Perspective

Embodied Practices, (Re)lived History

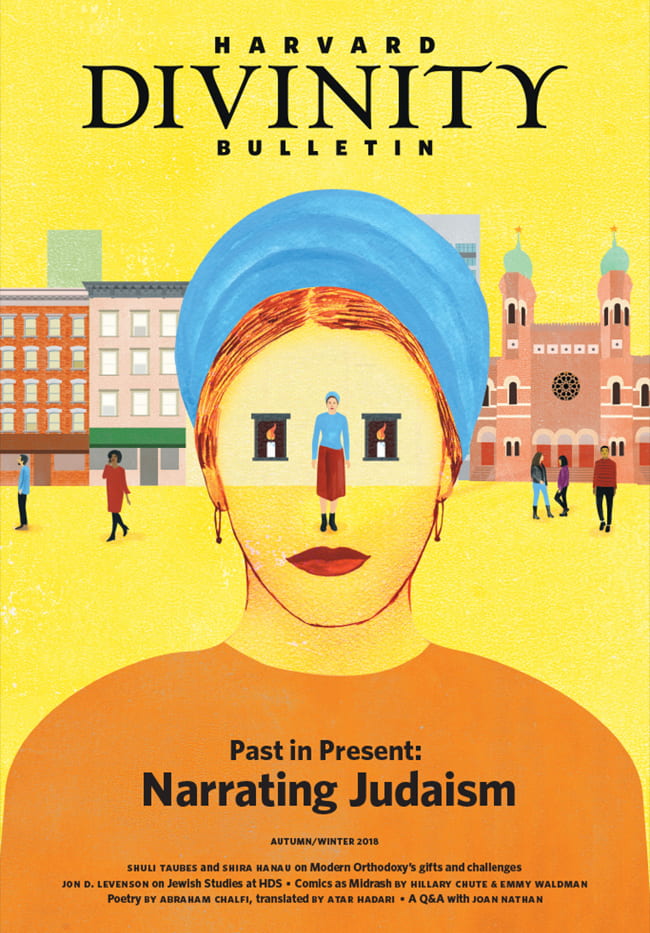

Illustration by Ellen Weinstein. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Rachel Slutsky

Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, is perhaps the most widely known Jewish holiday, yet it remains one of the least understood. For, while “atoning” might sound like a universal term, it fails to capture the practices of the day, and it is instead often comprehended through a Christological, faith-based lens of Jesus’s atonement on the cross. However, the observance of Yom Kippur is an example, par excellence, of embodied practice. In particular, the central part of the service is the ‘Avodah, literally “work” or “worship,” a term that often comes to describe cultic activity in the ancient temple in Jerusalem. As there is no present-day temple in which to slaughter sacrifices or burn incense, however, the ‘Avodah of Yom Kippur consists of the narrativization of the ‘Avodah, the liturgical recounting of the ancient practices that once took place. In other words, instead of replacing the Temple service with an entirely new series of practices, Judaism preserves the ancient service in verbal form, and it “reenacts” the events of the day by means of verbal recounting.

The liturgy of Yom Kippur is paradigmatic of a worldview found throughout Judaism’s texts and lived traditions. It is an outlook that combines memory and action, that results in a lived history, thus making Jewish practice and belief ever relevant in a changing world. Yom Kippur is one example among many demonstrating the way in which the past becomes an ever-present history—a history that is only in the past in a chronological sense, yet is relived, reenacted, every day, through every prayer, in every holiday.

Yom Kippur is one example among many in Judaism, demonstrating the way in which the past becomes an ever-present history–a history that is relived, reenacted, every day, through every prayer, in every holiday.

The liminality of Jewish history as both past and present is represented throughout this Bulletin issue and bespeaks the integral role that memory and embodiment play in the Jewish experience. As Hillary Chute and Emmy Waldman discuss, Jewish responses to the events of the Holocaust exemplify the reenactment of history in order to understand and absorb it. The graphic novel Maus is one such response, a text about memory, but it is a memory transformed: the memory is in the voice of a survivor’s child; the scars of the Holocaust are upon him, as well. And it is a memory re-embodied, this time with animal imagery instead of human.

Memory is as much a part of modern Jewish literary creation as it is of the Hebrew Bible itself. As Israel Knohl shows, the timeless story of Moses in Egypt has remained not only a potent symbol of man’s search for freedom, but also an example of scholarship’s ongoing quest to decipher and gauge the historicity of the Hebrew Bible’s most memorable narratives. And in Adam Afterman’s piece on Kabbalah, Jewish mysticism, an attempt is made to articulate the mystical notion of divine embodiment within every Jew in the temporal sphere of the Sabbath, Shabbat. Here, Shabbat is more than a “remembrance of the creation event,” but an internalization of the very Spirit that creates.

One might wonder, however, about the specter of the Holocaust, as its presence is felt throughout this issue. As Sarah Hammerschlag demonstrates, the Holocaust becomes a watershed moment in the recreation of Jewish identity; it served as the horrifying culmination of Jewish history, but also as the catalyst for a return to a pre-destruction Judaism, a Judaism within the land of Israel, thus spurring a rise in Zionist sentiment. And so, her focus on once-assimilated, nationalist French Jewry illustrates the inescapability of historical perspective, even for those most removed from tradition.

Bringing this sentiment to the fore is Avril Alba’s piece on the Sydney Jewish Museum in Australia, where physical artifacts from the Shoah help educate contemporary Jews and non-Jews alike about the perils of intolerance and hatred. Such a piece demonstrates the ways in which family heirlooms and inherited objects rise above sentimentality to have lasting universal significance for all who encounter them.

Of course, Judaism does not only require a recollection of the past, but also a reapplication of Jewish values and laws to the present. Shuli Taubes addresses some of these issues in her analysis of Modern Orthodoxy, plotting the development of an intellectually rigorous religious movement and demonstrating the ways in which its resulting hyper-intellectualism can be both boon and bust: Modern Orthodoxy might truly capture Judaism’s emphasis on learning, yet it can isolate those less intellectually inclined. These communal differences extend into the realm of politics as well. Shira Hanau’s coverage of the current political climate through the eyes of religious, yet politically liberal Jews captures the diverse, and often contentious, ways in which Jews understand their present moment through the lens of their historical legacy.

Courtney Sender’s exploration of Jewish womanhood during Rosh Hashanah gives expression to a delicate continuity found between the ancient, barren matriarchs and contemporary women. This contemporizing instinct is complemented by the poetry of Abraham Chalfi, particularly in his “Prayers of a Heretic,” which, as the title says, bridges a gap between the nonbeliever and religious devotion. And the present-day experience of things past is no better summarized than in Jon Levenson’s reflections on the history of Jewish Studies at Harvard Divinity School, an exploration of the ways in which the school’s religious identity has morphed, as well as stayed static, over its 200-year existence.

Entering into these cold months of winter, memory and its relevance to the present becomes a sustaining force through the change of seasons, the sleet, and the sunshine. This issue offers its readers a compendium of reflections on this reality and its significance for the Jewish experience of people past and present. The work that this issue does is to try and say something about Judaism’s contemporary encounter with its history, about the ways in which Judaism’s history transcends chronology. It is the hope of the editors that readers of this issue shall feel prompted to reconsider their own histories and traditions in light of present realities, and to find significance in their roots as well as in their contemporary branches.

Rachel Slutsky, guest editor of this issue, is a doctoral student in Hebrew Bible at Harvard University, where she specializes in biblical interpretation during the Second Temple period. She is working on a dissertation about the composition of ancient Jewish texts that were not included in the Jewish canon, such as the Book of Jubilees. She has presented papers at conferences throughout the US and the UK, and is also involved in interfaith dialogue and education.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.