In Review

A Lasting Impression

Examining biblical art in a secular society.

By William Dyrness

A recent exhibition at the Museum of Biblical Art (MOBIA) in New York City, “Biblical Art in a Secular Century,” sought to re-examine the assumption that modern art and religion have gone their separate ways. Given the received opinions about modern art, this is not an easy thing to do. It seems obvious to everyone that, as James Elkins claimed in his book On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art, “the separation has become entrenched.” But is this really the case? Has it ever been the case?

How does one go about addressing these questions? For much of the early period of modern art, the formalist literature dominating the conversation pointedly avoided any reference to the artists’ beliefs, or even to their personal lives. As Clive Bell wrote early in the last century: “To appreciate a work of art we need to bring with us nothing from life, no knowl-edge of its ideas and affairs, no familiarity with its emotions.” Following Bell, and later Clement Greenberg, modern artists and critics in their search for purity and concreteness did not encourage serious discussion of the relation between religion and modern art.

Things began to change in the last half of the century. William Rubin, director of the Museum of Modern Art’s department of painting and sculpture, wrote an important book on modern sacred art entitled Modern Sacred Art and the Church at Assy. The critic Robert Rosenblum described an alternative tradition of modern art deriving from the Northern Romantic tradition that was frequently religious in character in his book Modern Painting and the North-ern Romantic Tradition. Several major exhibitions focusing on the religious character of modern art were held, including, prominently, the 1986–87 exhibition in Los Angeles entitled “The Spiritual in Art.” Since then, religious subjects and references have become increasingly frequent.

But in the minds of most people—viewers and critics—during the rise and prominence of high modernism, religion makes no appearance. There are of course good reasons for this assumption: the scarcity of church patronage of modern styles, and indeed its frequently active hostility toward modern art, and the inward turn of the Romantic period, which focused on the artist’s search for transcendence through art that made no use of traditional religious symbols provide some ex-planation. This exhibit at MOBIA focuses on a number of religious subjects mostly overlooked in the study of high modernism. These issues are worthy of study in themselves, but here I want to focus on three case studies of more particular influence: the rise of high modernism in Russia, France, and the United States. The question is: has religion had more direct influence on the rise of modern styles themselves?

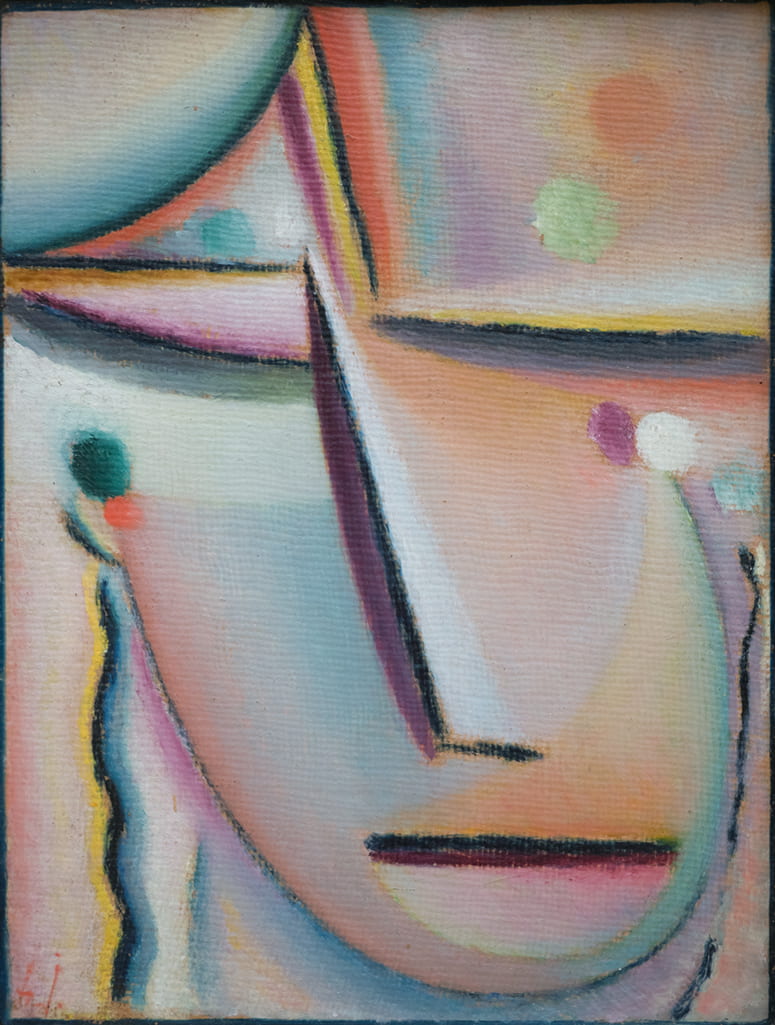

Meditation “The Prayer”, Alexej von Jawlensky, oil on cardboard, 15.5″ x 11.8″ (1922). Wikimedia Commons, CC-PD.

Russia: The Mystical Image

For artists living in Russia at the turn of the twentieth century, escaping from religious tradition was easier said than done: Orthodoxy inhabited the air they breathed. While for much of the later nineteenth century, artists and intellectuals were estranged from Orthodoxy, the decades beginning in 1890 experienced a revival of mystical faiths, and art came to be seen in religious terms—whether in traditional or nontraditional forms. Many artists of that period would have endorsed the sentiments of the symbolist philosophers of the day who insisted, as John Bowlt has noted in “Esoteric Culture and Russian Society,” in The Spiritual in Art, the “arts are of a temple, cultist origin; they derived from a certain organic unity in which all the parts were subordinate to a religious center.” It is not too much to claim that the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich was a consequence of this religious rediscovery—it is not by accident that Malevich and his colleagues were often called apostles. Malevich’s Suprematist works often resembled icons and were presented as such. Critic Camilla Gray, who routinely ignores the religious aspect of any work she discusses, admits that Malevich was not concerned with visual impressions but with the relation of the person to the cosmos. His “Black Square and Red Square,” for example, shows the concentrated attention that is demanded of the viewer to induce the feeling of infinity he sought. The influence of theosophical writings led Malevich to move beyond traditional Orthodox faith. Still, his art represents a continuing spiritual quest.

Another Russian artist who was drawn to the spirituality of the Orthodox icon was Alexej Jawlensky. After studying at the St. Petersburg Academy, he came to Munich where, like Malevich, he fell under the influence of Wassily Kandinsky, and was associated with the Blaue Reiter group. From 1917, when he settled in Switzerland, he focused on the human face, which he felt represented the “distant imprint of a divine power.” This led to Jawlensky’s powerful late series entitled “Sacred Faces.” Clearly informed by the facial image of icons, Jawlensky’s faces gradually became more stylized until all that was left were the lines formed by the eyes and by the nose, creating a cross. Warner Haftmann noted in his book Painting in the Twentieth Century: “The religious impulses of the Blaue Reiter were brought to full fruition by Jawlensky.” As in the case of Russian music of this time—seen, for ex-ample, in Rachmaninov’s Vespers, the work of Malevich and Jawlensky cannot be fully understood apart from their religious con-text. John Bowlt argued, in an essay ac-companying the exhibition “The Spiritual in Art,” that one of the prominent sources for the spiritual regeneration in Russian art during this period was Russian Ortho-doxy and its liturgy. The deep structures of religion continued to influence these modern artists; the traditions continued to be deeply felt even if they were nontraditionally observed.

The Vision After the Sermon: Jacob Wrestling with the Angel, Paul Gaughuin, oil on canvas, 28.7″ x 36.2″ (1888). Wikimedia Commons, CC-PD.

France: The Sacramental Image

It is possible to argue that Post-Impressionist artists in France, while preparing the way for the revolutions of the twentieth century, also believed they were making possible a new kind of religious art, one that expressed their Catholic sensibilities. Fifty years ago, the prominent French critic Joseph Pichard argued that during this period a few painters of the soul—Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, for example—were opening the way for the development of a truly sacred art.

Lying behind these painters were the innovations of Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Van Gogh’s religious background, in its particularly Protestant form, clearly motivated his violent search for transcendence through the empirical world. Rosenblum has noted in his book Modern Painting that “with Van Gogh,” like other Northern European painters, “we feel anew the kind of passionate search for religious truths in the world of empirical observation.” But it was Gauguin who was to have a more far-reaching influence on the renewal of sacred art in France, and even beyond. Maurice Denis, a leader in the 1890 Symbolist movement in France believed Gauguin allowed the Symbolists to escape the dilemma of the real and the ideal posed by David. It was Gauguin, Denis noted, who saw painting above all as a colored canvas. This retreat from idealism opened the way for artistic form to become symbolic or sacramental. Denis and other Symbolists—drawing, I believe, on their Roman Catholic heritage and on the notion of the sacramental presence of Christ in the Eucharist—developed the idea of the flat surface to mean that painterly media could evoke religious feelings. Denis defined Symbolism as “the art of translating and provoking states of the soul, by means of relations of colors and forms.” For Denis these states of the soul clearly had a spiritual dimension, and the symbolic power of art reflected the underlying reality of Catholic liturgy and the sacraments. In 1888 Gauguin visited Van Gogh in Arles and claimed to have found there a source of the beautiful in a modern style. He was surely referring to the influence of Japanese cloisonné style and the decorative work of Emile Bernard, but the religious values of Van Gogh must have played a role in their conversations.

That same year Gauguin painted his well-known “Jacob Wrestling with the Angel,” a painting that conveys much of the new possibilities for religious art that the Symbolist period introduced. Its images—of a distant figure with the angel, and the peasant women in the foreground—are meant to stimulate feelings and values, which Gauguin and his circle liked to refer to as “dreams”: one part remembrance, one part longing, and a final part free-floating imagining. As Gauguin said, of pictorial arts: “Painting is the most beautiful of all the arts; it is able to collect all the sensations, and with these, each one can, by means of the imagination, create a story, and at once have the soul invaded by the deepest memories. . . . [It is] a complete art which gathers all the others and completes them.” In the minds of the Symbolists, this imaginative alchemy of lines, colors, and objects greatly expanded the development of sacred art, rather than impeding it, and this impulse became critical for the revival of religious art in later decades. Joseph Pichard said of Gauguin: “haunted by the sacred [he] reinvented a language for sacred art.”

The significance of this period for the subsequent developments of modern art is widely recognized, of course. But often overlooked is the way this discovery of symbolic depth, depending as it did on Catholic sacramental ideas, prepared the way for a significant flowering of religious art both in France and beyond—associated above all with the names of Jacques Maritain and Georges Rouault.

Cotopaxi, Frederic Edwin Church, oil on canvas, 48″ x 85″ (1862). Wikimedia Commons, CC-PD.

The U.S.: The Expressive Image

In the United States, the gulf between modern secular assumptions and the religious presence is assumed to be, if any-thing, greater than in Europe. With the possible exception of Russia, the United States is surely the most religious nation of those we have surveyed. And yet, at least in the modern period, art developed under purely secular influences—mostly Euro-pean. Or so we have been led to believe. But this common perception may need re-thinking. Clearly, the strongly Protestant and Puritan traditions in the United States had enormous influence on its culture, even up to the end of the nineteenth century. And in the earliest periods the Puritan influence was not as inimical to visual art as often believed—especially in the area of landscape and portrait painting. In the nineteenth century this religious tradition proved to be influential for painters of the Hudson River School, consistent with the Protestant inclination to seek the divine in the created order. With Thomas Cole and, especially, Frederick Church, landscapes are often pictured as allegories of religious truth. Church in particular believed that nature was as much the word of God as the Bible, and that God was working both in human and natural history. Influenced by Ruskin’s Modern Painters and by William Turner’s paintings, Church painted monumental landscapes as types of God’s work in American history “to create his holy nation.” Painted during the Civil War, “Cotopaxi” portrays nature as a reflection of the regeneration of the United States, which Church hoped would result from the war. The painting was, David Huntington argues, the “Guernica” of the Civil War.

A younger contemporary of Church’s who was to have more direct influence on twentieth-century art was Albert Pinkham Ryder, the only American artist Jackson Pollock claims meant anything to him. Nourished by the Bible and Shakespeare, Ryder was a visionary artist whose work captures a poetic vision of the forces of nature. In “Jonah,” Ryder creates a mystical seascape that recalls the novel Moby Dick, published a generation earlier. The potential of the created order, and especially the forces of nature, to carry a supernatural meaning was a long-standing American impulse, and one that was to influence artists seeking their way in the artistic idioms of the twentieth century. Marsden Hartley recalls an experience with Ryder’s work which shows something of the impact of this artist. Seeing Ryder reminded Hartley of his first experience reading Emerson’s Essays:

I felt as if I read a page of the Bible. All my essential Yankee qualities were brought forth out of this picture . . . it had in it the stupendous solemnity of a Blake mystical picture and it had a sense of realism besides that bore such a force of nature itself as to leave me breathless. The picture had done its work and I was a convert to the field of imagination to which I was born.

The responses of Hartley and Pollock to Ryder are significant. They show first how artists working in the center of European developments—the American-born Hartley exhibited with the Blaue Reiter group in Berlin—could feel a strong affinity to American traditions, even to their religious impulses (Pollock was also drawn to Native American spirituality). But Ryder’s mystical qualities also suggest a subtle difference between the nineteenth century of Ryder and the twentieth-century artists. The mysticism of the nineteenth century was al-most uniformly antimodern. Thinkers as different as Walt Whitman and William James felt modern developments were resulting in the loss of a spiritual center. Following Emerson, these thinkers and the artists they influenced tended to look at art as a means to move beyond one’s rational consciousness and become one with the work, in a way that recalled religious rituals.

But the mystical and ritual leanings of American abstractionists show that, for all their modernists tendencies, these artists were also firmly rooted in American sources. As the exhibition “The Spiritual in Art” demonstrated, both European and American abstract artists, initially at least, worked from spiritual motivations. But in the development and practice of abstraction, artists reflected their—very different—American or European setting. As John Golding put this in his book Paths to the Absolute: Mondrian, Malevich, Kandinsky, Pollock, Newman, Rothko, and Still:

The European is concerned with the transcendence of objects, the American is concerned with transcendental experience. . . .The early European abstractionists had achieved their absolutes, had purified and purged art, by in a sense painting themselves out of their pictures, whereas the Americans were trying to achieve some of the same ends by painting themselves totally into their canvases, by stepping up and into them, even in an odd way by becoming art.

This comment reflects the different attitudes toward art in these places, of course, but it also reflects their very different views of religion. Religion in the United States has always placed the focus on individual will and private experience. It is not surprising, then, that American artists, even when working in the modern style, could express religious motivations in their work. No one put himself more clearly into his work than Pollock, and the extent of religious motivation in his work has probably not been fully appreciated. In some cases at least, the purity and concreteness that Clive Bell and Clement Greenberg celebrated may have spoken more about their own values than about those the artists brought to their work.

To claim that religious traditions are alive and well in contemporary art would be claiming too much. But at least one smaller—though significant—claim may be advanced in conclusion. Clearly, religious influences have motivated many important artists and movements in the modern period, despite the ambivalence they may have felt toward those traditions. Can the achievements of Picasso, for example, be thoroughly understood apart from his own Catholic childhood? What about the Catholicism of Cézanne or of Warhol? It might also be the case that central aspects of religious traditions—the Orthodox icon in Russia, the Catholic sacraments in France, and Protestant spirituality in America—have played a role in artistic innovations. But this implies a further possibility that might be explored: perhaps these innovations may in turn have an influence on these religious traditions. Traditions, after all, are not fixed entities; they are always under construction.

Renato Poggioli wrote in The Theory of the Avant Garde: “Tradition itself ought to be conceived not as a museum but as an atelier, as a continuous process of formation, a constant creation of new values, a crucible of new experience.” The Enlightenment led us to assume that art and religion were mutually independent. But perhaps the mutual influence of art and religion continued, unnoticed, in spite of this assumption. The MOBIA exhibition suggested that these evolving traditions may still enrich one another, as they have done so often in the past.

William Dyrness is Dean Emeritus and Professor of Theology and Culture in the School of Theology at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. He is author, most recently, of Reformed Theology and Visual Culture: The Protestant Imagination From Calvin to Edwards (Cambridge University Press).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.