Perspective

Nurturing Necessary Conversations

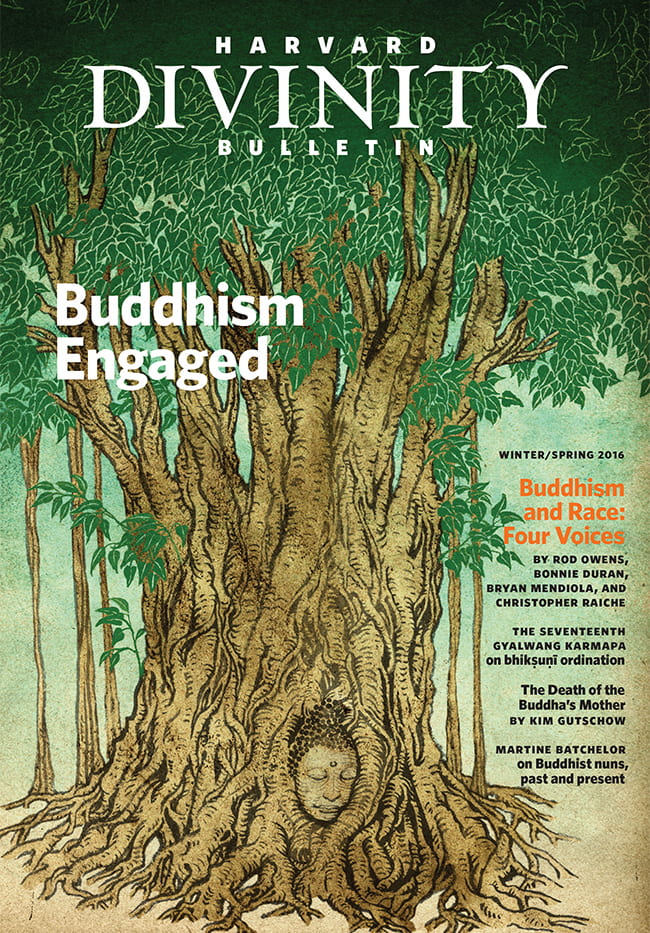

Cover illustration by Yuko Shimizu. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Julie Barker Gillette

When I first sat in meditation—perhaps ten minutes of quietly sitting in a desk chair, gazing at the abstract pattern in the industrial carpet in a college classroom—I was captivated by silence.

Magnetized by this window into the workings of my mind, I continued to meditate a little on my own. Eventually, I encountered Buddhist teachers whose freedom and authenticity challenged and inspired me to engage more fully a rich array of Buddhist trainings. Over the next decades, I devoted weeks and, eventually, several months of each year to retreat.

These longer retreats were “silent” in the sense that they did not include conversation—or even eye contact—with fellow retreatants, but they were not in truth silent. Hours of each day were spent in morning and evening liturgies. Those of us who were younger tended to be fractious and temperamental, and we struggled with these communal chanting sessions.1 Holding us to strict standards of orderly yet energetic chanting, our retreat master repeatedly exhorted us to relinquish our many opinions and petty fixations and focus on the practice and on the group.

Somewhat inscrutably, in time we became less restless and more disciplined, and we just chanted together. There were sometimes still unspoken rivalries and squabbles, and certainly each of us experienced many internal difficulties. But now everything arose in the context of an incipient yet palpable devotion to each other and our shared practice. We marked the start and end of each day in the intimacy of listening to each other, offering the power of our voices, and upholding commitments to show up as fully as we could for each other, in all our frailty and strength.

I was reminded of this as I pondered the meaning of this issue’s title, “Buddhism Engaged.” At first reading, I considered the writers as subjects drawing on Buddhist resources for their (primary) engagement with complex challenges, such as inequality, injustice, racism, sexism, and oppression. But as I read more deeply, I became even more interested in how the majority of authors are allowing themselves to be engaged—formed, transformed, reshaped—by Buddhism. I tend to agree with Rod Owens: “it is the Dharma itself that begins to work within our own minds.”

Interwoven themes of voice and expression, close relationship, conversation, and community run through this issue.

Interwoven themes of voice and expression, close relationship, conversation, and community run through this issue. Owens and AnneMarie Mal draw attention to opportunities for insight, healing, connection, and empowerment in practices of sacred song, chanting, and sound. Bryan Mendiola finds meaning in working with the pain of being silenced and unseen; this practice in part expresses itself in diversity work based on the sharing of stories that “give voice to that which feels silenced in us and allow space for others to explore and express who they are.”

Both Kim Gutschow and Christopher Raiche address the potential perils when religious discourse silences individuals, limits knowledge, and obstructs possibilities for positive change. Gutschow points out that keeping quiet about the facts surrounding maternal deaths kills women around the world. Based on textual analysis, she suggests that the death of the Buddha’s mother was not recorded because Maya was blamed for her own death, just as women in the Buddhist Himalayas continue to be blamed for their own childbirth-related deaths. Again, the antidote is giving voice, listening, and remembering: by recording maternal deaths, failures of medical care could be remedied, and the lives of mothers could be saved.

Raiche examines the tendency to silence others in our spiritual communities and exhorts us to interrogate interpretations—or misinterpretations—of Buddhist concepts that shut down conversations and silence sincere questions about how to respond to “structural dimensions of greed, aggression, and delusion.” In dialogue groups organized by Black Lives Matter, he finds a model that generates revealing, healing conversations.

Others engage with the rich, complex history of Buddhist thought and practice, revealing how Buddhism shapes cultures and lives. Erik Braun untangles the Burmese roots of the insight meditation movement and Janet Gyatso studies medical treatises from early modern Tibet with an acumen to “discern . . . other things . . . going on under the surface.”

This issue cannot be representative of Buddhism as it is practiced, studied, and taught the world over. What it does represent are some of the ways Buddhism is being engaged by Harvard Divinity School students and faculty, visiting practitioners, and other scholars.

Deepening and expanding conversations around Buddhist ministry is central to the mission of the Buddhist Ministry Initiative (BMI).2 We have invited distinguished practitioners to HDS to teach courses on Buddhism and climate change, Buddhist arts of ministry, socially engaged Buddhism, Buddhist psychology, and meditation and activism; and we have hosted many public events. We have also expanded our support for student field education and study projects in the United States and abroad.

Each year the BMI brings scholars from Asian countries to do coursework and field education focused on Buddhist ministry, thereby increasing the exchange of knowledge and insight between students trained in traditional Asian learning environments, and those who have mostly encountered Buddhism in U.S. universities and sanghas. These colloquies have been crucial, helping us to “teas[e] out multiple influences and trajectories.”3 Voices from established traditions and lineages can also act as necessary correctives. For example, Ven. Myeongbeop Sunim observes that “Buddhism in the West is more socially engaged and vocal, like a newborn baby full of energy,” but she reminds us that monastics in East Asia have been engaged in chaplaincy from Buddhism’s beginning.

As part of our mission to nurture the growth of the field of Buddhist ministry and forge lasting relationships among those who train Buddhist ministers/chaplains, we convene conferences and working groups to connect institutions and organizations engaged in such work. In these and other ways, our own community has experienced “Buddhism Engaged,” and has been changed for the better.

Notes:

- Some (including me) resorted to competitive chanting—aggressively chanting over leaders, or chanting so softly that we could not be heard.

- This is the first initiative of its kind at a divinity school within a research university. The BMI has been made possible by the generous support of the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation. To learn more, see Buddhist Ministry Initiative on the Harvard Divinity School website.

- This is how Braun describes the complex reconfigurations of Buddhism and secularism that he studies. But it also expresses the kind of insights we hope to foster in BMI courses and events.

Julie Barker Gillette (MTS ’98) is coordinator of the Buddhist Ministry Initiative at Harvard Divinity School. She has been practicing and studying Buddhism since 1992.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.