In Review

Reading St. Therese

By Stephanie Paulsell

In the late summer of 1970, the year I was to enter the second grade, my hometown closed the schools. The last week of August came and went, and we children all remained at home.

During the 16 years since Brown v. Board of Education, my hometown of Wilson, North Carolina, had moved with slow reluctance toward integration. It was 12 years after the United States Supreme Court ruled the concept of “separate but equal” unconstitutional before Wilson took its first steps toward integrating its schools, and, even then, Wilson, like many other towns and counties in the south, did only the minimum: it offered school choice, but it did not actively assign children to different schools. Finally, the courts insisted: the Wilson Public Schools must integrate. My hometown responded by shutting the doors of all its schools and locking them tight.

When the town refused to give our parents any indication of when the schools would reopen, my parents sent me to a Roman Catholic school named for St. Thérèse of Lisieux, a saint who lived in France in the late nineteenth century, a Carmelite nun who entered a monastery at the age of 15, died of tuberculosis at age 24, and became famous for the “little way” to God that she wrote about in her autobiography.

St. Therese Catholic School was already integrated. Many of my African American classmates arrived each morning in a yellow school bus that said “Saint Alphonsus” on its side. The school was run by the Sisters of Providence: Sister Mary Griffin was our principal and Sister Mary Ann was the second-grade teacher. They lived in a convent, a big white house, next to the school.

Story of a Soul

Sister Mary Griffin and Sister Mary Ann became friends of our family. They played their guitars and sang in our living room on the evenings when my dad’s students came to dinner; they joined in on the long discussions of prayer and theology and the Vietnam War going on at our dining room table or in our backyard; they let my dad’s students do their laundry at the convent. I wanted to be just like them, and one evening, while everybody was sitting around talking, I crawled up into Sister Mary Griffin’s lap and poured out my desire to become a Roman Catholic. Later, when we were all standing around in the front yard, my dad picked me up by one arm and one leg and swung me in circles. “You want to be a what?” he laughed while I giggled uncontrollably. That’s how so many of those evenings ended, with all of us laughing in the yard as the dusk deepened into darkness.

At school, Sister Mary Griffin and Sister Mary Ann taught us and disciplined us and played with us. Every day at recess, someone would plug a 45 rpm record player into the outdoor socket. I remember Sister Mary Griffin coming outside to dance with us to the music of the Jackson 5, swinging her head with its tight cap of hair to the beat.

The other thing we did at recess was to climb around on the shrine of St. Therese until Sister Mary Griffin and Sister Mary Ann made us stop. The shrine was made of stone and held within it a statue of “the little flower,” as St. Therese was often called. But there was also room for a small child or two in the niche that held her. It was hard to resist climbing into that shrine. The sisters had to shoo us out of it every day.

The public schools opened about three months late that year, and busing finally began. At the end of the year, the Sisters of Providence—including my beloved Sister Mary Griffin and Sister Mary Ann—were sent away from our diocese. When I entered the third grade, yellow school buses appeared all over Wilson, and I attended a formerly segregated school for black children on the southeastern edge of town.

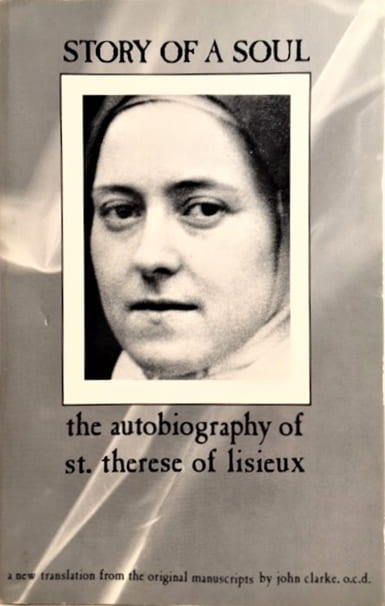

My days at St. Therese were over, but St. Therese entered my life again a few years later, in 1975. My dad had a copy of a brand-new translation of the original manuscripts of her autobiography, Story of a Soul, and he loaned it to me. It was a big gray book with a sketch of the saint on the cover. The print looked almost like typescript, as if the translator had been so eager to make it available to English readers that he couldn’t wait for a fancier printing press to do the job. Inside were photos of St. Therese herself. She had a face like an apple, round and full, and eyes that seemed to look out of the page and straight into me.

In her autobiography, Therese tells a story about being loaned a book about the spiritual life by her father when she was 14 years old. “This reading,” she writes, “was one of the greatest graces in my life. I read it by the window . . . and the impressions I received are too deep to express in human words” (102).

St. Therese’s book carved out a place of solitude inside me, a place I could go to meet her; a place to meet God.

That’s what reading St. Therese’s book was like for me. Her book carved out a little place of solitude inside me, a place I could go to meet her, a place I could go to meet God. Reading her book, I could feel God shining on me, like a light from a distant star.

What did I love about her? I loved her account of playing “hermits” with her sister Marie. One would pray while the other worked in the garden; then they would switch, all in total silence. I loved the way she would build little altars in niches in the walls of her house. I loved the way she imagined herself as a little ball the child Jesus picked up and played with from time to time. I loved that she had thrown herself at the feet of Pope Leo XIII during a papal audience in which she had been told not to speak to beg him to allow her to become a nun, and I loved that she tried to turn the smallest interactions with family and friends into opportunities to cultivate love and holiness. I loved that she used italics and capital letters and exclamation points so liberally that her words seemed to leap off the pages. I loved her accounts of the feast days she observed with her family, the processions she participated in with her church. I loved that she prayed for the criminals she read about in the paper, hoping that they would turn toward God and seek forgiveness for their sins. I began to comb through the Wilson Daily Times looking for criminals of my own to pray for.

St. Therese’s “little way” did not seem, to me, little at all. It seemed huge, spacious, full of places to explore—large enough, certainly, for me.

Elementary school gave way to high school and high school to college, and I found new books to read, new writers to admire. When I was a junior in high school, members of the Ku Klux Klan and a local neo-Nazi group in Greensboro, North Carolina, murdered five members of the Communist Workers Party. They shot them down in the street, in front of rolling TV cameras, and were found not guilty by a jury of their peers. When I arrived in Greensboro for college two years later, I was befriended by the widow of one of those murdered CWP members, and my political education began in earnest. The books I read from my dad’s shelf in those years were Dorothy Day’s The Long Loneliness and Thomas Merton’s Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander; from my mom’s, the writings of Virginia Woolf. If I’d thought about it, I’d probably have thought that St. Therese’s “little way” wasn’t up to the challenges of our day. (I was ignorant of the fact that Dorothy Day herself loved St. Therese and had even written a biography of her.) What our world needed was a big way out of the mess we had made: a change of consciousness, a conversion on a massive scale. Revolution. What did St. Therese’s pious musings have to say to the world I lived in? I had a warm memory of St. Therese, but I didn’t read her, or seek her out, during those years. It wasn’t until graduate school that I encountered St. Therese again.

In a seminar on Christian women mystics, I found her on the syllabus. So much of what I was learning in graduate school was deeply unfamiliar, and I was glad to see the name of a writer I remembered knowing and loving. I mentioned to a friend, a former Roman Catholic nun, that I was excited to get to read St. Therese again. “Ugh,” she said. “The little flower. She was crammed down my throat in the convent. We were all supposed to be like her, and who would want to be? I’ll be glad if I never read her again.”

This shocked me, the idea of St. Therese as a tool of oppression. But my memory of loving St. Therese as a child was still strong, and I turned to Story of a Soul with excitement.

I didn’t have my Dad’s old copy, the one I’d read as a child, so I bought a new copy in the bookstore, one without the photos of Therese. And I found that no one—not my teacher nor my fellow students—called her “Therese.” They called her Tay-rez, using the French pronunciation of her name: Thérèse Martin, Thérèse de Lisieux. As impossible as it was for me to imagine the school I attended in Wilson, North Carolina, as “Sainte Thérèse” Catholic School, I tried to get used to the sound of this new name, the feel of it in my mouth. And so, with an unfamiliar edition of her book, addressing her with a new name, I set out to reacquaint myself with the saint I had loved as a child.

In an essay on reading, the cultural critic Sven Birkerts remembers loving Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road as a young man. But when he returned to it years later, he found that “whatever magic had been there now survived as only a memory of magic.”1 That pretty much sums up my experience of reading Therese’s book as a 24-year-old. The italics and capital letters and exclamation points that had made her text come to life for me as a child seemed rather immature now, reminding me of the loopy handwriting of little girls who dot their “i’s” with hearts. She seemed overly obsessed with tiny domestic dramas in her home and in the convent to which she attached cosmic importance—for example, her description of her great “conversion” on a Christmas evening when she was 13 years old. The family had just returned from midnight mass, and her father, cranky and tired, expressed annoyance with Therese for her continued child-like love of opening presents after the service. Looking at her slippers filled with presents in front of the fireplace, he grumbled, “Well, fortunately, this will be the last year!” (98).

Ordinarily such a rebuke would have sent Therese into spasms of crying: “I was really unbearable because of my extreme touchiness,” she writes (97). But that Christmas night, she says, Jesus changed her heart: “Forcing back my tears I descended the stairs rapidly; controlling the poundings of my heart, I took my slippers and placed them in front of Papa, and withdrew all the objects joyfully. . . . Having regained his own cheerfulness, Papa was laughing. . . . I felt charity enter into my soul, and the need to forget myself and to please others; since then I’ve been happy!” (99).

Well, what kind of conversion is this, especially when compared with Paul being knocked from his horse on the road to Damascus, or Augustine hearing the voice of God in scripture and leaving his wild ways behind? She’s really just describing the kind of self-mastery that we all have to learn in order to grow up. Ordinary. Unremarkable.

And weren’t those fervent prayers for the murderers she read about in the paper sentimental at best and macabre at worst? And didn’t it seem like she wanted to enter the Carmelite monastery at age 15 so that she could be with the big sisters who had raised her after her mother died and who had entered the convent before her? And what about that passage where she talks about being splashed by dirty water in the laundry room by a nun who wasn’t taking care with her task? Is her choice not to wipe her face so as not to make the other nun feel bad really a way to holiness? “My dear Mother,” she writes to her prioress about this episode, “you can see that I am a very little soul and that I can offer God only very little things” (250). I’ll say. With all that God has to think about in the great, suffering world, did she really think God noticed how she responded to being splashed in the laundry room?

When I read St. Therese as a child, her words had opened space around me, above me, below me. I grieved that I couldn’t return to that space, “that great cathedral space which was childhood,” as Virginia Woolf once put it. St. Therese had set my feet in a broad place when I was 12, but when I was 24, she herself seemed to me utterly hemmed in—trapped by her piety, by her times, by her culture, by her gender. Like a lot of my classmates, I was searching among the women mystics of Christian history for models, for mentors. I found it much more comfortable—not to mention more intellectually and politically respectable—to read the saint for whom St. Therese had been named: St. Teresa of Avila, the great Spanish mystic of the sixteenth century. Now there was a saint: a reformer of her religious order, a founder of monasteries, a teacher, a mystic, an interpreter of scripture who clashed with the Inquisition. During her childhood, St. Teresa of Avila ran away from home with her brother to seek martyrdom, rather than looking for ways to make the littleness of her life holy. She wanted a big life, an “epic life,” as the novelist George Eliot later put it when she invoked St. Teresa in the prologue to Middlemarch. Teresa of Avila’s namesake, St. Therese, seemed but a pale imitation—St. Therese, the little flower, the child.

It is a tribute to the power of childhood memories that, 20 years later, I’ve found myself wanting to return to St. Therese, to read her again. I couldn’t bear, though, to read the copy of the book I’d read for my seminar 20 years ago. I felt that I needed to read the same book I’d read as a child, that very one. I needed the relic, the thing itself. Visiting my parents a few summers ago, I looked all over my dad’s study for that book, with no luck. But then, a few months later, I found an edition almost exactly like the one I’d read as a child in the bookstore of the Trappist monastery in Spencer, Massachusetts. The typeface was nicer, but the chapters were laid out on the page exactly as I remembered, and all the photos were there. It’s hard to describe what it felt like to find that book. “This is it!” I exclaimed to my husband and my daughter. They smiled patiently, and, I’m pretty sure, rolled their eyes behind my back. “Are you obsessed with her, Mom?” my 9-year-old daughter asked me.

I began reading the book slowly but soon picked up steam, because I couldn’t put it down. And I heard things in her writings that I hadn’t, somehow, heard before.

I heard her desire to be a priest, for one thing. How had my young feminist self missed this? Her frustration that she cannot be a priest juts to the surface throughout her writings and even through others’ remembrances of her. How I wish I were a priest, she would say, so that I could preach a good sermon on the Virgin Mary! She felt that one rarely heard a good sermon on the Virgin Mary: preachers tended to make her perfect, unable to be imitated, remote. Therese was drawn to stories of Mary’s humanity, like the one in the second chapter of the Gospel of Luke, where Mary doesn’t understand what Jesus means when he says to her, after she had lost him after the Passover festival in Jerusalem, “Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house?” It’s not perfection that attracts Therese to the mother of Jesus; it’s Mary’s ability to remain faithful and loving even in the face of events she doesn’t understand.

In a letter to her sister Marie she wrote, “I feel in me the vocation of the PRIEST. With what love, O Jesus, I would carry You in my hands when, at my voice, You would come down from heaven. And with what love would I give you to souls! But alas! While I desire to be a Priest, I admire and envy the humility of St. Francis of Assisi and I feel the vocation of imitating him in refusing the sublime dignity of the Priesthood” (192).

I love that; she’ll refuse the priesthood, not be denied it.

Not only did she want to be a priest, she also longed to be a missionary. She had hoped that God would let her live so that she could go to the Carmelite house in Hanoi. Unable to fulfill that goal, she corresponded with a young missionary priest and supported him with her prayers. In a letter to him, she assures him that her death will not separate them. When I die, she wrote, “there will no longer be any cloister and grilles, and my soul will be able to fly with you into distant missions. Our roles will remain the same: yours, apostolic [labor], mine, prayer and love.”2

I was also surprised to find, reading St. Therese this time around, that she spent the last year and a half of her life in what St. John of the Cross once called “the dark night of the soul.” On the night before Good Friday in 1896, Therese had a coughing fit in the night, and when she awoke the next morning, she was covered in blood and knew that her dying had begun. She was at first filled with joy at the thought of leaving this earthly exile and joining Jesus in heaven. But by Easter Sunday, that joy was gone, and it never came back, ever.

Even in this night of nothingness, with her vision of God’s love obscured, she stayed turned toward God, and she kept loving.

St. Therese died in 1897, quite young, at 24. If she had lived as long as some of her sisters lived, my lifetime might have overlapped—a little—with hers. She lived in an in-between time—in between a culture suffused with Catholic Christianity and its practices and a culture which would question the very existence of God. It was a time of great scientific and technological advances, the time when Marx, Freud, Darwin, and Nietzsche were doing their groundbreaking work. Although she was cloistered in a monastery, she was not immune to the great questions of her age. When faced with her imminent death, she fell into a trough of doubt and fear. She said it was like living in a country upon which an impenetrable fog had settled; try as she might, she could no longer make out the joyful confidence she had had in God’s love and care and promises. It was a night, as she put it, of nothingness.

But even in this night of nothingness, even with her vision of God’s love obscured, she stayed turned toward God, and she kept loving. Even though I no longer have the joy of faith, she wrote, I am trying to carry out its works.

It took St. Therese a year and a half to die. She never regained the joy of her faith and the consolations it had once provided. But she never stopped loving God either. She was living in the midst of what the philosopher Simone Weil calls “affliction”—an uprooting of life, in which God can seem entirely absent. “The soul has to go on loving in the emptiness,” Weil writes, “or at least to go on wanting to love, though it may only be with an infinitesimal part of itself. . . . If the soul stops loving it falls, even in this life, into something almost equivalent to hell.”3

Christ loved like this on this cross, Weil says. The one “whose soul remains ever turned toward God though the nail pierces it finds himself nailed to the very centre of the universe.”4 This, Weil writes, is the place where the arms of the cross intersect; it is the true center of the world; it is God.

This is where Therese Martin, 23, 24 years old, lived for the last year and a half of her life. Nailed to the center of the universe, with her face turned toward God, she remained determined to make her whole life, up until her last living breath, an act of love.

Now St. Therese’s “little way” no longer seems so little. I even have a renewed appreciation for her Christmas conversion. Yes, it is a story about growing up, about maturing, about moving from an exclusive focus on oneself and one’s feelings to noticing the effect of one’s choices on others, to putting the feelings of others before one’s own. Yes, and what better definition of conversion could there be? And how had I ever thought that this was a simple change in her life, that it had nothing to do with holiness? That only shows how much I need to be converted.

St. Therese’s “little way” is cherished by millions of people around the world because it is a way of holiness that anyone can pursue. Seeking to make every interaction, no matter how ordinary, an opportunity to love more deeply, she prepared herself to keep loving, even in the face of doubt and suffering and death. Her little way invites us all to take the small steps that make the big steps possible. In my hometown, we needed the courts to take a big step, to insist that we integrate our schools. But without the little way of children cultivating friendships on the playground, of black parents and white parents choosing to send their children to integrated schools, it would have been hard for the big changes of those years to take root.

When I visited my parents the next summer, the old copy of St. Therese’s autobiography was back on my dad’s shelf in his study. (Where had it been last summer? Only God and St. Therese know. Maybe it had been there in front of my eyes the whole time, and I just couldn’t see it.)

It has my dad’s name in the front, and also mine. And it has some underlining that is most definitely mine. I turned every page to see what had struck me when I was 12. I laughed out loud to see my unsteady pencil marks underneath the words “Martyrdom was the dream of my youth. . . . I would die flayed like St. Bartholomew. I would be plunged into boiling oil like St. John . . . With St. Agnes and St. Cecelia, I would present my neck to the sword” (193). I laughed because I am the person I know least likely to seek martyrdom, or to want to suffer in any way, for any reason. I have no memory of desiring this as a 12-year-old. What did I love here? Why did I mark this passage? It’s her passion, I think, her desire to do all for God—to leave nothing out—that I think I loved.

There were a few other passages underlined or marked, mostly passages with lots of exclamation marks and italics. But there was one passage that stopped me in my tracks. In the back flap of the book, I found the words “page 87” written in my handwriting. And when I turned to page 87, I saw underlined in heavy pencil these words: “I felt it was far more valuable to speak to God than to speak about Him, for there is so much self-love intermingled with spiritual conversations!”

I felt it was far more valuable to speak to God than to speak about Him, for there is so much self-love intermingled with spiritual conversations.

I felt that I was receiving a message to my middle-aged self from my 12-year-old self, or perhaps a message from St. Therese herself. There’s not a single bit of italics anywhere in that sentence (although there is an exclamation point), but I felt it as if every single word had been italicized. Being in the religion business, I spend a lot of my hours and days talking about God and having “spiritual conversations.” But how much time do I spend speaking to God? How much time do I spend in prayer? I heard those two young girls—myself as a child and Sister Therese of the Child Jesus—ask me: Don’t you remember? Don’t you? Hand in hand—in cahoots, even—they whisper the word that Therese knew was at the heart of everything: love. More love.

Stephanie Paulsell is Houghton Professor of the Practice of Ministry Studies at Harvard Divinity School. She is the author of Honoring the Body: Meditations on a Christian Practice (Jossey-Bass). This essay will be included in the forthcoming collection Reflections on the Spiritual Life, edited by Allan Hugh Cole, Jr. (Westminster John Knox).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

I was rereading Praying with Theresa of Lisieux (Joseph Shmidt), struck with her vibrancy, cheekiness, intensity, and then- so young- her afflictions pulling her into a radical self awareness, eclipsing all but her faith in God, she becomes compassion itself, alone, suffering, invisible, – as on the cross. She reminded me of Simone Weil! They both have the audacity of brilliant children- full of life and spirit, and yet plunge ‘ beside themselves’ into awareness:the suffering servant permeates them. They are themselves as they Were,- all gifted, and even knowing themselves loved, plucked up by God, in the midst of their horrible afflictions- bodily and psychic. I loved your essay.