Featured

Teffi, Rasputin, and the Revolution

Searching for the Russian soul, a century later.

The Nativity Cathedral and the Wooden Church of St. Nicholas, Suzdal, Russia. Photo by Randy Rosenthal

By Randy Rosenthal

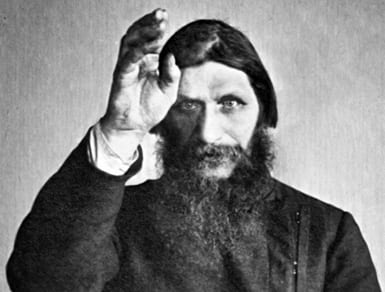

In early 1905, a mysterious peasant from Siberia arrived in St. Petersburg. It was said he could tell your past and future simply by looking at your face. Many believed his words could heal and give protection. There was something about his eyes, everyone agreed, that pierced like needles. He spoke of God and love. His name was Grigory Rasputin, and he is one of the most fascinating characters in history.

The Russian gentry of the time were mad about peasant holy men and the occult, and Rasputin was brought to the city’s salons and introduced to the noblest families. Within a year, he went from the bottom of society to the top. He won the trust of the tsar and tsarina—by mysteriously healing their hemophiliac son, Alexei—and began making regular visits to the imperial palace, becoming their spiritual adviser. The royal couple referred to him as a starets—an elder of a Russian Orthodox monastery—even though he was only thirty-six, married, and had never taken holy orders. But most husbands and members of the clergy hated Rasputin, who had a peculiar habit of giving women big hugs and wet kisses, something that was just not done in Petersburg circles. And he addressed everyone, regardless of social status, using the informal ty. By 1910, when the press broke the first scandals about him, everyone in Russia knew his name. By 1915, there were signs above dining room fireplaces that read: “In this house we do not talk about Rasputin.”

Rasputin, ca. 1914

In the years leading up to the revolution, Rasputin so dominated Russian culture that members of the press reported his daily comings and goings as if he were the tsar. They spread rumors that people repeated as fact: As a youth Rasputin stole horses and set fires. He had raped nuns in a convent. He was spying for the Germans. He was in league with the masons. He was working for “international Jewry” in their secret plot to destroy Christian Russia. He was raiding the royal treasury through theft and graft and corruption. He was a khlyst—a member of an extreme religious sect said to sing and whirl about in circles and then cut off the breast of a naked virgin and collectively eat it, before falling to the ground and engaging in group sex. He could keep an erection for hours, pleasuring one woman after another with his enormous member. He was screwing the tsarina. He was the actual father of the tsarevich. He controlled the tsar with oriental drugs. They said Rasputin was a sorcerer. That he was the antichrist. The very incarnation of evil.

Nobody knew if these rumors were true, but nearly everybody believed them. And because the Russian people believed Tsar Nicholas II allowed a depraved peasant to run their country, they lost faith in the divine authority of the royal family—and the five-hundred-year-old system collapsed. So, to me, Rasputin played as big a role in the Russian Revolution as Lenin.

About a hundred years after the Bolsheviks seized power, I went to Russia and brought along Douglas Smith’s bible-sized biography Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs, as well as a couple of books by a Russian author I’d never heard of before, but who was a celebrity at the time of the revolution: Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya, better known by her pen name Teffi.

When people asked why I was going to Russia, I wasn’t sure what to say. Yes, I knew Russians had the reputation of being homophobic xenophobes who don’t respect human rights or the international rule of law. But I was feeling the travel itch, and I’m interested in holy places. So when my Russian friend Galina offered to guide me around Russia’s Golden Ring and then the Crimea, I said, why not.

The Golden Ring is a group of eight old cities northeast of Moscow that played a crucial role both in the formation of the Russian Orthodox Church and of Russia itself. They were cultural centers and trading capitals when Moscow was just a bunch of cowsheds. They’re called a ring because, geographically, they form an oval, and golden because they’re crowded with a ridiculous number of golden-domed churches, cathedrals, kremlins, and monasteries.

Some of these fairytale towns, like Suzdal, are referred to as “open-air museums” for their abundance of unspoiled, medieval Russian architecture. Others, like Vladimir, were swallowed up by industrial Soviet sprawl. With its Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius—the large monastery and spiritual home of Russian Orthodoxy—Sergiyev Posad remains the most important Golden Ring city, and Rostov Velikiy is the oldest. On the train from the former to the latter, I read Teffi’s collection of autobiographical stories, Tolstoy, Rasputin, Others, and Me.

When Teffi was thirteen, she met Tolstoy. She had been reading War and Peace and became very upset when Prince Andrei died. So she decided to go and see Tolstoy at his house in Moscow to ask him to save Prince Andrei’s life. She worked out where Tolstoy lived by asking around and got a photograph of the author for him to sign, as a pretense for her visit. Then, when her household was distracted with visitors, she had her elderly nanny walk her over to Tolstoy’s house.

Because she was from a respectable family, they were let inside. But once in the count’s foyer, Teffi panicked. All she wanted was to leave. When Tolstoy appeared—he was shorter than she expected—she meekly held out her photograph and in a little girl’s voice she asked, “Would you pwease sign your photogwaph?”1 This was in 1885, when Tolstoy was fifty-seven and had already written his masterpieces. He was probably working on The Death of Ivan Ilyich when Teffi interrupted him. But Tolstoy, the good sport, took the photograph to his office and she, unbearably ashamed, realized she couldn’t possibly ask him for anything else. Unable to admit why she had actually come, she only curtsied when he handed her back the signed photo. Tolstoy then turned to the nanny and asked what he could do for her. But the old maid replied she was just there with the young lady. In bed later than night, Teffi cried into her pillow, remembering her “pwease” and “photogwaph.” That was that. Her meeting with the great author was a failure, though it’s lovely to think that at one time a girl could simply walk over to Tolstoy’s house and ask him for an autograph.

Years later, when Teffi was a relatively famous writer herself, a young actress in one of her plays approached during rehearsal and asked if Teffi could prevent a poor boy in the story from being fired. Why did Teffi have to be so cruel to the boy? Couldn’t she change it and put things right? She’s the author, after all. But by then Teffi knew that writers have no choice in the matter. “I don’t know,” Teffi replied, “I can’t. It’s not me who decides.”2 If the thirteen-year-old Teffi had managed to ask Tolstoy to save Prince Andrei, he might have answered similarly. It’s not authors who decide.

Teffi also met Rasputin, twice. This was during the First World War, when all kinds of crazy rumors were circulating about him. “In that atmosphere of hysteria,” Teffi wrote, “even the most idiotic flight of fancy seemed plausible,” such as people believing that Rasputin was directing the country’s military strategy through prayer and hypnotic suggestion. An editor invited Teffi to a dinner that Rasputin would attend, with the hope that she’d get him to talk about “erotic matters.” She was hesitant, but also curious to meet him. To her, Rasputin wasn’t just someone who would be in the history books but was “unique, one of a kind, like a character out of a novel,” someone who “lived in legend.”3

Teffi in Petersburg, 1915. Courtesy of Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscripts Library, Bakhmeteff Archive, the Nadezhda Teffi papers.

So she went to the dinner, and I’m glad she did. I feel I’ve come to know Rasputin more from reading Teffi’s little chapter than through the seven hundred pages of Smith’s biography. Such is the power of literary talent. Not only did Teffi see Rasputin in action, she saw through him. He was simply posturing, she thought. Playing the role of the holy peasant. Distracted and twitchy, he was drinking a great deal, and very quickly. He tried to get her drunk, telling her that God would forgive her for drinking. She said she didn’t care for wine. “Nonsense!” Rasputin replied. “Drink. I’m telling you: God will forgive you,” he said. “God will forgive you many things. Drink!”

He also wanted her to come to his house after dinner. Despite his insistent invitations, she said she wouldn’t go. She wouldn’t play his game. Calling her “a stubborn one,” he quickly and quietly reached out and touched her shoulder, “like a hypnotist using touch to direct the current of his will.” But, with Teffi, his will met resistance. It couldn’t penetrate her, and so it shot back to him. Every time he touched her, his body shook with a spasm and he uttered a groan of physical pain. He was unable to dominate her, as he did the tsarina and so many ladies-in-waiting. Teffi even laughed at him. “You may be laughing,” he told her. “But do you know what your eyes are saying? Your eyes are sad.” This got her attention. “Don’t you know we all love sweet tears,” he continued, “a woman’s sweet tears?”

“I know everything,” he told her. She asked him what he knew. “I know how love can make one person force another to suffer. And I know how necessary it can be to make someone suffer. But I don’t want you to suffer. Understand?”

She didn’t understand. She thought much of what he said was delirious babble. “God . . . prayer . . . wine,” he kept repeating. But she admitted Rasputin was truly out of the ordinary, and she agreed to go to a second dinner where he’d be. By the end of that evening, Teffi knew this wasn’t a straightforward business at all. Rasputin wasn’t what people said he was, neither the haters nor the lovers. “Howling inside him was a black beast,” Teffi observed. Someone started playing music and Rasputin got up to dance. And when he danced, circling round and round, his face tense and bewildered, his movement frenzied, “the spectacle was so weird, so wild, that it made you want to let out a howl and hurl yourself into the circle, to leap and whirl alongside him for as long as you had the strength.” Such was his power, his intoxicating personality. For a moment she was a believer.

But when he stopped dancing, Teffi said Rasputin appeared completely mad. He stood still in the middle of the room “thin and black—a gnarled tree, withered and scorched.”4 His death would be the end of Russia, he told her. Before they parted, he prophesized he would be killed and said his murder would bring the downfall of the empire. And it did.

But was it the end of Russia? Yes, and no. Because Rasputin not only symbolizes what Russia was, but what it still is: its passion and obsession with mysticism, its irrationality and disregard for logic, its deep superstitions, its religion without morality, its faith without works, its surrender to sud’ba—fate.

To Teffi’s friend Vasily Rozanov, the writer and philosopher who joined her at these dinners, Rasputin represented “an incarnation of Old Rus’, pre-Petrine Russia, before the adoption of European ideas, habits, technology,” what Rozanov called shtunda—the German discipline, self-control, and cleanliness that Peter the Great introduced in the early eighteenth century. The neat and tidy and boring and dead. To Rozanov, Rasputin’s “mysterious electricity” embodied the essence of religion. He was holiness manifested in its ancient Slavic form.5

Teffi got married when she was eighteen. She had a child soon after. Less than a decade later, she abandoned her family to pursue a writing career in St. Petersburg. When he arrived in Petersburg, Rasputin, too, had left a wife and three children back in Siberia. And like any peasant, he had a farm and livestock to take care of. But when he was twenty-eight and had been married for ten years, Rasputin left all of his responsibilities behind and became a strannik, a holy wanderer.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, undertaking pilgrimages to holy places was seen as a way to salvation, and stranniki were a common sight in old Russia. There were about a million of them in 1900, wandering from one holy place to another, living off the generosity of strangers, and repeating the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

As a pilgrim, Rasputin walked thirty miles a day in all kinds of weather. He went days without food or water. For six months he wandered without changing his underclothes. For three years he traveled in fetters, the chains of the Holy Fool. When bandits robbed him, he surprised them by giving them everything he had. “It’s not mine,” he told them, “it’s God’s.”6 By the time he decided to go to Petersburg, it was said that Rasputin had acquired his gift of prophecy through his years of fasting and prayer. Many people said Rasputin was illiterate, but, while wandering, he learned to read and write, albeit with difficulty and atrocious spelling. He published a few books during his lifetime, and it’s his own words that offer the best glimpse into his mind.

He mostly thought of love. While visiting Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher, Rasputin wrote in a notebook: “I felt that the Sepulcher is the tomb of love and this was such a strong feeling that I was ready to hug everyone and felt such love toward people that everyone seemed to be a holy man because love does not allow you to see people’s weaknesses.”7 He wasn’t talking about the easy love one has for God, but the difficult, messy love one person has for another: “Love is great suffering, it doesn’t let you eat, it doesn’t let you sleep. It is mixed with sin. Still it is better to love. A person makes mistakes in love and suffers from them, and his suffering purges his mistakes.”

“Love is everything,” Rasputin wrote, “love will protect you from a bullet.”8 And, according to legend, Rasputin was poisoned and shot three times—but poison and bullets didn’t kill him. He only died when he was thrown into the icy Neva, and drowned.9

Once St. Petersburg fell to the Bolsheviks in October 1917, everyone knew it was only a matter of time before the revolutionaries reached Moscow, where Teffi was living. So when she was offered an opportunity to travel to Kiev and Odessa, she took it. The plan was to stay in Ukraine for a month and give public readings and then return to Russia. She never went back.

As she traveled from Moscow to the Black Sea, she stayed one step ahead of the Reds, and reading her memoir, Memories, entirely changed my understanding of the situation. Teffi’s experience makes it clear that the Bolshevik Revolution wasn’t an ideological struggle about Marxism. Sure, Lenin and Trotsky and some of the intelligentsia might have been motivated by ideology. But it’s not the intelligentsia who make a revolution, it’s the people. And by Teffi’s account, the people were motivated by envy, resentment, and revenge.

By the time I left the Crimea, I understood that the allure of Rasputin lies in the mystery surrounding him.

On the train leaving Moscow, passengers looked at Teffi and her traveling companions with “real fury—the intelligentsia suspecting we might be from the Cheka while the workers and peasants saw us as capitalist landlords still drinking their blood.” Members of the bourgeoisie fled with diamonds stuffed into hollowed-out sticks and teapots with false bottoms. One lady even tried to smuggle a diamond in a hard-boiled egg, only to see a Red Army soldier snatch the egg and wolf it down. Teffi’s friend was harassed by two “malicious-looking peasant women,” who loudly exclaimed: “Lynch every one of ’em! . . . Poke out their eyes, rip out their tongues, cut off their ears, and then tie a stone round their necks and—into the water with ’em!” Everywhere she felt the “people’s wrath.”10

In her essay “The Gadarene Swine,” Teffi writes that everybody, rich and poor, was running from the “men possessed by demons who came out from the tombs.”11 The rich “swine” were running in order to save Russian culture—and obviously their money. But the meek “sheep” were also running, which embarrassed the Bolsheviks. Because why would the poor run from those who profess to be serving the poor? “The crazed swine are escaping the Bolshevik truth, from socialist principles, from equality and justice,” Teffi writes, “while the meek and frightened are escaping from untruth, from Bolshevism’s black reality, from terror, injustice and violence.”12

At the makeshift border between Russia and Ukraine, a twenty-five-mile zone of bribery, robbery, and chaos, Teffi and crew were forced to stay in a Bolshevik-controlled village and put on a play for soldiers of the Red Army. (Teffi was so famous she was loved by both Lenin and the tsar.) The self-proclaimed “arts commissioner” of the village wore a long beaver coat with a small round hole in the back; the hole was surrounded by the dried blood of whomever he stole the coat from. Everywhere, there was talk of people being strangled and shot, of robbery and looting. That’s what the revolution was to Teffi—an excuse for theft. (Around this time, even Lenin was robbed at gunpoint in Petersburg, by comrades who didn’t recognize him.) As Teffi escaped into Ukraine, it seemed to her that the “Red Army” was controlled by thug brigands—riffraff coming to power, after centuries of being exploited.

For a while, Teffi enjoyed a cultural explosion in Kiev. Occupied by the Germans, the city was a haven for Russian artists and intellectuals. There, she felt the peace of mind that comes from having an abundance of food, of being “confident that nobody—nobody whatsoever—was intending to have us shot.”13 But the Germans withdrew, and an armed band of peasants led by Ukrainian nationalist Symon Petliura chased the refugees out of the city. Teffi moved on to French-occupied Odessa, where gangs had taken over the abandoned quarries that formed catacombs under the city. They slowly robbed the exiles of all they had. Notorious gangsters like “Mishka the Japanese” stopped cabs on the way home from theaters and clubs, stealing watches hidden in shoes and rings hidden in cheeks. But it was the gangs from within Moldavanka—the Jewish ghetto of Odessa, which Isaac Babel made famous in his Odessa Tales—who began outright looting the bourgeoisie and foreigners. Once the French troops left the city, these “bolsheviks” came out of hiding and chased Teffi further “down the map” and into the Black Sea.

By then, she was tired of it all. “Everything had become boring, boring to the point of revulsion. It was all just coarse, dirty, and stupid.”14 The cold, the hunger, the darkness, the rifle butts banging on floors. She was tired of hearing screams, weeping, and gunshots. She was tired of the death of others—that’s what she was most afraid of, not her own death, not death itself, but of “blind mindless rage.” And so, pushed by “a groundswell of tension—ripples and echoes from a storm that was raging more fiercely elsewhere,” she boarded a ship with a motor that only ran in reverse, and was tugged into the Black Sea, her “new road into the unknown, dark and calm.”15

After eight days at sea—or ten, who knew?—Teffi arrived in the Crimea. She found Sevastopol “dusty, dismal, shabby.” (I could say the same for Simferopol, where I landed while reading about Teffi’s journey.) She couldn’t complain too much, since the city was still held by the anti-Bolshevik White Army. She quickly moved on to Novorossiysk and the White capital of Yekaterinodar, where she stayed a while before finally saying goodbye to Russia and going abroad, first to Constantinople and then to Paris, where she’d live for the rest of her life, writing about the past—frozen, like Lot’s wife, for looking back, “turned into a pillar of salt forever.”16

Rasputin too, was forced to the Black Sea. In February 1911, as the first wave of scandals against him were reaching their crest in the press, the tsar ordered Rasputin to go on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. And so, like Teffi would do seven years later, Rasputin journeyed to Kiev and then to Odessa, where he joined some six hundred other Russian pilgrims on a steamer bound for Constantinople, and on to Jerusalem. It was Rasputin’s first time at sea, and he found the experience amazing. In his journal he wrote:

The sea consoles you without any effort. When you wake up in the morning, the waves are talking and splashing and making you happy. And the sun shines in the sea, and slowly rises, and the human soul forgets everything at that moment and looks at the glimmering sun and the soul starts rejoicing and the person feels like he is reading the book of life—an indescribable picture! The sea wakes you from the sleep of vanities. . . . we look at God’s nature and praise God and his Creation and the beauty of nature, which cannot be described by any human mind or philosophy.17

I read these words on the beach in the ancient Crimean city of Sudak, before going for a swim in the Black Sea. And by the time I left the Crimea, I understood that the allure of Rasputin lies in the mystery surrounding him—the mythology that enshrouds the truth of his story. Yes, Rasputin was a big drinker, and he did take lovers and visit prostitutes. He did have the habit of publicly kissing women on the mouth, and stroking their arms and shoulders, if not more of their bodies—his “creepy petting,” as Smith calls it. But otherwise, nearly nothing that was said about Rasputin was true.

Despite great effort to find proof that he was a spy, a traitor, a khlyst, a thief, a hypnotist, and that he was screwing the empress, no proof was ever found. All that was found were blatant lies and rumors. To the narod—the Russian people—“Rasputin had become the symbol of an omnipotent and irresponsible government that led Russia to ruin.”18 The people lost faith in the divine authority of the monarchy because of a fantasy created by the press. Because one thing was beyond doubt: Rasputin sold newspapers.

And to the educated, Western-leaning aristocrats, Rasputin was not only a symbol of absurd Russian mysticism and irrationality, of Russia’s “backwardness,” but of the imminent loss of their social privilege. To them, he was just a peasant. And to have a peasant in the midst of high-society—not to mention fondling aristocratic women in the salons of the imperial capital—was, as Smith writes, “an outrage, an inversion of the natural order of things, a sign of utter social collapse.”19 By getting rid of Rasputin, they thought they would prevent the oncoming revolution and save Russia. So, early on the morning of December 17, 1916, when Rasputin was forty-seven years old, a few aristocrats got together and murdered him.

Yet to the intelligentsia, Rasputin symbolized every reason why there needed to be a revolution. The Russian Word wrote that Rasputin was “a characteristic leftover of the ‘old order’ of the state when politics was practiced not in state institutions, not under the control of civil rights, but through personal schemes.” In July 1916, Our Workers’ Newspaper wrote that behind Rasputin “hid those secret forces that, given our lack of true European freedom and our lack of a constitution, carry out their work behind the scenes, secretly running the state and directing its ministers, removing them and putting others in their place, and preparing all sorts of reactionary surprises for the country. These secret forces are capable of anything. . . .”20

Here, it’s hard not to see a parallel to Putin’s Russia, where secret forces still carry out their work behind the scenes, and politics is practiced not under the control of civil rights but through personal schemes. The difference is that while the decidedly weak-willed Tsar Nicholas II respected the freedom of press granted in the October Manifesto of 1905, Putin makes no such gestures. And while Nicholas allowed opposition to spread like forest fire, Putin has—so far—successfully put all fires out. Whereas Nicholas wanted to be loved, Putin knows the only thing that matters is to be feared. He understands what Pyotr Stolypin, prime minister of Russia from 1906 through 1911, meant when he warned Nicholas: “In Russia, nothing is more dangerous than the appearance of weakness.”21

To those who believed the rumors about Rasputin, the tsar appeared weak. Russians felt betrayed and abandoned a century ago, and so the Romanovs had to go—regardless of the chaos that would come next.

Notes:

- Tolstoy, Rasputin, Others, and Me: The Best of Teffi, ed. Robert Chandler and Anne Marie Jackson (New York Review of Books Classics, 2016), 168.

- Teffi, Memories: From Moscow to the Black Sea, ed. Edythe Haber (New York Review Books Classics, 2016), 16.

- Tolstoy, Rasputin, Others, and Me, 132, 110.

- Ibid., 125–42.

- Douglas Smith, Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016), 402, 404.

- Ibid., 23.

- The notebook was later published as a book, titled My Thoughts and Reflections.

- Ibid., cited in Smith, Rasputin, 204, 208.

- Smith’s biography disproves the myth surrounding Rasputin’s death: autopsy reports determined he died from a point-blank gunshot to the forehead. There was no water in his lungs. Ibid., 610–11.

- Teffi, Memories, 73.

- Alluding to the exorcism in chapter 8 of the Gospel according to Matthew.

- Tolstoy, Rasputin, Others, and Me, 157.

- Teffi, Memories, 68.

- Ibid., 143.

- Ibid., 139.

- Ibid., 230.

- Smith, Rasputin, 203.

- Ibid., 633.

- Ibid., 391.

- Ibid., 334, 339.

- Ibid., 218.

Randy Rosenthal is the co-founding editor of the literary journals The Coffin Factory and Tweed’s Magazine of Literature & Art. His work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Bookforum, Paris Review Daily, and The New York Journal of Books, among other publications. He is currently studying religion and literature at Harvard Divinity School, is an assistant editor at Harvard Divinity Bulletin, and is a graduate student associate at Harvard’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.