Dialogue

Listening to Silence

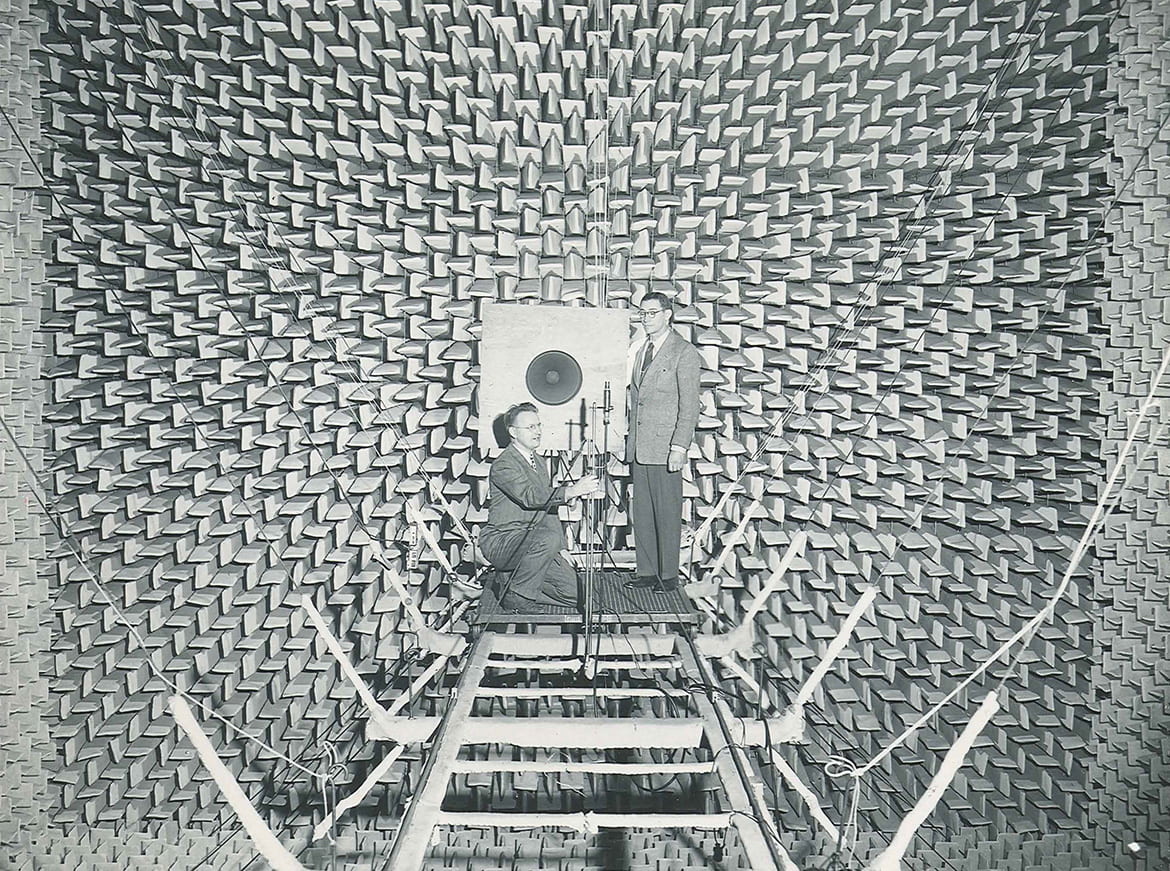

Testing a loud speaker in the anechoic chamber. UAV 605.270.1 Box 8 (SC178), Harvard University Archives.

By Jacqueline Houton

A few summers ago I went to a Quaker meeting for the first time. In the meeting house, wooden benches were arranged so that friends, as congregants are called, faced one another. There was no priest. There was no music—but maybe that’s not entirely true. I found myself thinking of John Cage’s famous composition 4'33", often described as four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence, though it isn’t silent at all. The music is what isn’t written on the score, the totality of ambient sounds in the concert hall. The absence asks you to pay attention.

On that summer day, I heard a sniffle, a siren, a sneeze. The buzz of a fly, the whir of a helicopter. A child’s voice from another room. Cicadas singing, a bench creaking. A tinny ascending scale from someone’s phone. Then another ringtone, plinking out the first nine notes of Beethoven’s Für Elise. And finally, once I closed my eyes, I heard my own breathing.

Cage wrote 4'33" after visiting the anechoic chamber at Harvard University, which stood less than a mile from the meeting house. Constructed in the 1940s by the Office of Naval Research, which hoped to test new communication systems for use in combat, the room was designed to be the quietest on the continent. Twelve-inch-thick concrete walls fended off noise from the outside world; some 20,000 fiberglass wedges covered the floor, walls, and ceiling, absorbing the sound waves within. In 1951, Cage stood in the center of the chamber on a platform suspended by steel cables. He expected silence but encountered something else.

“Anyone who knows me knows this story. I am constantly telling it,” Cage later recalled in a lecture. “In that silent room, I heard two sounds, one high and one low. Afterward I asked the engineer in charge why, if the room was so silent, I had heard two sounds. He said, ‘Describe them.’ I did. He said, ‘The high one was your nervous system in operation. The low one was your blood in circulation.’ ” The composition 4'33' debuted the following year. An early working title for the piece was “Silent Prayer.”

Quaker worship is mostly silent, a collective practice of expectant waiting occasionally punctuated by vocal ministry when a friend is moved to speak for a few words or a few minutes. That morning, as dust motes drifted through shafts of sunlight cast by plain windowpanes, an older woman’s voice eventually rose through the quiet. She spoke about the radio transmissions that had entranced her as a child, carrying faraway voices to her family’s kitchen table. She said, for her, God was a lot like radio waves—omnipresent around us, available for her to tune in to at any time, beyond the reach of our visible spectrum but no less real than light or heat. I remember feeling moved, and a little envious of her calm conviction. I wondered if I had always been tuned to the wrong frequency.

Cage composed several works featuring radios, including 1951’s Imaginary Landscape no. 4. It calls for 12 radios and 12 pairs of performers—one to control the tuning, the other to adjust volume and timbre—plus a conductor unafraid of cacophony. The score provides indications for durations and dynamics, but the sonic material is left to chance, assembled from whatever snatches of songs, advertisements, news reports, white noise, and silences are surfing the airwaves at that moment. It strikes me as a pretty good metaphor for a congregation—all those busy brains in one room, inevitably bringing their own noise, their own static.

The pandemic has forced congregations of all kinds to find other forms of fellowship as friends have cared for one another by staying apart. Last year, I joined a dozen neighbors I’d never met on Zoom to train as a volunteer for a helpline operated by a nearby nonprofit. Every Tuesday, I would sit at my kitchen table and wait for my cell phone to ring. Some people called for resource referrals, looking for shelter for the night, a hot meal, a food pantry, a job, a support group, legal aid, or help navigating labyrinthine health-care and housing bureaucracies. Others called because they needed someone to listen. They talked about trauma, about family troubles, about health setbacks, about loneliness. During the training, the center’s director coached us on how to paraphrase, to summarize, to validate, to ask open-ended questions. But she also emphasized the importance of silence and asked us to resist the natural impulse to fill it. Silence can give a caller space to think, time to sit with a feeling, permission to say more.

During some shifts, calls came rapid-fire. Other shifts, there were no calls at all. A cell phone is a two-way radio. It converts our voices into electrical signals, then into radio waves, which travel through air at the speed of light. These are relayed by cell towers, turned back into electrical signals, then into sound. The process is nearly instantaneous. For most of human history, this might have been mistaken for a miracle.

I recently read that the engineer at Harvard was mistaken, that John Cage couldn’t possibly have heard the whistling of his nerves. He might have been hearing something else, or his brain may have invented the sound to fill the void. Does it matter? He believed in what he heard, and that belief affected his life and work for the better.

As an agnostic who prays, I do not know if God is nonexistent or silent or simply quiet. But I am trying to remember that silence can be a form of care. I am trying to be receptive to the possibility, however remote, that someone is listening.

Jacqueline Houton is a copyeditor of kids and YA books and a senior editor at Boston Art Review. A former editor of The Improper Bostonian, she has written articles and essays for Big Red & Shiny, Bitch magazine, Boston magazine, HerStry, Pangyrus, Publishers Weekly, and other publications.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Beautiful article!