Perspective

Knowing and Unknowing

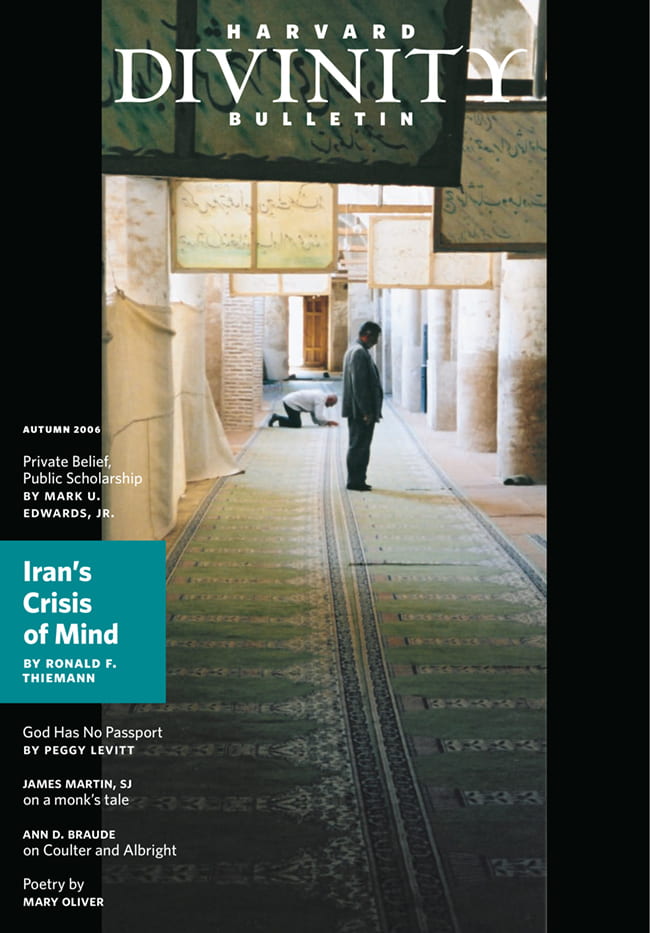

Cover photo of a mosque outside Yaz, Iran, by Kira Brunner Don. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Will Joyner

In introducing his recent PBS series Faith and Reason, Bill Moyers makes this figurative leap: “Throughout the double helix of our DNA, it seems, the molecules of faith and reason chatter away, and it’s in our interest, and the world’s, that they stay on good speaking terms.” At first I thought Moyers was straining a bit, but the more I considered his metaphor the more I appreciated his skill in loading into one rather humorous sentence the private as well as the public aspects of a situation that’s dire, both nationally and globally.

Even before we watched this commendable television project, which I write about in more detail on page 107 (“Riding the Seesaw of Faith and Reason”), we here at the Bulletin knew that the sparks between faith and reason were to be at the core of this issue of the magazine. In one sense, they’re at the core of every edition we produce, but in the particular lineup of articles you’ll find here, there are explicit attempts to judge how religious belief might, or might not, threaten scholarship and teaching at “secular” American universities; how religious belief and the professional pursuit of truth within an academic field might, or might not, exist dynamically for a scholar in a country dominated by one version of one faith; and how the religious beliefs of the creators of one important scientific theory might have been misconstrued historically.

We should all regularly ponder what we don’t know, and not turn away from it.

Any of these three featured articles—by Mark U. Edwards, Jr.; Ronald F. Thiemann; and John Hedley Brooke, respectively—could have “carried” the cover in expressing our focus on, and concern about, the gaps and bridges between faith and reason. We finally chose perhaps the riskiest course—to emphasize Thiemann’s report from Iran—because, first, it represents such a rare opportunity for an American scholar (and for an American publication), and, second, we, like the rest of the world, watched this summer as a possible showdown between the United States and Iran reared up beyond the tragic events that unfolded in Lebanon and Israel. We, like the rest of the world, couldn’t avoid the enormity of this looming crisis.

By the time this magazine has been printed, the circumstances of Iran’s stance toward United Nations expectations will certainly have changed in some manner. Perhaps a new calm will have prevailed, and the world will have been able to relax somewhat. But the circumstances of the Iranian scholars who opened their hearts to an American visitor will almost certainly not have improved. Their faith/reason identity, which, given Iran’s rich cultural and intellectual past, should be a source of pride and accomplishment, will continue to be a wrenching dilemma.

In that light, I would suggest that this rare report from Iran’s academic venues enhances, rather than overshadows, the other two articles mentioned above.

As Edwards says in “Private Belief, Public Scholarship,” his article on how mainstream American academia is handling the presence of personal religious belief amid teaching and collegial relationships: “The best way to come to grips with the appropriateness of, and limits on, the expression of belief in scholarship and teaching is to take time to talk. . . . I recommend conversation, because a proper conversation aims at communicating and understanding, not (or at least not necessarily) at agreement or resolution.”

And as Brooke says in “Darwin and God: Then and Now,” his article on the skewed history embedded in the “intelligent design” debate: “What inspiration might religious thinkers find in the real, as distinct from the caricatured, Darwin? We might all learn something from Darwin’s humility. In matters concerning discourse about God there were, for him, no simple answers. On ultimate questions about intentionality and purpose in evolutionary processes, he preferred humility to arrogance, saving his severest censure for those who believed they could reason from nature to God.”

American scholars, compared with Iranian scholars, enjoy much greater freedom in approaching questions of faith and reason, and in knocking down barriers that hinder discussion of those questions. They also enjoy much greater latitude in ensuring protections for the rights of all religious and ethnic groups. I urge all our readers—whether they work in academia or not—to take up the challenge implicit in Edwards’s article: don’t be afraid to speak up, in appropriate fashion, about how personal faith affects your work and workplaces, and your participation in the other public places of America’s democracy.

Likewise, all of us who feel we “know” a certain field—any field, whether scientific or not—should, it seems to me, regularly ponder what we don’t know, admit what we don’t know, and not turn away from what we don’t know. The issues that involve religious faith and science in 2006—stem-cell research, abortion rights, evolutionary theory, global warming, to name just the most obvious—are so myriad and wide-ranging that we are all implicated. Perhaps the chance for more civil discussion of these topics lies in our willingness to mark out our own areas of knowing and “unknowing,” to pay attention to one another’s areas of knowing and unknowing, and to proceed humbly together.

To go back to Bill Moyers’s metaphor: Those molecules of faith and reason are chattering away all the time as a kind of cultural spectacle—on our television screens, in books and newspapers, in pulpits, in innumerable blogs across the Internet, through the headphones connected to our iPods. But they are also—just as importantly—chattering away inside my mind and yours, or inside my soul and yours. It truly is in the world’s interest that we bring coherence to that internal chatter, and, as individuals, contribute what we can toward a better harmony.

Will Joyner is editor of the Bulletin.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.