In Review

Jewish Creators, Resonant Themes: Comics as Midrash

The superhero comic book and the graphic novel were both Jewish inventions.

By Hillary Chute and Emmy Waldman

If you don’t know much about comics—despite the Bulletin’s 2009 feature on the comic book series Watchmen1—you are still likely to know a little bit about superheroes, costumed crime-fighting figures like Superman and Batman who have become American cultural touchstones. If you’ve heard anything about “graphic novels”—the ambitious, long-form comics stories that exist between book covers—or noticed graphic novel sections in your local bookstore, you probably know of Art Spiegelman’s Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, the world’s most famous example of literary comics. The two most salient developments in comics history—the rise of the superhero comic book in the 1930s and the rise of the graphic novel in the 1980s, both of which profoundly shaped cultures of expression—were Jewish inventions.

Yes, Superman—the world’s inaugural superhero—was created by two bespectacled Jewish teenagers from Cleveland: Jerry Siegel, who wrote him, and Joe Shuster, who drew him. The friends met when they were both age 16 at Glenville High School. The first incarnation of the Superman character appeared in their own self-published magazine, titled Science Fiction, which they created together during their school years. Siegel, an avid science fiction fan who worked at the school paper, was the youngest of six children born in Cleveland to Jewish Lithuanian immigrants (his father’s given name was Segalovich); Shuster had come to Cleveland from Toronto with his own Jewish immigrant family (his father, born Shusterowich, was from the Netherlands, and his mother was from Ukraine). In 1932, Siegel’s father died on the job—the exact cause of death still remains unknown—when his secondhand clothing store in Cleveland was robbed at gunpoint. In the wake of the tragedy, the two teenagers experimented with different story lines involving superhuman power and ultimately settled on the do-gooder character we know today: a flying crimestopper who is invulnerable—even to bullets. The pair revolutionized comics in 1938 when Superman, donning a blue bodysuit and red cape, graced the cover of Action Comics #1, lifting a car above his head. Superman was instantly popular, selling out the print run of Action Comics, and quickly creating a booming field of superheroes in his wake.

Not only were the two most important developments in comics history Jewish inventions, but both religious and cultural strains of Judaism find privileged space for expression in this literary genre.

So much about the Superman character, in addition to his billed role as a “champion of the oppressed,” resonates with the exilic Jewish experience: born Kal-El, Superman’s father puts him in a spaceship and ejects him from their home planet, Krypton, right before the latter’s complete destruction. Kal-El lands in the Midwest in what is probably Kansas, where he is adopted by a kindly farming family and dons the guise of Clark Kent. He is a literal alien who not only champions the oppressed but has a dual identity: one connected to his home culture and the other stitched to a culture which he strives to improve even as he struggles to pass within it. He needs to “pass” on two levels, leaving behind both Kal-El and Superman to function in American daily life by inhabiting an alter ego. The one thing he isn’t invulnerable to is home. In a symbolic twist, any material from his home planet, called Kryptonite, can leech away his powers. The affinity between Superman and Jewishness, or Jewish forms of cultural experience, emerges here in the dangerous pull exerted by the places once called home, which can return like repressed memories to sharpen the pain of exile and homelessness. As Jules Feiffer, the legendary cartoonist, playwright, and screenwriter, quipped in The New York Times Magazine: “It wasn’t Krypton that Superman came from; it was the planet Minsk or Lodz or Vilna or Warsaw.”2 There is even a book titled Superman Is Jewish? How Comic Book Superheroes Came to Serve Truth, Justice, and the Jewish-American Way. What’s important here is how a typology, a mythology, that has shaped the twentieth- and twenty-first-century American popular imagination so profoundly was a Jewish invention, not only by virtue of its Jewish creators but also by virtue of the resonant themes of its story—themes raised, of course, to the scale of the intergalactic.

Many, many Jewish creators of still wildly popular superheroes followed, including Bob Kane aka Robert Kahn and Bill Finger (the pair who created the orphaned, brooding Batman); Jack Kirby aka Jacob Kurtzberg and Joe Simon (the co-creators of Captain America, whose first appearance on a comic book cover in 1941 shows him punching Hitler); and one of the most celebrated figures in comics history, Stan Lee aka Stanley Leiber (the co-creator of Spider-Man, the Hulk, the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, and many others from Marvel Comics). Even before the superhero craze, Jewish cartoonists had made their mark: there was Al Capp aka Alfred Caplin, whose syndicated newspaper strip Li’l Abner, debuting in 1934, became the first widely read comic based in the American South (it gained 60 million readers), and Milt Gross, whose satirical 1930 “wordless novel” He Done Her Wrong deployed Yiddish-inflected dialogue throughout.

Jewish creators reinvented the medium of comics again and again, creating new idioms and formats that transformed American culture’s sense of the possible for comics. Will Eisner not only drew an early superhero, The Spirit (“his nose may have turned up, but we all knew he was Jewish,” Feiffer deadpanned of the character), but he also was the first cartoonist to publicly describe his work as a “graphic novel”—words that appeared, momentously, on the cover of his 1978 book A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories: A Graphic Novel, a series of four linked vignettes about immigrants in a Bronx tenement in the 1930s. The first official graphic novel is about Judaism; in the opening story, Frimme Hersh loses his faith in God after the sudden death of his daughter Rachele. Jules Feiffer, who started working as Eisner’s assistant as a teenager, essentially created the very idea of intellectual comics mid-century with his collection of strips diagnosing the neuroses of society, Sick Sick Sick; he became a staff cartoonist at the Village Voice, a frequent contributor overseas to the London Observer, and a trail-blazing cartoonist-intellectual of the Paris Review set, carving a space for deep sociological satire within comics. Also mid-century, cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman invented the mode of self-reflexive humor that now is our dominant idiom—what we simply call humor. Kurtzman’s keenly intelligent, parodic MAD magazine offered a send-up of everything America valued in a sophisticated visual language that played off of media aesthetics and its own awareness of comics as a visual form. It presented comics as a form of sharp critique against consensus culture and a giddy form of entertainment at the same time.

But perhaps the most important contemporary figure in the Judaism and comics landscape is Art Spiegelman, born in 1948 to two Polish-Jewish Holocaust survivors. Harvey Kurtzman’s MAD was religion for young Spiegelman. One of Spiegelman’s autobiographical strips has the irreverent, tongue-in-cheek punchline: “I studied MAD the way some kids studied the Talmud.” Maus, which appeared in two volumes in 1986 and 1991, pictures Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. It is driven by the testimony of Spiegelman’s father, Vladek, and shuttles back and forth between 1940s Poland, where Vladek and his wife Anja struggle through the war, and 1980s New York City, where cartoonist Spiegelman interviews his father and struggles to visualize the past. Beyond the fact that Spiegelman is a Jew, beyond the fact that his magnum opus tells the story of his own parents’ Holocaust survival, Maus demonstrates what a Jewish comics text might look like when it confronts, head-on and with insistent self-reflexivity, the representation of the Holocaust and its aftershocks.

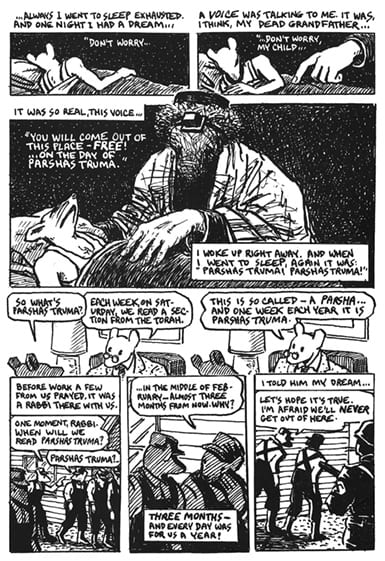

First, Maus is striking for the respect it allows Judaism, despite Spiegelman’s professed ambivalence and skepticism about Jewish faith. Several mystical moments, elaborated in imaginative graphic detail, punctuate the text. Maus catches and frames the shimmer of these numinous events in Vladek’s testimony. For instance, while a prisoner-of-war at a labor camp near Nuremberg in 1939, Spiegelman’s father, Vladek, has a dream, which Spiegelman draws with patient care. “A voice was talking to me,” Vladek remembers: “It was, I think, my dead grandfather . . . It was so real, this voice.” “Don’t worry, my child . . . ” it says. These words, written in white, hover eerily in the darkness; without a speech balloon to indicate a speaker, the writing takes on an otherworldly dimension. “You will come out of this place—free! . . . on the day of Parshas Truma.” One Saturday each year, this particular portion of the Torah, called a parsha, is read aloud in the Jewish liturgy. At the top of the page, we see young Vladek tossing and turning in his sleep against a night sky stippled with distant stars. An enormous hand, cropped above the wrist, reaches out with one bent finger to tap his blanket—redolent of the hand that appears and writes on the wall in the story of Belshazzar’s feast in the biblical book of Daniel.

Art Spiegelman, Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale. My Father Bleeds History (Pantheon, 1986), 57. Courtesy Art Spiegelman

The cartoonist observes this mystical moment—and focuses attention on it—by altering his drawing style, exchanging the simplified black contours he uses throughout the text for realistic rendering. Vladek’s dead grandfather looms large in the center of the page, his whiskered face, withdrawn, in shadow; he wears a prayer shawl, tefillin, and a traditional hat, and he lays his massive hand over the exhausted dreamer. In comics, each panel usually represents a unified moment in time. The dream mouse, his massive form too big for the panel that enframes him, seems to come to Vladek, and to us, from beyond: beyond time, beyond life and death, beyond the very order of the narrative and its animals-as-humans conceit.

What turns Vladek’s Parshas Truma dream into an article of faith in Maus, however, is the fact that it comes true. Back in the labor camp, three months pass. Vladek loses all sense of time; he also forgets about the prophecy of the dream. One Saturday, Nazi soldiers line up all the prisoners, give them release papers, and load them onto a train to Poland. Vladek’s friend, a rabbi, whispers that it is the day of Parshas Truma. “This is for me a very important date,” Vladek states. We see father and son sitting facing each other in their New York home; Artie, as his father calls him, is asking follow-up questions, per usual. Jewish history is indeed supposed to be taught this way, according to rabbinic tradition. (It is no accident that the Passover narrative, the story of the exodus, must begin with, and respond to, questions asked by a child.)

“I checked later on a calendar. It was this parsha on the week I got married to Anja . . . And this was the parsha in 1948, after the war, on the week you were born! . . . And so it came out to be this parsha you sang on the Saturday of your bar mitzvah!” Vladek explains. The day of Parshas Truma—usually falling somewhere between February and March—thus takes on special, superstitious significance, because it marks the anniversary of key milestones in Maus. Vladek and Anja’s wedding, Vladek’s liberation (short-lived though it was, with Auschwitz soon to come), Art’s birth and then bar mitzvah: these represent the stations of a long, wandering journey of transgenerational survival.

In Parshas Truma (“gift” in Hebrew), God instructs the Israelites on how to build the mishkan, or “portable sanctuary”—ornately constructed out of gold, wood, and gemstones—for the Tablets of Testimony, which they carried with them into the wilderness. Maus offers itself as an update of Parshas Truma: “With comics, you’re cobbling together little things and carefully placing them. It would be like . . . making a 100-faceted wooden jewel box. It’s highly crafted work,”3 Spiegelman has confirmed. Maus is the gift of a highly crafted structure within which to carry a historical narrative from the depths of the past to the present.

If the content of Maus is Jewish—which is to say, about Jewish people and history—so, too, we can recognize that its process of construction participates in a long Jewish cultural tradition. Midrash, a rabbinical tradition of biblical interpretation dating back to ancient times, encourages questioning and debate, along with imaginative expansion. The Hebrew root of the word midrash means “to seek out, inquire, demand.” David Stern—who invited Spiegelman to Harvard in 2017—explains that midrash is found “at the point [where] exegesis turns into literature.”4Maus also exists at that point, between a text and its interpreter. In Spiegelman’s methodology—his inquiring, sometimes demanding inquest of his father, and his self-conscious probing of his own responses, which together shape the unfolding story—we note the sustained and imaginative analysis, skepticism, and debate characteristic of Talmudic inquiry. Maus becomes a nimble comics midrash that seeks to make sense—through constant and repeated verbal questioning and rigorous textual attention—of an inherited historical tale.

In comics, both religious and cultural strains of Judaism find privileged space for expression. The connection has sparked its own academic debate—there are even essays such as “Is Midrash Comics?” and “The Secret, Untold Relationship between Biblical Midrash and Comic Book Retcon.” And at the same time, the comics field has welcomed many new titles, from JT Waldman’s Megillat Esther, an adaptation of the Book of Esther, to Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s Love That Bunch, a chronicle of growing up in postwar Jewish Long Island, and controversial Jewish works such as Eli Valley’s Diaspora Boy: Comics on Crisis in America and Israel. In an interview, comics theorist Scott McCloud defined the form as “secret labor in the aesthetic diaspora” because so much of the creative work goes on behind the scenes, at the artist’s drawing table. If this clever phrase feels like a metaphor for Jewish experience, it also captures the deep historical roots of comics.

Notes:

- Jonathan Schofer, “Ethics and Vulnerability in Watchmen,” Harvard Divinity Bulletin 37, no. 2 & 3 (Spring/Summer 2009): 64–69.

- Jules Feiffer, “The Minsk Theory of Krypton,” The New York Times Magazine, December 29, 1996.

- Art Spiegelman, “Art Spiegelman,” in Dangerous Drawings: Interviews with Comix and Graphix Artists, ed. Andrea Juno (Juno Books, 1997), 12.

- David Stern, “Midrash and the Language of Exegesis: A Study of Vayikra Rabbah, Chapter I,” in Midrash and Literature, ed. Geoffrey H. Hartman and Sanford Budick (Yale University Press, 1986), 105.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.