IN REVIEW

Poets on Hymns: “Jesus Is All the World to Me”

By Patricia Jabbeh Wesley

War has its own music. It rises out of the explosion of bombed buildings and missile attacks, in the bombardment of early morning gun battles between warring factions, in the ominous sounds of crumbling cities, and in the shrill cries of the dying or soon to be executed. Such horror makes every organ in us tremble, that senselessness of human cruelty which is as inexplicable as an insane language. For me, a poet, this horror turned me even more to hymns, to songs and poetry, and especially to the old, solemnly powerful hymns my Mamma sang in our home when I was a child. In the ugliness of the Liberian Civil War, the starvation, desperation, and constant fear of being killed, I rediscovered the power of the old hymns. Everything else had failed us, so I needed to help my family find that old place of peace.

One day in May 1990, as war engulfed our country, I pulled one of our old family hymnals off a bookshelf and began to leaf through it. The news on the BBC radio was clear. Tens of thousands of rebels led by Liberian warlord Charles Taylor were drawing closer to Monrovia, our capital. They were fighting a guerrilla-styled war against Liberian government troops. Samuel K. Doe, the president of Liberia, was losing the battle every day. His army, therefore, turned on us civilians and, like the rebels, were also killing thousands of civilians throughout the country and across Monrovia and its suburbs.

The invading rebel army called itself the “National Patriotic Front of Liberia,” or NPFL, but we civilians called them “rebels.” They also nicknamed themselves “Freedom Fighters,” but we knew that they were guerrillas, looters, killers, and rapists. The news of the bloodbath and the devastation of our cities and villages on their way to Monrovia defined them and their rebel warfare for us.

Charles Taylor and his forces invaded Liberia from a northern border town in Nimba County on Christmas Eve, 1989. By May 1990, they’d already captured most of the country in their mission to remove the Liberian government, and they were moving fast toward the capital city where we lived. They’d leveled many cities and villages, and now foreign governments, including the United States, were evacuating their citizens from Liberia. There are no words to describe the desperation of a nation preparing to be overrun by such a powerful and unruly rebel army as the NPFL. Nor are there words to describe the aloneness we felt as the world suddenly abandoned us. In that same month of May, Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia suffered a breakup and split into two warring factions, becoming the NPFL and the Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia, or INPFL. The original NPFL was now at war to remove the Liberian president, Samuel K. Doe, and his government, even as they were locked in a fierce war against their breakaway group, the INPFL. The new rebel group, INPFL, led by Taylor’s former fellow co-commander, Prince Y. Johnson, was also caught up in a similar fight on two fronts, against Taylor and Doe.

All of this news was so overwhelming that I started writing poetry with a new dedication, writing about the encroaching war. But not even poetry could comfort me at this time. I felt that our family needed something else to hang on to. We were devout Christians who held family devotions every morning and evening, teaching our children the values of Christ. Therefore, it was not difficult to think of needing a theme song or a hymn for our family. I thought we needed a song we could hide in our hearts if we were forced to flee the city.

The hymn would become my favorite during the war. Singing it in the privacy of my bedroom one day as the war drew closer, I knew that this was the hymn for my family.

I sat on our terrazzo-tiled living-room floor that day and found Will Thompson’s “Jesus Is All the World to Me.” The hymn would become my favorite during the war. Singing it in the privacy of my bedroom one day as the war drew closer, I knew that this was the hymn for my family. I used to know the power of such old hymns as a little girl growing up in my mother’s church during the 1960s. Even as a little girl, I was drawn to them, as I was to poetry. Maybe I loved them because Mamma sang them out loud throughout the house when she was down. Maybe I loved them because they were my first contact with poetry. I had memorized many of them as a child, held them in my heart, and believed in their power. This was the old place of peace, I thought, where I needed to take my family. This would be our healing.

When the war began, on December 24, 1989, I was a young wife and mother of three small children, living with my family in Congo Town, a suburb of Monrovia. My husband, Mlen-Too, and I were on the faculty at the University of Liberia while volunteering to mentor and minister to university students throughout Liberia. As the war drew closer, we began looking for the tools we needed to help our family survive the carnage we knew was coming. We began making all those kinds of plans people who have never seen war think they can make. Our experience as Christian leaders in the community was important if we were to survive, we thought. By early June 1990, the rebels were only about thirty miles east of Monrovia, but much closer to our home.

What does one do when one’s country is being overrun by two powerful and unruly rebel groups at war with a disorganized government army? What does one do when one cannot go to work, go to the bank, or take her children to school? What does one do when “all other ground is sinking sand,” as fighters on all sides burn down villages and cities, killing tens of thousands, raping women and young girls, turning small boys into child soldiers, and bombing everything in their path? By mid-June, we were surrounded, on the land, at sea, and in the air, in one of the world’s most brutal civil wars. Troops loyal to Liberian President Samuel K. Doe fought hard, but they were fast losing the war. Already, tens of thousands of Liberians were dead. How would we survive the carnage? How could we survive? What would we take with us if we had to run and what would we leave behind? Would we take our hymnals, our Bibles, our books, our clothes, food, or would we be forced to run with only the clothes on our backs?

After I decided on “Jesus Is all the World to Me,” I quickly memorized all of the verses and gave the hymnal to my husband to do the same. Then, we helped our small children learn the words by singing the hymn in our daily morning and evening devotions. The children, Besie-Nyesuah, 7 years old then, Mlen-Too II or MT, 4, and my brother, Wyne, who lived with us, 12 years old, also needed to learn the song. Our third child, Gee, a boy, was only 8 months old, so, he only looked on as we sang the hymn over and over, along with other songs we also needed to memorize.

At first, the three children were slow to learn it, but soon they could sing one or two of the verses without looking in the hymnal. In addition to preparing our immediate family, we also needed to help my aging mother and her two teenage boys understand what we were doing. They had moved in with us due to the fighting. This was difficult, but soon Mamma was singing along. “Jesus Is All the World to Me” was not among her favorites, nor was she familiar with it. She was a Pentecostal, whose old-time favorites were songs like “What a Friend We Have in Jesus,” “When We All Get to Heaven,” and “There’s Power in the Blood.”

There is something powerful in a hymn that confirms our hopes and belief in the God who is not only our Lord in a time of peace, but also in a time of war.

The words of the hymn took on new meaning for me as my family and I journeyed through the war. There is something powerful in a hymn that confirms our hopes and belief in the God who is not only our Lord in a time of peace, but also in a time of war. I examined the words of this great hymn like a poet examines the lines of her own poem before publication. I explored the words as they became one of my weapons on our painful journey. I studied the words as though they were the gospel that I needed to carry me through the long military roadblocks, the horrors of walking through the jungle with my family as we fled our home on August 1, 1990, through the intimidation from the rebels and government soldiers, on our long walk into Charles Taylor’s rebel stronghold to flee the fighting that would break out in our neighborhood a week after our flight. I was the custodian of what I knew as our hymn so my family would stay strong.

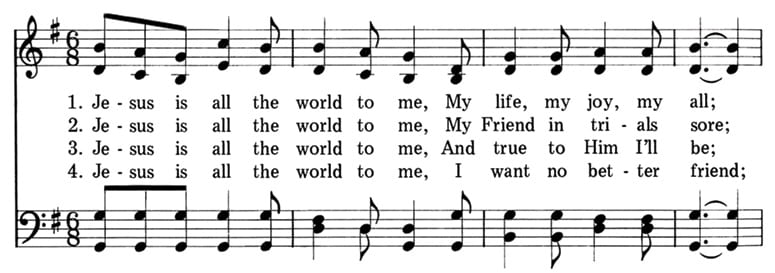

“Jesus Is all the world to me / My life, my joy, my all / He is my strength from day to day / Without Him I would fall. / When I am sad, to Him I go, / No other one can cheer me so; / When I am sad, He makes me glad, / He’s my Friend,” we sang. If Jesus was all the world to me, and if he was my life, my joy, my all, then it did not matter whether I survived the war or not, whether my family survived or not, whether we starved to death or not, I told myself daily. But it was also important to know that, because Jesus was all the world to me and because he was my friend in this time of tremendous pain, he would keep my family safe. He would be our strength, our hope, our fortress, the one and only one who knew us in our deepest pain and in our greatest joy. I took every word and every line and every verse to heart and claimed it as I did many other hymns. If my world was falling apart, if my world was devastated, as it now was in 1990 and 1991, through the violence, as we were tortured and as we faced death every day, then there was nothing to worry about as long as “Jesus was all the world to me.”

The power of a hymn, whether one is a poet or not, is rooted in faith and in the belief that we have a God, the creator of the universe who gave his all for us on the cross. This hymn explores that faith. As a Christian, my faith in the Bible’s validity and in the truth that Christ brings helps me believe in the power of the words of that hymn. When Will Thompson wrote, “I trust Him now, I’ll trust Him when / Life’s fleeting days shall end,” I claim the words for myself. These words are more meaningful to me than the words of my own poems could ever be. Yes, I have written poetry that explores my painful war experiences, and many of my poems can bring an audience to tears when I read. But the words of a hymn carry more power than that. There is that sacredness in the words of a hymn that is more powerful than the words of a poem. Words like “Jesus is all the world to me, / My Friend in trials sore; / I go to Him for blessings, and / He gives them o’er and o’er” are based on the Bible, and we Christians believe in the holiness of the Bible. It is that faith in both the hymn and the Bible of the hymn that sustained my family and me through the Liberian Civil War. That faith gave us hope that there is a great God, the overcomer, who makes all wars cease, the one that the songwriter of the hymn proclaims, the God who gives grace to the desolate refugee of war. Jesus is all the world to me.

Patricia Jabbeh Wesley is an associate professor of English at Penn State Altoona. A Liberian Civil War survivor, she is the author of five books of poetry, including When the Wanderers Come Home (University of Nebraska Press, 2016), Where the Road Turns (Autumn House Press, 2010), and The River Is Rising (Autumn House Press, 2007). She also authored a children’s book, In Monrovia, the River Visits the Sea (One Moore Books, 2012).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.