Featured

The Obsidian Mirror

Mexican Archaeology and Literature in DialogueNezahualcoyotl (Fasting Coyote), the fifteenth-century poet-ruler of Tetzcoco, from the Codex Ixtlilxochitl (1582), 106r. Ms. Mex. 65-71, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

By Juan Villoro

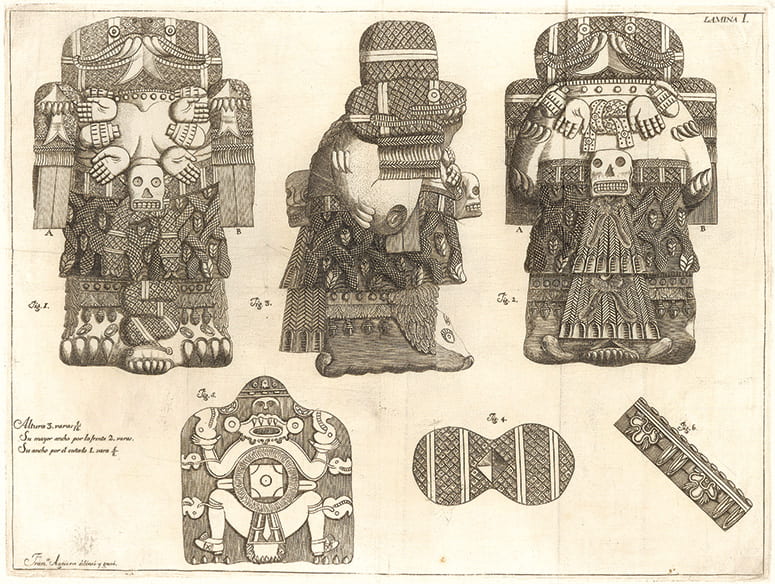

In 1790, the effigy of the Aztec goddess Coatlicue was discovered by accident in Mexico City. The huge stone block, with serpents and skulls carved on it, both captivated and horrified those who saw it. It was taken to the city’s university, where it was exhibited for a short time. The authorities of New Spain feared that its presence would reactivate the ancient faith of the indigenous inhabitants. The impact of this aesthetic and religious expression from the pre-Hispanic world was akin to terror. The goddess was laid to rest once again. In 1804, during his stay in Mexico City, Alexander von Humboldt (1759–1859), who had read about the Coatlicue, requested permission to see the statue. For a few days, she returned to the surface of the earth. It was only in the nineteenth century that her disconcerting figure became an object of study and, gradually, admiration. In “El arte de México: Materia y sentido” (The art of Mexico: Material and meaning, 1977), Octavio Paz (1914–1998) wrote, “The evolution of the Coatlicue—from goddess to demon, demon to monster, and monster to masterpiece—illustrates the changes in our sensibility over the last four hundred years.” The image of the deity that emerges from the past to disturb the present summarizes our dealings with the cultures of origin. Notices from that radically earlier time have been received with astonishment and horror.

Direct access to the indigenous mentality was broken during the Conquest. After most of the codices were destroyed and the temples were burned, some enlightened friars, suddenly turned anthropologists, tried to restore this legacy, but they could only do so in a hybrid and fragmented way, blending the accounts of native informants with their own conception of reality. The ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica were subjected to hypotheses and conjectures that were not always verifiable, as well as esoteric interpretations, forming a hermetic discourse whose decisive keys had been lost. However, in a way that was not always precise, that past was inherent to our makeup. An independent Mexico could not be explained without the myths and legends, the plants and animals, the culinary dishes and use of colors, words, and customs that came from a mysterious previous era. Mexican national identity was created from that dark matter.

Is it possible to recognize oneself in something one does not know? In his book The Buried Mirror (1992), Carlos Fuentes (1928–2012) took up ideas that Octavio Paz had put forth since 1950 in The Labyrinth of Solitude. Fuentes eloquently associates Mexicans’ conflicted identity with the legend of Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent at the heart of several Mesoamerican peoples’ theodicies. An enlightened god, Quetzalcoatl lived for knowledge, but he did not know his own face. That shortcoming gave rise to a curious divine dispute. The pre-Hispanic sky was a stage for gods in conflict. Tezcatlipoca, the Lord of Fatality, had a smoking obsidian mirror—whoever looked into it would gaze upon their inevitable destiny. In order to defeat Quetzalcoatl, Tezcatlipoca made him look at his own face. On the polished obsidian surface, that harmony-seeking god beheld an aberration: a confusing creature, part bird and part reptile. Horrified by his image, he threw down the mirror and fled from the people who had venerated him. The mirror remained buried like a time capsule, waiting to acquire another meaning. Fuentes used this legend to express the drama of Mexicans confronting ourselves. We will only be worthy of our identity when we accept the contradictory features that characterize us. As Paz expressed in The Labyrinth of Solitude, and later in Posdata (1970), this exercise is not intended to separate Mexicans from others, making them exceptional or “unique.” On the contrary, overcoming the complex of being “different” allows us to establish a dialogue of plurality with other cultures, equity among differences.

Like the Coatlicue, Tezcatlipoca’s mirror produced an uneasy sense of awe—a fear derived less from the objects themselves than from the way they were seen. Consequently, we opted for the reassuring remedy of hiding them. The obsidian disc and the incomprehensible idols were buried.

Archaeology would bring them back. The British writer D. H. Lawrence (1885–1930) traveled to Mexico in 1923, when several effigies were being excavated. This confirmed his theory that telluric and religious forces were returning to amend a reality that the West had vulgarized. In 1926, he published The Plumed Serpent, a novel more interesting as theosophical speculation than as literature. Two years earlier, Mexican writer José Juan Tablada (1870–1945) had published excerpts of a similar novel he called La resurrección de los ídolos (The resurrection of idols, 1924) in the newspaper El Universal. It is possible that Lawrence had read these passages, but what is certain is that an atmosphere of archaeological recovery was in the air.

The Great Coatlicue, from Antonio de León y Gama, Descripción histórica y cronológica de las dos piedras que hallaron en la Plaza Principal de México (1792), plate 1. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University

In his book Historia de la arqueología del México antiguo (History of the archaeology of ancient Mexico, 2017), Eduardo Matos Moctezuma points to the importance of the Mexican Revolution to understand the pre-Hispanic cultural heritage differently. After the armed struggle from 1910 to 1920, important archaeological recovery was carried out, largely guided by Manuel Gamio (1883–1960). In addition to continuing work at sites such as Teotihuacan, which had been explored since the seventeenth-century efforts of scientist and writer Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645–1700), excavations were made at Copilco and Cuicuilco, making Mexico City the setting of discovery. The streets that Lawrence and Tablada strolled along extended over an underground stage that was beginning to emerge. The effigies, made of stone, inscribed in mineral time, were in no rush to communicate their messages. Little by little, such messages would come to us.

In 1978, a decisive discovery was made in an emblematic place in the Mexican capital, in downtown Mexico City, at the “center of centers”: the remains of the Aztec Templo Mayor returned to the surface. Eduardo Matos Moctezuma led these efforts, and he continues to head the Urban Archaeology Program to this day. On several occasions, he has referred to that moment when archaeologists of any era make a discovery as “a flashlight illuminating the past.” That light has been instrumental in rebuilding the cultural mosaic that we depend on, often without even knowing it.

While the archaeologists of the twentieth century were uncovering the lost language of the stones, literature imagined links with a culture that had seemed doomed to be lost in the haze of time. In Octavio Paz y arqueología (Octavio Paz and archaeology, 2019), Matos wrote: “The archaeologist penetrates the arcana of the past via the time-magic that is archaeology. The poet also achieves this by passing through the tenuous curtain separating the living from the dead to get closer to the window of time.”

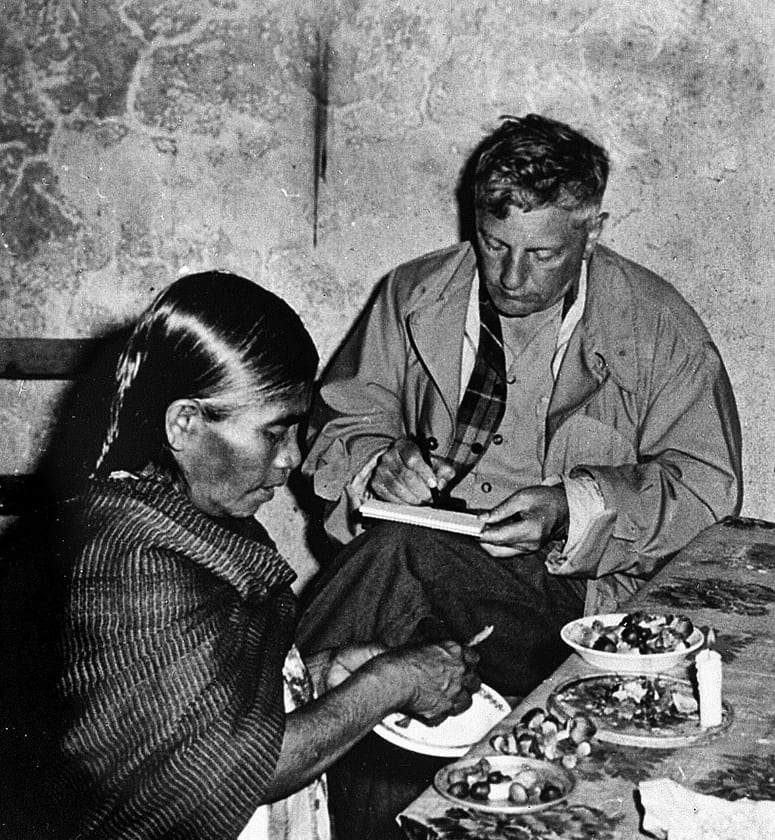

My generation began publishing in the 1970s and became interested in the indigenous world thanks to archaeological discoveries, but also thanks to the stimuli from an unexpected source: the counterculture. Fernando Benítez’s chronicle, Los hongos alucinantes (Hallucinogenic mushrooms, 1964), was essential for a vernacular tradition—embodied in the figure of the modern-day Mazatec priestess María Sabina (1894–1985)—to reach the Age of Aquarius. The same can be said of Carlos Castaneda’s The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge (1968), a research project that was originally conceived as an anthropology thesis on a Yaqui shaman, which became the magical tome of middle-class youth seeking an “alternate reality.”

Harvard research associate and ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson interviewing Mazatec curer María Sabina. Tina and R. Gordon Wasson Ethnomycological Collection Archives, Archives of the Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, Harvard University

During his time in Mexico, Aldous Huxley (1894–1963) introduced Timothy Leary (1920–1996) to mind-blowing psilocybin mushrooms. A doctor of psychology at Harvard University, Leary researched the possibilities of expanding consciousness through the regulated use of narcotics. In the early 1960s, he became the ultimate LSD prophet. Expelled from the university circuit, he took refuge at the Hotel Catalina in Zihuatanejo, where he founded a kind of “Club Med of the mind.” In the summers of 1962 and 1963, Leary and some 30 others gathered in that Mexican coastal village to open the “doors of perception.” Carlos Castaneda (1925–1998) was possibly part of that group, as was a CIA agent who denounced the experiment to the authorities in Mexico and the United States.

Zihuatanejo was the world headquarters for the expansion of consciousness. Under pressure from the United States, the Mexican government asked Leary to leave the country. In his interview with the authorities, the acid guru warned about the dangers of prohibitionism and proposed that Mexico become a “psychedelic Switzerland,” administering recreational drugs according to medical and cultural criteria. A Pandora’s box had been opened, leading to a dilemma: either allow a controlled use of hallucinogens, in the way that the original peoples of Mexico have lived with endemic plants for centuries, or let organized crime run rampant. We know the outcome: More than half a century later, Mexico is bleeding to death in a futile war against drug trafficking.

It is worth emphasizing that the counterculture gave the past an unusual novelty. Until then, our schooling had referred to pre-Hispanic grandeur as something unalterable and in the past. Thanks to the heralds of psychedelia, from beat writers to rock poets, India, China, Peru, and Mexico were seen as reservoirs of transcendental wisdom capable of altering the present.

The counterculture popularized discussions that decades earlier only had taken place in “high culture” circles. In 1939, critic and editor Philip Rhav (1908–1973) published an essay in the Kenyon Review that would spark literary discussion in the United States. The appealing title of the text was “Paleface and Redskin.” Rhav divided the writers of his country between the “palefaces,” who, in the manner of Henry James (1843–1916), sought elegant interior spaces, and the “redskins,” who, in the manner of Herman Melville (1819–1891), preferred the uncertainties of the outdoors. The former respected classical forms (using saddles like cowboys); the latter were iconoclasts (who rode bareback). Without saying it openly, in his classification, Rhav preferred the redskins. Cherokees, Comanches, and Apaches acquired the prestige of cultural transgressors. Without taking full account of the Indians who served him as metaphor, Rhav brought them into the discussion like a noisy cavalcade.

Mexico has been fertile ground for “outcasts,” the “redskinned” writers of the American tradition, from Langston Hughes (1901–1967) and Hart Crane (1899–1932) to Jack Kerouac (1922–1969), William S. Burroughs (1914–1997), and Ken Kesey (1935–2001), a fundamental figure of psychedelia.

In the 1960s and 70s, the counterculture lent the indigenous legacy a sense of “modernity.” Those who studied anthropology or archaeology at that time delved into the systematic study of origin cultures.

“The path to ourselves is through others,” Octavio Paz pointed out when speaking of the influence of African art on Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) during his cubist period: in order to return to the point of departure, we must take a detour. In the 1960s and 70s, the counterculture lent the indigenous legacy a sense of “modernity.” Those who studied anthropology or archaeology at that time delved into the systematic study of origin cultures. Meanwhile, artists searched for intuitive contacts in this lush bazaar of symbols. José Agustín, the main narrator of the Mexican counterculture (renamed “La Onda”—The Wave—in Mexico), began his career as a disciple of J. D. Salinger (1919–2010). After approaching existentialism, surrealism, Carl Jung’s theories of the collective unconscious, and the New Age philosophy of Alan Watts (1915–1973), Agustín studied Nahuatl and rediscovered the messages of ancient Mexico in novels such as Cerca del fuego (Near the fire, 1986).

The counterculture revealed that the past could be pop, which produced all kinds of distortions and overanalyses. Carlos Monsiváis (1938–2010) left us an ironic aphorism about the way that psychedelia perceived mythical figures: “Coatlicue no longer speaks because she’s passed out.” The will to be “redskinned” did not necessarily assume the study of native peoples. Taking on a “savage” condition became a generalized intellectual stance that years later would shape the best-known novel about that period: Los detectives salvajes (The Savage Detectives, 1998), by Roberto Bolaño (1953–2003).

My first book, La noche navegable (Waterway night, 1980), is a compilation of stories written in the 1970s. The story that gives it its title takes place in the archaeological zone of Monte Albán, in the state of Oaxaca. The plot is about some friends who get trapped there and must spend the night. In this story of love, friendship, and possible betrayal, the most significant element is the context: the characters act “differently,” magnetized by an unknown force emanating from the ruins, an unconscious stimulus to which they naively subject themselves.

In La noche navegable, the idea of historical legacy is remote and esoteric. A decade later, in 1989, I published a travel book about Yucatán. Throughout my journey, I was amazed that the first inhabitants of the peninsula were seen as extratemporal beings. “In Mérida anything could be thought about the Maya, except that they are alive. The city expresses its pride in the pyramids to the extent that they are a historical legacy. The Maya are not spoken of in the present tense. Anything outside—the green, the jungle, the sisal agave plants—is the world of the peasants, the Indians, the others.”

Five years later, on January 1, 1994, the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) took up arms in Chiapas to protest the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement. While one sector of the country dreamed of acquiring consumer goods from the so-called first world, another lived a nightmare of backwardness and oblivion. The Zapatista movement took up unfulfilled ideals of the Mexican Revolution (such as the inclusion of the dispossessed people in the national project, the communal recovery of land, and the struggle for a direct nonrepresentative democracy) and put the indigenous question on the agenda of modernity, showing that this struggle did not belong to the past, but rather the present.

Eduardo Matos Moctezuma agrees with Octavio Paz that the National Museum of Anthropology was conceived as a temple whose main altar is presided over by two Aztec pieces: the Great Coatlicue and the Piedra del Sol, or Sunstone. This museological sacralization helped post-Revolution administrations proudly celebrate pre-Hispanic relics while ignoring the commitment of Emiliano Zapata and the reality of indigenous peoples.

Left: The Great Coatlicue, Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City. Right: The Piedra del Sol, or Sunstone, Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City. Photos: Salvador Guilliem Arroyo

Starting in 1994, the Zapatistas, and the indigenous movements that joined them or initiated complementary struggles, revealed the surprising novelty of the past. Its effect was political, but also intellectual, as it prompted the present to be understood through the lens of codes from another era. A few months after the uprising, I wrote a chronicle about the Mexico City subway. In line with public debate at the time, the subterranean world to me seemed like a modern representation of the cave of origin, common to most pre-Hispanic cosmogonies, and of Mictlan, the underworld destiny of the dead. In the subway, as in Zapatista discourse, an atavistic heritage coexists with postmodern symbols. When the first line opened in 1969, it boasted the most modern technology available, imported from France. On the other hand, many stations had Nahuatl names, and a style that imitated pre-Columbian friezes, icons that turned cartography into a pictographic codex, and a pyramid found at the Pino Suárez station were signs of an unusual “pre-Hispanic modernity.” In 1994, this clash of symbols gave rise to the text, “La ciudad es el cielo del metro” (“The City Is the Sky of the Metro”), included years later in my El vértigo horizontal: Una ciudad llamada México (2018, Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico, 2021).

The trajectory that runs from the “Waterway night” tale (1980) to the subway chronicle (1994) bears witness to a shift: The indigenous world ceases to be a spellbound and inscrutable backdrop and becomes an explanation of the present.

I mention this personal itinerary because it accounts for the different ways in which the indigenous past has been viewed by my generation. The trajectory that runs from the “Waterway night” tale (1980) to the subway chronicle (1994) bears witness to a shift: The indigenous world ceases to be a spellbound and inscrutable backdrop and becomes an explanation of the present.

The dialogue between Mexican archaeology and literature has had several key moments. I will consider a few here. The story “Chac Mool,” published by Carlos Fuentes in his first book, Los días enmascarados (The masked days, 1954), is about a statue of a Toltec and Maya god that alters contemporary life. The pre-Hispanic world returns in the form of a threat. The narrator inherits the statue from Filiberto, a friend who drowns in Acapulco and leaves a diary about the disturbing effigy that comes to life when it makes contact with water. The narrator claims Filiberto’s corpse and takes it back to his house, where a disgusting-looking “yellow Indian” opens the door for him and asks him to take the corpse to the basement, the underground environment to which relics are often relegated. The ritual comes full circle: The friend who has died from the influence of the water-dominating god will occupy the place held by the statue. In this short story, the vision of the past is ambivalent; the ancient world has been sullied, but contact with it is terrible: Chac Mool returns seeking revenge.

Ten years later, in 1964, Elena Garro (1916–1998) conceived an exceptional story, “La culpa es de los tlaxcaltecas” (Blame the Tlaxcaltecs), included in her book La semana de colores (The week of colors). As we know, the conquest of Mexico was possible, among other reasons, because the Tlaxcaltecs joined the Spaniards to fight the Aztecs, who had cruelly subjected them. Since then, the word tlaxcalteca has been unfairly associated with “traitor.” In Garro’s story, this legendary culpability extends to women, warped into mistrustful and irrational figures by a machista and patriarchal tradition.

The plot links two time periods: Laura’s domestic life in the twentieth century and her pre-Hispanic world where she has an affair. One sentence defines the logic of the text: “Todo lo increíble es verdadero” (Everything incredible is true). Laura is married to Pablo, a decent average man. On a bridge linking the two realities, she meets a wounded indigenous man who survived the Conquest and whom she calls “primo-marido” (cousin-husband). When she feels the warrior’s blood on her body, she thinks that they are one being. In contrast, she finds her husband boring and controlling, someone who “no hablaba con palabras sino con letras” (spoke not in words but in letters). Laura loves the warrior without being disloyal, because her passion is consummated in another era to which only she has access. However, she is marked by the stigma of her gender. In the present—the comfortable yet tedious universe where she has a maid and electrical appliances—her affair with her “primo-marido” represents an incestuous transgression, alien to the discriminatory privileges of her class. Her lover is dangerous, an Indian willing to kidnap a white woman. He tells her, “Traidora te conocí y así te quise” (You were a traitor when I met you, and that is how I loved you). Stigmatized in her own era by the fact of being a woman, Laura is unconditionally accepted in the warrior’s time-out-of-time. In the Fuentes short story “Chac Mool,” the past appears as a fascinating and destructive force. In “Blame the Tlaxcaltecs” the past is represented in the risky option of loving the indigenous; rather than a condemnation, it is a liberation. It would take many years for Elena Garro’s pioneering gaze to be seen as more than fantasy literature.

Some years later, in 1972, José Emilio Pacheco (1939–2014) wrote his own version of this encounter with the past in “La fiesta brava” (The bullfight), a story from the book El principio del placer (The pleasure principle). Pacheco conceived a suggestive story-within-a-story. The main character, Andrés Quintana, is a failed writer who has the opportunity to collaborate in an American magazine printed in Mexico and submits an interesting but unsuccessful piece called “The Bullfight,” featuring Captain Keller, a Vietnam veteran visiting Mexico. Again, the effigy of the Coatlicue is both attractive and bewildering. Every day, Keller goes to the Museum of Anthropology to sketch the Aztec goddess. His obsessive interest in the ancient world brings the former soldier into contact with secret emissaries from that culture and, finally, with the sacrificial stone.

Quintana delivers his story, and the editor dismisses it; he reminds Quintana that Carlos Fuentes had already exhausted that topic and that Julio Cortázar (1914–1984) blended the present with the Aztec world in his tale “La noche bocarriba” (“The Night Faceup,” 1967). This story by Cortázar depicts a tragic ending as well as Andrés Quintana’s story. On top of that, the narrative’s condemnation of American imperialism and the Vietnam War seems to the editor not only demagogic but also cynical: How could Quintana write an anti-Yankee story for a magazine financed by the United States?

In the words of Octavio Paz, “Sacrifice did not bring about salvation in another world, but cosmic health.”

Quintana’s poorly written tale serves as the source material for Pacheco’s accomplished story. Although the editor’s criticism is directed at the “tale,” it is suggested that he also takes revenge on a personal level, since Quintana married the woman the editor loved. In the rejected story, bearing the same title as Pacheco’s, time-crossing is used for dramatic effect and the Aztec world appears supernatural, incomprehensible, and punitive. Anyone who disturbs the slumber of that myth deserves to die. The ritual of human sacrifice appears as a settling of accounts, far from its authentic religious meaning of staving off an adverse ecosystem—dominated by droughts, plagues, and floods—by offering what is most precious: human life. In the words of Octavio Paz, “Sacrifice did not bring about salvation in another world, but cosmic health.”

By placing an “unpublishable” story within his own story, Pacheco indirectly criticizes those who have caricatured the pre-Hispanic legacy as a crypt of symbols that enables the conceiving of “special effects.” By saying that Carlos Fuentes “had already exhausted the subject,” perhaps the editor also suggests that Fuentes had gone down a dead end, inventing a past that never existed and arbitrarily associating it with the present. Andrés Quintana, who is fed up with living off his work as an English–Spanish translator, becomes interested in the Conquest out of political rather than literary zeal because he wants to write an attention-grabbing parable about Vietnam. In an interesting and perhaps contradictory manner, Pacheco criticizes this transposition of imperialisms but makes Quintana suffer the same fate as Captain Keller, suggesting at the end of his own tale that the vengeful forces of the Aztecs continue to operate underground.

If narrative has focused on combining and confronting the different eras of Mexican history, poetry has sought to capture singular moments that are capable of revealing that what happened yesterday is still happening today, like the flower in the wonderful poem, “What If You Slept?” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834):

What if you slept

And what if

In your sleep,

You dreamed

And what if

In your dream

You went to heaven

And there plucked a strange and beautiful flower

And what if

When you awoke

You had that flower in your hand

Ah, what then?

In 2004, two anthologies were devoted to the relationship of modern poets with the pre-Hispanic legacy: El corazón prestado (The borrowed heart), by Víctor Manuel Mendiola, and Un pasado visible (A visible past), by Gustavo Jiménez Aguirre.

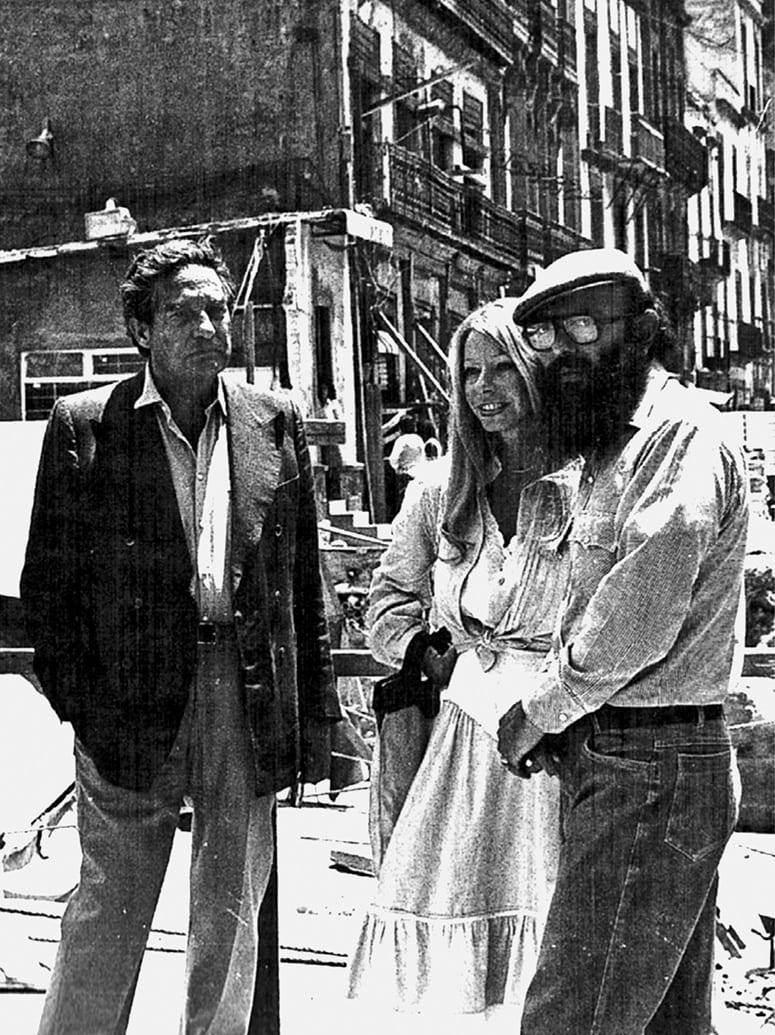

Eduardo Matos Moctezuma with Octavio and Marie-Jo Paz at the Templo Mayor excavation site in the center of Mexico City, around 1981. Photo: Salvador Guilliem Arroyo

It’s difficult to imagine what that approach would have been without the passionate reflections of Octavio Paz, a dominant figure among Mexican intellectuals during the second half of the twentieth century. In addition to his luminous essays on art and the conception of the ancient world, Paz dedicated his greatest poem to the Aztec calendar in 1957. Piedra de sol (Sunstone, 1987) includes 584 hendecasyllables; the verses add up to complete a cycle, the “binding of the years” that governs Aztec time. A multilayered poem about love, eroticism, nature, the condition of the individual before the vicissitudes of history, and the incessant flow of time, Sunstone is also a search for identity. The self is a lost being that can only recognize himself in others: “all the others that we are”—“los otros todos que nosotros somos.” The poem begins and ends with the same verses, imitating the circular flow of the myth. Eduardo Matos Moctezuma notices, in the poem, a recreation of the Aztec mentality marked by the complementary forces of creation and destruction, a “dialectical conception of the universe that is expressed through duality and constant change.”

While Octavio Paz forged decisive pathways in the modern discussion of the past, the main link with indigenous writing was Nezahualcoyotl, a fifteenth-century poet who ruled Tetzcoco for 40 years. About 30 of his poems survive. Those words are a portal that does not exhaust its mysteries, a threshold that seems to vanish as we cross it. Is the unprecedented modernity of his ideas true to what he thought? Or has it been reformulated by the whims of his translators and interpreters? We can only guess.

The historian Miguel León-Portilla (1926–2019) considers Nezahualcoyotl the first humanist of the New World. An enlightened, hedonistic, peaceful ruler in an environment of sacred warfare, the poet-king adored nature. He erected a temple to the war god, Huitzilopochtli, in recognition of Aztec hegemony, but across from it he raised another effigy in honor of Tloque Nahuaque, the Unknown God, Lord of the Near and the Nigh, a being without face or figure, represented by crossbars symbolizing the levels of heaven. This invisible, metaphysical deity pays tribute to the ineffable.

In his verses, Nezahualcoyotl traverses all the registers of the Nahua tradition of “flower and song.” If human sacrifices were accepted as a sacred tribute imposed by the priest-rulers, poetry was their rebellious other side. In a context accustomed to offering life to quench the thirst of the gods, Nezahualcoyotl asks, “Do we really live rooted in the earth?” adding sadly, “Like a painting / we will fade away.” In frank opposition to this destiny, he proclaims: “There, where death does not exist, / there where it is conquered, / there go I.”

The poet-king conceives Tloque Nahuaque, the Unknown God, as an author who traces the codex of human life—“with songs you give shade / to those who must live on earth”—and remedies it like a perpetual eraser—“with black ink you will blot out / all that was brotherhood.” Nezahualcoyotl deciphers enigmas while he is deciphered by a god. Centuries later, Octavio Paz would say, “I too am written, at this very moment someone spells me out.”

In his book Tríptico de la muerte (Triptych of death, 2015), Eduardo Matos Moctezuma includes a selection of Nahua poetry, translated by Ángel María Garibay (1892–1967), that provides a sound echo to Nezahualcoyotl’s verses. Matos writes, “Ideology conditions the places where dead individuals will go and reserves the best fate for the warriors, who are necessary for the survival of Tenochtitlan.” Poetry, however, does not fully conform to that fate. In a severely guarded environment, subjected to strict religious domination, the anonymous authors protest against their fleeting passage on earth: “Anyone who prays to God / jeopardizes his destiny by surrendering it.” The lament continues in several poems: “I cry, I grieve when I remember / that we will leave behind beautiful flowers, beautiful songs.” “We must leave the earth that endures.” “To oblivion and vapor I must surrender myself.”

Nezahualcoyotl challenged the transience of all things through words: “My flowers will not wilt / my songs will not cease.”

Human life, inherently brief, was exposed to the edge of the obsidian blade that extracted hearts on the sacrificial stone. The “flower and song” poems are the result of an intellectual uprising; they do not meekly accept the idea that dead warriors accompany the sun, or console themselves by thinking of underworld abodes; they question the mandate of dying and they celebrate nature as the supreme form of life. Nezahualcoyotl challenged the transience of all things through words: “My flowers will not wilt / my songs will not cease.”

Carlos Pellicer (1897–1977), a Catholic poet who was passionate about archaeology, created the La Venta Museum in Tabasco to safeguard Olmec culture. The space itself defined its content: an enclosure made of wood and plants in dialogue with the surrounding flora. It is no coincidence that Pellicer dedicated an extensive poem to Nezahualcoyotl, focused on his sensual dealings with the biosphere:

Y es que había muchas flores en su cuerpo.

El Dios Desconocido, fue sólo para él.

Enorme intimidad a la intemperie.

La voz entera, a solas.

La voz eléctrica en el páramo

de cualquier soledad a media noche.

El esférico ámbito de la revelación.

El terror saludable de estar vivo

frente a Dios.There were many flowers on his body.

The Unknown God, he was only for him.

Vast intimacy out in the open.

The whole voice, alone.

The electric voice in the wasteland

of any midnight loneliness.

The spherical realm of revelation.

The healthy terror of being alive

before God.

Amid the disorders of intelligence—the inevitable result of “progress”—Pellicer sought the flowers that still sprout among the ancient stones of the pyramids, like messages from Nezahualcoyotl. In today’s pandemic times, one verse is strikingly relevant: “The healthy terror of being alive.” Global warming and the acceleration of ecocide give renewed importance both to the poetry of the poet-king of Tetzcoco and to Carlos Pellicer’s interpretation of him.

Poems that seek to capture the essence of archaeological sites abound. Efraín Bartolomé visited Toniná; José Emilio Pacheco visited Tulum; Jaime García Terrés (1924–1996) visited Yaxchilán; Efraín Huerta (1914–1982) visited Tajín. José Carlos Becerra (1936–1970) said of those places that “nothing rests but everything sleeps.” The stones speak through the language of dreams.

Among the poets who have touched on the mystery of the sleeping stones, Rubén Bonifaz Nuño (1923–2013) stands out. Bonifaz Nuño was a connoisseur of pre-Hispanic culture, and dedicated several essays to the topic. In his poetry, he sought an original entrée to that universe. Bonifaz Nuño avoids the obvious allusions to the past. He doesn’t mention, for example, heroes, archaeological sites, or deities. He seeks an intimate, everyday understanding, a contact with otherness, which is strangely natural. In the present, the poet takes ownership of the aesthetics of that era. With an economy of resources equivalent to that of the “flower and song” tradition, he covers the same issues, the fleetingness of life, the feeling of being on borrowed land, and the intimate rebellion against that fate, but he lends them the tone and cadence of modern poetry:

Amigos, era cierto;

nada tenemos nunca para siempre.

El morir procuramos, con tan sólo

querer el otro día.. . .

Nos miramos

Apenas un instante, en el florido

encuentro de los rostros,

y echados somos de la fiesta

antes de tiempo siempre, y sin remedio.. . .

Porque todo es prestado; se nos prestan

la casa, el despertar, la compañía,. . .

Y que nadie me llame en esta hora

En que, tal vez, me esperas.

Friends, it was true;

we never have anything forever.

By willing the next day to dawn,

we seek death.. . .

We gaze at each other

for an instant, in the flowery

encounter of faces,

and we are thrown out of the party

always too early, and without a fix.. . .

Because everything is borrowed,

our houses, our awakenings, our company,. . .

Let nobody call on me at this hour

when, perhaps, you’ll be expecting me.

Bonifaz Nuño wrote novel poems with an ancestral substratum. The essential themes of Nahuatl poetry are present (the destiny one cannot escape, the transience of all things, the moment that is treasured like a flower sprouting), but they are recovered with the simplicity of contemporary language. The distant acquires intimacy; Bonifaz Nuño adds the second person singular (tú) to the “flower and song” tradition. The poet is not speaking to someone far away, emerging across centuries, but to someone who could be by his side: “Let nobody call on me at this hour / when, perhaps, you’ll be expecting me.”

This method of composition is reminiscent of one of the most disputed questions in archaeology: whether to reconstruct or consolidate discoveries. For a long time, the idea of rebuilding the pyramids prevailed, which was done in Teotihuacan and Cholula. With a sense of humor, Eduardo Matos Moctezuma has pointed out that this practice reveals Toltec influence—not that of the inhabitants of the archaeological site of Tula, but that of a Mexican cement company called Cementos Tolteca. Counter to this idea of architecturally reconstructing the past, Matos proposed an archaeology that not only preserves the stones, but also their historicity, that is, the state in which they were found. This stance reached a critical moment with the discovery of the Templo Mayor in 1978. The architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez (1919–2013), creator of the National Museum of Anthropology, proposed the recreation of the dual temple of the Aztecs. President José López Portillo (1920–2004), who had written a book on Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent, and felt like a modern Aztec emperor, listened sympathetically to the architect. But Matos sidestepped the nonsense of turning the historical site into a theme park, arguing that the discovery should honor a bygone culture, but should also show how it had been destroyed. By consolidating rather than reconstructing findings, archaeology allows us to observe various layers of time. Rather than artificially restoring the former appearance of buildings, they are recovered without disguising the wounds of time.

Eduardo Matos Moctezuma pointing out the excavated remains and reconstructed building stages in this cutaway model at the onsite Museo Templo Mayor, Mexico City. Photo: Ryan Christopher Jones

Bonifaz Nuño works in a similar fashion in his poetry. Through everyday words that are accessible to the contemporary reader, he opens a window to a remote zone of time. What he communicates is both archaic and recent—a broken world that can be seen naturally from the present, which has not stopped resembling its previous iteration and perhaps will suffer the same fate. The poet speaks of the “borrowed heart” that humans carry and of which they are never entirely the owners. This dilemma could easily refer to a warrior on the sacrificial stone or to any of us subject to the tribulations of feelings.

What fate has poetry found in the more than 60 native languages spoken in Mexico? The restitution of the voices of “flower and song” owes much to the work of Father Ángel María Garibay, who also translated classical Greek and Hebrew. At the end of the twentieth century, this toil of recovery found a notable follower in Carlos Monte-mayor (1947–2010), who had also been trained in classical languages. After the Zapatista rebellion, Montemayor’s academic zeal took on political significance. His interest in vernacular languages spread to those who express their emotions in those languages today. Departing from his archival research, he created new literary workshops, and “dead” languages were resurrected in several anthologies.

Despite contributions such as Montemayor’s, Mexico continues to discriminate against native languages, several of which are in danger of extinction.

Despite contributions such as Montemayor’s, Mexico continues to discriminate against native languages, several of which are in danger of extinction. Poet and essayist Gabriel Zaid points out a dramatic example: the Paipai community, a Baja California people who have raised remarkable poetic songs to the sun, had only 216 members left in 2015. Although there are well-known Nahua authors, such as Natalio Hernández and Mardonio Carballo, and Zapotecs such as Irma Pineda and Natalia Toledo, there is still a long way to go for that universe to occupy the place it deserves in our culture.

Víctor de la Cruz Pérez (1948–2015), a poet from Juchitán, Oaxaca, knew that his voice could fall into an abyss. In the poem “Who are we? What is our name?” he ponders the meaning of writing in an imposed, radically distant environment. His verses strike with the force of what “should not be there” and yet appears:

¿Con quién hablar, qué decir

si no hay nadie en esta casa

y tan sólo oigo el gemir del grillo?

Si digo sí, si digo no,

¿a quién digo sí, a quién digo no?

¿De dónde salió este no y este sí

y con quién hablo en medio de esta obscuridad?

¿Quién puso estas palabras sobre el papel?

¿Por qué se escribe sobre el papel

en vez de escribir sobre la tierra?Whom to talk to, and what to say,

when there is no one home

and the chirping of the cricket is all I hear?

If I say yes, if I say no,

to whom do I say yes? To whom do I say no?

Where did they come from, this no and this yes,

and whom do I address in the midst of this darkness?

Who put these words to paper?

Why do we write on paper,

and not on the earth?

Contemporary poetry in vernacular languages is practiced in a threatened realm where to write is to safeguard. Juventino Gutiérrez Gómez, a Mixe poet from Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca, born in 1985, describes this task in a poem that bears the eloquent title “Guarida” (Lair):

Cuando los animales

recogen sus cuerdas vocales

de los árboles,

de los tejados,

de los maizales:

están guardando

mi lenguaje.When the animals

gather up their vocal cords

from the trees,

from the rooftops,

from the cornfields:

they are safeguarding

my language.

The obsidian mirror in which Quetzalcoatl saw himself still has duties to fulfill. This essay, written to recreate the dialogue between archaeology and literature, and to pay tribute to one of the greatest champions of that conversation, Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, attempts to show that the ancient world, which for centuries was seen as something that had passed and was shuttered, remains open. Time is not stationary. Through archaeology, the origin stones return to us; through literature, they speak to us again.

August 13, 2021, marks five hundred years since the fall of Tenochtitlan. The challenge of inclusion continues to be a pending issue in Mexico’s unequal society. In his own literary Sunstone, Octavio Paz alludes to a yet future community: “all the others that we are”—“los otros todos que nosotros somos.” Our perception of ourselves depends on what is “other,” to the same extent that the future is nourished by another era.

The future of the past is yet to come.

Juan Villoro is a writer and journalist living in Mexico City. He presented this essay in Harvard’s Eduardo Matos Moctezuma Lecture Series on October 15, 2020. This is the first lecture series in Harvard’s history to be named after a Mexican. Following Davíd Carrasco’s initiative, the series is sponsored by the Divinity School, the Moses Mesoamerican Archive and Research Project, the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, and the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, with generous support from José Antonio Alonso Espinosa and Karen Beckmann. The author wishes to thank Erin Goodman for her English translation and Scott Sessions for his editorial work. An expanded and richly illustrated version of the original Spanish text appears in Arqueología Mexicana, special issue 95 (February 2021): 12–89.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.