Dialogue

Plague Wisdom

By Cody Hooks

When we made plans to have tea one afternoon last summer, my last in northern New Mexico, I only vaguely knew where my friend Kai lived. I knew I was to cross a mountain pass, drive deeper into the valley than the center of the village, and her house would be somewhere down a string of dirt roads. I was trying to see as many of my friends and mentors as I could before starting my graduate program here in Massachusetts.

It was the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprisings, and my visit to Kai was entangled with another of my quests: to learn from my elders—my queer elders, specifically—and gather from them some of the small and exquisite gems of our collective history. As a young queer person, I wanted to tap into the stream of energy of those who had made lives of soulful abundance out of a sometimes impossible world.

Turning off the highway and into the web of dirt roads, my thoughts were pulled back to the mundane. I was lost, in a literal way, and I had to ask a woman working in her yard where to find Kai. A few turns and then a few minutes later, I was on the couch, her cats and dogs happy to use me for a pillow, and Kai and I settled into the easy and familiar rhythm of so many of our conversations.

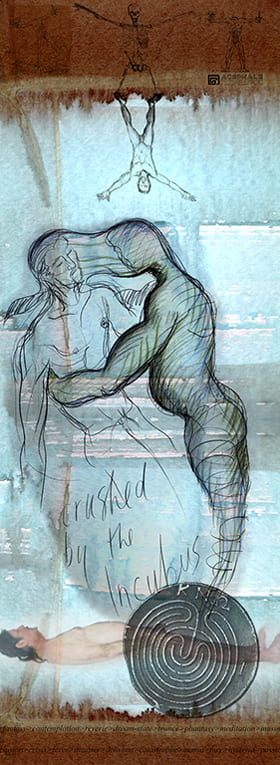

Andy Fabo, Delirious Scroll #4, digital print on watercolor paper, 96″ x 36″ (2013).

Kai had moved to the very center of gay life in San Francisco before the HIV virus took hold. But then it did. Her teacher at the Zen center asked Kai to come live and work at the first hospice in the country for AIDS patients, Maitri. The magnitude of death around her was straining, to say the least. People there faded into the last days of their lives. “I remember one day, looking at nature in the backyard with this nice Zen garden, after someone died. It was so jarring. How could we have all this beauty and have all this suffering?”1

Kai told me, “You could take a ten-minute break from the hospice to go down the street for ice cream—just to get out, to catch your breath—and someone you had just been talking to would be dead when you returned.” Another heavy blow came when her teacher died of AIDS complications the week he was set to ordain her. “Boy, I really had it laid out in front of me,” she said.

Kai was among a handful of older queer people who shared stories with me of where they had been during the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s. There were folks like Billy, a trans man who went from punk rocker to pagan priest, and Hank, a self-described S.N.A.G. (Sensitive New Age Guy) who found out he had HIV, left Los Angeles, and returned to his rural hometown and started doing HIV education in schools. Varied as they were, these stories coursed through the shadowed years and devastation of the AIDS crisis in the LGBTQ community. They bore witness to yawning death in that hellish time. AIDS was (and is) a plague of incomprehensible scale. The virus laid waste to a generation of the queer community and tested the integrity of that word—community—against the flood of needs and pain. But, from these conversations, I learned that the virus had also birthed a generation of people who gathered the wisdom—awful but precious—that came from walking their own people into death.

When I got in touch with Father Bill, through a stroke of luck he was going to be in town that weekend for a book signing. We made plans to have coffee and breakfast the morning after. I knew of Father Bill because of his residual fame in Taos, where he had been a parish priest for many years, though he was known beyond Taos. William Hart McNichols was out as a gay Catholic priest living in New York City when the AIDS crisis unfolded. His public profile from TV interviews and speaking at protests was substantial; he picked up the title of “the AIDS priest” in 1983, when he did the first Mass for people living with AIDS.2 Yet, the stories of his that stick with me most are not of his public-facing work—undoubtedly sacred though it was—but of the quieter, more intimate moments he spent near the threshold of death with other queer people—most of them young, most of them alone.

“The first person I went to visit was in bed, a man, and woman next to him . . . they were in the form of Mary holding the dead Christ. He was so weak and emaciated . . . I left thinking, ‘How could I do this? Can I witness this kind of suffering over and over again?’ It was a big question I had. I would go home and just be stunned and sit for an hour smoking in my chair, like, ‘What did I just see?’ On top of that was the prejudice and the suffering.”

Father Bill realized that he was becoming “a midwife to the second birth.” His story was the first to help me see how the AIDS crisis had called many people to become death doulas for the queer community. The call may have pulled like a vocation for some, like Bill, while for many it grew from relationships: their close friend, their lover, their ex. For others, the unvarnished need was plain to see in their own neighborhoods, as it was for my friend Kai. Most of the queer folks I talked to about the AIDS crisis were not professional caregivers, yet they showed up just the same. In their memories and stories are hard-won insights into the nature of dying in the queer community. Perhaps this plague wisdom (our current era of a pandemic has led me to think of it this way) is less about the “how-to’s” of guiding people up to the edge of death, and more about the way we walk: how we hold ourselves through it all, how we shepherd the queer community—any and all manifestations of our chosen family—into whatever unknown we face.

Hearing the stories of these knowledge keepers convinced me of this: pain and resilience is the ancestral inheritance of our queer community. I have come to see that I honor the strength and wisdom of my queer ancestors by asking for their insight as I continue my formal chaplaincy training in classes at Harvard Divinity School and in CPE programs around Boston. I am working that legacy into my practice and finding ways to give it back in the web of relationships in my queer family.

These are some of the insights I’m holding with me right now that I hope will resonate within and beyond my own community:

Show up for your community in public and private ways. For the loss of every heavyweight in the queer community, there are countless LGBTQ folks who went without a high-profile life and a long obituary in The New York Times, but nonetheless they lived a life of service to their queer family. Public-oriented work is essential, but so is the quiet work. This work will be ongoing and it will be necessary. The queer community isn’t a thing unto itself, but a humming collective of lives and struggles, love and relationships. Tending to each small piece of the web is good in and of itself, and it’s also healing for the whole.

Let it be scary. The collective experience of death, punctuated as it is by a plague (be that the AIDS crisis in its early years, or COVID-19 now), is too much to ever hold in its entirety. Each manifestation of it can feel terrifying, too. Father Bill sat in his chair stunned, Kai sat in the garden jarred. I find solace in the wisdom of letting ourselves be momentarily stilled, and irrevocably changed, by what we do.

Understand that the loss is ongoing. I can’t imagine the sense of apocalypse that queer people felt when they saw what was happening to their community. I can’t imagine how those weeks became years and those years became decades. They lost the love of one friend, then another, then another, the horrible echo of it all. Time doesn’t simply heal those traumas, and many people in the queer community are living with that trauma still. Asking to hear these stories from queer elders is no small request. If healing is to be found in gathering these stories and folding them into a more informed spiritual care for today’s queer community, it must come from a place of understanding the plague’s legacy. Be honest about the trauma, and act accordingly; at the same time, trust in human resilience and channel its power.

Find your prayers. We all have to tap into some source of energy just to get through this world, let alone to fire the great work of being in service to one another. Billy told me that after watching two dozen friends die within a year, everyone was left to “find our own prayers.” He found his way to paganism. Hank, after his experiences in LA in the 1980s (which included praying that his dying buddies would have a swift death, as this was before any treatment), found himself recharged after trips on a raft down big rivers in the West. These days, Hank told me, he gives his troubles “up to Godzilla.” Our “prayers” really are our own. For myself, I hope to draw on the legacy and energy of my queer ancestors: the living mentors, the beloved dead, and the distant forebears whose names and stories will always remain unknown to me. My prayer to them is simple—“please, guide me”—but it helps me muster a strength I wouldn’t have trying to go it alone.

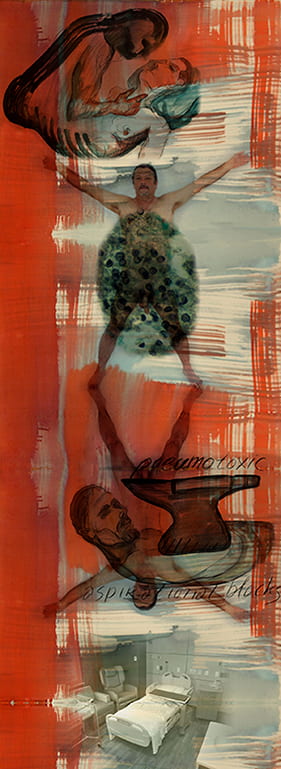

Andy Fabo, Delirious Scroll #1, digital print on watercolor paper, 96″ x 36″ (2013).

Revisit the stories. Again and again, I find myself reflecting on this handful of stories told to me by some of my queer elders. The meaning of these narratives, to my life overall and to my vocation as a caretaker in the spiritual realms, seems to unfold little by little. In order to go further into the mystery of learning from the death midwives of the AIDS crisis, I know to keep going back to those stories of the everyday moments. Those stories can become myths, and through them we can link our past struggles to the here and now and beyond. Ritualized storytelling, especially of a people’s horrors, can strengthen us by freeing up that energy and making it available for the lives of the living.

Stay with it. Or move on. Either way, no shame. Everyone in the queer community was changed by the AIDS crisis, a shift of consciousness that must have felt cosmic in scale. Some who ended up taking care of their queer siblings found themselves in a lifelong vocation. These caregivers need breaks, respites, and their own webs of support to breathe new life into those callings. But so many cycles are at work in our lives, and crises have their rhythms, too. The AIDS crisis reached a crescendo, then quieted; many people did their part, then gave themselves over to another phase of life. These folks did their small piece of the great work of holding the community through enormous, sustained loss; they took care of that one person, or did one part of work that was diffused and distributed among networks of personal relationships. There came a time, for many, when they needed to switch gears and leave the care and tending of the dying to others. That threshold of transition in a person’s life is a moment worthy of honor, not shame.

What mattered, Kai told me when she was thinking back on that time working in the hospice in the Castro, was that the LGBTQ community rose above its divisions. “We’re all here together and the way we solve this is to stay together. The kind of love you give a dying person in an epidemic like that is a motherly love. What happened to the guys . . . bodies ravished, all skin and bones, dementia, lesions all over and inside their bodies . . . to take care of someone like that, you really have to set yourself aside. What you find out is every person you take care of gives you a gift.”

The experience and understanding (and, perhaps, the capacity to be okay with not understanding) that came from the work of the death doulas of the AIDS crisis are some of the strongest, most resilient streams in the wisdom traditions of the queer community. But because these losses were so intimate and so wrenching, their stories are most often shared, if at all, in the comfort of trusting relationships. We need to enter into a gentle, loving exploration of our queer histories for the plague wisdom that blossomed and seeded itself there.

The generation of queer death midwives birthed by the slow, painful experience of the AIDS epidemic saw each other as beloved friends. True kin. Holy family. This legacy needs more than the attention it gets during Pride month. It needs the kind of loving attention possible only in real and raw and revelatory relationships between the older and the younger folks in the queer community. Let us seek out and embrace those relationships that do sustain, protect, and heal us. To learn at the feet of our queer elders, we have to let ourselves belong to one another.

Notes:

- Cody Hooks, “We’re here. We’re queer: LGBTQ People from Northern New Mexico Reflect on Their Diverse Past and Shared Future,” Taos (NM) News, July 10, 2019, A1.

- The Boy Who Found Gold, directed by Christopher Summa (Dramaticus Films, 2016). All quotes in this section are from interviews and archival footage in Summa’s film.

Cody Hooks is a queer writer, editor, and gardener with roots in the American South and Southwest. He is a second-year Master of Divinity student at Harvard Divinity School where he is focusing his studies on spiritual caregiving.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

I’ve also had conversations with Father Bill in New Mexico. I remember his Easter homily about images of resurrection, citing the spirit of AIDS patients as they faced death.

Do all the elders you spoke with now self-identify as queer? As a contemporary of theirs, I have come to accept that “queer” is being used as a brief, inclusive name for a large and diverse community, but I do not personally identify as queer.

Cody – remarkable, beautiful. You are mining a rich and important history, with vivid lessons for today. I am one of those queer elders:https://schroeder-stribling.medium.com/novel-the-echo-of-aids-in-our-days-of-coronavirus-adc7d5e824e?sk=68ab85a750fba43956fdbe992a4408cc Peace to you, Schroeder