Featured

Immaterial Witness

An artist excavates the ground of memory and imagination.

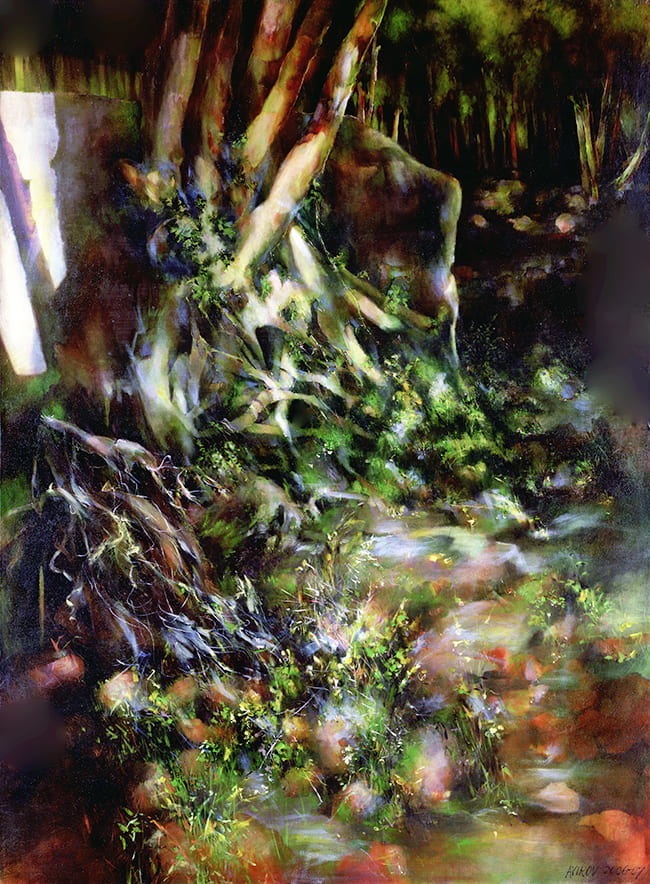

Madeleine Avirov, 100 Roots, Angeles Forest, oil on canvas, 60 x 44 in. (2007). Fisher Museum of Art, University of Southern California

By Madeleine Avirov

I remember as a child lying on my back in the grass of the failed garden behind the garage. Tall, tasseled grass, sky full of wind. I am hot and miserable, yet I dare not move until something happens to me. I owe all success, all failure to the exacting rules of childhood. My father’s Philadelphia street voice in my head: Everything in time. The grass is scratchy against my bare arms and legs. I startle at a grasshopper and stiffen with fear of more. But the heat lulls me into a half-sleep, and my sweat, like a solvent, effaces the boundary of my skin.

I wait, staring into the tangled precision of grass, willing myself small so that, like Alice, I might enter the green glade, knowing with the poet Charles Wright that “the line between heaven and earth is a grass blade, a light green and hard to walk.” I jumped off the swings a lot that summer, always in the hope of flying, but a larger hope lay in the sky itself, that its unseen hands could lift me clear of this life.

I date a certain knowledge from that time, a certain awareness of the hunger that the facts and appearances of the world could not satisfy, and a habit of making little worlds from whatever was at hand: masking tape, pipe cleaners, string, my mother’s wire hair curlers, the gray cardboard rectangles that came home from the dry cleaner inside my father’s shirts. In the everyday world I was a worried, urgent, solicitous child, but in the making of these things and the images they conjured, I found a sanctuary. Drawing especially would become a portable refuge, a crustacean’s shell—I was praised for it, even as I understood which drawings pleased (the pretty ones) and which did not, and kept the latter hidden. These hidden drawings prefigured the written notebooks and sketchbooks I began to keep as a teenager, part commonplace book, part diary, each a hedge against insubstantiality, the suspicion that I had not survived my months-long turn with scarlet fever at 7, and continued only as a disconsolate shade.

The drawings, the writings, were a way of gathering evidence of the unseen, the world within, a fulfillment of the urgency to render visible the invisible and to sow it across the uneven plain of my imagination. What grew there would bring neither love nor money, nor any negotiable skill, only the capacity to wait. It is waiting that teases out the intangible but durable inner aspect of all things—the deep form, wild and shy, and withdrawn from time, that stops my heart when, say, where I live in Los Angeles, in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains, a red-tailed hawk drops out of the sky above the freeway or a coyote materializes on an empty street before dawn. In these moments I am thrown back into the invisible world that everyday consciousness resists but that insists on its centrality to any truth, any image, worth bothering with.

In these moments I also see my life in miniature and remember my true vocation, which seems to have so little to do with the long and mostly dreary work history in which, over 40 years’ time, I have: scrubbed toilets and worked the grill in a fast-food restaurant; sliced bread, boxed cannoli, and bagged groceries at Catalano’s bakery; waitressed on Lee Road in Cleveland (with Vera, then in indeterminate middle age, a true broad of a vanished generation, who taught me to drink Scotch and insisted I go back to school); drawn charcoal portraits of children during 10-hour shifts at an old-time amusement park, as well as assorted car parts in the back room of a sign shop; managed a newsstand and its lonely customers shopping for foreign cigarettes and pornography; edited newspaper copy on the night shift and manuscripts at my kitchen table for the University of Chicago Press; shopped and cooked for a wealthy woman in a Chicago high-rise; hand-lettered wedding invitations in Copperplate calligraphy; walked the beige corridors for a dozen years in corporate publishing; illustrated magazines from the drafting table in my living room. The idea was that none of these jobs should require a real commitment, so that I could save myself for my serious work in the hours before dawn. But I produced little more than fragments and, come afternoon, struggled to stay awake. Until I was in my 40s, I was mystified by the artists I knew who approached their work as if it were a rational, upwardly mobile career. My mother and father were working-class, first-generation American Jews, born in the 1910s, reared without fathers. As their eldest child, I understood work as penance, meaningless except as a source of money, and my need to make art as an indulgence, even a disability. Like W. G. Sebald, who did not consider himself a writer, I did not consider myself an artist. “It’s like someone who builds a model of the Eiffel Tower out of matchsticks,” he said. “It’s devotional work. Obsessive.”

In the early 1970s I enrolled at Kent State University as a studio art major, but realism and instruction in craft (materials and techniques) being out of fashion, I studied these on my own, copying Michelangelo’s drawings from library books and walking the town with my sketch book. I was 19, barely acquainted with oil paint, and experimenting in the studio late one night, when my instructor was suddenly standing over me. I turned to see him cover his mouth with his hands. He said, “You should stop painting and get some help.”

The art school’s all-male faculty then privileged large-scale, hard-edged abstract painting and did not hide their disdain for the representational. I had been looking at James Ensor, at Edvard Munch, at Käthe Kollwitz, at the German Expressionists. What I remember about the painting I was working on that night is that it ran toward blue and that there were three heads which issued from one torso, and that I was in a state of high excitement because I had given form to the figures who haunted my imagination and cornered me in dreams. I destroyed it before walking home in the snow.

If art had been a way of charting my position in an unstable world, I reasoned then that writing could take its place, and for some years it did. I left school and would not return, but in the life others did not see I continued to read in coffee shops and library stacks, copying out passages from literature and poetry, religion and science. And I walked, memorizing light in its intervals, color in shadows, the logic of form in its twist and splay through the branches of trees. At 26, I moved to Chicago. The rooms I lived in were littered with false starts of stories, only a few of which ever saw publication.

In my early 30s, beset by a vision of myself at 90, aged hands still grieving the lost brush, I began again, with an apple-green ceramic pitcher, which I set on a white cloth and rendered in watercolor from multiple angles, in natural and incandescent light, on smooth hot-press paper and rough cold-press. I continued with house plants, the cats, my husband in an armchair; eventually, I stopped mixing paint on the palette, instead dropping each color singly onto wet paper, one into another.

These watercolors were technical exercises, working drafts. Yet while I was mindful of Monet’s advice to “try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field . . . and paint it just as it looks to you,” I was also feeling my way back to a memory of union with the objects of my perception, which required seeing every thing in its absolute particularity, as a thing living in itself.

At an early age I had grasped the technique of cross-hatching, which artists like Albrecht Dürer had devised to represent form, light, and shade. It was through line that I thought about objects, line through which I slowed down enough to find myself in the world I recognized as a fluid medium rather than one of separate entities. Now, I was after the same fluency with mass, with color, but it would come only slowly and, unlike drawing, be hard won.

A year or so after my return to watercolor, I rediscovered oil, in a Saturday class with a portrait painter. Some months later I would leave my marriage, and three months after that be fired from my job as a book editor. Before long I could no longer afford the class. I ran out of paint and canvas and could not replace them. I was 35. Early in the morning I walked along the edge of Lake Michigan toward home and passed by the homeless woman who slept in a cardboard lean-to under the viaduct beneath the Howard Street elevated train. I left quarters in the winding sheet near her head. That winter I hung bed sheets with safety pins over my curtainless windows. In my notebook, a half-dozen voices emerged who jostled side by side for space in my mind.

Years later, having gotten back together with my husband and now the mother of a son, I would talk with friends about that time as a necessary dark night, during which I located certain of the lies I had lived by. I did not bring up Simone Weil, to whom my thoughts continually returned that winter, the ardently French moral philosopher who refused to eat as she lay dying from tuberculosis in England in 1943. Privilege had gotten her out of occupied France, but the hunger strike that may have killed her—at 34—was a gesture of solidarity with her countrymen, many of whom were living on meager rations. What preoccupied me, however, was not her conviction that food in her mouth meant that someone had gone without, but her late coming to faith, to a God who would work through her only if she were “transparent,” got out of the way.

During the 1980s a domestic third world emerged in the streets as Ronald Reagan emptied the asylums. During the 1910s my father’s older sister entered an asylum in Philadelphia and presumably died there. Lingering that winter, less and less tethered to community, I dreamed one night that my aunt was the woman under the viaduct, and the next time I found her sleeping, at pains to obey the dream even as I was stricken by its violation, I bent down to her, as if familiarity had outflanked my inborn reserve and wariness and required me to save her—or join her. I did not know which.

I returned to painting in a Sunday life class at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I worked in oil, with models who held the same pose for three three-hour sessions. Although my instructor praised my drawing, he criticized my reliance on it and pushed me to work faster. In the hours that it took me to draw the figure on the canvas in charcoal, other students had completed a painting. I thought of these studies as exercises—one could spend a lifetime painting the human knee, let alone the head, and never be done, never know all there was to be known—and rarely brought one to completion, but my every effort was laden with a tension between my facility with line and comparative lack of it with mass and color. There was the tension in each mark, whether to restrain the hand or release it. And there was the tension of my ambition. I was caught in a net of memory and expectation woven from the facts of my history, which by now should have ended any and all thoughts of a destiny distinct from my uncomplicated if somewhat ill-starred relatives. But experience had forced certain obsessions upon me, among them a preoccupation with pattern, such that it often still takes a practiced effort of will to completely attend to another person in conversation, so distracted am I by the breaking and shifting planes and colors of the face and head. Add to that an early awareness of what Eastern traditions call the witness—the “you that is not you,” at once a kind of consciousness and presence which both participates in and observes the self. Slipping into this state as a child, a roomy place and off the clock, it seemed to me less invention than fact that I did not end at my skin but rather lived nested in an older self, who herself lived in a room off the future, hidden in plain sight. I was 11 when I drew my brown shoe. I was hatching the stitching around an eyelet when something like the aura before a migraine at once clouded my vision and gave me to see the vast and whole and implicate order on the table in the form of the shoe. It would happen again when I was 16, at work for three weeks on an Ebony-pencil portrait of my great-grandmother, who was more than 100 years old. I understood then that what we mean by appearances is only a fraction of what we see. In practice, this has come to mean working in silence or otherwise becoming still enough to sift the chaos of my moods and emotions from the vision’s strict inward progress.

Madeleine Avirov, Father in Bed, oil on canvas, 43 x 38 in. (2003).

About 10 years ago, guided by classic texts as well as Rembrandt and Titian, I began to experiment with oil-color mediums, with the techniques of glazing and scumbling. I gave myself permission to work on one painting for as long as necessary, whether weeks or months, a kind of luxury that would prove shocking in its degree of psychological nourishment and would strengthen my resolve to further resist the charge from all sides to hurry in all things. Thus was I reacquainted with the childish wish to make a world that, even in its fidelity to that which lies beyond the self, comes from the interior, and, coming from the interior, is sanctuary for the hidden self.

In this painting I am holding up my son—then six months old—under the arms. He twists away with pleasure as I kiss his neck. I chose this time-honored subject to test myself against it, to step self-consciously into the stream of art history, which, as a woman of little means, without academic credentials, without connections and the disposition to make them, I had little hope of entering. In my memory, the studio is lit up. I marveled at the seemingly sudden but unequivocal payoff from years of working from life, that in the absence of a model I could now refer to a snapshot, use it as a kind of mnemonic, then set it aside, and that—in the mysterious way of learning—color temperature, saturation, edge, hue, and the like now had a working relationship with each other on some back acreage of my mind, clearing the foreground for higher concerns. I didn’t have to think so hard about these things, endlessly, irritably reaching after fact and reason.

By building up the surface of the canvas transparently, I gradually translated into oil a method of applying paint I’d long used in watercolor, a method constructed from the study of tree bark, and the pictures of Cézanne, the Spanish realist Antonio López García, and the English figurative painter Euan Uglow. Now, I would lay down patches of color to build form almost architecturally, constructing the image as if it were a mosaic, each tile placed at a slightly different angle to the light.

There are certain settings, certain angles of incidence, that have long structured my imagination, their contours now so insistent that they would begin to resolve on canvas into rooms that my mother and father would not ever have chosen but could not part with. Bernard Malamud had put many of his Jews there: the cold-water walk-up set in what Philip Roth called “a timeless depression in a placeless Lower East Side.” Someone said about writing that if you are not risking sentimentality, you are not close to your inner self. In the three paintings that thus far had taken shape in these rooms (Father in Bed, 2003; Ma, 2004; Old Jew with Bird, 2009), I seemed to have come close. I hoped that by inserting my mother and father into invented interiors, whose every wall, window, garment, outsized crow would be self-evidently numinous by virtue of how I had described them, I could force open a door into the details of the past. And, even as I resisted art history’s injunction to interpret images, to find the narrative of what is being told, I hoped that the door thus opened might yield a story, one that was true in the way of a fiction being the great lie that tells the truth.

Many years ago I asked my grandmother to tell me about the shtetl, the impoverished village in Eastern Europe where she was born. She waved me away. “Europe. Feh!” she said, dismissing the continent entire. “You’re American born.” Her answer to a thousand years of displacement, privation, rape, cruelty, but I understood her to mean that the exile was complete. If loss is experienced, mourning accomplished, through detail, the loss is not only of a particular place—the village, the peasant house (I knew only that it had a dirt floor)—but of the very possibility of being placed, an eviction from even an imagination of home. For my grandmother and my parents, becoming American meant exchanging themselves for the future. For some of my generation it meant learning to be ashamed of one’s parents. The cost of their silence and my shame is in my inability to fathom my mother and father’s ordinary suffering, the small and dry exile at its heart, which has thronged my every day like a flock of hungry gulls.

(I must have been in my early 20s the one time my father sat for a portrait. After less than an hour I begged off, closing the sketch book without letting him see it, unable to bear his self-consciousness: he thought of himself as an ugly man, still bore the scars of the cystic acne he had suffered in his youth, the memory of the boils that grew under his shirt collar in the heat of the brewery furnace he fed in the 1930s. He said to me once, “I didn’t want anybody to look at me.”) By the time I completed Old Jew with Bird, I had come to accept that, as with the human knee, I would never be done. But during the many months I spent on each of these three works I was accompanied by a difficult knowledge, as by a second self who, having a greater depth of field, could at once see the work of art that must of necessity divine these people and the distance I would cross in order to gain it, the farther shore upon which my father, dead now five years, still burned in his incomprehension.

My working practice itself now began to cut through a decades-old knot of confusion about the function of light in painting. In traditional European painting, space is physical and light crosses emptiness and all things are perceived as “outside” and “over there.” As I work or walk, however, especially in the early morning, I become the thing I behold. (John Keats said that the poet “has no identity. If a sparrow comes before my window, I take part in its existence and peck about the gravel.”) Further, I had come to understand non-Western pictorial languages in which space is not physical but incorporeal, in which light is not something that crosses emptiness but is, rather, an emanation, a luminous healing force. As in the Russian icon, whose timeless space, opening out toward us, gathers up, even consumes, the eye, which itself then closes in prayer. The image—now wholly isolated in the mind’s eye—then, in holiness, can make itself known.

With the landscape Late Summer, Midwest (2004–05), this understanding would surface in a way that has marked my work ever since. I continued to work as before, building up the surface in a kind of geological process, but where previously I only built up, now it seemed that I was also digging down, excavating the image from the canvas, in which, like a fossil record, it was waiting to be found. At the same time I had become conscious of my effort, as, in The Elements of Style, William Strunk had said of words, to make every mark tell, and in its telling, to compose a whole with any number of the marks, scrapings, erasures surrounding it, so that wherever the eye might fall a door into the image would open.

In the autumn of 2005 my husband took a job in Los Angeles and we drove west from Chicago with our son and our cats. For the next 13 months, until my husband was laid off, I worked for the first time unencumbered by a day job, freelance work, or the necessity of finding one or the other to pay the bills. I had intended to pick up my work again with the series of paintings depicting my parents, but I was turned aside by a tree. A neighbor introduced me to a trail in the mountains not 10 minutes by car from home, and in the weeks that followed I returned, walking in farther and farther, until one morning I rounded a bend in a canyon and came upon a stream. The sun angled in from the canyon’s upper reaches, picking out a dense weave of roots, branches, and trunks somehow human in their uncertain growth out of the opposite bank. I have since come to know many California live oaks, some of whom live to be 250 or more, but this singular tree answered my anguish about leaving my native Midwest. It made me forget for a while the vast horizontals, the longing that only a long northern winter uncovers.

In the year that followed, during the hours that my son was in school, I did not answer the phone or the door, giving myself to the problems of a large canvas and an intricate landscape. I drafted and redrafted, advancing by endless recapitulation, hobbled by the difficulties of subordinating local color to certain effects of light in the landscape, as sunlight strayed across tree limb, root, leaf, grass blade, water, soil and stone, the trunks and crowns of distant trees, the crumbling concrete of a neglected retaining wall, the decay and leaf litter of the forest floor. Toward the end of the year that it took me to complete 100 Roots, Angeles Forest (2006–07), I hit a wall and could not resolve it. For hours, days at a time, I sat in the studio in anxious silence, making a tentative mark, stepping back, wiping it off, reaching for the state of mind a cigarette used to confer. Then waiting, watching my breath as the argument and counter-argument in my mind receded from flood tide, until I received a clear presentiment from the canvas itself of what had to be done. (I’m told that Philip Guston once said that when you first start painting, everyone is in the studio with you—your influences, your family and friends. One by one they leave, until it is just you. And then you leave, too.) In those hours, stripped of goals and reason, I submitted to a rapid, calligraphic mark-making that made the bending grasses and liquid depths come alive in a way that I could not have anticipated or planned. During this interval the title of the painting surfaced in a few lines from Rainer Maria Rilke: “Yet no matter how deeply I go down into myself / my God is dark, and like a webbing made / of a hundred roots, that drink in silence.”

Madeleine Avirov, Elegy for the Angeles Forest, oil on canvas, 48 x 24 in. (2009)

When my son was born I knew that he would force me into a more public life, if only on the playground, in ways I would find excruciating. Yet, at the same time I welcomed it. I could do for him what I could not do for myself. There was no similar motive power in my career. Although I had exhibited some before moving to Los Angeles, it was only at the request of a curator or a friend in charge. Over the years I had sent out packages of slides, applied for a grant, a residency, but the rejections were more than I could bear, each summoning a dark critic from the past, leaving me weakened and ashamed. Not even when my husband lost his job in the fall of 2006, or six months later, when we lost our health insurance, or six months after that, when his unemployment ran out and still I had not found work—not even Trader Joe’s would hire me—and we were served with an eviction notice and my husband lost his health and I came to believe that he would never work again—not even then could I risk repudiating the singular story that had ever told me who I was and what was possible. (With Czesław Miłosz, I suspect that “perhaps a memory older than our own lives, the memory of the species, circulates through us with our blood.”) The story was shot through with that memory—a hundred times familiar, like a city visited only in dreams, although I knew I had not seen it before. The motive power, although not in the career, only in the work, was that memory. And, where the memory was all weightless interiority and blind alley, and the work an attempt to give it bones and flesh, the career was all exteriority, all external authority, a judge who gave the work 15 seconds and for whom since childhood I had altered my clear vision in order to appease.

The memory revealed itself in dreams when I was young, in long and winding narratives set in northern latitudes where weather, always cloud- and wind-filled, figured prominently. The dead made regular appearances, sitting on hard-backed chairs in rooms with dark-painted walls or standing just inside partially opened doors or on railway platforms exposed to wind and rain. I rarely saw or heard them speak but was instead given to identify them in my mind’s ear, where they answered my questions about the future by giving me numerical puzzles to solve.

“Later on, you don’t see these things anymore.” This was the response of a Hasidic sage when he was asked by a student how God had made himself known to him. Similarly, I no longer dream at great length, and the dead visit rarely. The memory is less showy now, it comes through in the song of a bird, in the silhouette of a tree against the tinted light of early morning, in the granite cornerstone of a downtown building, dated 1906, seen through the window of a bus in the rain. The poet Irena Klepfisz, 2 years old when her father died in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943, asks whether there are “moments in history which cannot be escaped or transcended, but which act like time warps, permanently trapping all those who are touched by them.”

In 2008 an old-line Los Angeles art school hired me to teach figure drawing to inner-city teenagers, but by the next June the school’s donors had fled and the doors closed. Now, we live on my husband’s unemployment checks, on whatever freelance work either of us can pick up, on the sporadic sale of paintings from my studio. When someone asks why I don’t have a dealer, I say that I’ve had the happy problem of selling work almost as soon as I can make it. Then I change the subject, lest I fall into the chasm this question opens up between us—on their side there is a tomorrow, with, perhaps, a kitchen in it to remodel; on my side there is a door without a doorknob, such as one might find in the drawings of children in crisis.

So much has depended upon not drifting into what Gerard Manley Hopkins called (in the context of poetry) the “underthought,” that level of meaning that adds to, but may also contradict, the surface meaning, the “overthought.” Like a live broadcast on a delay—but hours, not seconds, later, the same day or that night—the underthought comes on as a rerun about money: what it will be like if the commission falls through or the check doesn’t come by Tuesday; what it will be like if my husband can’t get out of bed again today; what it will be like if we fall any farther behind on the rent and the landlord knocks on the door again, as he did when it was standing open in the heat of August, affording a full view of the table and three shallow bowls of spaghetti, to serve us with a notice to “pay or quit”; what it will be like to live in the car. . . . And, what it is like to be in the car (I have a car!), waiting for the light to change, while the homeless veteran with one arm stands on the curb with an upraised squeegee—especially on those rare days when I have a dollar in my wallet to give him and tell him to save his strength, but he insists on cleaning my windshield.

Last spring I completed the third in the series of paintings depicting my parents, Old Jew with Bird; then, in November, Elegy for the Angeles Forest, which I began only days before a man set fire to the foothills above Los Angeles. From late August through October, a fire hot enough to melt automobiles burned through 160,577 acres—nearly 250 square miles, or almost one quarter—of the Angeles National Forest, which ranges across the often steep and inaccessible terrain of the San Gabriel Mountains, a transverse range that rises between the Los Angeles basin and the Mojave Desert. I live in the foothills of northeast Los Angeles, and from the upper-floor window of our wood-frame house I watched through the wavering heat as the smoke rose and spread like a vast cumulonimbus cloud, raining ash and diminishing the quality of the air to what the Los Angeles Times called “unhealthful for all.”

I have not adapted to this place of little rain. I lack the faith of a native friend that, in winter, when the rains return, any one tree can drink enough to offset the thirst of the dry season. On summer afternoons I stay inside, emerging mostly in the early morning darkness to walk with my neighbor’s dog in the nearby Arroyo Seco, a dry riverbed that begins its narrow course in the mountains to the north. During the fire, the animals living in the mountains began to come down through the arroyo. I saw a blue heron, deer, more coyotes than usual, and considered the options left to those I did not see: to bear, opossum, raccoon, skunk, Nelson’s bighorn sheep, mountain lion, California red-legged frog, mountain yellow-legged frog, arroyo toad, bat, yellow warbler, Cooper’s hawk, San Gabriel Mountain slender salamander, California spotted owl, cactus wren, red-shafted flicker, scrub jay, two-lined garter snake: Escape the fire, burrow, or die.

In the days before the fire began I was sorting through photographs of Buckhorn Canyon I’d taken more than a year earlier, setting to one side those in which the late-May snowfall merged colorless into the sky. I settled on a massive conifer—whether Jeffrey or sugar pine I don’t know—that stood on a slope amid oak, incense cedar, and alder at 6,500 feet in the San Gabriels. Ralph Waldo Emerson called the woods “plantations of God.” The writer John Fowles said that trees were “very like the only form a universal god could conceivably take.” In his essay “Those Dark Trees,” Ptolemy Tompkins writes, “All trees say: Vanish into us.” This begins to get at my devotion to trees; it begins to get at my unrelieved despair, which persisted as the fire pressed on, as two firefighters died, as the charred body of a young bear was found clinging to a blackened stump rising from the gray waste. The consensus so far seems to be that the regional ecosystem, if only its plant life, will recover.

To mitigate the horror I felt at having to live a normal life at the edge of a cataclysm, I worked. Not to replicate that particular Buckhorn grove, or any place, but more to conjure a remembered dimension in which things are rearranged, local color is heightened, dimmed, ignored, and the surface in places remains broken and unfinished, in keeping with the broken world. On a late September Sunday afternoon, when the thermometer in the house hovered near 100 degrees and the windows were open to the smoke, I lifted the four-foot-tall canvas from the easel and, kneeling on the floor of the studio with a single-edged razor blade, scraped half of it, weeks of work, down nearly to the cloth. With less anxiety, however, than I would have had not so long ago, when I could not help but to obey impulses I did not understand, instead now nodding to the role of destruction in creation, and yielding to the work’s insistence that it show.

There is an imaginal world that I don’t believe in but that nonetheless has been the ground of the greater part of my happiness in this life. It is an opening out of the intermediate world where images reign, the “suprasensible world” spoken of by Henry Corbin, the scholar of Sufism, “which is neither the empirical world of the senses nor the abstract world of the intellect.” Here, things are less solid, less still, an openwork through which the God of all things rises like steam, or speaks, to whom Thomas Merton wrote: “My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. / I cannot know for certain where it will end.” Yet, somehow, I can see the way of the work. In Elegy for the Angeles Forest, I noticed my growing distaste for line, an impatience with hard edges in general, a desire to suppress them—to suppress, even renounce, my own draftsman’s virtuosity—in favor of mass, color, texture. Is this a final movement toward abstraction? Then I recall Apollinaire: “A full winter sun lights the hills / How beautiful nature is, how broken my heart.” Would that I could contain the beauty of the world so simply—and bear witness to our condition—but without telling the usual story, or telling one that isn’t afraid to show its daily reacquaintance with the emptiness at the end. It is an inward movement, but one that carries with it the loved things of the world.

This kind of geological process, of excavation, has long been at work in the practice, but where before I was all about the image—an image, down there, out there, back there in the incurable past, something somehow familiar—now my eyes are fixed more and more on that which is sensed rather than seen, or that which is seen only in the dark.

The goal is to get out of the way (or, as Simone Weil put it, “to see a landscape as it is when I am not there”). It is more than to become the thing that I behold—the tree on fire in the forest, the bending grass—and there to rest in the flickering knowledge that such refuge can be had but be unable to bring it back. To bring it back I have to walk the fault line between what fifth-century Christian monastics called the kataphatic, which finds God in created things through image, and the apophatic, which stresses emptiness, “imageless-ness”—I think about the canvasses of Mark Rothko, or, even, Rembrandt’s late self-portraits. These terms define two approaches to spirituality. I have borrowed them to define two approaches to painting. In The Solace of Fierce Landscapes, theologian Belden Lane writes that “apophatic spirituality has to start at the point where every other possibility ends. Whether we arrive there by means of a moment of stark extremity in our lives, or (metaphorically) by way of entry into a high desert landscape, the sense of naked inadequacy remains the same. Prayer without words can only begin where loss is reckoned as total.”

Madeleine Avirov is an artist and writer who lives in Los Angeles. More information about her work, and images of the paintings mentioned in this essay, may be found on her website, madeleineavirov.com.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.