Featured

Spiritual but not Religious

The vital interplay between submission and freedom.

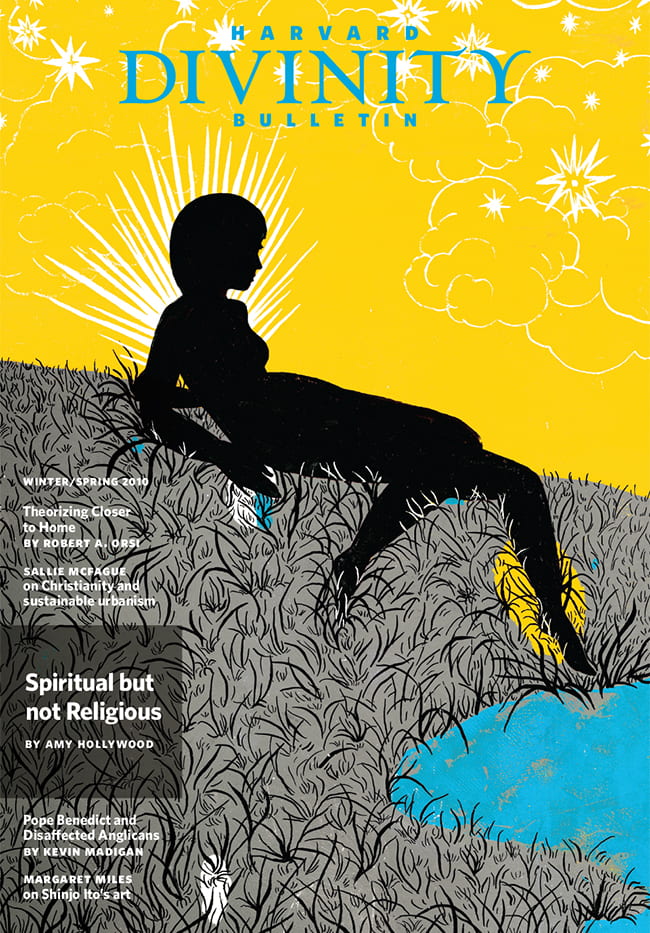

Illustration by Rachel Salomon. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Amy Hollywood

Most of us who write, think, and talk about religion are by now used to hearing people say that they are spiritual, but not religious. With the phrase generally comes the presumption that religion has to do with doctrines, dogmas, and ritual practices, whereas spirituality has to do with the heart, feeling, and experience. The spiritual person has an immediate and spontaneous experience of the divine or of some higher power. She does not subscribe to beliefs handed to her by existing religious traditions, nor does she engage in the ritual life of any particular institution. At the heart of the distinction between religion and spirituality, then, lies the presumption that to think and act within an existing tradition—to practice religion—risks making one less spiritual. To be religious is to bow to the authority of another, to believe in doctrines determined for one in advance, to read ancient texts only as they are handed down through existing interpretative traditions, and blindly to perform formalized rituals. For the spiritual, religion is inert, arid, and dead; the practitioner of religion, whether consciously or not, is at best without feeling, at worst insincere.1

You hear this kind of criticism of religious belief and practice not only among those who call themselves spiritual, but also within religious traditions. For centuries now, Christians have fought over the interplay between authority and tradition, on the one hand, and feeling, enthusiasm, and experience on the other. They have also fought over what kind of experience is properly spiritual or religious. What all sides in these debates share, and what they share with those who understand themselves as spiritual rather than religious, is the presumption that authority and tradition will kill—or, if you are on the other side of the debate, reign in or properly temper—experience. Whereas some American Protestants, for example, insist that one can best know, love, and be saved by God without extraordinary experiences of God’s presence—or with inward experiences rather than with those marked by bodily signs such as tears, shouts, convulsions, outcries, or visions—various revivalist, Holiness, and Pentecostal movements argue that without an intensely felt experience of God, one knows and feels nothing of the divine and so cannot be saved.2

Modern theologians and scholars of religion from Friedrich Schleiermacher and Samuel Taylor Coleridge to William James and his many followers have understood religion itself in terms of experience—and they have also wrestled with the question of what precisely we mean when we talk about religious experience. Yet Wayne Proudfoot and others critical of the emphasis on religious experience in contemporary theology and religious studies argue that what is at stake for Schleiermacher, James, and their heirs is an attempt to identify an independent realm of experience that is irreducible to other forms of experience. This can serve either as a protectionist strategy, whereby the religious person is able to safeguard her religious experience from naturalistic explanations, or as an academic strategy, whereby a realm is posited over which only specialists in religious studies can claim authority.3

Running like a thread throughout all these debates—theological, antitheological, historical, philosophical, and those pursued in the interdisciplinary study of religion—lies the attempt to distinguish true from false, sincere from insincere, supernaturally from naturally caused religious or spiritual experience (the terms may differ, but the general point remains the same). With these distinctions comes the recurrent presumption that genuine religious experience is immediate, spontaneous, personal, and affective and, as such, potentially at odds with religious institutions and their texts, beliefs, and rituals. As a number of scholars of religion—as well as Christian theologians—have recently shown, the danger in these discussions is that they miss the ways in which, for many religious traditions, ancient texts, beliefs, and rituals do not replace experience as the vital center of spiritual life, but instead provide the means for engendering it. At the same time, human experience is the realm within which truth can best be epistemologically and affectively (if we can even separate the two) demonstrated.4

Here I will focus on Christianity, the tradition I know best, and in particular on Christianity in early and medieval Western Europe. Some of the most sophisticated writing about experience in the early and medieval Christian West occurs in works describing and prescribing the best way to live the life of Christian perfection.5 The various forms of monastic life that emerge in the third and fourth centuries of the Common Era all claim to provide the space in which such perfection might be—if not fully attained—most effectively pursued. The monks and nuns who became the self-described spiritual elite of Christianity through at least the high Middle Ages lived under rules that told them what, when, why, where, and how to act. The most successful of these rules in Western Christianity, the sixth-century Rule of Benedict, is often praised for its flexibility and moderation, yet within it the daily lives of the monks are carefully ordered. Written by Benedict of Nursia (ca. 480–550) for his own community, the rule, and variants of it written for the use of women, became the centerpiece of monastic life in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. If ritual is the repeated and formalized practice of particular actions within carefully determined times and places, the moment in which what we believe ought to be the case and what is the case in the messy realm of everyday action come together, then the Benedictine’s life is one in which the monk or nun strives to make every action a ritual action.6

Benedict described the monastery as a “school for the Lord’s service”; the Latin schola is a governing metaphor throughout the rule and was initially used with reference to military schools, ones in which the student is trained in the methods of battle.7 Similarly, Benedict describes the monastery as a training ground for eternal life; the battle to be waged is against the weaknesses of the body and of the spirit. Victory lies in love. For Benedict, through obedience, stability, poverty, and humility—and through the fear, dread, sorrow, and compunction that accompany them—the monk will “quickly arrive at that perfect love of God which casts out fear (1 John 4:18).” Transformed in and into love, “all that [the monk] performed with dread, he will now begin to observe without effort, as though naturally, with habit, no longer out of fear of hell, but out of love for Christ, good habit and delight in virtue.”8

Central to the ritual life of the Benedictine are communal prayer, private reading and devotion, and physical labor. I want to focus here on the first pole of the monastic life, as it is the one that might seem most antithetical to contemporary conceptions of vital and living religious or spiritual experience. Benedict, following John Cassian (ca. 360–430) and other writers on early monasticism, argues that the monk seeks to attain a state of unceasing prayer. Benedict cites Psalm 119: “Seven times a day have I praised you” (verse 164) and “At midnight I arose to give you praise” (verse 62). He therefore calls on his monks to come together eight times a day for the communal recitation of the Psalms and other prayers and readings. Each of the Psalms was recited once a week, with many repeated once or more a day. Benedict provides a detailed schedule for his monks, one in which the biblical injunction always to have a prayer on one’s lips is enacted through the division of the day into the canonical hours.

To many modern ears the repetition of the Psalms—ancient Israelite prayers handed down by the Christian tradition in the context of particular, often Christological, interpretations—will likely sound rote and deadening. What of the immediacy of the monk’s relationship to God? What of his feelings in the face of the divine? What spontaneity can exist in the monk’s engagement with God within the context of such a regimented and uniform prayer life? If the monk is reciting another’s words rather than his own, how can the feelings engendered by these words be his own and so be sincere?

Yet, for Benedict, as for Cassian on whose work he liberally drew, the intensity and authenticity of one’s feeling for God is enabled through communal, ritualized prayer, as well as through private reading and devotion (itself carefully regulated).9 Proper performance of “God’s work” in the liturgy requires that the monk not simply recite the Psalms. Instead, the monk was called on to feel what the psalmist felt, to learn to fear, desire, and love God in and through the words of the Psalms themselves. For Cassian, we know God, love God, and experience God when our experience and that of the Psalmist come together:

For divine Scripture is clearer and its inmost organs, so to speak, are revealed to us when our experience not only perceives but even anticipates its thought, and the meaning of the words are disclosed to us not by exegesis but by proof. When we have the same disposition in our heart with which each psalm was sung or written down, then we shall become like its author, grasping the significance beforehand rather than afterward. That is, we first take in the power of what is said, rather than the knowledge of it, recalling what has taken place or what does take place in us in daily assaults whenever we reflect on them.10

When the monk can anticipate what words will follow in a Psalm, not because he has memorized them, but because his heart is so at one with the Psalmist that these words spontaneously come to his mind, then he knows and experiences God.11

The word translated here as “disposition” is derived from the Latin affectus, from the verb afficio, to do something to someone, to exert an influence on another body or another person, to bring another into a particular state of mind. Affectus carries a range of meanings, from a state of mind or disposition produced in one by the influence of another, to that affection or mood itself. In many instances, affectus simply means love. At the center of ancient and medieval usages is the notion that love is brought into being in one person by the actions of another. Hence, for Cassian, as later for Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153), our love for God is always engendered by God’s love for us. God acts (affico); humans are the recipients of God’s actions (so affectus, the noun, is derived from the passive participle of afficio). Hence the acquisition of proper spiritual dispositions through habit is itself the operation of the freely given grace that is God’s love. There is no distinction here between mediation (through the words of scripture) and immediacy (that of God’s presence), between habit and spontaneity, or between feeling and knowledge.

Of course, the affects, moods, or dispositions engendered by God are not only those of love and desire. Fear, dread, shame, and sorrow, gratitude, joy, triumph, and ecstasy are all expressed in the Psalms and in the other songs found within scripture. According to Cassian, the Psalms lay out the full realm of human emotion, and by coming to know God in and through these affects, the monk comes to know both himself and the divine:

or we find all of these dispositions expressed in the psalms, so that we may see whatever occurs as in a very clear mirror and recognize it more effectively. Having been instructed in this way, with our dispositions for our teachers, we shall grasp this as something seen rather than heard, and from the inner disposition of the heart we shall bring forth not what has been committed to memory but what is inborn in the very nature of things. Thus we shall penetrate its meaning not through the written text but with experience leading the way.

Here, experience is physical, mental, and emotional: the monk is said both to have passed beyond the body and to let forth in his spirit “unutterable groans and sighs,” to feel “an unspeakable ecstasy of heart,” and “an insatiable gladness of spirit.”12 The entire body and soul of the monk is affected; he is transformed by the words of the Psalms so that he lives them, and through this experience he comes to know, with heart and body and mind, that God is great and good.

The entire body and soul of the monk is affected; he is transformed by the words of the Psalms so that he lives them.

For Cassian, Christians attain the height of prayer and of the Christian life itself when

every love, every desire, every effort, every undertaking, every thought of ours, everything that we live, that we speak, that we breathe, will be God, and when that unity which the Father now has with the Son and which the Son has with the Father will be carried over into our understanding and our mind, so that, just as he loves us with a sincere and pure and indissoluble love, we too may be joined to him with a perpetual and inseparable love and so united with him that whatever we breathe, whatever we understand, whatever we speak, may be God.13

Although the fullness of fruition in God will never occur in this life, the monk daily trains himself, through obedience, chastity, poverty, and most importantly prayer, to attain it.

Cassian’s understanding of the role of the Psalms in the monastic life lays the foundation for monastic thought and practice throughout the Middle Ages. Many of the most elegant and emotionally nuanced accounts of experience and its centrality to the religious life can be found in the commentary tradition, in which monks (and occasionally nuns) meditatively reflect on the multiple meanings of scriptural texts.14 Among the masterworks of medieval commentary, Bernard of Clairvaux’s Sermons on the Song of Songs, opens with reference to the centrality of scriptural songs to monastic experience—not only the Psalms, but also the songs of Deborah (Judges 5:1), Judith (Judith 16:1), Samuel’s mother (1 Samuel 2:1), the authors of Lamentations and Job, and all of the other songs found throughout scripture. “If you consider your own experience,” Bernard writes, “surely it is in the victory by which your faith overcomes the world (1 John 5:4) and ‘in your leaving the lake of wretchedness and the filth of the marsh’ (Psalm 39:3) that you sing to the Lord himself a new song because he has done marvelous works (Psalm 97:1)?”15 Using the language of the Psalms and other biblical texts, writings with which Bernard’s mind and heart is entirely imbued, he describes the path of the soul as sung with and in the words of scripture.

The Song of Songs is the preeminent of songs, the one through which one attains to the highest knowledge of God. “This sort of song,” Bernard explains, “only the touch of the Holy Spirit teaches (1 John 2:27), and it is learned by experience alone.”16 He thereby calls on his listeners and readers to “read the book of experience” as they interpret the Song of Songs.

Today we read the book of experience. Let us turn to ourselves and let each of us search his own conscience about what is said. I want to investigate whether it has been given to any of you to say, “Let him kiss me with the kiss of his mouth” (Song of Songs 1:1).

Here Bernard suggests that it is through attention to “the book of experience” that the monk can determine what he has of God and what he lacks. Again, the goal is to see the gap between one’s experience of God’s love and one’s love for God and then to meditate on, chew over, and digest the words of the Song so that one might come more fully to inhabit them. The soul should strive, Bernard insists, to be able to sing with the Bride of the Song, “Let him kiss me with the kiss of his mouth.” “Few,” Bernard goes on to write, “can say this wholeheartedly.” His sermons are an attempt to bring about in himself and his readers precisely this desire. Only in this way can the soul ever hope to experience the kiss itself and hence to speak with the Bride in her experience of union with the Bridegroom.17

For Bernard, such experiences of union with the divine are only ever fleeting in this life. Moreover, he is interested in interior experience rather than in any outward expression of God’s presence. Claims to more extended experiences of the divine presence and of the marking of that presence on the mind and body of the believer—in visions, verbal outcries, trances, convulsions, and other extraordinary experiences—will shortly follow (and will be particularly important in texts by and about women). They will spread, moreover, outside of the monastery and convent, into the world of the new religious orders, the semireligious, and the laity. The questions asked in North America about what constitutes true religious experience and what is false or misleading, generated not by God but by the devil or by natural causes, has its origins in similar deliberations generated by such experiences as they came to prominence in the later Middle Ages.

Most important for our discussion is the way in which ritual engagement with ancient texts leads to, articulates, and enriches the spiritual experience of the practitioner. “Mere ritual,” within this context, would be ritual badly performed. True engagement in ritual and devotional practice, on the other hand, is the very condition for spiritual experience. There is a full recognition of the work involved in transforming one’s experience in this way.18 Yet, at the same time, medieval monastic writers insist that this transformation can occur only through grace. As I suggested above, there is no more contradiction here than there is in the claim that spiritual experience is both mediated and immediate, ritualized and spontaneous. If God acts through scripture, then in reading, reciting, and meditating on scripture one allows oneself to be acted on by God. Work and grace are here thoroughly entwined through love.

To many contemporary readers, however, there might still seem to be something profoundly different between medieval conceptions of spiritual experience and their own. Even among the growing number of Americans who understand certain kinds of practice—meditation, prayer, and devotional reading among them—as essential to their spiritual experience, there is a suspicion of the particular form such practices take within Christianity and other religious traditions. I suspect that what is at issue here is the association of experience itself, and spiritual experience in particular, with what, for lack of a better word, I will call individualism.

A series of common questions seem to underlie many people’s conception of spiritual experience. How am I to have my own experience of the divine? How can I experience the divine personally, and isn’t such a desire rendered impossible within the framework of institutions that direct my understanding and experience of God? What happens to that aspect of my experience that is irreducible to anyone else’s? On the one hand, many who consider themselves spiritual understand their spirituality in terms of an attunement with nature or spirit—something that is bigger than and lies beyond the boundaries of themselves. Yet, on the other hand, there is a keen desire for this experience to be one’s own. What the medieval monk or nun whose ritual performances I have described here strives to attain is an experience of God that is in conformity with that of the Psalmist and other scriptural authors. The experience must become one’s own, and Bernard insists on the continued specificity of the individual soul. Yet, at the same time, to be a true Christian is to share in a common experience of God.

Or perhaps the concern that many have with the rich spirituality of Christian monasticism may be understood in a slightly different way. Perhaps the concern is with the extent to which Christian monastic life—and the forms of devotional life that stem from it—demands a radical submission to something external to oneself. What happens, then, to individual freedom? What happens to the individual responsibility—religious, ethical, and political—that is concomitant with that freedom? Perhaps we can read the contemporary spiritual seeker less as one who makes seemingly solipsistic demands for an experience particular to herself than as one concerned with handing herself over to another—be it the abbot or abbess to whom one promises absolute obedience, the Psalmist whose words one understands as that of God, or divine love itself—that monastic practice demands.19

Isn’t the desire to constitute oneself as a spiritual person outside of larger communities illusory, in that we are always constituted in and through our interactions with others?

From this perspective, the debate between the “spiritual” and the “religious” (or between “true” and “false” religious experience) is less about their relative authenticity, sincerity, and spontaneity than about the conceptions of the person, God, and their relationship that underlie competing conceptions of spiritual or religious life. Must we hand ourselves completely over to God—and to the texts, institutions, and practices through which God putatively speaks—in order to experience God? Is this what established religious traditions or their “mainline” instantiations demand? How, if this is the case, are these injunctions best understood in relationship to claims to individual autonomy and responsibility? On the other hand, can we ever claim to be fully autonomous and free? Isn’t the desire to constitute oneself as a spiritual person outside of the framework of larger communities illusory, in that we are always constituted in and through our interactions with others and their texts, practices, and traditions? If, as many contemporary philosophers and theorists argue, we are always born into sets of practices, beliefs, and affective relationships that are essential to who we are and who we become, can we ever claim the kind of radical freedom that some contemporary spiritual seekers seem to demand? How might we reconceive our experience—spiritual or religious, whichever term one prefers—in ways that demand neither absolute submission nor resolute autonomy?

In a way, this is precisely what the medieval Christian monastic texts to which I attend here require. Submission must always be submission freely given. Without the will to submit, one’s practices are meaningless and empty. (And if one is forced, by external means, to submit, that too undermines the potential sacrality of one’s practices.) Yet, paradoxically, one’s freely given submission is engendered by God’s love, just as one receives God’s love—and the ever-deepening experience of that love—through engagement in human practices. Whether one accepts the theological claims of medieval Christian monastic writing, it opens up the vital interplay between practice and gift, submission and freedom, the experience of loving and being loved, that plays a continuing role in Western spirituality. Following Cassian, Benedict, and Bernard, I would suggest that it is only when we understand the way in which we are constituted as subjects through practice—all of us, spiritual, religious, and those who make claims to be neither—that we can begin to understand the real nature of our differences.

Notes:

- For a wonderful study of the development of conceptions of spirituality in the United States, see Leigh Schmidt, Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality (HarperOne, 2006).

- See Ann Taves, Fits, Trances, and Visions: Experiencing Religion and Explaining Experience From Wesley to James (Princeton University Press, 1999); and David Hall, “What Is the Place of ‘Experience’ in Religious History?” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 13 (2002): 241–250.

- See Wayne Proudfoot, Religious Experience (University of California Press, 1987); Robert Scharf, “Experience,” in Critical Terms for Religious Studies, ed. Mark C. Taylor (University of Chicago Press, 2000), 94–116; Amy Hollywood, “Gender, Agency, and the Divine in Medieval Historiography,” Journal of Religion 84 (2004): 514–528; and Hall, “Place of ‘Experience,'” 247.

- See, for example, Thinking Through Rituals: Philosophical Perspectives, ed. Kevin Schilbrack (Routledge, 2004); and Robert Wuthnow, After Heaven: Spirituality in America Since the 1950s (University of California Press, 1998).

- This despite the fact that historians and philosophers interested in the category of experience often suggest that there is nothing worthwhile said about it in the Middle Ages. See, most recently, Martin Jay, Songs of Experience: Modern American and European Variations on a Universal Theme (University of California Press, 2005).

- For this account of ritual, see Jonathan Z. Smith, “The Bare Facts of Ritual,” in his Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown (University of Chicago Press, 1988), 53–65.

- Benedict of Nursia, The Rule of St. Benedict 1980, ed. Timothy Frye, O.S.B. (The Liturgical Press, 1981), “Prologue,” 165.

- Ibid., chap. 7, pp. 201–203.

- The rule also calls on the monks to read, both in private and communally. Specially recommended are the Old and New Testaments, the writings of the Fathers, Cassian’s Conferences and his Institutes, and the Rule of Basil. According to Benedict, all of these works provide “tools for the cultivation of the virtues; but as for us, they make us blush for shame at being so slothful, so unobservant, so negligent. Are you hastening toward your heaving home?” Ibid., chap. 73, p. 297.

- John Cassian, Conferences, trans. Boniface Ramsey, O.P. (Newman Press, 1997), X, XI, p. 384.

- My account throughout is profoundly influenced by Jean Leclercq, O.S.B., The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture, trans. Catherine Misrahi (Fordham University Press, 1961). For a more recent analysis of monastic practice and the formation of the self, one deeply influenced by Leclercq as well, see Talal Asad, “On Discipline and Humility in Medieval Christian Monasticism,” in his Genealogies of Religions: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), 125–167.

- Cassian, Conferences, X, XI, p. 385.

- Ibid., X, VII, pp. 375–376.

- In part because of prohibitions against women publicly interpreting scripture, their reflections on experience often take other forms, among them accounts of visions, auditions, and ecstatic experiences of God’s presence or of union with God and—here paralleling Bernard’s practice—commentaries on these experiences.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons on the Song of Songs, in Selected Works, trans. G. R. Evans (Paulist Press, 1987), Sermon 1, V.9, p. 213.

- Ibid., Sermon 1, V.10–11, p. 214.

- Ibid., Sermon 3, I.1, p. 221.

- Here, I would take issue with the simplistic formulation of the relationship between belief and practice suggested by Louis Althusser. Althusser claims that Blaise Pascal said, “more or less: ‘Kneel down, move your lips in prayer, and you will believe.’ ” Althusser’s position is more complicated than these lines would suggest, but they have had an enormous purchase as indicators of an almost behavioralist account of the efficacy of religious (and other forms) of practice. Lost is the sense that mere repetition does little to transform the subject, but rather that one must look to one’s own experience, think, reflect, meditate, and feel the words of scripture, and work constantly to conform the former to the latter. See Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes Towards an Investigation,” in Lenin and Philosophy, and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster (Monthly Review Press, 2001), 114.

- This is precisely the issue faced by Sarah Farmer, the founder in 1884 of the Greenacre community in Eliot, Maine. Farmer brought an eclectic mix of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century spiritual movements together at Greenacre, among them Transcendentalism, New Thought, Ethical Culture, and Theosophy, as well as vibrant interest in non-Western religious traditions. Yet when Farmer became a member of the Baha’i faith—despite that movement’s call for “religious unity, racial reconciliation, gender equality, and global peace,” the more “free-ranging seekers” among her cohort objected strongly to what they saw as her submission to a single religious authority, its texts, beliefs, and practices. On Farmer, see Schmidt, Restless Souls, 181–225. The phrases cited here are on page 186.

Amy Hollywood is the Elizabeth H. Monrad Professor of Christian Studies at HDS.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Spirituality is a broad and subjective concept that encompasses a sense of connection to something greater than oneself. It often involves exploring questions about the meaning of life, the nature of existence, and the purpose of our existence.

Different cultures, belief systems, and philosophies have their own interpretations of spirituality. For some, it is linked to organized religion and faith in a higher power or deity. For others, it may be more secular, focusing on inner peace, mindfulness, and a sense of interconnectedness with the universe.

Hello, I have a similar line of thought. I am atheist but things fell into place about all this a few months ago I did not need to throw away the idea of the all-powerful after all. It is not God. It is greater than all Gods and religions. Some religions believe almost the same thing. The “all powerful all” is simply the totality of what is. It had no mind or beingness at first. It was what we call the big bang. Life evolved with no designer or God. This totality still is all and still has all power. Sentients is within it. We serve the all powerful and its servant. This is a very big very old universe. I speculate very advanced extremely advanced beings are here and can be connected to with prayer and mediation. Of course they agree with spiritual atheism. They also know about the all powerful all. It is where they came from just like us.