In Review

Poets on Hymns: “One Bread, One Body”

By Kate Daniels

I grew up in the authoritarian framework of the Southern Baptist Church, and when I was a girl, my understanding of the world depended upon a cooperating pair of dualities.

The Simplicities were teachers, charged with passing along a very simple, either-or set of rules. Do this. Don’t do that. They concretized themselves in God’s word, the Bible.

The Authorities were cops. Guard dog–like, they dominated every aspect of my life as a child and assumed physical reality in the adults who surrounded me in my family and my church. Their job was to enforce the rules.

You could say it was not a capacious theology, dominated, as it was, by a single subject: sin. Capital S. Capital I. Capital N. Past, present, and future sin. We were born in sin we could never slough off. We were constantly being caught in the act of sin. We were relentlessly reminded to refrain from sin. Church was a place where it was never possible to forget how narrow was the road to God’s grace, and how unlikely it was that a sinner such as I would be able to follow it to the ultimate reward. Even now, I can hear the syncopated rhythm that every Baptist preacher I ever listened to belted out. In my head, it translated into something like tom-tom drums: SIN – sin – sin / SIN – sin – sin / SIN – sin – sin . . .

Although this doctrine had produced generations of simple-hearted, loving, hardworking Christian people in my family, it was, for me, an unfortunate frame of religious belief to have been born into. I was a devout and God-loving child, but I had the sensitive, language-oriented temperament of a future poet. I was introverted and private, with a highly reactive brain chemistry that rendered me vividly imaginative but left me overly sensitive to impingements. Exposure humiliated me. Disapproval scourged me. Fear flayed me. Beauty flattened me. Sitting in church, I felt bathed in klieg lights that shone nonstop on all my inadequacies.

I longed—without being aware that I longed—for a way to worship aesthetically, to express my complicated and passionate feelings about God in modes of communication not ordinarily used in everyday life. Outside, the church preached separation and hierarchy. But inside, God felt all of one piece, a huge, unruly front of affect that moved through me like weather, all-consuming and mysterious. In church, where I was obliged to sit still and affectless through long worship services, all dressed up and cramped inside “Sunday clothes,” I could not make the inside and the outside fit together.

Sometimes, music—the great old-time gospel hymns of the Baptist church—provided a temporary respite. My paternal grandmother was born in 1898 on a farm in Tidewater Virginia. Generations of her family were buried in the same Baptist churchyard in New Kent County. Although my Gran was only minimally educated, she had a natural ear for music. One of my earliest memories is of sitting alongside her in a metal glider on the front porch of her small home just off Route 1 in Southside Richmond. Her life was hard, and her faith was simple. Picking out hymns on an old guitar and singing along in a quavering, top-of-the-register voice seemed to help her cope. It was she who first introduced me to the hymns I would later sing in church: “Bringing in the Sheaves,” “Rock of Ages,” “Amazing Grace,” “Just as I Am,” “What a Friend We Have in Jesus.”

Because it made her happy, my younger brother and I learned to sing my grandmother’s hymns. Later, we sometimes performed as a duet in church on Sundays. On those occasions, my father drove into town to fetch my Gran and bring her to services so she could hear us, dressed up in our Sunday best, huddled together over a shared hymnal in front of the church. I am sure my spirit must have soared a bit as my brother and I combined our voices in our sibling harmonies, singing the hymns our grandmother had taught us. What I remember of those occasions, however, was the quaking fear of making a mistake—up there in full sight of God, the pastor, and the congregation—and the punishment that would surely follow.

I was ten years old when I first attended a Catholic Mass. It was February 1964, and my mother’s friend, Trula, whose family we were visiting in Florida, took me along with a passel of kids. Fifty years later, I can still recall many details of that first Mass—what the church looked like (palm trees outside, traditional cruciform inside), where we sat (second pew on the left), how the light fell in through the stained glass, the intriguing fact that all the women and girls wore hats or bits of lace on their heads. I felt as if a thirst was being quenched, and I drank in those details over and over as I sat through the Mass with its unfamiliar language (Latin), its inventory of paintings and sculptures and candles and flowers, and the heavy scent of incense that the priest had flung toward us as he processed down the aisle.

What was most deeply imprinted on me was the privacy in worship. For the first time, I felt completely safe in church.

I couldn’t have described it then, but what was most deeply imprinted on me was the privacy in worship. For the first time, I felt completely safe in church. Rote prayers were either silent, or recited together—not improvised as they were at home. Worshippers sat and stood together, as we did, but they also periodically moved their bodies in interesting ways, genuflecting, thumping a gentle fist over their hearts, bending down, all in a noisy herd, to lower the kneelers. In my church, we kept our hands in our laps and to ourselves. But at Mass, people’s hands moved in all kinds of interesting ways, making the sign of the cross, fingering rosaries and crucifixes. Sometimes they raised these things—which looked like jewelry to me—up to their lips and kissed them! As imaginative as I was, I had never imagined kissing in church.

The elders of this church were all men, just as they were in mine, but these men were androgynously clad in long gowns instead of suits and adorned with gold sashes and tasseled belts. They flung about pots of incense, washed their hands daintily at the altar, and were served by a retinue of altar boys. They did not thunder at us but murmured softly in a foreign language, almost as if we weren’t necessary to what was going on. For the most part, they left us alone with our thoughts. I was stunned when the entire congregation rose up and went forward to receive the Eucharist, to claim for themselves the gift. Back home, we waited passively for one of the deacons to pass us our homely bit of Wonder Bread and single sip of Welch’s grape juice. Here, the bread was a thin and elegant wafer, drawn forth from a gold chalice, and the blood was bitter-tasting real wine.

After that first Mass, I continued to attend Baptist services with my family. With a new model of worship in my mind, however, I chafed at its familiar strictures. By the time I was 14, I found more and more excuses to skip church. At school, I filled in part of the gap by singing in choruses where much of our repertoire consisted of eighteenth-century sacred music. For what remained of my adolescence, I prayed privately, I sang, and I carried around in my head all those private feelings about God that did not fit. I often revisited in my imagination the experience of that first Mass where I felt both privately held and publicly affirmed while worshipping.

And then, just as the radical reorientations of Catholic worship instituted by the Second Vatican Council began to be apparent in the American church, I went off to college in Charlottesville, Virginia. There, I ended up in a suite of girls, many of whom were cradle Catholics from the Northeast. They astonished me by voluntarily attending Mass every Saturday evening. Weekly Mass was built into their lives in a casual, comfortable way. It was something they did for themselves rather than something they did out of obligation. This was an unusual attitude for college students in the early 1970s, and I began to walk out with them on Saturday evenings to see what kind of church evoked such affectionate loyalty.

I found provocative the idea that a saint might be soldered together from junk.

That is how I came to the “new” Catholicism—a phenomenon that astounded me right from the start. I found it housed in a church building unlike any I had ever seen: a “church in the round,” a circular brick building, topped by a simple cross, and served by Dominican priests. To enter, you walked across an elevated walkway where a larger than life–sized sculpture of St. Thomas Aquinas had been installed. He was made entirely of chrome bumpers salvaged from junked cars. Never had I seen such art in church: discernibly figural, but also abstract. I found provocative the idea that a saint might be soldered together from junk.

These Saturday evening guitar Masses astonished me with their informality and quickly obliterated my old ideas about attending church. At St. Thomas, many of the students arrived with bare feet and in patched blue jeans. They sat cross-legged on the floor before Mass, playing guitar, chatting, and laughing. Sometimes if you arrived early, a gallon bottle of cheap wine might be passed around. Afterwards, we gathered in the vestibule for potluck suppers. Back then, God-hungry, and trying to find my way into a new form of worship, I was enthralled by the invitation to be myself, private and dressed down.

Because “One Bread, One Body” was not written until after my time at St. Thomas, it could not have been there that I first heard it. Still, my association between that church and that hymn are very strong, and I believe that my early experiences of Catholic worship in the humble space of St. Thomas set the stage for my encounter with this very simple hymn, which has come to mean more to me than any other.

Like the new church-in-the-round architecture, “One Bread, One Body” comes directly out of the Second Vatican Council. Under its directives to maintain “noble simplicity” in all church matters, but with permission to respond to the “local traditions” of individual parishes, Catholic worship radically reimagined itself. Priests turned around to face their parishioners, women removed their head coverings, and vernacular languages replaced the worldwide use of Latin. In St. Louis, a group of young Jesuit seminarians collaborated on liturgical music for a new era. They modeled their hymns on popular forms like folk music and easy listening, and composed them for acoustic guitar. Accessible, musically stripped down, and closely tied to scripture, “One Bread, One Body,” composed by John Foley in 1978, is a good example of the work of the St. Louis group, as they came to be known. Together, they created a series of accessible new hymns, including “One Bread, One Body,” that have become iconic elements of Catholic worship in our time. Others included “Be Not Afraid,” “The Cry of the Poor,” “Though the Mountains May Fall,” “Earthen Vessels,” and “Here I Am, Lord.”

The scriptural reference of “One Bread, One Body” is from 1 Corinthians 10:16–17:

The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the body of Christ?

For we being many are one bread, and one body: for we are all partakers of that one bread.

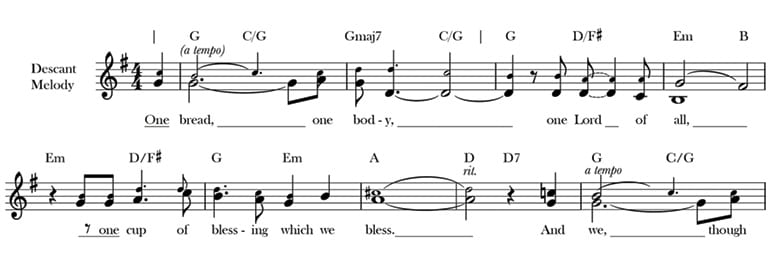

It’s a short hymn with a haunting tune and simple lyrics that barely proceed past the scripture.

Here is the refrain:

One bread, one body,

one Lord of all,

one cup of blessing which we bless.

And we, though many,

throughout the earth,

we are one body in this one Lord.

Made mostly from nouns and prepositions, and the verb to be, the hymn’s lexicon is confined to one and two syllable words. If there is an adjective present, it is the word one, used repetitively to modify the bread, the body, the blessing, the Lord. It’s hard to miss the point: One is the answer. One word, one syllable, one cup, one Lord, one church, one body of Christ which encompasses the entirety of humanity even as it cradles each of our individual selves.

It’s hard to miss the point: One is the answer. One word, one syllable, one cup, one Lord, one church, one body of Christ.

But this simplicity is also baffling. The image at the center of the hymn is its “cup of blessing”—easy enough to understand and imagine. Handed to us, we drink from it. But what does it mean for us, as mortals, to bless the God-given cup of blessing? Reciprocity of grace was not in the top-down theology I learned in my early life. I don’t think it ever occurred to me that I might have it within me to confer a blessing upon another. One of my favorite parts of the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA) was the ritual in which my sponsor—an ordinary human like myself—blessed me over and over, anointing my head and heart, my hands and feet with oil.

From the first time I sang this hymn in Mass—it would have been in Baton Rouge in the 1980s—I felt mystically drawn into something larger than myself—a delicious vastness within which I experienced myself as part of a whole, but also decidedly separate. I call this now the Body of Christ.

There are so many ways to God. “One Bread, One Body” has helped me to understand that. My family members found salvation and sustenance in forms of worship that constricted my spirit. The joy my loved ones found under plain white steeples was inaccessible to me. Nevertheless, we remain together in loving communion within the Body of Christ, a fact I celebrate whenever I sing “One Bread, One Body.”

On Sunday mornings when I can’t go to Mass, I like to watch YouTube videos of “One Bread, One Body.” The iconic version in its original guitar form is the one that pops up most often, but there are lots of variations. A gorgeously gowned Methodist choir all lined up at the front of their church in Minnesota. Ordinary parish Masses all over the world. An all-Filipino choir at Holy Rosary Church in the middle of the desert in Qatar, performing a beautifully harmonized version. Watching the different interpretations of this simple hymn with its haunting, deconstructed melody and its unpretentious lyrics is always moving to me.

One of the videos of “One Bread, One Body” that I particularly love is filmed from behind the altar at Epiphany Church in Gramercy Park, Manhattan. It is first communion. The camera captures the priest’s familiar movements as he prepares the gifts. Over his shoulder, just past the altar, you can see the congregation stretching out. While the priest is overseeing the Eucharistic miracle of transubstantiation, some people may be barely paying attention. They’re whispering and waving to each other, or sending a clandestine text message from a phone concealed in a pocket, or writing in their checkbook the amount they just dropped in the offertory basket. Congregants are constantly flowing in and out of the sanctuary. Everyone’s body language is casual and free. At the back of the church, a standing woman rummages at length in a huge shoulder bag, and over on the side, a man sits with his arms clasped behind his neck, elbows soaring out from his body like butterfly wings.

The space inside the Catholic Mass for human beings to be what they are—human, necessarily imperfect and messy—continues to compel me.

The space inside the Catholic Mass for human beings to be what they are—human, necessarily imperfect and messy—continues to compel me. Sometimes the suppressed Protestant inside me rises up, pursing her lips. I no longer do this with judgment, I’m glad to say, but with a kind of inner laugh. This is what “One Bread, One Body” represents for me—a praise song for a God who looks at us all with a forbearing and humorous nature. One who blesses us all, and leaves us alone much of the time to work it out by ourselves. Sometimes mistakes are made, but they are never fatal, though they may seem so in the short run. For God’s time is not our time, and our Catholic faith offers us a multitude of ways—an overflowing cup of blessings—to correct our failings.

Once, attending Mass in Durham, North Carolina, alone with my three young children, two of them still in car seats, all hell broke out between them over a Ziploc bag of Cheerios that had been consumed earlier than I’d calculated. Struggling to restore order to our caterwauling corner of the pew, and horribly anxious about the raucous spectacle we were making, I was distracted by a touch on my arm. An older woman was leaning toward me, gesturing toward my misbehaving kids. She looked very much like one of the churchwomen of my childhood, all dressed up in Sunday clothes, and I tensed up, anticipating a rebuke. Then I saw she was smiling. “Don’t worry, sweetie,” she said. “We’re just glad you’re here.” The relief that swept through me at her words was a giant cup of blessing. I gulped it down. In my head, I blessed her back. When I was able to tune in to the Mass again, the gifts were being prepared, and the parish music minister was instructing us to turn to #498 in Glory & Praise so we could sing, together, “One Bread, One Body.”

Kate Daniels is a professor of English and director of creative writing at Vanderbilt University. She was born in Richmond, Virginia. She has received a number of awards and prizes for her poetry, and she has become a leading voice for the use of art in medicine.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.