices (and stories) of marginalized children, and both are clear exhortations to consider our own lives and fates to be linked to those whose struggles render them vulnerable and hidden from our view.

Though many of the pieces in this current issue suggest that we should embrace a collective, global ethic, they also critique some of the ways we tend to imagine our collective groups (families, nations, or religious groups). Nancy Nienhuis asks religious leaders to place the physical safety of family members over certain theological notions. Richard Delacy questions the image of an idealized village (the “real” India) in Swades that doesn’t acknowledge economic exploitation. Amy Sullivan explores how suburban evangelicals in the U.S. have drawn firmer or more porous boundaries around their communities.

It also strikes me that many of the pieces in this issue are actually stories about storytelling, and as such they are transparent to the “social process of storytelling” (Jackson again). Shaw even uses the term “collective autobiography” to describe how child soldiers create a redeemed story of themselves through film. Siwo-Okundi reads new texts and subtexts in some well-known biblical stories. Christian Wiman willingly accepts that all attempts to make narratives about God or faith are necessarily insufficient.

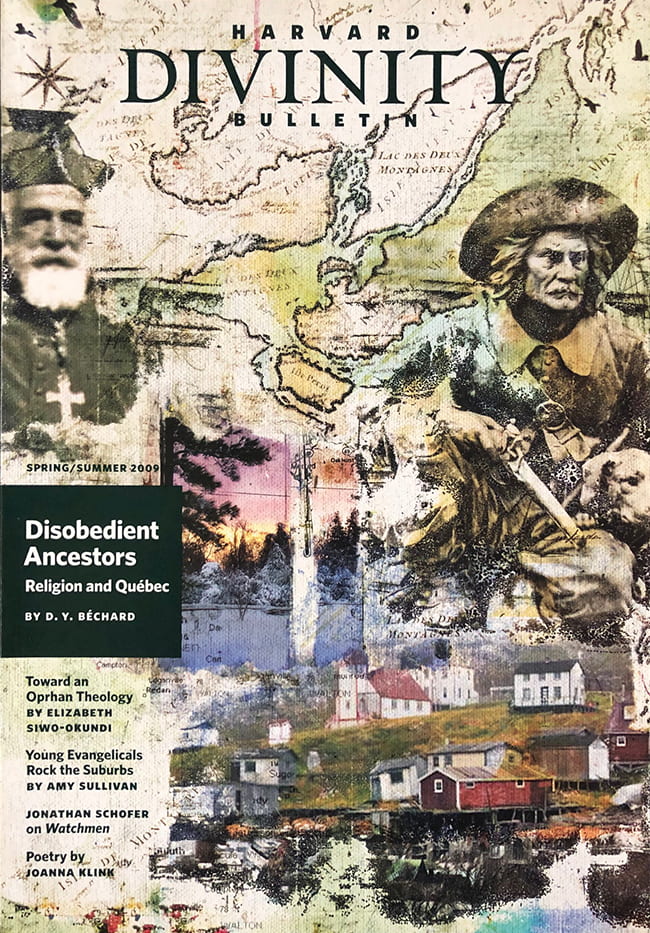

Jonathan Schofer provides some thought-provoking ethical reflections on Watchmen, which, as he explains, “is a comic about comics.” One of the themes that Schofer finds in this work “is that narratives have significant causal impacts upon our lives. We not only tell narratives but discover them and live them out.” D. Y. Béchard’s cover article about Québec is a living, breathing example of this theme, and is itself a narrative about several kinds of narratives: stories his father and relatives have told him, historical accounts of the region, and French-Canadian folktales.

Though Béchard’s work is the product of laborious research and literary craftsmanship, it manages to point to the inchoate and mysterious, never resting on certitude or definitiveness. These are my own favorite kinds of works of art, because they act as signposts to “the silence that is . . . the source” (Wiman) of all of our attempts to describe and order human experience.

I hope you will notice the various narrative sources and styles represented here. Perhaps you will respond to, or even “live out,” one of them in a way that alleviates the suffering of others. The Bulletin, too, is always engaged in a “social process of storytelling,” and the more social, the better.

Wendy McDowell is senior editor of the Bulletin.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.