IN REVIEW

Poets on Hymns: “Come, My Beloved, to Greet the Bride”

By Yehoshua November

Narrow arches and walkways opening to private gardens, white linens on rooftop clotheslines, ancient stone synagogues, the holy Wailing Wall itself. When I was 18, I spent a year in the Old City of Jerusalem. I had just broken up with a girlfriend and graduated from a public school in Pittsburgh, the former steel-mill city whose working-class population idolizes the Steelers and Penguins. Now, I found myself in an all-male yeshiva, my dorm room only several hundred yards from Judaism’s most sacred site. Though situated at the heart of my people’s history, I felt far away, geographically and spiritually.

To be sure, I had grown up in a traditional Jewish home. We observed the Sabbath and followed Jewish dietary laws. But it was a home that placed equal—if not more—emphasis on the arts and secular culture. As I write in one of my poems, the Marx Brothers’ movies served as background to family dinners, and Sam Cooke’s sensual voice would float up from my father’s Danish speakers when he returned home after a long day of seeing patients. My mother was a student of art history. Biographies of artists lined our shelves, and impressionist prints hung on the walls. On road trips, my father played Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, The Drifters, Roy Orbison, and Marty Robbins (my first exposure to poetry).

Indeed, I had spent most of my life in Jewish day schools. I had even completed close to a year of studies in a yeshiva in Rochester, New York—a far more zealous institution than the school in Jerusalem, where students didn’t dress solely in black and white and were encouraged to attend secular universities. Still, on the cusp of adulthood, in a distant environment devoted exclusively to Judaic studies, I felt more keenly a tension I had always felt: the pull between the here and now and the spiritual afterlife, which, as the rabbis of my youth had so often underscored, awaits those strong enough to jettison their worldly concerns and devote themselves to Torah study. That year, I learned a few pages of a Talmudic tractate on marriage but also found a small used book store in the Jewish Quarter where I purchased The Brothers Karamazov, Jude the Obscure, and Malamud’s The Fixer. I also wrote the sort of bad poetry only a perplexed 18-year-old can write and did not fail to notice the young women from London attending a seminary around the corner from our yeshiva.

Every Friday night, as the sun set over Jerusalem, arms over each others’ shoulders, the students at the yeshiva danced down the long set of stone steps that led to the Western Wall, where we would pray the service that welcomes in the Sabbath. Our enigmatic head rabbi—a stocky man with a high-pitched voice—criticized this ritual as too demonstrative, an attempt to get ourselves photographed by the many tourists who’d come to visit the holy site. Perhaps he was right, but I remember these moments as a point of light and clarity in a confusing time. And as I danced with my classmates—many of whom I secretly resented for their profuse praises of the yeshiva staff and their readiness to dive into the Torah’s waters—I sensed a kind of peace wash over me.

This mystical poem—especially when read according to Hasidic thought—complicates the theology that sees this physical life solely as a means to a later spiritual reward.

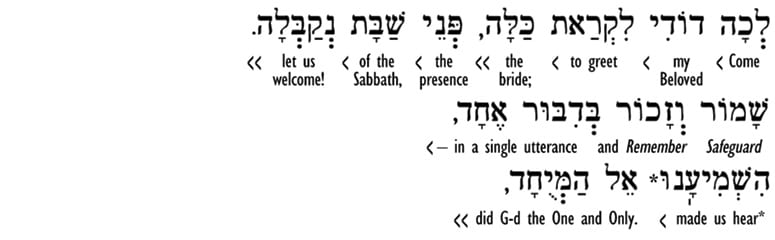

At the bottom of the steps we formed a circle and danced in front of the ancient wall whose cracks were crammed with desperate notes—scribbled prayers for healing, for an escape from poverty, for children, for finally finding the fated marriage partner. A classmate with a sweet voice would take his spot in the front of our group and begin to lead the Sabbath evening prayers. Soon, the sky overhead turned deep blue, and we sang the hymn that ushers in the Sabbath: “Come, My Beloved, to Greet the Bride. Let Us Welcome the Sabbath.” I didn’t know it at the time, but this mystical poem—especially when read according to Hasidic thought—complicates the theology that sees this physical life solely as a means to a later spiritual reward. As I hope to explain, the poem turns upside down a worldview that prizes the heavens over the divine possibilities of the everyday. And, for me at least, this reversal seems to run parallel to the tendency of many contemporary poets to locate transcendence and light not in the sublime moment but in the mundane.

Over the years, I’ve heard “Come, My Beloved, to Greet the Bride,” which likens the Sabbath to both a bride and a queen, put to many different tunes. (I even know of a rendition that uses Simon and Garfunkel’s “Scarborough Fair” as its melody.) The lyrics, however, were composed by a sixteenth-century Kabbalist and rabbi, Shlomo HaLevi Alkabetz, who lived in Safed, a city in Northern Israel where the great Kabbalists of that time converged. In acrostic fashion, the poet’s name, Shlomo HaLevi, Solomon the Levite, is woven into the first letters of the poem’s first eight stanzas. It’s said that many mystics in Safed composed Sabbath poems during this period, but only “Come, My Beloved” won the deep admiration of Rabbi Isaac Luria, the father of Lurianic Kabbalah and the leading Jewish mystic of Alkabetz’s era.

Each Friday evening, as the sun set, Luria and his students would go out to the Galilean Hills to read from the Psalms and welcome in the Sabbath. Tradition has it that these excursions inspired Alkabetz to compose “Come, My Beloved.” The poem became the seventh hymn the mystics recited during their services under the open sky, corresponding to the seventh day of the Jewish week, the Sabbath. (Luria and his colleagues preceded “Come, My Beloved” with the recitation of six chapters from the Psalms, each one corresponding to one of the six days of creation.) On Friday nights, many Jewish communities across the world continue to recite this seven-hymn formula initiated in sixteenth-century Safed. And Alkabetz’s poem remains one of the few prayers composed as late as it was in Jewish history to be included in Jewish prayer books across all denominations.

Our yeshiva’s effort to usher in the Sabbath with a heightened sense of ceremony clearly dates back to Alkabetz’s time. But key phrases in Alkabetz’s poem—as well as the mystics’ practice of going out to the hills to pray—owe something to the Talmudic sages who lived more than a thousand years prior to the Jewish mystics of the 1500s. The Talmud notes that each Friday evening, two rabbis, Rebbi Hanina and Rebbi Yanai, would don elegant robes as the sun set. Rebbi Hanina would say, “Come let us go and greet the Sabbath Queen.” Rabbi Yanai would proclaim, “Enter, O bride! Enter, O bride!” (Tractate Sabbath 119:A). Alkabetz borrows from Rabbi Hanina’s pronouncement in the poem’s refrain, which also serves as the poem’s first line. And Rabbi Yanai’s words appear in “Come, My Beloved’s” final stanza. Interestingly, as they recite this final verse, contemporary worshippers turn to the back of the synagogue, to the doorway, a gesture that signifies welcoming in the Sabbath presence and recalls the practice of exiting the synagogue to pray under the sky.

In a basic reading of the poem, the first two stanzas and the final one praise the Sabbath and call upon the reader and/or G-d to welcome the day with joy and eagerness. The middle stanzas articulate a longing for the end of the long Jewish exile (which began in 70 CE with the destruction of the Second Temple). In stanza three, Alkabetz addresses this theme directly: “Sanctuary of the King, royal city . . . / For too long have you dwelt in the valley of weeping” (lines 9–10).

When I completed my studies in Jerusalem, I returned to the United States to concentrate on poetry. Of all times and places, it was as an MFA student, married and back in Pittsburgh, that I first encountered the Hasidic mystical teachings, including those that focus on Alkabetz’s poem. In particular, I found myself drawn to the Hasidic claim—based in Midrash—that all of creation, including the loftiest heavens, was constructed because G-d desires a home in this lowest realm, in our mundane world. The Jewish mystics explain that the fulfillment of each divine command, or mitzvah, draws an infinite divine light down to this physical reality, refining and uplifting the material world. According to Hasidic thought, this process will culminate in the Messianic Era, when all of physical reality has been refined and can serve as a vessel to reveal the divine unity underlying creation—a home for G-d in the lower realm. The Sabbath, when the divinity behind the world’s curtain is less concealed, is said to be a foretaste of that era.

If in Jerusalem my pendulum swung toward poetry and the secular, in graduate school for poetry, it swung toward Hasidic philosophy. I became so enchanted by this mystical tradition that I enrolled in a Hasidic yeshiva as soon as I finished my MFA. I thought I was turning my back on poetry and academia (which appeared to leave little room for Hasidic life), that I would become a rabbi and perhaps give up on poetry entirely. Ultimately, it was the Hasidic texts themselves, along with the advice of a good mentor, that helped me see things in less dichotomous terms. They helped me to realize I could attempt to live as a Hasid and, at the same time, as a poet and writing professor at a university.

Similarly, seen through a mystical lens—especially that of Hasidic mysticism—Alkabetz’s poem appears to offer a theology that contrasts with the bifurcated notion of Judaism I had encountered, and felt alienated from, in my youth. It offers a world-embracing version of Jewish life and the universe, going so far as to take a mystical form of lovemaking (which, according to Hasidic thought, serves as the source of physical intimacy between husband and wife) as its central allusion. The poem celebrates the Sabbath as a sort of restful glorification of the divine energy responsible for finitude and physicality and suggests that this energy has something to offer the divine spheres associated with G-d’s infinity and transcendence (spheres synonymous with the afterlife I had been told to strive for as an endgame). In the poem’s refrain, Alkabetz enjoins the “Beloved” to engage with the “Bride.” The mystics note that the term “Beloved” derives from “Song of Songs,” where it connotes G-d’s masculine or infinite attribute: G-d as he transcends the world. In contrast, “Bride” refers to the Shechina, or G-d’s feminine posture, that energy invested in and responsible for perpetuation of the finite and the physical.

In a Hasidic discourse on Alkabetz’s poem, likely delivered shortly before the beginning of the nineteenth century, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the Alter Rebbe, explains that, on the Sabbath, G-d’s transcendent, masculine energy, the Beloved, lowers itself to lift up the feminine finite energy, the Bride, which is invested in creation throughout the week. Alkabetz alludes to this process in the first part of the poem’s refrain: “Come, My Beloved, to greet the Bride.” The Beloved then draws the Bride—along with all of creation—back to its source in the upper spiritual worlds, representing a kind of Sabbath or respite. (The Hebrew word for Sabbath actually derives from the Hebrew term for return—in this case the Shechina returns to the upper worlds, to its source.) The “Beloved” then spiritually inseminates the “Bride” with a new divine light. As a literal translation of the refrain continues, “The faces of the Sabbath let us welcome.” The Hebrew word for faces—pnai—is rooted in the word panimiyus, which means internal or within. Here, then, Alkabetz alludes to the mystical Bride’s absorption of the mystical Beloved’s spiritual “seed,” or divine light, a kind of internal Sabbath, a restoration of energies that ultimately leads to the “birth” of another week.

In Hasidic thought, the physical world . . . is the stage on which creation’s ultimate purpose plays out. The higher worlds serve as a sort of spiritual bridge down to physical reality.

However, as noted, in Hasidic thought, the physical world—associated with Shechina—is the stage on which creation’s ultimate purpose plays out. The higher worlds serve as a sort of spiritual bridge down to physical reality. As such, according to the Alter Rebbe, Alkabetz’s phrasing implies that the transcendent, masculine light—Beloved—also experiences a kind of Sabbath, a return to, and infusion from, its source, but only once it has infused the Shechina with new life. Hence the plural wording, “The faces of the Sabbath let us welcome.” On the Sabbath, the masculine, infinite energy (along with, and for the sake of, the Bride) enjoys its revivification. It, too, is lifted back to a higher place in the heavens and receives and internalizes a new divine flow of energy. The Alter Rebbe adds that, according to Alkabetz, it appears G-d’s infinite, masculine energy and G-d’s feminine, finite mode enjoy equal footing on the Sabbath, both greeting “the faces of Sabbath”—a return to a higher spiritual realm—together. Elsewhere, the Alter Rebbe explains that, in the Messianic Era, when physicality has been fully refined and spiritualized, the two energies will share equal standing throughout the week, and in the end, G-d’s feminine attribute—which plays a more central role in making the physical world a home for G-d—will prove superior.

As a poet and as a student of Hasidic thought, it has been illuminating to take note of the overlap between contemporary poetry and the Hasidic endeavor to sanctify the quotidian. Though contemporary poetry is generally seen as a secular enterprise, the impulse to elevate the mundane, to shine light on the ordinary, also appears to drive many contemporary poets. For some, it is poetry’s central ambition. (Just look at the lines of praise on the jacket of most volumes of contemporary poetry.) Alkabetz’s poem celebrates the Sabbath, a day when the ordinary, the finite, is not overlooked or degraded but lifted up and infused with transcendent light. It would seem that—albeit in a secular sense—many contemporary poets observe a kind of Sabbath, shining luminous light on our finite lives, directing our gaze not up toward the heavens but down toward the sacred possibilities of our earthly existence.

Yehoshua November teaches at Rutgers University and Touro College. He is the author of two collections of poems: Two Worlds Exist, a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award, and God’s Optimism, which won the Main Street Rag Poetry Book Award and was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. He lives with his family in Teaneck, New Jersey.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Thank you for this wonderful , in depth analysis of L’cha Dodi. I deeply appreciate your work and your posts. May you go from strength to strength. Marilyn Mohr