Featured

Dis/appearing

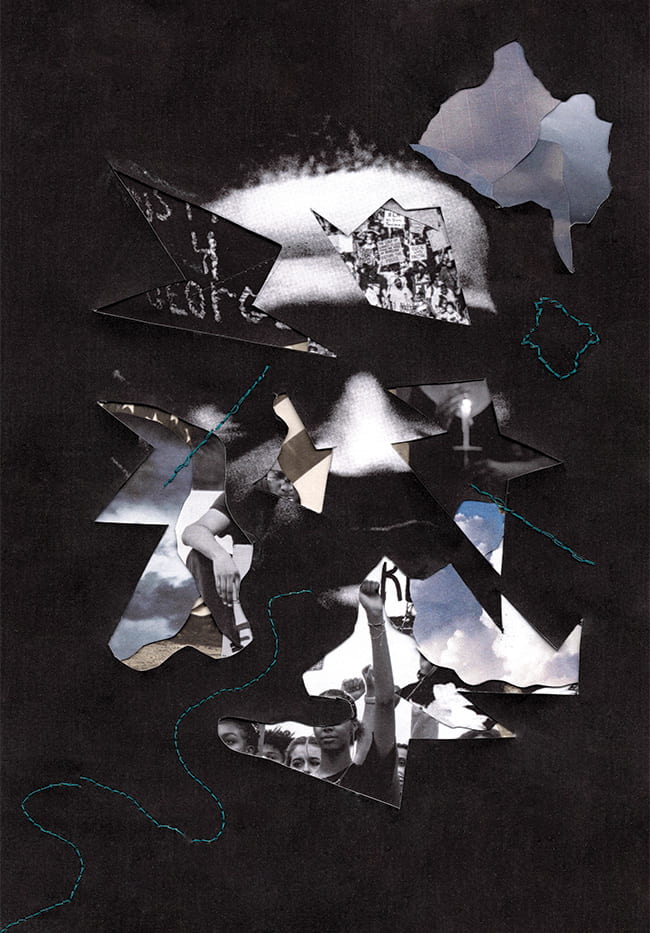

Black lives haunt the structures of American life.

By Biko Mandela Gray

They were present not as voices speaking but as the silence which is necessary to all speech. They existed as the pauses between words—those pauses which are necessary if speech is to be possible—and in their silence they spoke. —Charles Long1

The world is going badly, the picture is bleak, one could say almost black. . . . A black picture on a blackboard. —Jacques Derrida2

I want to think about “justice.” I want to think about its limits. I want to explore the ways that it can be violent—that it is violent.

I want to think about the violence of justice—the violence that is justice—because I am struggling. As legislators attempt to erase blackness and black life; as they denigrate critical race theory (something of which they know nothing about); as—and you all know this too well—men and women in robes salivate over admissions lawsuits that constitute yet another blow to the few civil rights black people have in this country; as black calls to and for redress are met with limp and vapid legislation—when anything is done at all—I am struggling to find justice.

No, that’s not quite right. I’ve found justice. But I’ve also found that I am not welcome under its sacred canopy. I have found that though I desire it, justice wants nothing to do with me. My desire is unrequited; I call, and it responds—with dismissal, platitudes, and the violence of surveillance and policing. I am not old, but I am older. And in being older, I have had to come to a sobering realization. I am not simply a threat to justice. I am what it militates against. I give it meaning. I call it into being through my death, through my very erasure.3

I do have personal reasons for wanting to think about justice. But I also have professional ones. I am, after all, a philosopher of religion, and it seems to me that justice is central to religion and its study. God—which is to say, the Christian God—guarantees it; the other gods sometimes call for it—though what they have in mind is often not what humans have in mind; and humans, in being faithful to God and/or the gods, believe, or are made to believe, in it. Suffice it to say, justice is not a political concept. Or if it is, it is not only a political concept. It combines ethics and faith; it is a praxis steeped in myth—whether this myth be national, cosmogonic, or theurgic. Justice and religion are, and perhaps have always been, good bedfellows.

And perhaps that’s the problem.

But I’ve gotten ahead of myself. I am a philosopher of religion, and in my training, I was taught that philosophers have argued about the relationship between God and justice for centuries. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz coined a fancy term for it: theodicy. As many of you know, theodicy is the line of thinking that tries to justify God’s goodness in the face of unrelenting and unremitting evil. Theodicy, then, is a structure of reason; it gives reasons—for why things are how they are, for why we should trust that things should get better. Justifying the state of affairs, providing reasons for why things are the way they are, or providing hope for something better in the end, theodicy encourages what philosopher of religion William R. Jones once called “quietism.”4 Theodicy shuts things down. It quashes resistance. It silences protest.

Yearning for a justice that will never come, or will only come in “the end”—whatever “the end” may mean—theodicy operates as a tool of cruel optimism.

But it doesn’t do it through brute force. Theodicy enacts its quietistic work through one of its constitutive concepts—justice. Yearning for a justice that will never come, or will only come in “the end”—whatever “the end” may mean—theodicy operates as a tool of cruel optimism; it gives us—well, some of us—hope in something that harms or kills us. To put this bluntly, theodicy is an antiblack enterprise. It is not friendly to black life.

I am not alone in saying this. In 1973, William Jones wondered if God was a white racist; in 1994, Anthony Pinn riffed off of Jones to remind us that, over the course of United States history, theodicy has produced the idea that black suffering and death have a “positive” or “redemptive” character; and Africana philosopher Lewis Gordon secularizes the theodicean question, calling our attention to the ways that white nation-states have become metonyms for God and God’s goodness and power—a goodness and power that required antiblack expiation and violence. As he puts it, blackness “is the theodicy of European modernity.”5

So, I am not alone. I stand on the shoulders of these thinkers; I seek to extend the path they have laid out. In different ways, at different times, and for different reasons, each of these thinkers has taught me that, at least when it comes to blackness and black people, theodicy is a futile and brutal enterprise. Or, to put it more bluntly—and philosophically—theodicy is a necessarily antiblack mode of reason.

If this is the case—if theodicy is antiblack—then “justice,” a concept central to theodicean thinking, to theodicean reasoning, is also antiblack. That’s my argument today; that’s my claim.

To make this claim, I will start with a story.

It wasn’t intentional. she didn’t mean it the way it came out. It’s just that the news was so good; justice had been served. And she was a political leader, after all; she knew she needed to say something. So, she called a press conference. Surrounded by black women—who were also political leaders—and living in a nation where religion and justice are intertwined, she stood there, in front of the cameras, and said the quiet part out loud.

Thank you, George Floyd, for giving your life for justice.

After thanking her God—and her Jesus—then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi siphoned a redemptive meaning in a scene of unrelenting and lethal brutality.

Many people, many black people, found this offensive. Finding this out, Pelosi “clarified” her remarks. She tweeted out:

George Floyd should be alive today. His family’s calls for justice for his murder were heard around the world. He did not die in vain. We must make sure other families don’t suffer the same racism, violence & pain, and we must enact the George Floyd #JusticeInPolicing Act.

It wasn’t a full apology. In fact, it wasn’t an apology at all. For Pelosi, George Floyd did not die in vain. His death was, indeed, a gift. A gift that may not have been given freely, but a gift nonetheless. A gift in service of justice. A gift in service of setting things right. Derek Chauvin’s conviction signaled—at least for her, anyway—that things were exactly as she thought. America will always set things right. A new bill would be signed. Reforms would come. It is horrible that someone had to die for all this to happen, but it would be a real missed opportunity if the country didn’t take advantage.

Justice was served.

New laws would be passed.

The country would be better off.

Thank you, George Floyd.

When I heard about Pelosi’s remarks—and then listened to them—I was one of those offended black people. As a philosopher of black religion, I had thought and written about “unwilling sacrifices.” Our deaths are gifts, but they are not given freely. They are taken, stolen, and then culled and stripped for whatever redemptive meaning they might have. When it comes to state-sanctioned antiblack violence, if we are martyrs—if we are martyred—this martyrdom is not volitional. It is unwilling. It is marked by choked cries of stifled breath; it is punctuated by cries to one’s mother; it happens when one sleeps, or as one’s car breaks down, or in front of a convenience store, or at a park, or in the street. To be murdered and then to have one’s death used for “justice”: that is black life here in the United States.

In the moment, I’ll admit I was angered, outraged, disgusted by Speaker Pelosi’s remarks. But time affords the space to think. It allows for a certain kind of clarity, even if it doesn’t allow for change. So when I was invited to give this lecture, I remembered this scene. And I also remembered a quotation in Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake. Quoting Joy James and Joao Costa Vargas, Sharpe writes:

What happens when instead of becoming enraged and shocked every time a Black person is killed in the United States, we recognize Black death as a predictable and constitutive aspect of this democracy? What will happen then if instead of demanding justice we recognize (or at least consider) that the very notion of justice . . . produces and requires Black exclusion and death as normative?6

Riffing off of James and Costa Vargas, Sharpe elaborates: “The ongoing state-sanctioned legal and extralegal murders of Black people are normative and, for this so-called democracy, necessary,” she writes. “It is the ground we walk on.”

Remembering this, I calmed my nerves. I slowed down. I thought about it. I sat with it. Today’s talk is the result of sitting with that scene and its effects. Thanking Floyd for losing his life might be “tone deaf,” but after slowing down, it is clear to me: Pelosi wasn’t wrong. Or, more precisely, she wasn’t inaccurate. The justice that was served was only made possible through Floyd’s death.

Call this a secular atonement; justice was found in and through the brutal and public murder of a man. In Pelosi’s speech, religion and justice intertwine to produce a public theodicy of antiblackness. It is brutal, but it is true. And though this country has moved on, I think it is prudent that we remain here.

In fact, I think “moving on” is precisely what makes theodicy so brutal. Theodicy provides the philosophical and theological resources to move on, to get over; by justifying the violence, by reminding people that things will be, or already are, good, theodicy—especially when it comes to black life—offers resources for forgetting, for letting go, for leaving blackness and black life behind. As I say in Black Life Matter:

The cops kill so much that it’s hard to keep track. So, you shed a tear, post something via social media, and move on. Or conversely—and on a wider scale—you draft a vapid piece of legislation, make a speech, “celebrate” or “bring awareness” to something, and move on. Once you’ve done your piece, the life no longer matters.7

The very act of moving on, of moving past or “getting over,” as Calvin Warren might say,8 is fueled in and through a theodicean structure of progress that justifies the deaths it supposedly “mourns.” Everything happens for a reason, we are told. Thank you, George Floyd, for sacrificing your life for justice.

I am staying here because I believe “moving on” is precisely what motivated Pelosi’s comments. I cannot determine what she wanted to do, but by naming the verdict as an act of justice, and by thanking Floyd for his death, she sanctioned and perpetuated what Charles Long might call a structure of “concealment” that is central to American religion—a structure that not only allows for white people (and, often, other nonblack people) to ease their conscience, but also allows for them to continually forget what they have done, what they continue to do, what they continue to allow to happen. Long puts it this way:

The religion of the American people centers around the telling and retelling of the mighty deeds of the white conquerors. This hermeneutic mask thus conceals the true experience of Americans from their very eyes. The invisibility of [indigenous Native Americans] and blacks is matched by a void or deeper invisibility within the consciousness of white Americans. The inordinate fear they have of minorities is an expression of the fear they have when they contemplate the possibility of seeing themselves as they really are.9

When refracted through Charles Long’s words, Pelosi’s public act of gratitude becomes an enactment of rhetorical violence, political repression, and religious concealment. So make no mistake: George Floyd’s death was not in vain. Not for Pelosi, and certainly not for this country. For without his death, there would have been no verdict. And without that verdict, there would have been no “progress.” No one was going to actually defund—let alone abolish—the police; that was a bridge too far. But “reforms” would happen. And in that verdict and in those reforms, “progress” will have been made.

Pelosi wasn’t inaccurate. She did the right thing. Which is to say, she did the American thing. An American thing that is, if we follow Long’s logic, a religious thing.

That commitment, that conviction—and yes, even that “progress”—are only made possible through the violent repression, eradication, and forgetfulness of black life.

Long spoke of this religious thing in terms of concealment and meaning; I speak of it in terms of theodicy. Either way, there is a commitment to, and conviction in, moving on in the name of “progress.” That commitment, that conviction—and yes, even that “progress”—are only made possible through the violent repression, eradication, and forgetfulness of black life.

How is this possible? What allows for this to continue? I’m still working this out, but my hunch is this: The American notion of “progress”—which is, as we have seen, a theodicean notion of antiblack concealment, erasure, and forgetting—is also made possible by a phenomenological structure of dis/appearance. As I’ve written, black lives “appear to us in the very moments in which they disappear.” They are “lost to us in the very moment we [come to] know who they are.”10 In other words, this structure of progress—theodicean and antiblack as it may be—is possible because black lives are, as Jacques Derrida and Rinaldo Walcott remind us, hauntological. We haunt the very structure of American life. And in so doing, we haunt the very development of “American religion” and its study.

Let us return, if we can, to the summer of 2020. protesters are filling the streets; Donald Trump is taking photo ops while paramilitary forces quash black resistance. The country is not only affected by a global pandemic; it is plagued by what too many news outlets called “a racial reckoning.”

This all happened because someone recorded a man choking another man to death in the street. The country did not know either of their names before June. I certainly didn’t. But the camera was enough. The recorded suffocation drew national attention. Floyd’s name became a hashtag; his face, a mural. His visage became a synecdoche for so many other police killings; it became a symbol of and for a certain kind of mourning and remembrance, as well as a certain kind of allyship. Money was spent and donated; corporations plastered “Black Lives Matter” everywhere. NBA players got new jerseys with terms like “equality” and “justice” on the back.

Think about it: We didn’t know George Floyd. Honestly, we don’t know him now. What we know, what we can only ever know, is a simulacrum; a hashtag, a photo, a mural, a painting—and, sadly, a video. Those of us who marched and protested for Floyd did so as an act of mourning; he was no longer with us; that could never be undone.

But we did speak his name. And then Breonna Taylor’s. And then Ahmaud Arbery’s. And before that, Michael Brown and Tamir Rice and Sandra Bland and Philando Castile and . . . The list goes on and on.

And that’s the point—the list goes on and on. With each new hashtag, with each new name added to the list, each new entry in what Katherine McKittrick might call a brutal “mathematics of the unliving,”11 we are reminded of the interminable, random-yet-somehow-predictable violence of cops killing black people. With each name added to the list, with each new hashtag and data entry, the other, older names, come back. Breonna Taylor wasn’t the first black person—let alone black femme—to be killed in her sleep in 2020; Floyd was not the first person to use his last breaths to claim, on camera, I can’t breathe. We had been here before. But this “before” seems to always come back. Or, to put it more bluntly: this country is haunted by the black lives who have been killed. Here is Derrida:

First suggestion: haunting is historical, to be sure, but it is not dated, it is never docilely given a date in the chain of presents, day after day, according to the instituted order of a calendar.12

Derrida’s discussion of haunting is complicated, and while I will be discussing him a bit more, I am not interested in demonstrating his brilliance or mine. I bring up this quotation to punctuate, to call to our attention, the way that hauntings work. And hauntings work, they only work, to the extent that they are a surprise, that they appear whenever and wherever.

But this isn’t the only thing that makes a haunting a haunting. What makes a haunting a haunting—what makes a haunting what Derrida will call “hauntological”—is the fact that the specter, the ghost, threatens to show itself. One cannot prepare for the apparition of a specter; and more to the point, the ghost’s appearance is always a reappearance. What shows itself can only show itself as a repetition, as a return, as a coming-back from wherever it once was.

Let me be concrete here and stop playing in the clouds. What I mean to say is this: with each name added to the list, the other names come back. Not the people; the names. The images. The simulacra of life that remind this country of what it has done and hasn’t done. What appears before us is never the actual life, the actual person. No. What appears before us is a hollowed-out apparition, a phantasmatic necrophany that we subject to our political ideologies and conjure up to confirm our goodness. Looking up at the sky, in the name of a God about whom she was unsure, Nancy Pelosi did not actually thank George Floyd. She thanked a name, the linguistic residue of a life once lived, the terminological surplus of a flesh-and-blood man, who was survived by a young daughter and a large and loving family.

How do I know this? Because she thanked him for doing something he never wanted to do. Thanking “George Floyd” was only possible because she couldn’t have—and probably wouldn’t have—asked him to willingly undergo what he did. As a representative of this country, as a national leader, Nancy Pelosi was haunted by George Floyd. He came from nowhere—which is to say, his death came from nowhere. His death “changed the world.” His death was an event. Again, Derrida:

Repetition and first time: this is perhaps the question of the event as question of the ghost. . . . Repetition and first time, but also repetition and last time, since the singularity of any first time, makes of it also a last time.13

Floyd’s death, that event, was a first and last time. It was definitely a last time; it punctuated, sharpened, set in sharp relief that he wasn’t the only one. But the verdict also contextualized that event; it was evidence that his death was also a first time—it was something different. Setting it in relief while giving it, reminding us that he wasn’t the only—while, well, being the only one, George Floyd haunted, and still haunts, the United States.

Floyd appeared to us, was shown to us—was revealed to us—in the very moment that he disappeared.

Well, that’s not quite right. George Floyd—like Breonna Taylor, like the infinite list that keeps on growing—didn’t haunt the United States. Floyd was hauntological. I keep saying this because it is important; we only know him because he died. Floyd appeared to us, was shown to us—was revealed to us—in the very moment that he disappeared. This “apparition of the inapparent,” this movement of nonpresence, this event of dis/appearance, makes us unsure of ourselves; it makes us wary. It leaves us bereft of our own cognitive resources. Note what Rinaldo Walcott says:

It is at the point of event and repetition that Black life is made both present and unbelievable. Black life generally finds itself in a repeated cycle of being spectacularized, often through visual representations in popular culture. . . . At the same time, and more specifically, the state violence that is repeatedly inflicted on Black people is seen as otherworldly and somehow not believable.14

And, again, Pelosi: “We all saw it on TV. We all saw it happen. And thank God, the jury validated what we saw.”

Pelosi has to thank God—again, there’s that theodicean logic—for the jury validating what “we” saw. What is the need for validation, for affirmation? Why the repetition of “We all saw it”? I want to suggest here that this repetition comes because Pelosi knows what Walcott knows, namely, that antiblack violence is “somehow not believable.” Walcott continues: “The video-recorded evidence and the body of the dead Black person are not enough to secure belief that what has taken place is, in fact, a murder. Thus, through a logic of disbelief, Black life is produced as both immediately present and immediately absent—appeared and disappeared.”15What Pelosi knows, what she cannot help but know, is that ironclad evidence is never ironclad; what appears can always be contested. (If you have time, look into the “force is unattractive” theory that was part of Derek Chauvin’s defense.)

Knowing this, Pelosi thanks God, Jesus, and George Floyd, for providing the conditions and occasion for a conviction. Justice has been served; there might be more work to do, but, at the end of the day, the hardest of hard parts is over. Securing the conviction—both of her beliefs and of Derek Chauvin—Nancy Pelosi declared victory. It was time to move on—or at least move forward. And this moving on, this moving forward, was only possible because Pelosi was haunted. Because George Floyd lived, and died, in a time “out of joint” with the normative world. Haunted, not simply by George Floyd, but also by the other deaths that his name silently invoked, Nancy Pelosi sent him on his way. She thanked him for giving his life. Which is to say, she sought to get over the hauntological presence that George Floyd signified.

George Floyd—like so many others—has dis/appeared to the American consciousness. And in their wakes, “progress” moves on. A theodicy is instantiated—and maintained. “Justice” is served. And that justice is—and remains—antiblack, haunted by the deaths it requires to sustain itself, and therefore requiring more deaths to keep its march of progress moving forward. As I said before, justice is antiblack. Always.

But, thankfully, that antiblackness is not the whole story.

In Significations, Charles Long underscores the power of silence. Silence is not simply the absence of speech, Long intimates. It is also the condition for speech. Attuning his attention to those who have been silenced, Long suggests that the very epistemological, political, and religious structures of Western modernity are only made possible in and through this silence—in and through the silenced.

But, Long reminds us, they remained. They remain. And they spoke.

They were present not as voices speaking but as the silence which is necessary to all speech. They existed as the pauses between words—those pauses which are necessary if speech is to be possible—and in their silence they spoke.16

In Specters of Marx, Derrida suggests that the most profound ethics—and a certain kind of justice—is only opened up by “learning to live with ghosts, in the upkeep, the conversation, the company, or the companionship, in the commerce without commerce of ghosts.”17 His way of doing this work was to develop—even he didn’t define—a hauntological discourse. And, as we’ve seen, hauntology is a profoundly generative tool for diagnosing and deconstructing the theodicean logic that structures an American religion of progress.

But, as I conclude, I want to gesture toward a different approach—one informed by Derrida to be sure, but more influenced by Long. Because in that quotation, Long gestures toward the very ethics, the very justice “without calculation and restitution” for which Derrida yearns, by turning our attention to those silent and silenced voices. Listen, Long seems to be saying; they are still speaking.

It is time we stay with the dead—not merely as an act of mourning but as an act of justice, an enactment that says: we haven’t moved on.

If we are to be ethical or more just, if we are to find a way of relating differently, I believe we must sit with those who have been silenced. We need to dwell with those who appear only to disappear. Which is to say, if any kind of radical justice is to be achieved, I believe we need to no longer enact a theodicy of “progress” but instead a hauntodicy of blackness. It is time we stay with the dead—not merely as an act of mourning but as an act of justice, an enactment that says: we haven’t moved on.

I cannot fully tell you what that looks like.

But, I am wont to turn to Toni Morrison for answers. At the end of Sula, one of the main characters, a woman named Nel, has lost her best friend, the woman for whom the book is named. Years after Sula has died, Nel finds herself struggling—not to remember, but to find solace.

She doesn’t. But she does find clarity. Walking away from the town drunkard, she finds herself reflecting:

Suddenly Nel stopped. Her eye twitched and burned a little.

“Sula?” she whispered, gazing at the tops of trees. “Sula?”

Leaves stirred; mud shifted; there was the smell of overripe green things. A soft ball of fur broke and scattered like dandelion spores in the breeze.

“All that time, all that time, I thought I was missing Jude.” And the loss pressed down on her chest and came up into her throat. “We was girls together,” she said as though explaining something. “O Lord, Sula,” she cried, “girl, girl, girlgirlgirl.”

It was a fine cry—loud and long—but it had no bottom and it had no top, just circles and circles of sorrow.18

All that time, I thought I was missing Jude. I do not have time to elaborate on all the details of this story. So what I will leave you with is this: feeling the presence of her long-dead friend, Nel finds clarity. And, according to Morrison herself, clarity is the very evidence of goodness itself. Sometimes that goodness will look like a warm embrace; other times, it might look like loud cries that have no bottoms or tops.

I can’t determine what this goodness, this justice without calculation, will look like.

But, recalling Speaker Pelosi’s speech, I can assure you what it doesn’t look like.

Notes:

- Charles H. Long, Significations: Signs, Symbols, and Images in the Interpretation of Religion (1986; Fortress Press, 1995), 65–66.

- Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International, trans. Peggy Kamuf (Routledge, 1994), 78.

- I wrote about this dynamic in my first book, Black Life Matter: Blackness, Religion, and the Subject (Duke University Press, 2022). There, I explored justice and its violence through specific encounters between black people and the police. Here, I will elaborate on what I wrote, but I will think about justice in different ways.

- William R. Jones, Is God a White Racist? A Preamble to Black Theology (Anchor, 1973).

- Ibid.; Anthony B. Pinn, Why, Lord? Suffering and Evil in Black Theology (Continuum, 1999); Lewis R. Gordon, “Race, Theodicy and the Normative Emancipatory Challenges of Blackness,” The South Atlantic Quarterly 112, no. 4 (October 2013): 729.

- Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Duke University Press, 2016), 7.

- Gray, Black Life Matter, 6.

- Calvin L. Warren, Ontological Terror: Blackness, Nihilism, and Emancipation (Duke University Press, 2018).

- Charles H. Long, “Civil Rights—Civil Religion: Visible People and Invisible Religion,” in American Civil Religion, ed. Russell E. Richey and Donald G. Jones (Harper and Row, 1974), 214.

- Gray, Black Life Matter, 3.

- Katherine McKittrick, “Mathematics Black Life,” The Black Scholar 44, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 17.

- Derrida, Specters, 4.

- Ibid., 10; emphasis of “the question . . .” is mine; other emphases are Derrida’s.

- Rinaldo Walcott, The Long Emancipation: Moving toward Black Freedom (Duke University Press, 2021), 45; my emphasis.

- Ibid., 46; my emphasis.

- Long, Significations, 65–66.

- Derrida, Specters, xviii.

- Toni Morrison, Sula (New American Library, 1973), 174.

Biko Mandela Gray is an associate professor of religion at Syracuse University. He is the author of Black Life Matter, available from Duke University Press, and he is also co-author (with Ryan Johnson) of Phenomenology of Black Spirit, out with Edinburgh University Press. This is a slightly edited text of the Greeley Lecture in Peace and Social Justice that Gray delivered at the Center for the Study of World Religions on April 6, 2023.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.