In Review

Into the Infinite Together

By Stephanie Paulsell

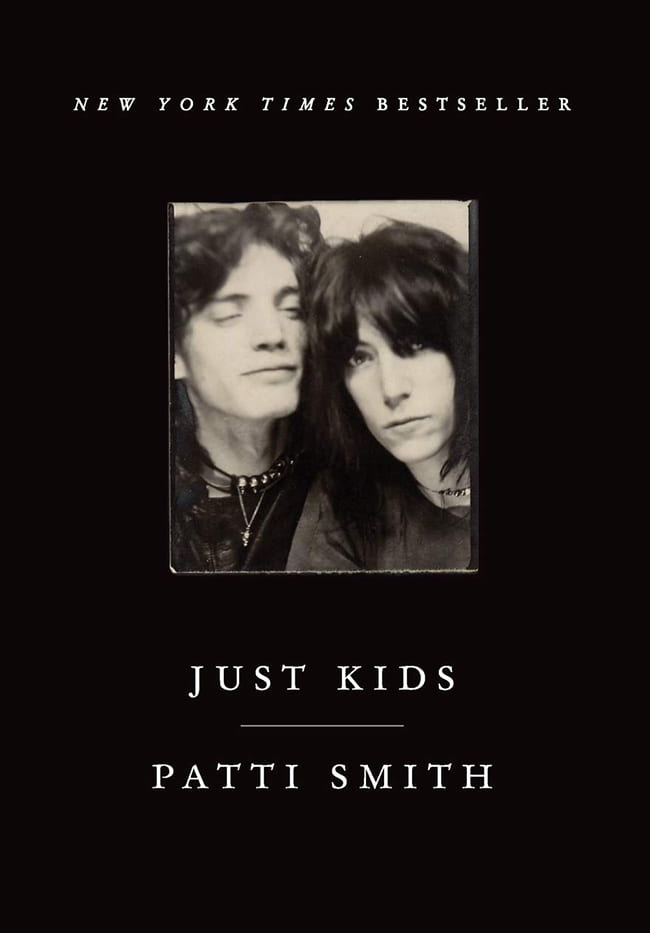

Shortly before the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s death in 1989, Patti Smith promised him that she would write the story of their relationship. But the great rock-and-roll poet didn’t do it right away. “Our story was obliged to wait until I could find the right voice,” she writes in Just Kids, the book by which she kept her promise. If finding the right voice took time, so did coming to terms with the limits of that voice: although she evokes Robert Mapplethorpe powerfully in these pages, there is no language powerful enough to bring her beloved friend back to life. With the grief of the one left behind, she asks, “Why can’t I write something that would awake the dead?”

The voice Patti Smith found to tell the story of her lover, friend, companion, and fellow artist is a religious voice that traces every creative impulse back to God: “Art sings of God,” she writes on the opening page, “and ultimately belongs to him.” It is a poetic voice, intent on finding the right words to describe a relationship that drew her into the “sacred work” of making art. It is a voice formed by bedrock childhood experiences of absorption and ecstasy, shaped by childhood’s stories: “We were as Hansel and Gretel,” she writes, “and we ventured into the black forest of the world.” Throughout, the dominant tone is one of gratitude.

Near the beginning of Just Kids, Smith records a memory from her very early childhood. She remembers seeing a swan rise into the air, filling her with “an urge I had no words for, a desire to speak of the swan, to say something of its whiteness, the explosive nature of its movement, and the slow beating of its wings.” That urge gives shape to the rest of her life. Years later, when she records “Up There Down There,” she holds her memory of the swan as she sings, imbuing her performance with the yearning to speak of what is just beyond language, to stand at the intersection of heaven and earth, to bring what is inside of her and what is outside closer and closer.

Patti Smith was the child of questing parents who taught her to pray, gave her books, and talked with her about art, practices that kept alive in her the desire she felt watching the swan beat its wings and fly. She cultivated her inner life through prayer (“my entrance into the radiance of imagination”) and reading. Fascinated with how absorbed her mother became in books, she placed her mother’s copy of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs under her pillow, trying to take in its meaning before she could decipher its words. Reading created new yearnings, intensified her desire to create, and eventually led her to New York, to Robert Mapplethorpe, and to her life’s work.

In 1967, at the age of twenty, Patti Smith moved to New York City. She had already studied briefly at Glassboro State Teachers College in New Jersey, given birth to a child who had been adopted, and worked in a factory (where she had been harassed for her devotion to the poet Arthur Rimbaud). Desperate not to get trapped in dispiriting work, she made a vow to the child she had given up and to Joan of Arc that she would make something of herself and moved to New York, longing “to enter the fraternity of the artist: the hunger, their manner of dress, their process and prayers.”

Patti Smith moved about New York City the way the great haiku poet, Matsuo Bashō, traveled northern Japan: full of devotion, deeply aware of the invisible presence of the artists who had walked the same streets before her. Second Avenue was “Frank O’Hara territory”; the spirit of Dylan Thomas still lingered in the Chelsea Hotel. Sleeping outside, often hungry, she was nevertheless held by the city like a child who had been blessed by a good fairy: “I sensed no danger in the city, and I never encountered any.”

Robert Mapplethorpe entered Smith’s life, as she put it, “like an answer to a teenage prayer.” They had met briefly a few times, but he appeared in Tompkins Square Park at precisely the moment she needed him. Trying to extricate herself from the company of a man who had bought her dinner and who seemed to expect something in return, she walked up to the beautiful boy she had met in a bookstore and asked him to pretend to be her boyfriend. Not even knowing each other’s names, they grasped hands and ran toward the life they both craved. Setting a pattern for many future evenings, they stayed up all night looking at art books and exchanging childhood stories. He gave her a drawing he had made on Joan of Arc’s feast day, the same day she had made her pledge to Joan that she would become an artist. “I understood,” she writes, “that in this small space of time we had mutually surrendered our loneliness and replaced it with trust.”

Smith and Mapplethorpe became lovers and bound their lives together through their shared practice of art-making. The absorption that had so fascinated her when she observed her mother reading she found again in Robert Mapplethorpe, whose capacity for sustained attention was immense and, for Patti Smith, deeply inspiring. One of the recurring images in her account of their relationship is of the two of them working side by side for hours in focused ecstasy, completely absorbed in the work of drawing, or making jewelry, or writing poetry. “One cannot imagine the mutual happiness we felt when we sat and drew together,” Smith writes. “We would get lost for hours.”

Deeply protective of each other, they quickly developed ways of living together that supported each other’s aspirations and protected each other’s vulnerabilities. They made sure one of them was always vigilant, watching out for the other. “It was important,” Smith writes, “that we were never self-indulgent on the same day.” When they only had enough money for one museum admission, one would wait outside while the other went in to look for both of them. They also seemed to understand the heart of the other’s vocation, even before they understood their own. When Mapplethorpe grew frustrated trying to make collages with cuttings from erotic men’s magazines, Smith told him to take his own photographs because they would be better. And when Smith began to feel that writing was not physical enough to express what she wanted to express, Mapplethorpe told her to perform her poetry, to sing.

Even as they began to separate from each other sexually, they remained devoted to each other. They both struggled with Mapplethorpe’s evolving homosexuality—“I was less than compassionate,” Smith writes, “a fact I came to regret”—but their relationship was supple enough to find new forms. They continued to live together, to make art together, to inspire each other. And even when they did finally move into separate spaces, with other lovers, they continued to spend their time together, sharing meals, making art, listening to music, creating films and photographs. “Nothing is finished until you see it,” he told her. “Robert was always my first listener,” she tells us, “and I developed a lot of confidence simply by reading to him.”

Their successes, born in many ways from their friendship, eventually took them away from each other. Smith toured the world with her band, bringing together poetry and music in a sound that was uniquely her own. Mapplethorpe stayed behind in New York, creating photographs that documented the human body and sexuality in ways that had not been seen before. Each had helped the other find the form in which their work would flourish. And each remained a presence in the other’s work. “When I walked on the stages of the world without him,” Patti Smith writes, “I would close my eyes and picture him taking off his leather jacket, entering with me the infinite land of a thousand dances.”

Robert Mapplethorpe was diagnosed with AIDS in 1986. At the time, Patti Smith was living outside of Detroit with her husband, Fred Sonic Smith, and her family. She returned frequently to New York to be with him. He continued to take photographs of her for record covers, and her husband commented, “I don’t know how he does it, but all his photographs of you look like him.”

When Robert Mapplethorpe died in 1989, Patti Smith sang a memorial song for him at a service in the Whitney Museum. She held a memory in the center of her performance: a beautiful boy, smoking a cigarette outside a museum, waiting for her to come out and tell him what she had seen. Now, she writes, she is listening to him—listening to the silence his dying created, “a silence that would take a lifetime to express.”

Stephanie Paulsell is Houghton Professor of the Practice of Ministry Studies at Harvard Divinity School. She is the author of Honoring the Body: Meditations on a Christian Practice (Jossey-Bass).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.