Perspective

The Poetry of Pragmatism

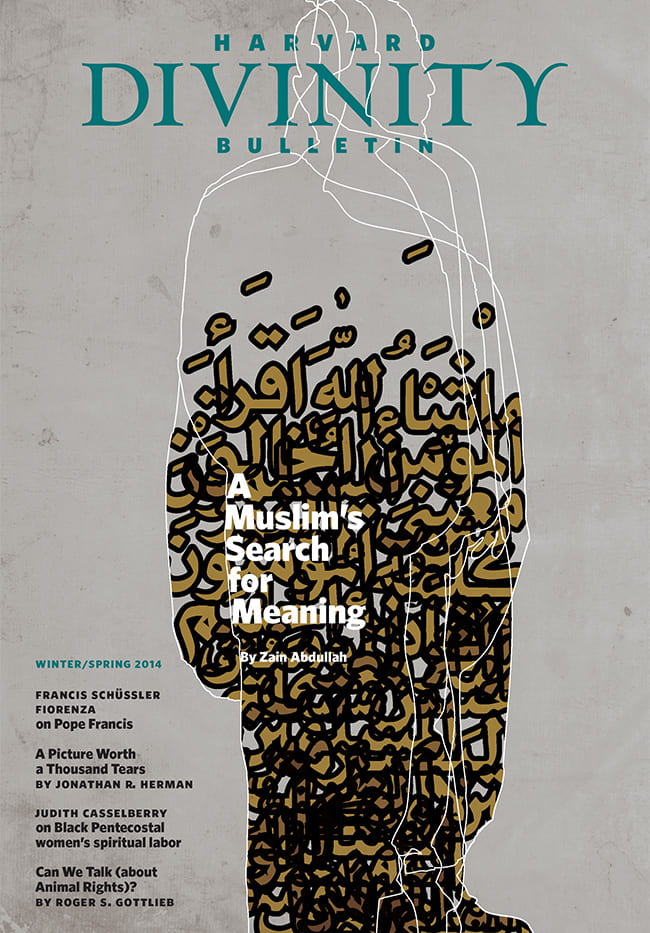

Illustration by Reza Abedini. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Wendy McDowell

When President Obama addressed the nation after Nelson Mandela’s death, he reflected, “The very first political action, the first thing I ever did that involved an issue or policy or politics, was to protest against apartheid.” Obama’s words resonated with me. Participating in an activist movement to persuade my small liberal arts college to divest from South Africa was the first time I experienced the transformative power of a collective voice. However, it was also my first encounter with the limits of dialogue.

After our student-run anti-apartheid group had been going full steam for a while, the school’s board of trustees agreed to grant us a meeting.1 I was one of four students elected to speak for our group. We marshaled substantial evidence about the evils of apartheid and the virtues of socially responsible investing. In our meeting, we described how other colleges and universities had elected to invest their funds more responsibly without hurting their portfolios in the least.2 One or two trustees seemed genuinely willing to engage with us, but most gazed at us dispassionately. Finally, one of the trustees declared impatiently, “Everything you say might be true, but we’re still not going to divest.” Naturally, we asked, “Why not?” Quite matter-of-factly, he replied, “Because no one is going to tell us what to do with our money!” At the time, I was flabbergasted (looking back, I was the youngest—and most naïve—person in the room). I turned red and said something like, “How can you hear about such profound suffering and inequality, and not care?” This was met with the equivalent of a paternalistic shrug, and it was clear that our meeting was over.

On an extremely small, lower-stakes scale, our group had encountered what Mandela and his African National Congress compatriots had experienced after years of pursuing the legally acceptable channels to make change in South Africa: a realization that dialogue was not possible so long as the governing group remained able to protect its status and wealth. For me, this involved a certain loss of innocence, but it also ushered me into a deeper, more pragmatic understanding of power and political tactics.

I was thus heartened to see that among the many reflections on Mandela’s life and legacy, some did not shy away from addressing his eventual support of “violent resistance.”3 Natasha Lennard astutely commented:

We erroneously isolate certain acts to deem “violent” or “nonviolent”—then “justifiably violent” or not, and so on—and in so doing we miss that there’s never a singular “violence”: there’s an ongoing dialectic of violent and counter-violent acts.

It’s within such a dialectic that we understand Mandela’s support of violence. His relationship to armed and violent struggle is nuanced and certainly not unique to him. He knew counter-violence was necessary in his violent context. He . . . also expressed that he and his ANC comrades prioritized the reduction of harm to human bodies.4

Mandela was a stalwart advocate of “nonviolent” protest and dialogue, as am I, but, as George Steiner suggests in his important book about language and politics in Nazi-era Germany, there are times “that the beauty and truth of language are inadequate to cope with human suffering and the advance of barbarism. Man must find a poetry more immediate and helpful to man than that of words: a poetry of action.”5

Steiner appreciates the immense “reserves of life” in our languages, but he is clear-eyed about what happens when language is used to “run hell”: it “get[s]the habits of hell into its syntax” (100).6 This cancerous infection of language occurred in South Africa, which is why the “poetry of action” exhibited by those who sang, marched, were imprisoned, and died for their liberation awakened political consciousnesses around the globe.

In this issue of the Bulletin, I am struck by the complexity and bravery with which the authors address issues, events, and groups about which we often find ourselves unable to dialogue—because acts of violence or deprivation can render us speechless, slip us into denial, or drive us into opposing camps. Roger S. Gottlieb encourages us to truly “look, carefully, slowly” at the senseless violence we inflict on animals. T. Robinson Ahlstrom exhorts us to see “alleviating the plight of children” as the “moral imperative of our generation.” Zain Abdullah models how to “break through the reifications and false dichotomies” concerning Muslims. And both Jonathan Herman and Suzanne Smith draw our attention to how the atrocities of the Holocaust continue to shape our moral conversations.

Yet the essays here also reveal how those, like Mandela, who embody a pragmatic politics spur us on to reflect, to narrate, and to open dialogue. There are high profile examples, including Pope Francis (discussed by Francis Schüssler Fiorenza), and the protestors in Egypt (observed by Ahmed Ragab). But more often, the authors find inspiration in their families and communities: Michele Somerville’s son with Asperger syndrome who embraces work at a soup kitchen; Herman’s relative who does not relent until he reunites a family torn apart by war and genocide; the health care professionals referenced in Tamara Mann’s book review, who care for our homeless and poor; the Black Pentecostal altar workers Judith Casselberry studies, who look out for the spiritual lives of others; the children and refugees from South Sudan who have led Adrie Kusserow to do humanitarian work and write poetry about “our responsibility for the lives of others” (Michael Jackson’s review); and Gottlieb’s animals, who show us how to be playful, loyal companions and protective guardians of our young. Though there are clear, moral stands to be found in these pages, these authors tend to take a pragmatic approach, revealing places to find common ground, improve our responses, and make things a “little bit better” (Gottlieb).

All this to say: I hope Mandela would not mind being referenced in this particular issue, focused as it is, not on making saints, but on pressing us fallible human beings to be more respectful of one another, more thoughtful (and effective) in our words and actions, and more spiritual in our orientation.

Notes:

- In hindsight, the school was embarrassed by the publicity the robust protests garnered, and attempted various strategies to diffuse them.

- By the mid-1980s, at least 155 United States and Canadian colleges and universities had either partially or totally divested from businesses active in South Africa.

- As Emmett Rensin wrote in USA Today (“Remember Mandela for Violence and Peace,” December 9, 2013), acknowledging how Mandela turned to “limited violence” allows us to “appreciate Mandela in totality.”

- Lennard, “What Nelson Mandela Can Teach Us All about Violence,” Salon.com, December 8, 2013.

- George Steiner, Language and Silence (1958; Yale University Press, 1998), 103.

- Steiner argues, “Something will happen to the words. Something of the lies and sadism will settle in the marrow of the language. . . . The language will no longer grow and freshen” (101).

Wendy McDowell is senior editor of the Bulletin.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.