IN REVIEW

Poets on Hymns: “Silent Night”

By Jason Gray

What do you do when your organ is broken? In Obendorf, Austria, newly split from its sister city across the Salzach in Bavaria, it’s 1818 and the Napoleonic Wars have left their mark. It’s cold and damp and Christmas is approaching. Father Joseph Mohr is the new priest at St. Nikolaus and requests Franz Gruber (no relation to Hans) write a melody for the poem he’d written two years earlier. Gruber is the schoolmaster and the organist, but there is no organ. Silent pipes. Gruber plays the only instrument at hand, the guitar.

Arguably the most well-known Christmas carol ever was written out of necessity.

At least that’s how the story was told to me by another member of Central Presbyterian Church, an adult I was playing guitar with in the church’s contemporary music ensemble—two guitarists, a bass player, and the organist on a Casio keyboard. I was getting very involved with the church at this point in my life, in high school. I was active with the youth group, joining the choir, and showing off my new guitar skills in our nascent contemporary music group. We weren’t megachurch-ready, but we had a certain charm. My faith was growing, to be sure, but I was also in love with pretty much every female member of the youth group in some way or another. I was sure I’d marry one of them (I did not). This is probably why church has never seemed so enthralling as it once was, but I think almost everything is that way—nothing seems to matter as much as it did in high school. I recognize this is not a great reflection on my faith.

The story’s reason for the problematic organ varies, from mice chewing on wires to rusty pipes to simply choosing a well-made guitar over a low-quality organ.

The guitar is portable, but doesn’t have the largest range. It is quiet and no match for the organ’s volume. But if you want space in between your sound waves, if you want each note to have its own life, it will give it to you.

Although, you rarely hear the song performed in its original arrangement.

Bing Crosby’s recording of “Silent Night” (full orchestra and choir) is the third-bestselling single of all time with around 30 million copies sold. (His version of “White Christmas” is first on that list—need we any more proof that we are a secular people, despite our many protests?) That album of Crosby’s, Merry Christmas, with just a headshot of him wearing a Santa hat and a holly bowtie—my family wore that out on Christmas mornings. And I continued to do the same as a grown up, from magnetic tape to lasered plastic to digital files, always around the time the toilet paper from Mischief Night began to disintegrate from the trees.

I whistle and hum carols pretty regularly throughout the year (most likely “Winter Wonderland” or “Rudolf”). This surprises most everyone I come in contact with, but I’m not sure why. Yes, it’s out of season, but they are eminently hummable tunes, and how many of us in the Western world grew up hearing them more than any other class of song? “Silent Night” is not one I whistle though. It is one of the more somber tunes of the season (but not the most somber—I have to give that to “In the Bleak Midwinter”).

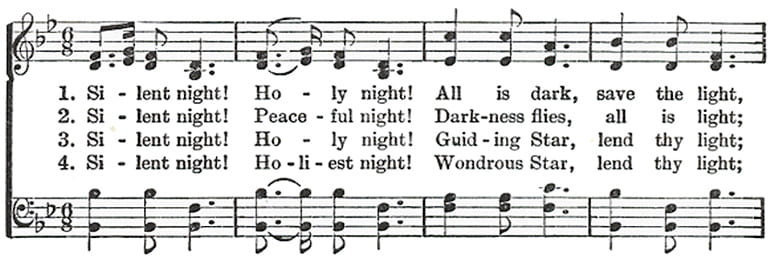

“Silent Night” is Joseph Mohr’s only hymn translated into English, and it is Gruber’s only still-known melody, though he reportedly wrote over a hundred. The Presbyterian hymnal includes four verses, but the fourth is an anomaly—it does not correspond to the original German text or the J. Freeman Young translation.

Americans sing the song out of order. Also incompletely. The original German hymn is six verses, but most of us know only three—the first, the sixth, then the second. Which seems like a good metaphor for me as a Christian, incomplete and out of order (perhaps all of us, but I won’t speak for everyone).

In the English version’s missing verses, we don’t sing about the salvation and mercy brought to us, the capital-F fatherly love, the fact that it was all planned from the beginning. The original German text narrates the story in the three lines between the refrains that bookend each stanza. We focus on the couple, mother and child, and the shepherds, and then again the baby—the people in the story. Whether intentional or not on the part of J. Freeman Young, the translator, I think there’s a good idea there. The intangible, though wonderful, things we hope are part of this story are stripped away, leaving us with what we actually know is there. The people. I don’t mean to be sacrilegious; only to suggest that the winnowing down to the human elements perhaps contributes to the carol’s importance to a great deal of the world.

At midnights throughout the Christian world the tune rings on as lights go down and candles burst to life. My favorite moment in all of liturgy is that moment the organ stops in the song and leaves only the congregation’s voices singing. For one moment, at least, the world around you is still. All that would follow from that one night in Bethlehem. A man who would inspire a dozen, then dozens, hundreds, thousands, millions, to turn the other cheek, to build houses for the destitute, to stop a battle for one day, to love one another and die, but also to force others to accept him, to kill for his rejection. This is the mixed blessing of Christmas, or perhaps the mixed inheritance—the blessing may have been pure, but not always its interpretation.

Franz Gruber made the best out of what he was given. I don’t know if I can say that about myself, or how many of us can. But it is what I think about when I hear “Silent Night.” When your organ is broken, find another way of making music.

Jason Gray is the author of Photographing Eden, winner of the 2008 Hollis Summers Prize. His poems have appeared in Poetry, The American Poetry Review, the Kenyon Review, Literary Imagination, Poetry Ireland Review, and other places.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.