Perspective

Filling in the Contours of ‘Unbelievers’

By Wendy McDowell

GIVEN THE FRANTIC 24-hour news cycle, we know it is highly unlikely that our biannual Harvard Divinity Bulletin will print material considered “timely” by most people’s standards. This is not something I bemoan, since I believe serious magazines occupy a much-needed space in our hyperspeed culture for curated content that takes at least one step back from current events.

So imagine our surprise as we were in the final stages of preparing this issue, and the Pew Research Center released a new set of survey data about the “rapid pace” of change in America’s religious landscape. The main thrust is that “the religiously unaffiliated share of the population, consisting of people who describe their religious identity as atheist, agnostic or ‘nothing in particular,’ now stands at 26%, up from 17% in 2009.”1

My first thought was: “Sometimes you luck out and hit the timing right!” But my decision to do a themed issue on the Nones was due to shifts in my own understanding of this group’s diversity. Here at HDS, the religiously unaffiliated have been increasing in the student body, and our students (including Angie Thurston and Casper ter Kuile, whose research and initiatives are detailed here) keep alerting us to the ways Nones are engaging in spiritual creativity and innovation.

In the greater Boston area, no one bats an eye if someone declares they are agnostic, humanist, atheist, spiritual but not religious, or that they could simply care less about religion. In a 2017 RNS column, Mark Silk pointed to a different Pew survey indicating that, for the first time, “a majority of us now say it’s not necessary to believe in God in order to have good morals and good values.”2 It’s a far cry from the rural farm community I grew up in, where a family we knew whose parents were avowed atheists was actively shunned by many of our neighbors.3

Though splashy news reports accompany each new bump in the unaffiliated, with their inevitable comparisons to other religious groups (“the Nones are now as big a group as evangelicals and Catholics!”), the coverage tends to be shallow. Pew’s latest headline reads, “In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace.” The narrative often seems designed to make those with religious commitments feel alarmed, or at least to experience a sense of loss.

Meanwhile, the increasing numbers of people identifying in various nonreligious ways are lumped together and labeled in terms of what they lack instead of what they actually believe and practice. As Katie Gordon puts it, instead of focusing on “diminishment and loss . . . we must ask what this trend in disaffiliation or spiritual fluidity reveals about spiritual life in the twenty-first century.”

The authors in this issue do not lament or apologize for these shifts; they dive deeper into why they are happening, where the unaffiliated are gathering, and how they are making meaning.

The authors in this issue do not lament or apologize for these shifts; they dive deeper into why they are happening, where the unaffiliated are gathering, and how they are making meaning—as individuals and collectively. Many discuss how the Nones are creating new forms of sacred community, while Quardricos Driskell explores how and why, so far, this group has not coalesced as a political bloc.

Other essays, including Christel Manning’s and the Q&A with Alan Lightman, reveal how science is a vital, secular source for many Nones (and for many, like Lightman, who identify as religious). Manning learns from interviews with elderly nonbelievers that rather than being “cold and hard and value neutral,” employing a science-based framework “can evoke a sense of awe and wonder.” Perceiving themselves as part of nature results in humility and a sense of moral responsibility toward other living beings.

Some find points of continuity with religious traditions, whether in Darryl Caterine’s description of the “sacramental imagination” and panentheism that is part of Catholic-Jesuit natural theology, or in Driskell’s suggestion that religious progressives and the religiously unaffiliated have more in common than they might realize.

Caterine, Driskell, Gordon, and Shira Hanau (who reports on nontraditional engagement by Jewish leaders) find hope in emerging religious and spiritual movements. At the same time, pulsing in many pieces, including the syllabus from “Apocalyptic Grief, Radical Joy,” is deep grief about the climate crisis. Dipesh Chakrabarty asks: “What happens when we are summoned by the general crisis of life—the possibility of another Great Extinction, caused by a species, for the first time in the history of the planet—to face the earth system that is critical to our and to other forms of life? What does it mean for the spirit to face . . . the planetary?”

Several authors, notably Mark Jordan, focus on how our categories cannot and do not “capture what they try to encircle.” Manning writes, “the way that people mix and match from various sources should make us rethink the boundaries between ‘religious’ and ‘secular.’ ” It’s the fuzzy, indistinct edges between categories that interest these thinkers, exploring, in Jordan’s words, the “spiritual echoes or overtones” in what gets categorized as “secular” spaces, movements, or protests. To wit, Ann Braude’s essay on three abstract artists whose creative journeys each involve “a process of spiritual evolution.”4

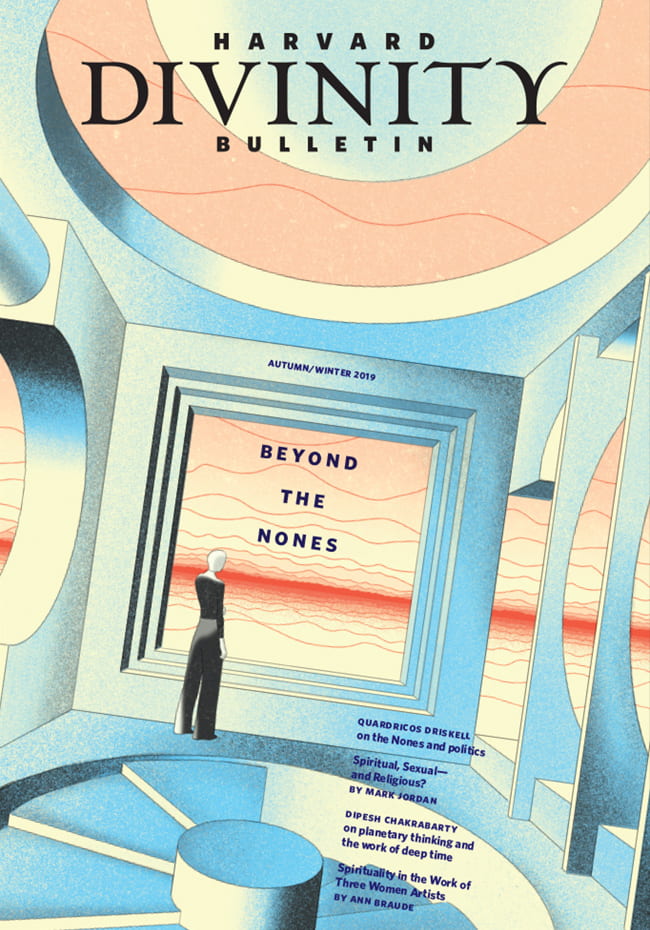

If, as Driskell suggests, we need to do more to bring the unaffiliated into the fold of our body politic, one step would be to recognize that the terms we use are not only inadequate, they serve to diminish or erase the complex experiences and multivarious practices of people who do not believe in God or gods. “None,” “nonreligious,” and “disaffiliated” tend to conjure an empty silhouette, a negative space.

As Jordan writes, we constantly need “to transform language in a way that opens new forms of life.” My hope is that this issue can spark our imaginations to reach for new language.5 I also hope it begins to fill in the contours of those empty silhouettes—Aubrey Wade’s portraits do this literally.

And if there’s one message I want readers to come away with, it’s this one, stated succinctly by one of Wade’s subjects: “I don’t believe in God but that doesn’t mean I don’t have beliefs,” Jan Pahl says.

Notes:

- Pew Research Center, October 17, 2019.

- “The Rising Belief in Moral Atheists,” Religion News Service, October 26, 2017.

- Make no mistake, there are still communities in the U.S., and in the world, where it is risky—or illegal—to admit you are an atheist or agnostic.

- LGBTQIP and artist communities have long viewed their work, activism, and relationships in spiritual terms. Jordan’s essay prompted my own fond memories of the Oscar Wilde Bookshop in New York City. Apparently, founder Craig Rodwell modeled the shop after a Christian Science reading room!

- We also need to expand our survey categories, removing their Christian and Protestant bias for church-based attendance, dogma, and scripture reading as measures of religiosity. This excludes many non-Christians, those who do not believe in a personal God, and polyreligious people.

Wendy McDowell is editor in chief of the Bulletin.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.