Perspective

Searching for Balance

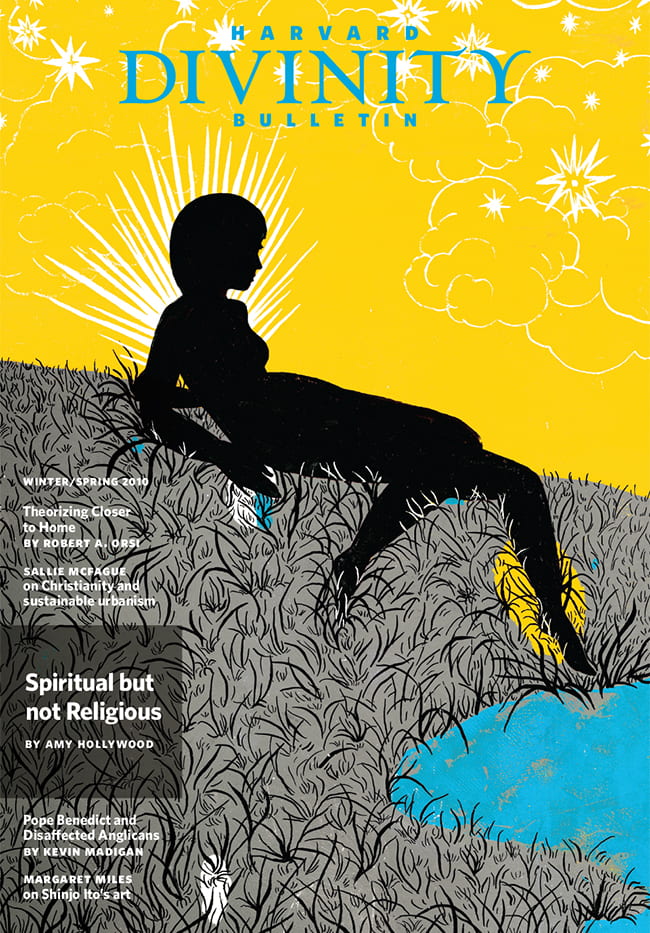

Illustration by Rachel Salomon. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Kathryn Dodgson

In his recent collection of essays, The Education of a British-Protected Child, the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe writes that he is fascinated by the middle ground: it “is neither the origin of things nor the last things; it is aware of a future to head into and a past to fall back on; it is the home of doubt and indecision, of suspension of disbelief, of make-believe, of playfulness, of the unpredictable, of irony.”

The idea of a middle ground or a middle way, both in terms of living in moderation and in accommodation and in terms of an ongoing mutual human quest for a common meeting place, strikes a chord with me—not least because we are so assaulted by extremes: the extremes of deeply entrenched beliefs and unremitting religious (or ethnic) strife; the mind-boggling daily expense of ongoing wars over commodities fought in the name of justice or democracy, juxtaposed with the tragic costs of worldwide poverty and the injustice of human degradation; the excessive swings of financial markets; the frighteningly rapid rate and extent of ecological and environmental damage wreaked by practices that, in the best light, can be laid at the feet of human ignorance or shortsightedness, and at worst are the results of an excess of blatant human greed.

For Achebe’s people, the Igbo, the middle ground is considered lucky, desirable. In his words, the Igbo prefer “not singularity but duality. Wherever Something Stands, Something Else Will Stand Beside It.” On one level, it is an easily accepted adage that none of us lives in isolation, either from each other or from our surroundings. What I do or say does have an impact, on someone or something, somewhere. If I am to have a valid and true presence, I have to allow, equally and with respect, the presence of another. But to find our way forward to a future that embraces more balance or harmony requires resolve, continual reassessment, and an imaginative way of seeing. It takes courage to step outside of our narrower perspectives and the worlds we are comfortable inhabiting to question our paradigms and to see that our perceptions, and the convictions and truths we so strongly adhere to, are defined by the social and cultural contexts which we have inherited—and so may not be the same “true reality” for others.

Readers of the Bulletin will recognize that discussions around issues of quest, or searching—for paths toward the divine; for a course away from acrimonious assessment or adversarial impasse and toward an acceptance of differences; for ways to balance belief and teaching, or faith and practice, or faith and reason—have commonly appeared in its pages, as our authors engage us in shared human dilemmas.

In this issue, in her review of the exhibit of the Buddhist monk and sculptor Shinjo Ito, Margaret Miles reflects on the concepts of balance and harmony that bring to mind new considerations of unity and diversity, which might in turn allow for more intercultural, interreligious understanding. Emran Qureshi’s coverage of medieval Muslim travelers and travel writers echoes the personal experiences Stephanie Saldaña describes about living in a neighborhood in Damascus, where histories and peoples and beliefs intermingle, and a community of émigrés and exiles form close human bonds while still retaining their own identities and self-integrity.

In her search for prayer spaces in international airports, Shahnaz Habib comes to realize that what you think you are looking for becomes something quite different when you set aside your initial assumptions and truly see, translating the Igbo duality into “There’s no inside without an outside.”

Sallie McFague reminds us that how we see ourselves must include nature, our place within it, and our responsibility for it and for others with whom we need to share severely limited resources. The excesses of the sort of lifestyle that those of us who live in North America, especially, have come to accept as our given right must give way to an ethic of “self-emptying,” or self-limitation.

The Dialogue authors examine different sorts of adjustments leading to new definitions of community: from an unexpected accommodation between the Roman Catholic Church and concerned Anglican priests, to the new course forged by young Muslims as they bridge inherited and adopted cultures; and from a re-evaluation of “alone-ness” and the mutual interdependence of solitude and community, to musings on how the newer tools of social media (and those who use them) are challenging churches to engage in new forms of conversation.

In the lead feature, Amy Hollywood examines the perhaps flawed distinction between what is understood as being spiritual and what is religious, whereby authentic and unique personal “experience” of the divine occurs separately from, or outside of, a tradition or a communal authority. Yet this raises the question of whether we are truly autonomous or whether, in fact, “we are always born into sets of practices, beliefs, and affective relationships that are essential to who we are and who we become.”

Robert Orsi cautions that theorists of religion (and all of us) cannot truly “engage the other as subject” without being subjects ourselves, without “the recognition of our common subjection to history, contingency, and fate”—our personal inheritances. We need to understand those from whom we are descended, and the imperatives that drove them, in order to understand ourselves and our perceptions.

And, we cannot understand or accept our own inheritance if, in our theorizing, we leave people out. What about those who are absent from our histories, the displaced, the devalued, the “disposable” (Orsi’s word)? To return again to Achebe, he quotes the Bantu saying, “A human is human because of other humans.” Thus, the fate of our own humanity rests on how we measure the humanity of others.

Kathryn Dodgson is director of communications at Harvard Divinity School.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.