Featured

Remaking a ‘Learned Ministry’ for Each New Era

2015 Seasons of Light service in Andover Chapel. Photo by Brian Tortora

By Stephanie Paulsell and Dudley C. Rose

In one of the earliest statements of the mission of Harvard College, the Puritan founders famously wrote that, once they had built their churches and established their government, “one of the next things we longed for and looked after was to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity; dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches, when our present ministers shall lie in the dust.”

From that longing, Harvard College was born, and—one hundred and eighty years later—Harvard Divinity School. As the Divinity School’s mission has broadened over the last two hundred years to support a wide range of vocations from minister to scholar to chaplain to teacher to activist to artist and beyond, the School’s mission to educate students for learned ministry has been remembered and reinterpreted, cherished and critiqued in Harvard Divinity School’s master of divinity program.

The history of, and vocation to, learned ministry now belongs to a more diverse group of students than the Puritans could have imagined. Students from Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, Jewish, Hindu, and Unitarian Universalist traditions, along with religious “nones” and students who belong to more than one religious community, are now the heirs of the Harvard founders’ commitment to learned ministry. What learned ministry means in this context is by no means settled or singular, nor are the forms it might take decided upon. As has been true in every generation, our students give these ideas shape and heft through the living of their lives in ministry.

The journey from the education, in Harvard College, of literate clergy for the New England churches to the education of ministers and religious leaders for a much broader range of religious, multireligious, and nonreligious communities has unfolded not only against the backdrop of a changing American religious landscape, but also within a system of theological education undergoing radical transformation. Harvard’s establishment of a Divinity School in 1816 bears testimony to two movements in the landscape of education for Protestant Christian clergy: the secularization of university education and the explosion of theological schools, most of them denominational seminaries. In the opening decade of the nineteenth century, Harvard’s internal controversy between orthodox Calvinist Congregationalists and Unitarians led the former to found Andover Seminary in 1807. Presbyterians founded Princeton Theological Seminary in 1809, and the race was on. By 1840, nearly every American Protestant denomination had at least one seminary of its own. By 1918, more than one hundred individuals representing approximately fifteen Protestant denominations and fifty of their graduate schools gathered for a conference at Harvard to discuss the state and standards of graduate theological education for Protestant Christian ministry. The meeting would ultimately lead to the establishment of the Association of Theological Schools (ATS).

Peter Gomes, STB ‘68, preaches in 2008. Gomes was the Plummer Professor of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church for forty years and was a much beloved preaching and homiletics professor at Harvard Divinity School. He mentored hundreds of HDS students—not only those who planned to enter parish ministry or chaplaincy, but also many who went on to careers in other fields. HDS Photograph / Steve Gilbert

The formation of the ATS also signaled an era of emerging ecumenism within the society and in theological education. The bitter divides of the early nineteenth century were largely replaced by an emerging liberal-progressive Protestant Christian consensus. In 1922, Harvard Divinity School and Andover Seminary rejoined but, in 1926, were torn asunder, not by internal controversy but by a ruling of the Supreme Judicial Court. Presaging the later formation of the Boston Theological Institute, at various moments in this era, faculty members of Andover Theological Seminary (Baptist), Episcopal Theological School (Episcopal), Newton Theological Institution (Congregational), and Boston University School of Theology (Methodist) enjoyed faculty status at Harvard (nondenominational), and students had cross-registration privileges across all the schools.

The next three decades saw many of these trends grow. The first women were enrolled as students at HDS in 1955, though the first woman to receive tenure on the faculty would have to wait thirty more years, until Margaret Miles in 1985. The year 1958 saw the first occupant of the Charles Chauncy Stillman Chair in Roman Catholic Theological Studies—Christopher Dawson—and the formation of the Center for the Study of World Religions (CSWR).

The formation of the CSWR led to dramatic changes in the School. While the meaning of the word “minister” had come to encompass far more than ordained vocations, and, even as attention to other religious traditions had increased, the School’s theological center had remained Protestant Christian. The 1980 curriculum was mapped onto three concentric categories: at the center, Scripture (meaning Old and New Testament); one circle out, Christianity and Culture; and outermost, World Religions. With the introduction of the MTS degree in the early 1970s—but also within the MDiv—increasing numbers of HDS students found the Christian curricular center hard to reconcile with their academic and vocational aspirations, let alone their religious identities. Many students recognized HDS to be a place of religious diversity. They understood each of their own traditions to be a hub, with its own sacred texts, histories, theologies, and practices spreading forth as spokes.

In 2003, Janet Gyatso, the Hershey Professor in Buddhist Studies, gave her Convocation Address, “Where Do We Stand?” Her talk inspired new conversations among faculty, staff, and students about how the MDiv program might educate students from many religious backgrounds, and it provided inspiration for the most extensive curricular revision in HDS’s history. Paying homage to the Divinity School’s Protestant Christian inheritance, Gyatso noted in her address that “A budding Zen priest would learn enormously from Peter Gomes on how to preach with wit and passion.” She offered a number of other examples to emphasize her conviction that, even as the MDiv program at HDS became self-consciously multireligious, it would bear deep marks of its genealogy. Gyatso reasoned that as a religious tradition such as Zen Buddhism grew in America, its institutional expressions and the expectations of its adherents might begin to resemble existing American religious forms. “I want us never to forget,” she insisted, “that this American religion . . . is just in the making.”

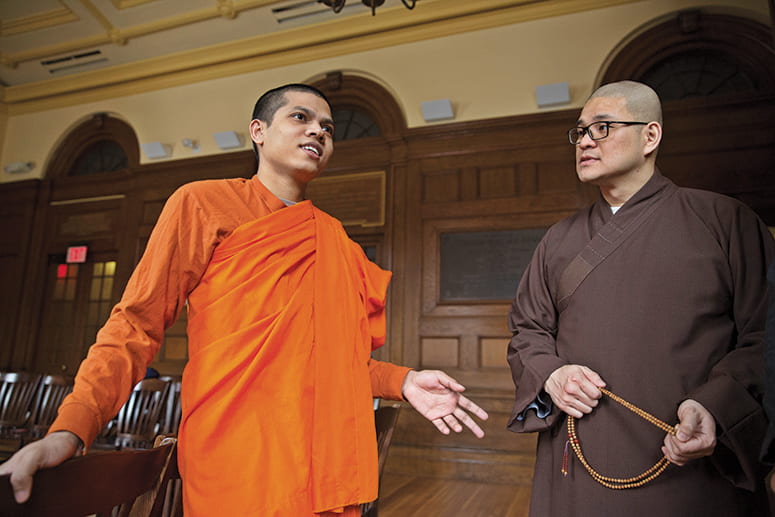

Priya Rakkhit Sraman (left), a Buddhist monk from Bangladesh, speaks with Seng Yen Yeap (holding beads), a monk from Hong Kong. These and other Buddhist practitioners have come to HDS to study as part of the Buddhist Ministry Initiative. Harvard News Office photograph

As our colleague Diana Eck has often reminded us, religions do not travel through history in pneumatic tubes, unaffected and unchanged by their encounters with other traditions. Religious traditions and the cultures in which they take root are anything but static. They reshape one another, constantly. And while it is certainly true to say that Harvard Divinity School still manifests its Protestant Christian roots—even the Convocation at which Janet Gyatso spoke retained the shape of a Protestant Christian worship service—it is equally as true to say that the School and what it teaches is “just in the making.”

When HDS committed itself to a multireligious master of divinity program, we wanted to acknowledge the changes and mutual influences that were already afoot. The United States was already a pluralistic society, and many families, neighborhoods, and communities were already multireligious, as was the Divinity School itself. Indeed, long before the new curriculum was implemented, there were small numbers of Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu students, as well as students who adhered to no religious tradition, pursuing the MDiv degree alongside Christian and Unitarian Universalist students. Most sought to prepare themselves for chaplaincy in multireligious contexts such as hospitals, prisons, and schools. But because the MDiv curriculum was structured under the “Christianity and Culture” rubric, these students had to submit petitions to replace Christian scripture requirements with the study of the holy books of their own traditions.

When the faculty revised the master of divinity curriculum, our aim was to strengthen ministry education for all students in the program, no matter their religious background. We wanted to offer more shared intellectual experiences that all students could draw upon—an introductory course in ministry studies, for example, and a course in theories and methods in the study of religion—while at the same time strengthening each student’s critical engagement with the scriptures, theologies, histories, and practices of their own religious traditions. We wanted to free MDiv students from the cumbersome work of petitioning to count the courses they needed to engage critically with their own traditions. We wanted to encourage them to seek the courses they needed from across the University, whether that be a language course, a course in the Qur’an, or one in the literature of the transcendentalist movement. And, we wanted the fruitful, creative thinking across traditions for which Gyatso had called, and out of which innovative ministries were already taking shape, to continue.

Ministry education at HDS has been transformed more quickly than we expected, as gifted students from a range of religious backgrounds have sought and gained admission to the master of divinity program and as our faculty and curricular offerings have become more diverse. In her 2003 Convocation Address, Gyatso had also expressed her hope that the study of Buddhism at HDS would become “brilliant in a thousand ways on how Buddhist intellectual and literary history can contribute to real-life pastoral contexts.” MDiv students at HDS today can take courses in Buddhist practices of compassionate care for the dying, spiritual care and counseling in Muslim communities, the practice of peacemaking across religions, and poetry as a resource for facing death and grief (as well as taking the courses in Christian preaching and the Jewish liturgical year that existed before the curriculum change).

There is a lot of work still left to be done in developing courses in the pastoral practices of the religious and spiritual traditions represented in our student body. But theological education for ministry at HDS is now being deeply and profoundly shaped by a range of traditions, practices, and perspectives. For example, all MDiv students, no matter their religious background, now leave HDS with an understanding of pastoral care that has been shaped by Buddhist thought and practice. The Buddhist influence on the theory and practice of pastoral care has already become a distinctive feature of education for ministry at HDS.1

As the School began significantly reforming its inherited Protestant Christian architecture—even moving some of the weight-bearing walls of the edifice—Charles Hallisey, Yehan Numata Senior Lecturer on Buddhist Literatures, captured the spirit of these changes when he said that the MDiv curriculum was moving from a stance of learning about other religious traditions to a stance of learning from other religious traditions. Decentering Christianity did not, of course, erase the Protestant Christian ethos of HDS, but it significantly changed the discourse. The commitment to learn from more than one religious tradition substantively enriches the learning that goes on in the School. It also democratizes truth claims.

Some worry that a ministerial formation that learns from other traditions results in a vague and shapeless minister. Former HDS Dean Krister Stendhal was fond of saying that interreligious engagement should result in a stew, not an over-processed soup. The ingredients should inform one another, and to some degree change one another, yet remain distinguishable. Our experience at HDS suggests that our students regularly become more aware, knowledgeable, and committed to their traditions as they prepare in our program. Students and alumni report that they have had to more clearly articulate the beliefs and practices of their own traditions at HDS, because they did not have the luxury of an assumed common religious language. As they engage in this more careful articulation, many have realized that they need to learn more about their own tradition; they knew less of it than they thought they knew. The potato in the stew actually becomes a better potato!

Elizabeth Eaton, MDiv ’80, was installed as presiding bishop in 2013 and was the first woman to lead the four million–member Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Asked about the meaning of her installation, Eaton replied that God’s gifts could be poured out on anyone, even “on someone who happens to be female from Ohio.” Photo courtesy Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

The landscape of theological education continues to change, as we are losing many of the freestanding denominational seminaries that were founded in the early nineteenth century. Protestant seminaries often do not have the resources to broaden their educational models, even if they have wanted to. Their financial capacities are already stressed to the point of breaking.2 As more and more seminaries change to low-residency online programs, merge, or disappear, it becomes increasingly important that universities maintain their commitment to their divinity schools. If full-time, three-year programs of ministerial formation are going to survive in this country, they are going to survive, in large part, in the universities.

This will inevitably change theological education—and potentially for the better. Universities possess the infrastructure and resources to support the crucial work of preparing new generations of ministers for contexts both familiar and new. The intellectual breadth available within universities allows “learned ministry” to be influenced by every form of human knowledge and to educate students in a wide range of traditions. Today’s learned ministers must be formed in their religious traditions within a multireligious environment and curriculum. But they must also understand how to navigate political and social realities, properly manage organizations, negotiate conflicts, work for justice and peace, and provide spiritual care. The whole university is necessary for the task of educating learned ministers. Certainly, without the wider resources of Harvard University, the Divinity School could not welcome such a diverse range of students into its MDiv program, or offer our students such a rich curriculum.

The benefits of the relationship between universities and ministerial education do not just flow in one direction. Universities often seem to think of their divinity schools as a repository of values by which the university hopes to be influenced. But the ministers who receive their education within a university divinity school bring more than values to the university’s table. They bring a desire to cultivate not only new knowledge but new ways of living from their encounter with the histories, theologies, literatures, practices, and languages that they study. They connect the university to a wide array of local communities through their work in field education, and they cultivate spaces within which to reflect on the intersection of the university and the world around it.3 Furthermore, in our increasingly religiously plural society, many fields within the broader university are coming to understand the need within their areas and professions for religiously literate scholars and practitioners. Because nothing human is alien to the minister, there is nothing that can be learned in a university that cannot be put to good use in ministry—and that fact is transformative, for the minister and for the university. MDiv students help make “One Harvard” a reality.

In 2016, for the first time the number of Jewish students in ministry studies merited an offering in Jewish polity. Rabbi Sally Finestone, ThM ’99, denominational counselor to Jewish students, taught the course. The HDS Office of Ministry Studies employs part-time denominational counselors who serve the needs of particular faith communities at the Divinity School. HDS Photograph / Michael Naughton

When we say “learned ministry,” we hope our students hear the echo of the aspirations of the School’s Protestant Christian founders, but we also hope they hear a call to a life of ministry that is marked by the learning that happens in classrooms and libraries, in hospitals and prisons, in religious communities and in social movements, and by bringing what is learned in one context to bear on another. We hope they hear a call to a life of rigorous and loving attention, a life turned toward the world’s challenges and sorrows, bearing the best resources it knows how to gather. We hope they hear a call to ministry in which nothing that can be learned is off-limits or irrelevant to their work as ministers—a call to the creative refashioning of what they have learned in the classroom and the field, in prayer and study, into ministries within which people and communities can flourish.

We who teach here understand that HDS’s Protestant Christian heritage permeates the place even as the School claims a robust pluralism. We also understand that the ground keeps shifting. The religious landscape of the United States and the world is not and never has been static. We strive to educate ministers to become spiritually, intellectually, and pastorally agile so they may minister well in a changing present and an unknown future. Finally, HDS intends to train ministers who learn from traditions other than their own, not only because doing so will enrich their own traditions, but also because knowledge of and mutual respect among religious traditions is necessary if there is ever to be a just and peaceful world.

As multireligious ministry education continues to develop at HDS, our challenge is to take the fullest possible advantage of the opportunities our diverse community offers for learning from each other and from the traditions we live and study. When they encounter challenges, we see our students digging even more deeply into the resources of religious thought and practice, literature, social movements, and more. We see them seeking new ways to cherish and protect the dignity of every person, and new language that cultivates solidarity across difference and speaks truthfully about the things that matter most. We are fortunate to be teaching and learning with our students, and welook forward with hope to the difference our students will make, and that they are already making, in the world.

Notes:

- The Buddhist Ministry Initiative trains future Buddhist religious professionals and coordinates a range of courses on the history, thought, and practice of Buddhism, in Buddhist languages, and in Buddhist arts of ministry. It also supports the field education of Buddhist ministry students in hospitals and other sites of pastoral care, and offers the insights of Buddhist textual traditions and practices to students from all religious traditions who study ministry at HDS. The initiative was launched in 2011 thanks to a $2.7 million gift from The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation.

- The Boston Theological Institute (BTI), a consortium of ten theological schools, divinity schools, seminaries, and a rabbinical school in the Boston area, is a case in point. Three of the ten schools in the BTI are freestanding schools of Protestant Christian orientation (American Baptist, Episcopal, United Church of Christ). Of those three, the two schools affiliated with the so-called mainline denominations have announced closings in the last two years.

- Approximately one hundred accredited field education sites are affiliated with HDS and are open to MDiv and MTS students. These sites include parishes, educational institutions, community-based social justice agencies, hospitals, and other health care institutions. An average of 100 students participate in field education each year (including summer placements).

Stephanie Paulsell is Susan Shallcross Swartz Professor of the Practice of Christian Studies. Dudley C. Rose is associate dean for ministry studies and Lecturer on Ministry.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.