IN REVIEW

Poets on Hymns: “I Love to Tell the Story”

By Kathleen Norris

When I was a child I thought my family went to church in order to sing, an easy assumption as my father was a choir director and I made my debut in a “cherub choir” at the age of four. Later, as I prepared for confirmation, I discovered that the catechism made less sense to me than the hymns I sang on Sunday morning. That’s where the poetry was, and theology in a form I could understand, that enticed me on an emotional level.

The hymns I cherish most are those that combine good theology with graceful verse. “Come Down, O Love Divine,” for example, with its submission to the workings of the spirit: “O let it freely burn, till earthly passions turn to dust and ashes in its heat consuming.” I feel a pang in admitting that “the yearning strong, for which the soul will long, shall far outpass the power of human telling.” As “human telling” is what I do, those words can be painful, but they also heal, tempering my pride.

I once used a hymn to help heal my husband. Raised a Catholic before Vatican II, he had a strained relationship with the Christian faith. He knew Reform theology—he’d read more Calvin than I had—but wasn’t familiar with Protestant hymns. When I was preparing a worship service for a Presbyterian church in western South Dakota, where I would be preaching, I chose a hymn, “Immortal, Invisible, God Only Wise,” with him in mind. I’m not sure my poet husband heard a word of my sermon, but after church he raved about that hymn. He recognized it as a perfect poem, by Coleridge’s definition, “the best words in the best order,” with its evocation of God as “Unresting, unhasting, and silent as light.”

As a Benedictine oblate called to daily remind myself that I am going to die, I treasure this hymn’s realism: “We blossom and flourish like leaves on the tree, then wither and perish, but naught changeth thee.” This verse holds more meaning for me as I’ve grown older and so many of my loved ones, including my husband, have died. The hymn ends on a mystical note about our limitations in comprehending the divine: “All laud we would render, O help us to see, ’tis only the splendor of light hideth thee.”

I find that the best hymns are like scripture in that their words strike my heart when I most need them. If I’m experiencing spiritual dryness, the honesty of “Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing” is a balm. “Prone to wander, Lord, I feel it; prone to leave the Lord I love.” Oh, yes: preach it, brother. And when I was preparing a funeral service for my sister Rebecca, Isaac Watts’s magnificent version of Psalm 23, “My Shepherd Will Supply My Need,” came to mind. Brain-damaged at birth, my sister had an exceptionally difficult life, and the closing verse, with its promise of being “no more a stranger, nor a guest, but like a child at home,” seemed right.

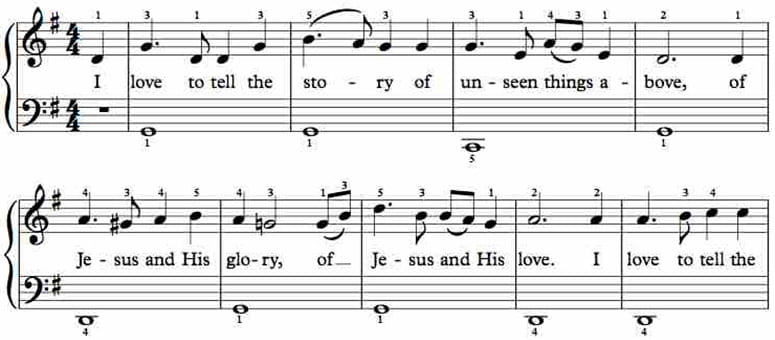

I’d call “I Love to Tell the Story” my favorite hymn for two reasons: its simplicity, and the fact that “I love to tell the story” could be any writer’s mantra. The hymn is apparently too simple for the Episcopal hymnal, which is ironic, as its author, Katherine Hankey, was a member of the Clapham Sect, a nineteenth-century group of evangelical Anglicans devoted to ending slavery. My copy comes from a Presbyterian hymnal.

I appreciate the line, “those who know it best are hungering and thirsting to hear it like the rest” as a challenge. Any writer knows the value of repetition, but here it is deemed essential to a faith that can never be fully grasped or mastered. All we can do is listen to the story once again, and allow it to become fresh and new.

Even as a child I was attracted to this hymn’s insistence on the vast import of story: the idea that hearing and telling Bible stories involved me in something much larger than I could comprehend, that transcended time itself. And this makes the hymn’s last verse difficult for me to sing without weeping: “And when in scenes of glory, / I sing the new, new song, / t’will be the old, old story, / that I have loved so long.”

One of the miracles of people singing hymns together is that they can transform even a drab hotel conference room into a bit of heaven. This hymn asserts that heaven is indeed full of singing and encourages me to envision all the people I have loved being with me there and joining in. And we’ll discover that the new song we’re singing is the gospel in a nutshell, that “old, old story, of Jesus and his love.”

Kathleen Norris’s books of poems and essays take a wide view of Christian practice. Raised in Methodist and UCC churches, currently she is a member of a Presbyterian church in her mother’s hometown in South Dakota, a member of an Episcopal church in Honolulu, and an oblate of a Benedictine monastery in North Dakota.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.