IN REVIEW

Poets on Hymns: “Great Is Thy Faithfulness”

By Kwame Dawes

“Great is Thy Faithfulness” is a “classic” hymn in the sense that it is in the style of nineteenth-century hymns in its language and musical form. Until I decided to write this piece, I had never even thought for a moment about who wrote the song, where it came from, and what it might have meant to the person who composed it. I selected it because, when asked to pick songs for any important occasion in my life and in the life of my family, I have always picked this song.

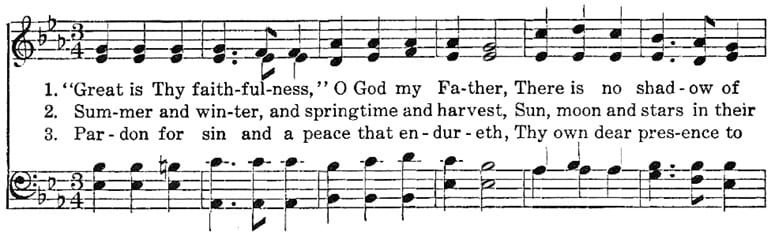

I have always picked it because it has consistently articulated my sense of gratitude for the things that have gone well in my life and in the lives of those that I love. It is fundamental and basic in its doctrine of salvation. If I claim to be a Christian, which I do, then this song does the work of laying out the character of devotion and submission to God. It presents the core argument of the faith, and it lends itself to repetition. It is a hopeful song. In the manner in which I remember it, the final verse is always joyful, especially when it moves toward the affirmation of the chorus. And musically, the chorus is perfectly memorable. Indeed, the way that it rises to its triumphant repetition, and the sweet spot of “thine hands have provided . . . ,” which begs for harmonies of rich depth and complexity, makes it hugely affirming and uplifting as great hymns should be. The “argument” of the song is basic. As an apologia, it presents the case for the claim that the chorus presents: “Great is thy faithfulness, Lord unto me.” Each verse is an argument, and the chorus affirms that argument. So, when the final verse declares, “blessings are mine with ten thousand besides!,” it makes sense to then fall into the almost militant and joyous declaration, “Great is thy faithfulness!” The waltz meter is elemental to this song’s character and its shape.

It is a curious thing to me that I did not select a song that has demonstrated a flexibility such that it has been allowed to be rendered in different musical styles that mean a great deal to me. There is no reggae version of the song that stands out to me, nor is there a highlife version of the song that sticks in my mind. Oh, I am sure that it has been rendered in many styles, but almost always, in Jamaica, the song is rendered in that deeply Victorian style, slow, steady, with the sense of the cathedral rising around it. And yet most of the times I have sung this song, it has been in small groups, impromptu gatherings, outdoors, and in the world of the Charismatic movement that raised me in Jamaica, decidedly anti-cathedral settings. In other words, I encountered that song during periods when the “hits” of worship were modern choruses, very contemporary and almost in defiance of the rituals of the established church. And yet, significantly, our leaders would somehow remember this gem, and in this new space, the song would assume great meaning because our ability to find in it the doctrinal and emotive familiarity of our faith proved to be central to its power and meaning. In a time when the great doctrine of the time among Charismatics was “what new thing is God doing?,” this old song would both unsettle us and move us for its age (and hence its unexpected freshness), its relevance, and its beauty.

“Great is Thy Faithfulness” is the song that is easily incorporated into all communal occasions, especially family occasions.

I chose this song because somewhere in our lives, my wife and I agreed that “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” is our hymn. There is a difference between what might be her hymn and what might be my hymn, and what proves to be our hymn. For instance, whenever I purchase a new pen, I almost always write the following words down: “When I survey the wondrous cross.” I wouldn’t call this a favorite, but I would call it a song of importance to me, for it spells out with explicit clarity and some skill the fundamental tenets of Christian salvation. But “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” is the song that is easily incorporated into all communal occasions, especially family occasions. Part of the ritual of the life that my wife and I have established as a family has been the affirmation of the various ways in which we have seen grace in the providence of our lives. We have had hard times, times of need and want, times where death lurked in the shadows, times when we did not know what lay in the future, times, in other words, when we felt out of control. As immigrants we have experienced that the massive sense of stepping blindly into the unknown has characterized who we are and what we do, and so the faithfulness of God has been something we have easily felt the need to express gratitude for.

This hymn works for so many occasions. When my father died suddenly and tragically, the question was what to offer as songs for his funeral. My father was a Marxist, and while he never claimed atheism as a dogma, I still remember him quipping, “The ancestors I know, but J. Christ, esq., I do not know,” or something to that effect. But his children had all managed to reconcile their cultural socialism with a genuine and perhaps radical faith. My mother was a longstanding Catholic who had developed a more evangelical bent in time. And so we were fully aware that the funeral was both for him and for us. “Great Is Thy Faithfulness” made the list. It also made the list of songs for my wedding with Lorna, and Lorna and I have shared this song in any environment that has warranted the expression of who we are in the world in terms of our spiritual sense of the world and the grounding of our lives.

This song offers some of the key qualities for that curious combination of prayer and congregational affirmation. Theologians probably have a term for this, but in my mind, it is especially telling that some songs lend themselves entirely to almost closed prayer, while others speak in communal terms such that the “audience” for the song is the rest of the congregation. In this song, the audience is, first and foremost, God. The song addresses him. And the speaker is a singular speaker—it is the “I,” the “me.” Hence, the song makes sense to the evangelical mind—the mind that seeks to articulate an intimacy with the deity to whom one speaks. Yet the shared sentiments of the song, the shared awareness of what God’s faithfulness has ensured, is decidedly one of the critical ways in which the song becomes a communal one, one in which all the singers are at once affirming a deeply personal relationship with God and, at the same time, a communal affirmation of that relationship with those within earshot.

For a self-proclaimed roots man, a man who is acutely aware of the complexities of postcolonialism; and more than that, for a man whose embrace of Christianity was delayed for years because of the deep struggle I had intellectually and philosophically with the history of Christianity and its relationship with colonialism and slavery; and further, for a writer who has been explicit that reggae music’s capacity to engage what Kamau Brathwaite calls Nation Language, and to affirm an African sense of culture and identity, something does seem almost contradictory in this impulse toward a song that employs archaisms and a musical style and cadence that are decidedly Eurocentric.

The best I can offer is that those characterizations of self are as always limited and rarely reflect the contradictions and complications of our lives when the public self intersects with the deeply personal self. Further, there is little question that my movement to faith came about because of something that I could only call grace, which allowed me to discern in Christianity a series of beliefs and tenets that transcended (a word, by the way, that I use sparingly and with great caution) and, at the same time, that managed to accommodate the peculiarities of my distinctive existence, my discourse, my politics, my history, my fears, my anxieties, my education, and my sense of culture. At the heart of this transformation, this conversion, if you will, was a way of viewing faith that would later find language in a line by T. S. Eliot that I only really started to understand as being relevant to more than art in 1994, as I finished the last touches of my long epic poem, Prophets, which, arguably, could be read as the first serious effort to address my faith in the copious manner that I felt was needed at that point: “For us, there is only the trying, the rest is not our business” (“East Coker”).

“Great Is Thy Faithfulness” does not, I can say, have the kind of impact on my sense of the world that, say, Bob Marley’s “Give Thanks and Praises” has whenever I hear it. But I would never say that one is more important to me than the other. “Give Thanks and Praises” roots itself in the spirit of thanksgiving, of gratitude, and of appreciation.

And because Marley offers this song in a music that I feel owns me as much as I can claim to own it, I am constantly affirmed by what it does to my body, my mind, and my spirit. Yet, when I sing the final verse of “Great Is Thy Faithfulness,” I do find rolling through my mind a litany of the reasons for gratitude—some even deeply secretive—that I carry within me everyday, and so I can weep as I sing this verse:

Pardon for sin and a peace that endureth,

Thy own dear presence to cheer and to guide;

Strength for today and bright hope for tomorrow,

Blessings are mine, with ten thousand besides! . . .

I could easily have started this reflection with the statement, “I do not have a favorite hymn.” This would be true. But as I think of hymns that have meaning and value to me, I find that I am drawn to this great hymn. When I discovered the actual history of this hymn, I realized it does not lend itself to being an automatic preference of mine. The author, Thomas Obadiah Chisolm, was a rural southerner from Kentucky who lived through the period of Reconstruction and the difficult years that followed into Jim Crow America. He wrote this song in 1923 when he was in his mid-50s. It became popular immediately. Curiously, the language and style of the song are archaic and very nineteenth century, even though he wrote it well into the twentieth century. But what he actually wrote was a poem—one of the many he wrote during his lifetime. He certainly was not a modernist poet. William Runyan, a New Yorker who grew up and lived in Kansas, set the poem to music, and these two Methodists would produce a song that, quite frankly, they have become best known for.

Given the sketchy history I have at this point of these two men, I have decided against going any deeper. I fear discovering things that would make it harder for me to focus almost exclusively on the song in the manner that suspends the intellect and elevates the emotive. In other words, I don’t want to spoil the song for myself. I would be hard-pressed to describe this song and lyric as an example of great literary or musical achievement. While I am not qualified to make such a pronouncement on the musical achievement, I can say that, as a poem, it is at best competent and occasionally hackneyed. But it makes a case beautifully, in the way that the best sermons and speeches can make wonderful and moving cases. There is an art to this. What I can say is that, at the end of the day, the song manages to remain important to me because I have come to associate it with key moments of my life, and during those moments, the song has had the pure clarity and meaningfulness for which I remain deeply grateful.

Kwame Dawes is Chancellor’s Professor of English and editor-in-chief of Prairie Schooner at the University of Nebraska. Born in Ghana, he spent his childhood and early adulthood in Jamaica. A prolific and celebrated writer of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and plays, he also collaborates with musicians, filmmakers, and visual artists.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.