A Look Back

The Fall of the Family

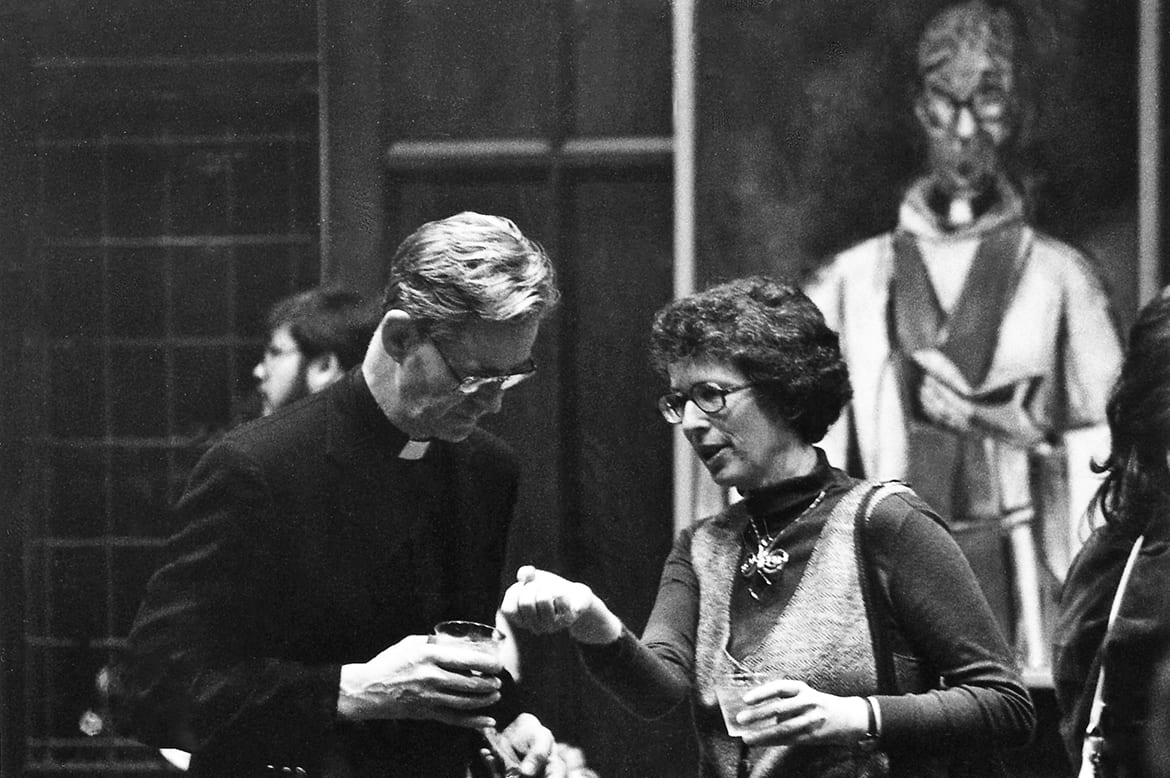

Krister Stendahl and Clarissa Atkinson, 1984. HDS photograph

By Clarissa W. Atkinson

I believe that the most pervasive and important myth attached to the American family is the myth of a Fall. The story is familiar, for it begins in a garden, where we lived in harmony, without single parents or latchkey children or the marriage tax. Before the Fall, many kindly adults were available to care for children, who played in unpolluted meadows far from toxic waste dumps. . . . These children . . . learned the basics in neighborhood schools, and they learned to work beside their parents in fields and shops and kitchens. When they grew up, they moved down the street, or possibly into the next county, but they came home for Thanksgiving and Christmas, and whenever there was trouble or something to celebrate. In those days, . . . the suicide rate did not surge during the holiday season. This was before Christmas was contaminated by Mastercharge, by Hallmark and Sears and G.E.—who make good things for people. . . . Everybody had a family in those days, and it worked. . . .

Depending on your point of view, the family worked because in those days it was a unit of production, not a unit of consumption. Or it worked because divorce wasn’t easy to arrange, because people didn’t move halfway across the country. Mothers helped . . . daughters to take care of the baby; children didn’t watch violence on TV; people went to church together and obeyed God’s laws for families. . . . Without efficient and accessible contraceptives, parents saw to it that their daughters, if not their sons, were virgins when they married. Abortion . . . happened to other people’s daughters and in other people’s neighborhoods. There were no homosexuals, and if there had been, they would not have been married in church. . . . Artificial insemination was for cows. Test-tube babies were for science fiction. God sent babies to people who deserved them, and they required neither nursery school nor orthodontia nor car pools to hockey practice at 5 am.

Our versions of family life before the Fall differ a bit, depending on what we think is most wrong about the present. But most of us agree that it happened, even if we’re not sure why, or when. Some say the family Fell with the Industrial Revolution, when Father left home for the office or the mill. Some say it happened in the 1920’s, when women began to cut their hair and drink gin. And some of us locate the Fall in our own memories, along about the time the Beatles landed, and kids took to the streets to tell their elders what to do. Whenever it began, it was cataclysmic. The American Family was driven out of Eden. . . . We have not been back to the Garden since, although lately, some say, there is hope. If we stop coddling our young, stop everybody from indulging in sex outside of marriage, and stop expecting the government to care for our elderly, sick, or unemployed relations, we may build an Ark. Certainly we will enter it two by two.

. . . Family structure and family values are the building blocks of civilization, and building blocks—by definition—are solid and unchanging. The American Family was (wasn’t it?) the institution through which, along with the public schools, we learned to be virtuous. Rich and poor, black and white, Christian and Jewish, immigrant and native-born, inside the household we were all parents and children, brothers and sisters, husbands and wives. . . .

As a nostalgic American, reader of newspapers, and mother of three young adults, I agree wholeheartedly that things are not what they were. As a historian, however, I have to observe that they never were. Our Family in the Garden has the truth of myth, but not of history. And as a critic of patriarchy, and even of the American Dream, I must notice that the myth is sometimes harmful as well as deceptive. If we really look at the past, we soon discover that there never was an eternal Family. Domestic values have always changed and developed along with society and technology. Long before the modern era, the so-called private sphere was moving right along with business and war and politics and culture; these things change continually, and they change in relation to one another. It may be comforting to believe that there was a time when personal lives and family relationships were stable, but the fact is that we cannot locate such a time in the past any more than we can in the present. And in the end, it may be more comforting to realize that this is not necessarily the worst of times, that human beings have weathered periods of upheaval before now, even upheaval in their cherished homes and their ways of living together.

Clarissa W. Atkinson served as associate dean for academic affairs at HDS from 1987 to 2000, and was Assistant Professor of History of Christianity from 1980 to 1987. Previously, she was a research associate in church history and women’s studies at HDS (1974–76).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.