Repose

‘It Felt Like a Community Was On My Wall’

A Q&A with Artist Ellen Elmes

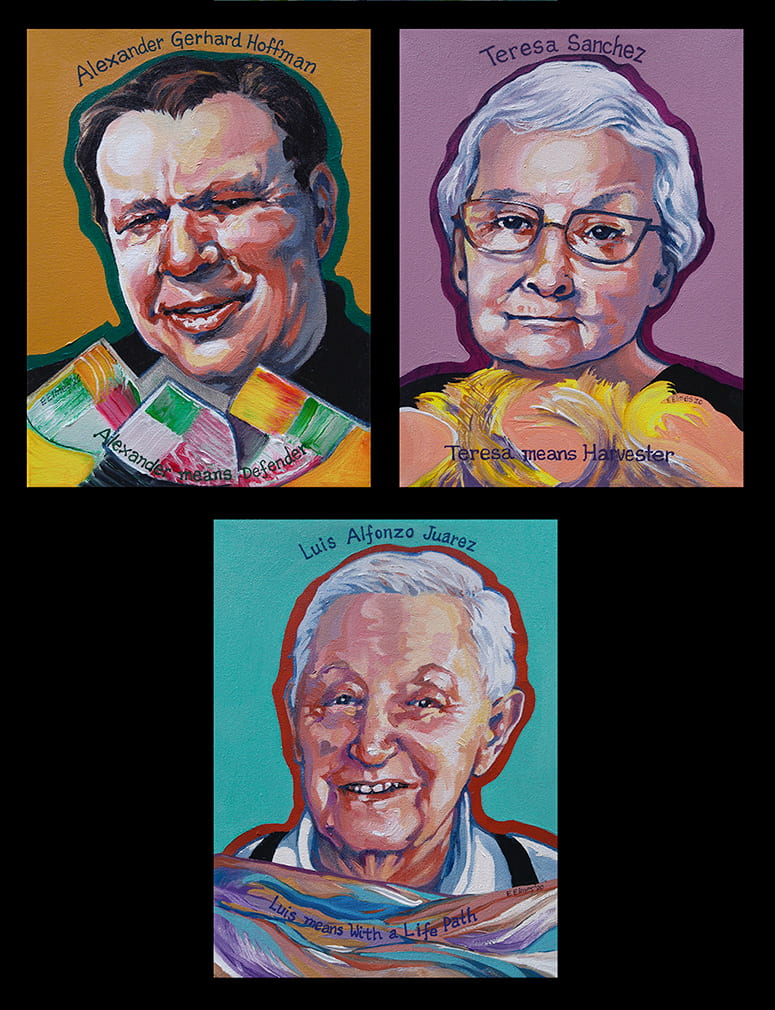

Artist Ellen Elmes didn’t know any of the 23 victims of the August 3, 2019, mass shooting in El Paso, Texas, but after she read Harvard Divinity School Professor Davíd Carrasco’s “Saying the Mexican Names” tribute on the first anniversary of the tragedy, she felt moved to learn more about them. As she researched each person, they became real to her. She found herself compelled to express her sorrow by painting individual portraits of these mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, grandparents, sisters, brothers, and friends who came from both sides of the Mexico/U.S. border. Wendy McDowell, editor in chief of the Bulletin, spoke to Ellen about the project.

Bulletin: Artists often talk about inspiration. What inspired this project to paint the portraits of the 23 victims of the El Paso shooting?

Ellen Elmes: When I read Davíd Carrasco’s “Saying the Mexican Names,” I was struck by his personal experience with his father, how his father had to give him “the talk” because of racism against Latinos, and his feeling fearful and threatened in a public place. It was shocking to me. And when he went on to talk about his visit to El Paso and to the “Grand Candela” monument, I realized it had been just a year since the murders of the 23 people there.

It dawned on me that this horrible incident of racism and gun violence had left my memory in only a year’s time. Reading Davíd’s essay on the one-year anniversary and his emphasis on needing to know the names of the people killed, I thought that maybe I could more deeply understand and remember the humanity of real, individual lives suddenly ended by violence if I painted their portraits.

So I started looking up the names and pictures of the 23 people who were murdered. Their stories caught me. Once I started to do the first painting, I knew I was going to keep going and do them all.

Courtesy Ellen Elmes

Bulletin: How long did you work on the portraits and what was it like to paint them?

Elmes: In October 2020, I painted one portrait each day through all of October. Every time I started painting a portrait, it was like I was in this new world. It’s hard to explain, but by painting a person’s face and making decisions about colors and expressions and trying to bring to a two-dimensional surface a person’s life, which is three-dimensional, you get completely immersed.

It’s like coming to know people as real, vital human beings. After I painted each portrait, I felt like I’d known this person and I’d almost forget that they were dead.

Bulletin: What did you learn about these human beings whose faces you painted?

Elmes: Their stories are all remarkable, and so many of their stories include ironies and coincidences. It also struck me how many of them had gone to the store to buy things for others. One woman, Maria, was on her way to pick up her daughter at the airport after a trip to Europe, and she was so excited to see her and find out about it. Gloria Marquez had been trying for over 13 years to help her daughter get a visa to come to the US from Mexico. A week after she was killed, her daughter finally got the visa but had to use it to come into the states and go to her mother’s funeral.

The oldest person, Luis Juarez, was 90; the youngest, Javier Rodriguez, was 15, with ages all in between. There was the whole spectrum of living a life from the young, to people coming into their middle years, to those growing old. There were couples, a young couple in their 20s, Andre and Jordan Anchondo, and other couples, Sarito Regalado and Adolfo Henandez and Raul and Maria Flores, who had celebrated decades of anniversaries. Couples with many children and grandchildren. There are so many people that are affected by the death of each person.

Some of the people killed deliberately stood in front of their children, grandchildren, and wives to keep them from getting killed.

There was a group outside of the Walmart that day of children, parents, and grandparents selling food to raise money for a girls’ soccer team. One of the girls’ beloved coaches, Guillermo Garcia, died nine months after the shooting, after many surgeries. Here was a girls’ soccer team that the town was very proud of, and everyone on that team has been deeply impacted.

Courtesy Ellen Elmes

Bulletin: Was this a different kind of project for you? What other kinds of work have you done?

Elmes: I rarely do portraits, normally I’m a muralist and a watercolor painter. I’ve been painting for 50 years and doing murals since 1980. From early on in my career, I’ve tended to avoid being a portrait artist. When people would ask me to do portraits of their family members, I always felt like I didn’t want to take on that responsibility because they might not see the person the way I saw them.

I do have to include some portraits in murals but only because I need to depict the important famous people in them. For example, before the COVID shutdown I was in conversation with people in Johnson City, Tennessee, about doing a mural for them in celebration of the centennial of the 19th Amendment. Tennessee was the 36th state to ratify so they asked me to do a mural about the suffragists from Johnson City who were very active from 1916 to 1918. From the spring into the summer, I focused on painting these panels on fabric, which then get put together and adhered to outdoor walls. I was able to complete it and my husband helped me install it in September 2020. I’d read David’s piece in August, so I was freed up to take on something new in the fall.

As it turned out, the year of COVID was an extremely reflective time for me as an artist. Being at home all the time gave me a much broader and deeper opportunity to reflect first before I painted something. I also think this has to do with my age. I’m in my mid-70s, and I see things in retrospect. The unexpected events of that year, not just the virus but all the political upheaval the virus brought on, was a very deep time that led me to ponder many things as an artist.

I’ve never done portraits like these before, with the use of bright colors and a bolder style for their faces. So not only was it very meaningful to learn about the people and their lives but it was an artistic challenge as well.

I don’t think I could have done this project in another year, because I probably wouldn’t have had the time to focus my attention fully on it since I’d be involved with multiple mural projects and other commitments. I’m so thankful I had the time and presence of mind in 2020 to do this personally meaningful project.

Courtesy Ellen Elmes

Bulletin: You ended up reflecting on the name of each person who was tragically killed in El Paso, and some of the mythological and cultural meanings their names held. What led you in this direction?

Elmes: Again I’ll give credit to Davíd Carrasco and his emphasis on saying the names and remembering the people who died by name. That started something in my head where I asked myself: How can I emphasize their names?

I’d never done anything like this before, either, in which I’ve included a focus on the names. I started looking up their first names and was able to find different connections. Some were more mythological, going back to earlier times, while others were more fanciful around the meaning of the name.

For instance, I discovered the name Raul means “Wolf Counsel” so I included a wolf in the border of Raul Flores’ portrait. Raul and his wife Maria were both killed in the shooting, and those who knew them remarked on how loving, humble, and giving they were. They had been married for 60 years, and had three children, 11 grandchildren, and 12 greatgrandchildren. I imagined when doing Raul’s portrait that his counsel to his children and grandchildren over the years will be long remembered and treasured.

In some cases there were several choices for meanings of the name, so I tried to decide which one reflected best what I’d learned about the person.

I always wondered what the families would think when they saw what I attached to the person they loved. It may not have clicked for them. It felt a little presumptuous on my part, do you know what I mean? I just had to hope that it would ring true with the families when they got the portraits.

I tried to make the images as true as possible, too, but I was only working from photographs. I always tried to capture the spirit of their faces. For example, the oldest man—Luis Juarez—had what appeared to be a birthmark on his cheek in the photo. From when I first noticed it, it looked heart-shaped to me, so in the painting I deliberately made it be a heart shape on his cheek.

Courtesy Ellen Elmes

Bulletin: Where are the portraits now?

Elmes: From the beginning, I knew that I wanted to send them to the families, but as I was painting them, I also knew that I wanted to “do it the right way.” I didn’t want to be asking for addresses of families who didn’t know me, which might make them wonder, “What’s she trying to get?”

I waited until they were all done before I contacted Davíd Carrasco. I didn’t realize that he still had so many associations and connections with people in El Paso, and right away he was able to involve local leaders who have been supporting those families all along. We had a couple of Zoom meetings and I was so impressed by the leaders in El Paso and their sense of caring. They spoke about all the different emotions families were still dealing with—grief, anger, bitterness. It was obvious that they haven’t moved on and that they want to keep the event in people’s minds and hearts and memories.

Hearing them talk about people in their community with such compassion impressed me. It was like a miracle, but between Davíd Carrasco, Charlene Higbe (Coordinator of the Moses Mesoamerican Archive at Harvard), and leaders like District Attorney Jaime Esparza, we were able to find a family member to send each painting to. We did two separate mailings, but apparently all the paintings got there the day before Christmas last year. That was pretty neat!

Only one painting came back because of a change of address, but I was able to get back in touch with the son and get it to him. With the virus lockdown, people were no longer allowed to come into El Paso from Juarez as they’ve always done, but I found out that many people maintain post office boxes in El Paso. It’s been more difficult, but El Paso and Juarez are still intimately connected.

Courtesy Ellen Elmes

Bulletin: Did painting these portraits teach or show you anything that was new or unexpected?

Elmes: The unexpected part of it was that I became so deeply engrossed in their individual life stories, and each morning I’d get up and think, “I get to paint another person today.” I’ve described it as a daily mantra. It was a delight to get to know each person.

As I finished each portrait, I had a board up on the wall where I would tack it up. Faces started lining up on this board day after day, and it was like seeing all of these people I felt like I now knew. On some days, I would be overwhelmed by a feeling of profound sorrow that these smiling bright faces were all gone, all murdered.

By the time I was done, there were three solid rows of people, and I realized all the connections between people. Husbands and wives, people with connections throughout the city and across the border. It felt like a community was on my wall. I miss them not being there.

Bulletin: I know you’ve continued to be involved in events to commemorate and remember this community you’ve gotten to know through your paintings. Can you describe how the portraits were part of events in El Paso in August 2021?

Elmes: My husband Don and I had the privilege of driving to El Paso for a four-day involvement in community gatherings and events this past August to commemorate and remember the 23 people killed in the Walmart massacre two years before. Community leaders graciously facilitated the showing, on three different occasions, of reproductions of all 23 portraits I had painted, including a final showing at the Healing Garden Dedication Ceremony on August 3.

Don had created a portable display unit for exhibiting the portraits, which we did the first time for an El Paso public reception following the premier of Song for Cesar, a film by Abel Sanchez and Andres Alegria. Don and I had set up the display earlier in the afternoon with the help of servers and housekeepers who were preparing for the reception. When we came back for the reception that evening, we found that the women had laid clusters of beautiful fresh flowers in front of the portraits. We were very touched by that.

That night, and during a luncheon the following day, Don and I, with the assistance of Pedro Morales, one of Davíd’s Harvard teaching assistants who grew up in Juarez and El Paso, had the chance to meet face-to-face many people who dealt with the tragedy of the shootings from day one—County Judge Ricardo Samaniego, a driven, socially-dedicated man; Jaime Esparza, former El Paso County District Attorney and a compassionate advocate for the victims’ families, and his gracious wife Noelia Molina; and Chris Tirres, a DePaul University Professor of Religion, former student of David’s, and native of El Paso, who gave an impassioned speech of thanks to El Pasoans and delivered a pledge on behalf of Davíd and HDS of ongoing support for the community. Many local participants made a point of thanking us for creating and bringing the portraits to El Paso. I kept feeling overwhelmed with emotion.

We were also treated to a mural tour in the Segundo Barrio with Jesus Cimi Alvarado, a celebrated Chicano artist whose murals are all over El Paso and who works with young, emerging artists to encourage and enable creative opportunities for them. And on the last morning of our visit, our group was moved by a presentation by Manuela Gomez, a Mexican native and an El Paso Community College philosophy teacher dedicated to working for justice as a journalist, teacher, and with her students in various volunteer projects.

Opening night of the Healing Garden. Photo by Ryan Christopher Jones

Bulletin: I know that the core event bringing you to El Paso was that dedication ceremony and lighting of the Healing Garden in Ascarate Park on August 3. What do you remember from that event?

Elmes: It was a beautiful evening gathering of surviving family members, massacre survivors, city and state leaders, Mexican national and consulate officials, clergy, and creators of music, film and activism. We have so many treasured memories of the ceremony, but these are a few we will never forget:

- The serene, plaintive notes of Zuill Bailey’s cello wafting into the evening sky.

- The rousing national anthems of both the US and Mexico sung by those onstage and offstage.

- The charge and hope by County Judge Samaniego: “May this Healing Garden help us be the light that we need to make a profound difference in our community.”

- The matching T-shirts of large family groups in the audience celebrating the lives of their beloved lost kin.

- The resonance of the gong notes after each name of a life taken by racism was read.

- The launch of silver balloons into the gentle wind by children and grandchildren of Juan de Dios Velasquez after his name was read.

- The passion and call to action by Dolores Huerta at 91 years of age.

- The conflicting yet equally deep feelings of loss and hope throughout the ceremony.

The ultimately meaningful experience of the night, of course, came when everyone regathered along the arced wall of the Healing Garden, where each person’s life was commemorated with a beautiful plaque. All along the wall, in small clusters and in front of each plaque, stood the husbands, wives, children, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, grandparents, uncles, and aunts of those who had been killed.

During that last hour of the gathering, Don and I were able to see the faces, and to hug, shake hands, and cry with many of those to whom we had sent my portraits of their loved ones. Every person we met was kind and so appreciative, and so proud to have their beloved kin forever remembered on the wall. What a privilege it was to be there, to witness such dignity and courage to move forward as a community.

Ellen Elmes

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

awesome work.

What beautiful portraits of the victims of a young man from North Dallas who drove to El Paso to murder people he didn’t even know. Ellen’s skill along with Dr. David Carrasco rescued them back to our memory. This is a constructive respond to the fact that the names were not even mentioned in the initial memorial in the Walmart parking lot.