Dialogue

The Rise of the ‘Holy Spirit’ in Kabbalah

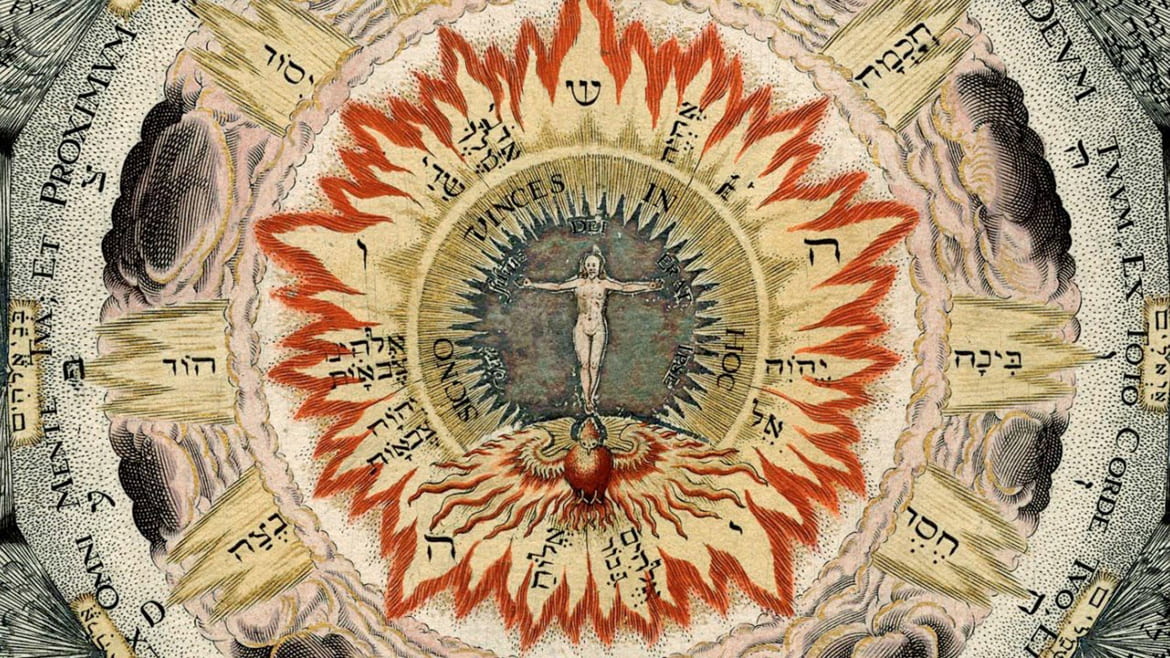

The rise of the “holy spirit” in medieval Kabbalah marks a dramatic development in the history of Jewish mysticism.Cosmic Rose engraving from Amphitheatrum Sapientiae Aeternae by Heinrich Khunrath (1595). Wikimedia Commons, CC-PD

By Adam Afterman

An important yet understudied element in Kabbalah, or medieval Jewish mysticism, is the mystical understanding of the Hebrew term ru’aḥ ha-qodesh, most commonly translated as “the holy spirit.” In the Jewish tradition, “ru’aḥ ha-qodesh” makes its first appearances in the Hebrew Bible in Psalms 51:13 and Isaiah 63:11-10 and becomes increasingly prevalent in classical rabbinic literature. However, it is within medieval and early modern Jewish literature, both philosophical and mystical, that the term “holy spirit” is elevated to prominence, as it becomes key for denoting the intimate communion between humanity and God, especially on the Sabbath. In contrast to Christian theology, the holy spirit was never methodically defined in classical rabbinic Judaism. From the surviving literature, two major theories regarding the holy spirit developed and continued to intersect in different stages of Jewish thought without any clear resolution. The first theory conceives of the holy spirit as an instrument or form of prophetic inspiration: Sometimes it was considered a form of actual prophecy, i.e., God communicates with his prophets through and by the holy spirit, while in other rabbinic discussions, it was considered as an instrument to communicate “sub-prophetic” inspiration, related to the rabbinic term bat qol, “a daughter of the (divine) voice,” i.e., an echo of the divine voice.1 The second theory, perhaps less known, conceives of the holy spirit as a personified metonym for God, as a manifestation of God’s being that “appears” and functions independently of any prophet. Ru’aḥ ha-qodesh is associated with another key rabbinic term, Shekhinah, generally translated as “the divine presence,” or “indwelling of the divine.” The first understanding seems to emphasize the inspiration the spirit effects in humanity, in which the spirit transmits God’s word but not his being or holiness, while the second identifies the term with God’s presence and being but his function remains independent of the prophet. Although Jews never officially determined what the holy spirit is, it is clear that the term is essential to Jewish thinking, just as it is for Christianity. The tension between these two Jewish understandings would continue to interplay and even merge within the development of Jewish philosophy and mysticism. The rise of the holy spirit’s status in Judaism is heavily indebted to the dramatic revolution of Jewish thought in the medieval era. The absorption of the surrounding Muslim and Christian cultures and of Neoplatonic, Neo-Aristotelian, and hermetic traditions led to new interpretations of the biblical and rabbinical traditions. The emergence of medieval Jewish philosophical and spiritual traditions included the development of a key idea absorbed from those three external traditions: metaphysical and spiritual overflow that originates in the metaphysical realm and descends into the human realm. Subsequently, this “new” overflow was identified with the biblical and rabbinic “holy spirit.” Many Jewish medieval thinkers thought of this overflow not as the direct word of God nor of his essence or being, but rather as a created metaphysical or spiritual “energy” that facilitates lower levels of inspiration and sub-prophetic experiences. At the same time, within the work of these same thinkers, we find the development of the opposite dynamic: the possibility of the return of the human soul or mind to its origin—that is, to the metaphysical realms and its reintegration. Both dynamics were correlated with two key Hebrew terms: the integration of the human into the metaphysical realms was associated with the biblical term devequt (cleaving), and that then led to the receiving of the overflow associated with the ru’aḥ ha-qodesh (holy spirit). While the human is not sanctified by this spirit, he definitely can be empowered and motivated to act and to communicate the revelations he receives to others. Within the Jewish tradition, the most developed articulation of this new term was introduced by the great twelfth-century Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides. Maimonides stated that inspiration through the holy spirit is a sub-prophetic phenomenon scientifically explained through the mechanism of the cleaving of the human intellect to the metaphysical (non-divine) intellect and its overflow, identified as the holy spirit. In contrast to “classic” prophecy, which ceased to exist in the distant past, Maimonides considered receiving the “prophetic-like information” through the “holy spirit” to be a relatively common phenomenon, attainable even in the present. Since the spirit is in constant overflow and not directed toward any specific individual, it is man’s responsibility to evolve to the state in which he might then receive the mental energy of the “holy spirit.” In this philosophical typology, the spirit is not conceived as directly transmitting God’s word, being, or holiness. With the emergence of Kabbalah at the end of the twelfth century, ru’aḥ ha-qodesh was no longer tied to the aforementioned metaphysical overflow, but rather to the divine overflow; that is, the kabbalists articulated a theory of a godhead conceived of as a body of divine energy radiating or emanating its essence “down” into the created worlds and the human realm. This overflow is imagined in terms of radiation or reflection of divine light and of the spirit overflowing from the divine to the world and ultimately to humanity.2 Here, we find these two rabbinic notions: While the spirit reaches the human and affects him, the spirit does so with the full capacity of God’s being; the effect is not merely the transmission of an idea or message, but rather the embodiment in the person and the fulfillment of the ultimate goal of the mystical life of the kabbalist, his fusion with God’s being. What is novel is the idea that by sending his holy spirit to human beings, God not only transmits his word, message, or ideas but his being and holiness as well. By enveloping the human, God dwells in the human in a form of mystical integration and fusion. When a kabbalist states that one has received ru’aḥ ha-qodesh, it does not mean, like Maimonides, that he has simply been “inspired” or experienced an intuition. Rather, it means that the divine essence and being has dwelled inside that man in a form of mystical fusion. Understood in terms of mystical union and embodiment, this medieval conception of the holy spirit led to an enrichment of the mystical path developed by the kabbalists. The central claim was that through the holy spirit, God ontologically dwells within him, sanctifying him. Through and by the fusion of the holy spirit in the human body, the human gradually assimilates into the divine. This mystical fusion takes place within all human faculties, including the body.3 What begins with the cleaving of the human soul with the godhead is completed with the indwelling of the godhead through the holy spirit in the human body. This embodiment of the divine in the human sanctifies and transforms the human into an organ or limb of the godhead, a divine and holy vessel—a “throne” or “chariot” for the dwelling of the divine. The mystical path of living in the holy spirit became a major focus of Jewish spirituality, and the kabbalists began to associate it with one of the most important Jewish practices, the observance of the Sabbath. In the Zohar, the primary thirteenth-century kabbalistic text, the Sabbath is considered a holy time in which the community of Israel embodies the holy spirit as a collective. The holy spirit is identified with a traditional rabbinic idea of an “additional soul” believed to dwell in the people of Israel during the Shabbat. The Zohar identifies the additional soul of Shabbat with the holy spirit that is further identified with the divine essence emanating from the godhead. Rooted in late Neoplatonic thought, the Zohar conceives of Shabbat as a sacred temporality; it is the holy spirit, a sacred essence of the divine that descends from the godhead and envelops the people of Israel. These mystical dynamics found their fullest expression in sixteenth-century Kabbalah. Kabbalists in this era composed practical manuals for mystical transformation leading ultimately to the ongoing indwelling of the holy spirit. Living in the holy spirit became the religious goal of many kabbalists of the time. They developed an intense, personal mystical practice in which Jewish rituals, commandments, and Torah have extraordinary purpose and meaning. This path also included some forms of mild asceticism meant to transform the harsh material body into a translucent vessel for the indwelling or incarnation of the spirit. It was thought that if a person is strongly driven, he can incorporate himself into the godhead and he may then draw the divine power, in the form of the holy spirit, into his body.4 While in the Zohar the holy spirit is conceived of as a “tube” spanning from the godhead to the human body, for the sixteenth-century kabbalists, the human soul is, in itself, such a “tube” or “branch” spanning from the human soul to an higher part or “root” of the soul that never descends into the human body. In this setting, the holy spirit descends from the infinite through this tube of the soul that connects the higher human soul with the embodied human soul. The process of elevating and integrating the lower soul into its source or “root” in the godhead is a process of self-realization in which the “lower” soul, associated with consciousness, is gradually detached from the dominance of the body and imagination and then gradually assimilated into the “higher” soul and the godhead. This cleaving is to the true self, the divine “double” or “twin” that never descends into the human body, an idea that was absorbed from Neoplatonic sources.5 The second phase is the active drawing of the holy spirit, identified with the infinite, from the godhead to the higher soul and then down through the “tube” that connects it to the lower soul; finally, the holy spirit is drawn into the human consciousness and into the body that becomes sanctified. The rise of the holy spirit in medieval and premodern Kabbalah marked a dramatic development in the history of Jewish mysticism and led to the development of a new and unique form of union with God. The fact that the kabbalists were able to creatively tie the new mystical ideals with key biblical and rabbinical terms contributed to the acceptance of these ideals in the mainstream Jewish tradition.6Notes:

- In many rabbinic sources, the term ru’aḥ ha-qodesh refers to this latter form of inspiration, which, even after the cessation of prophecy, was said to remain available in the Talmudic era and beyond.

- Accordingly, the kabbalists viewed the holy spirit as a direct overflow of the divine essence first “inside” the godhead and then from the godhead to the human. In this kabbalistic articulation, there is a return to the ancient idea that ru’aḥ ha-qodesh is God’s being and not merely a form of inspiration.

- For the kabbalists, the initial cleaving of the soul to the godhead leads to a fundamental receptivity of the human to the overflow of God’s divine essence, the holy spirit, which flows through the godhead from the Infinite (Ein-Sof), or the supreme source in the godhead, the “Crown” of God (sefirah of Keter), through the different gradations of the godhead, to the sub-divine realm, and into the human.

- The double-phased mystical fusion leads to his gradual sanctification. The spirit becomes a permanent link between the godhead and the sanctified human—a medium of ongoing embodiment of the divine through the holy spirit.

- On the background and origins of these ideas, see Charles M. Stang, Our Divine Double (Harvard University Press, 2016).

- I discuss this in my book “And They Shall Be One Flesh”: On the Language of Mystical Union in Judaism (Brill, 2016).

Adam Afterman is chair of the Department of Jewish Philosophy and Talmud at Tel Aviv University and a Senior Research Fellow at The Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

The Kabbalah understands the essential principle of judgement as that of limitation. The root of all acts of judgement is a desire to limit possibilities.

Watching the blessings in others lives is the greatest gift.

G-d Bless and Sincerely Grateful

How blessed I am to have stumbled (?) onto this essay on Kabbalah? I have been studying Kabbalah under the guidance of an inner voice whom I call Spirit, because he will not give e a name to call Him by, claiming that names can distract from the message or teaching. He came into my conscious life in an unbelievable way – many years ago, while I was alone, at night, on a frail sailboat, somewhere in th Southern Pacific Ocean – no, not Southern, for we were off the coat of Costa rico, so we were still in the NorthernHemasphere. I was on night duty, and decided to seek a psychic connection with a higher level of intelligence. I believed it was possible. I had read about mystics, and psychics. It was a reckles thing to d Practical Kabbalao, and I would not advise anyone to be as foolish, or as possibly disrespectful as I unknowingly was. It was a frightenenng experience, even though it opened the door to an educational experience that I would not have believed possible. I learned humility. But, back to this very informative essay by Rabbi Afterman, I was searching on line for a file – a document I had writtn about Spirit teaches Kabbalah, for my spirit teacher seems intent on sharing a future book on Kabbal Timeless Wisdom through me, but not just yet. We are still preparing to publish a book on Spirit Teaches I Ching Timeless Wisdom. Spirit’s books are designed for ordinary people, for simple seekers, such as myself. Three small books on “Spirit Teaches a Simple Seeker – The Art of Timeless Wisdom” have been published, after many years of struggle to not be overwhelmed and controlled by Spirit, and yet to serve the cause that he seems intent to serve, the future of humanity, for Life, or who/what some call God. Your essay has been a blessing and has helped me develop a deeper understanding of the history of Kabbalah. I seem to need to find and learn more on the subject, besides what I learn from Spirit. I’m blessed to have discovered C.J.M. Hopking’s “The Practical Kabbalah guidebook. I would be totally grateful if you could recommend other sources suited to a simple seeker, such as myself. Sincerely, Jean Whitred.

I am attempting to understand the mysticism of the great Kabbalists who have supernatural powers to divine Hashem’s actual meanings. There appears to be a reference to the Kabbalah in Hashem’s prophet Ezekiel.

Hashem describes the supernatural Kabbalah divination (וּמִקְסַ֥ם) in Ezekiel 13:8-9.

“Assuredly, thus said the Lord GOD: Because you speak falsehood and prophesy lies, assuredly, I will deal with you—declares the Lord GOD. My hand will be against the prophets who prophesy falsehood and utter lying divination. They shall not remain in the assembly of My people, they shall not be inscribed in the lists of the House of Israel, and they shall not come back to the land of Israel. Thus shall you know that I am the Lord GOD.”

Rabbi, Are you a believer in Kabbalah and divination?

The desire to be filled with the Holy Spirit is an invitation for one to return to the all and the all to return to the one. As a result of exploring the union with The Holy Spirit and walking back into the flesh the parallel of both becomes a way to understand what it is to be in my own will and then the divine will. Also the spiritual battle that occurred from the response of the enemy seeing Gods divine work in me has also made me able to acknowledge that which God is doing in this day for us to be aware of Satans punishment and allow my praise to be sincere to all .