A Look Back

Redefining America’s ‘Race Problem’

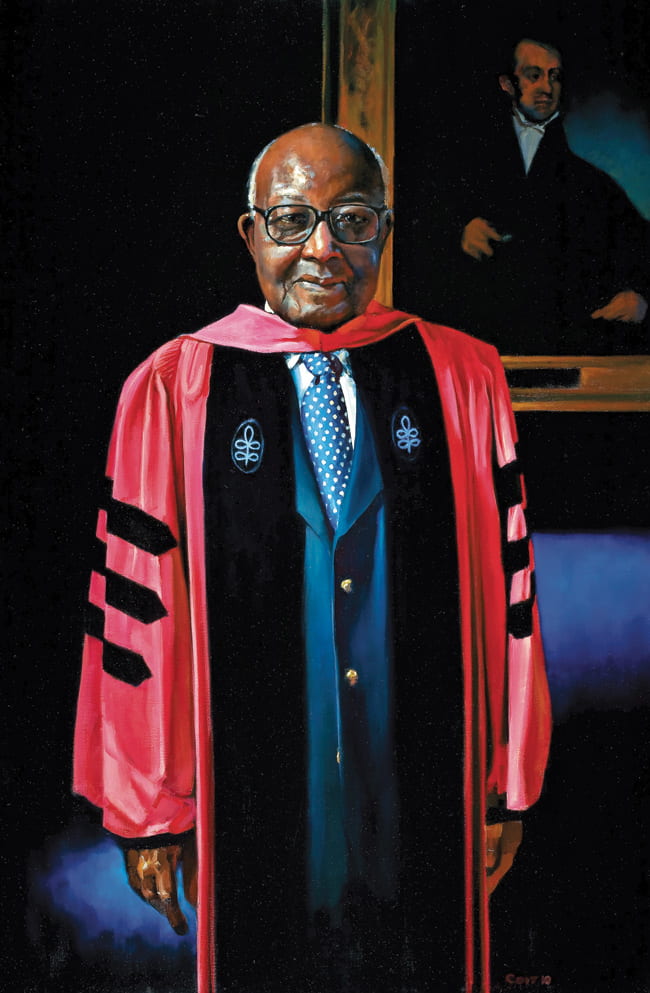

Preston N. Williams portrait, 2011. Harvard University Portrait Collection

By Preston N. Williams

The Negro in America has finally succeeded in making America aware of the true nature of her racial problem.

The seal of that victory is the Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders:

What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.

White racism is essentially responsible for the explosive mixture which has been accumulating in our cities since the end of World War II.

Just as President Eisenhower and many Americans have refused to acknowledge the Supreme Court’s school desegregation decision of 1954, so also have President Johnson and many Americans refused to accept this document. Nevertheless, the American substitute for the Delphic oracle—a Presidential commission—has asserted that white racism is the main cause of America’s civil disorders and of its race problem.

It would be naïve for us to think of this report as simply a response to the riots of 1967. It was a response to what America has called its Negro problem, and it was a firm statement urging the redefinition of the problem. The problem is not black America; the problem is white America, white racism. But the timing of the report is exceedingly important for our evaluation. It was issued precisely at that juncture in the civil rights crusade when the black man’s action was shorn of its halo of righteousness. Assigning culpability to the black man would have been easy, for he had performed his most provocative act. Yet this Establishment committee of white prestige leaders and two non-militant, non-radical Negroes asserted in the face of a public calling for “law and order” that white racism is the cause of America’s civil disorders and of her racial problem.

The Negro had made Americans redefine the racial problem and see the country through the eyes of its most oppressed minority. This, I submit, is the most salient fact about the contemporary Negro in America. He is being seen as he wants to be seen. The invisible man has been made visible, the stereotype has been replaced by a living man. . . .

The civil rights movement can be interpreted as the attempt of Negro citizens to receive their rights as individual citizens. Negro revolution or rebellion points to the attempt to form organic communities, which as communities demand self-determination and freedom and which as communities impose certain duties on their members. Success here has been at best suggestive. No one unified Negro community has come into existence in any local area and none should be expected to emerge. . . .

Nonetheless what has occurred is not without fruit. A rebirth of the conception of a people has resulted from these efforts at building a community. Negroes have come to speak of themselves as a people with a vocation and a mission. Their history and culture are being recovered and revived, and serious work is being undertaken in an effort to reconstitute social institutions. Black has become beautiful; the slave heritage has become a teacher against cant and for compassion and endurance; and the disabilities of the present are prods to develop a new, more sensitive, and world-embracing ethic.

The most pervasive note struck in the cultural revival is the desire for identification with Africa. I regard this as a romanticizing stemming from powerlessness and alienation. In point of time the Negro may know that he came to the American shore before the Mayflower, yet in assimilation he feels that he is a first-generation immigrant longing for the home to which he cannot return, Africa.

Even though return is impossible and Africa is too vague a homeland, Africa does symbolize the single most important component of the new solidarity—the Negro’s blackness, his not yet fully known culture and tradition. It points to his desired integrity, freedom, and autonomy. Africa is the Negro’s “soul,” America but his dwelling place. The major issue is how to be both an American and a Negro.

An ordained Presbyterian minister, Preston N. Williams was Acting Dean of HDS in 1974–75, and was the Houghton Professor of Theology and Contemporary Change from 1971 to 2002. Williams wrote this essay while he was the Martin Luther King, Jr. Professor at Boston University School of Theology.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.