Featured

The Karma of a Nation

Pledge of allegiance at Raphael Weill Public School, San Francisco, California, April 20, 1942. Children in families of Japanese ancestry were evacuated with their parents and incarcerated for the duration of World War II. Photographers were commissioned by the War Relocation Authority to document the daily life of Japanese Americans immediately prior to incarceration and at the concentration camps. Dorothea Lange, National Archives NWDNS-210-G-C122

By Duncan Ryuken Williams

When my advisor, Masatoshi S. Nagatomi, passed away suddenly during my last year as a PhD student at Harvard, his family asked me to sort out his office. In the process of cleaning, I found a bundle of yellowed pages buried among books and dissertation drafts. Eventually, I identified the pages as Professor Nagatomi’s father’s diary from Manzanar, one of the War Relocation Authority camps that housed over 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry during World War II. Nagatomi’s wife asked me to translate the diary, so I began. Soon I was immersed in stories of Japanese American incarceration, stories of a time when Asian American Buddhists were perceived as a threat to national security, in terms of race and in terms of religion. Today, Buddhism may not seem like a threat to American national identity. But turning to this history of the conflation of religion and race might help us understand the recent rise in anti-Asian sentiment that has led to harassment, violence, and even death.

On February 27, 2021, in my own community in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo, a fire was set in Higashi Honganji Temple, a Buddhist temple just a couple of blocks over from my own. Windows were smashed, lanterns were broken, the temple walls were vandalized. In this climate of increased animus toward Asian Americans, based primarily on race but also on religion, there has been a spike in vandalization of Buddhist temples, especially in Southern California.

Just a few months earlier, in Orange County, six different temples were vandalized over the course of one month. At the Huong Tich Buddhist Temple in Santa Ana, in a neighborhood known as Little Saigon (home to the largest Vietnamese population outside of Vietnam), people used black spray paint to desecrate statues of buddhas and bodhisattvas. They even sprayed the word “Jesus” on the back of them.

When I spoke with temple member Thai Viet Phan, the first person of Vietnamese background to be elected to the city council in Santa Ana, she told me: “It’s beyond trespass. It’s beyond vandalism. It’s a hate crime targeted at the Vietnamese American Buddhist community, and we will not stand for that.”

These incidents are part of a much broader pattern of targeting people of Asian descent: verbal harassment on the streets, elderly Asian American people being pushed over. In January, 84-year-old Vicha Ratanapakdee was taking a morning walk around his neighborhood in San Francisco, when a man came out of nowhere and violently threw him to the ground—just for fun. Ratanapakdee died of his injuries. In a powerful photo, his daughter sits in the Nagara Dhamma Temple holding up a portrait and praying for her father. He was a devout Buddhist practitioner.

In the Asian American community, we are worried about our elders facing violence when they simply walk down the street. Some have attributed this to the COVID-related spike in anti-Asian violence that we see in rhetoric like “China flu”—the culture has permitted these attacks on Asian people. And I think there’s some truth to that. But this racialized violence also has a very lengthy history.

Japanese Americans arrive at the Santa Anita racing track where they lived before being moved to concentration camps. Arcadia, California, April 5, 1942. Clem Albers, National Archives NWDNS-210-G-A7

When I first came to the United States as a 17-year-old immigrant from Japan, I landed in Portland, Oregon, and attended a small college there. I then learned that our rival school across the way was called Lewis and Clark College and that the local NBA team was called the Portland Trail Blazers. Through these names, I began to learn a version of American history populated by pioneers and trailblazers, people moving ever westward.

I later became a faculty member at UC Berkeley, which I learned was named after George Berkeley. Allegedly, when the regents of the university were gazing across the Pacific, looking west, they remembered the closing lines from Berkeley’s Verses on the Prospect of Planting Arts and Learning in America:

Westward the course of empire takes its way;

The first four Acts already past,

The fifth shall close the Drama with the day;

Time’s noblest offspring is the last.

This is the story of the America I encountered: one of westward expansion of empire. And this expansion was justified by God: God ordained not only the westward movement but also the takeover of Indigenous peoples’ lands and the importation of enslaved peoples from Africa to build this new nation.

I would learn about this version of America, but I would always be bothered by it because it was a story of an America that is essentially and solely a white and Christian nation. But this wasn’t the only America I knew. What about people like Nagatomi or me, I wondered, people who emigrated from Japan? That wasn’t our story of becoming American.

In contrast to Berkeley’s poem of westward expansion, in 1942, Reverend Nyogen Senzaki, a Zen Buddhist priest, wrote a poem from a horse stall in a racing track called Santa Anita, euphemistically named an assembly center. The track still exists today, a bit east of downtown LA. Senzaki was writing this poem to his sangha, which was part Japanese, part Japanese American, part Latinx, and part white American. And he addressed the poem specifically to the members who weren’t Japanese, the members who had been left behind while Japanese Americans were rounded up and transported to camps in Wyoming. He wrote:

This morning, the winding train, like a big black snake,

Takes us as far as Wyoming.

The current of Buddhist thought always runs eastward.

This policy may support the tendency of the teaching.

Who knows?1

It’s a little bit tongue in cheek, but Senzaki had a very playful mind. In this poem, Senzaki references the idea of the eastward advance of Buddhist teachings. In Japanese, we call this tendency bukkyō tōzen. This belief appeared in Japanese texts as early as the late eighth century and has its origin in a prophecy the historical Buddha made just before his own passing: that after his physical presence was gone, the dharma would remain and would inevitably be transmitted eastward. Originally, this eastward advance was seen in the movement of Buddhism from India through China to Korea to the islands of Japan. Some saw the movement of Buddhism from Japan to the United States as a continuation of that eastward trajectory.

Families boarding buses to the Tanforan Assembly Center. The father of these children was a Buddhist priest interned by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. San Francisco, California, April 29, 1942. Dorothea Lange, National Archives NWDNS-210-G-C421

Senzaki puts a spin on this to discuss his move from LA to Wyoming, from the horse stall he was placed in during his initial incarceration to the concentration camp at Heart Mountain. And we can see this eastward journey more broadly in the history of Asian American identity and belonging in America. Many Asian people first traveled to Hawai‘i and then to the Pacific coast and then continued on eastward, whether forced or by choice.

This is a different story of America than one of westward expansion. It offers a different vision of America that we can continue to imagine. When Ta-Nehisi Coates writes about reparations, he often talks about the need to reimagine the nation. Reparations, for Coates, are about reckoning with the past and reimagining a future nation. Buddhism can help us change our perspective and engage in this work of reimagining. It can help us see what we haven’t seen before. And that can offer us a way of moving through the legacies of racial harm.

The history of Japanese American incarceration during World War II is certainly a history of racial harm. But it is also a story of the ways that race and religion are often conflated. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the very first people to be picked up were Buddhists. The first person to be arrested was Bishop Gikyō Kuchiba, a Buddhist priest and the head of the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist sect in Hawai‘i. The second was the head priest of the Taiheiji Temple, a Zen temple near Pearl Harbor. You might think that the U.S. government would target Japanese consular officials or people with clear ties to the Japanese government. But even before martial law was declared, U.S. intelligence forces deemed Buddhist priests to be the highest threat to national security.

Buddhist temples had been under surveillance for years. Even prior to the Pearl Harbor attack, the government kept secret registries of “dangerous” individuals, many of whom were Japanese American Buddhist leaders and community members. The FBI placed people like Bishop Kuchiba in a category called Group A—a group thought to be the most dangerous and who would be interned in the event of war. Being neither white nor Christian, most Buddhist priests were placed in Category A, while Japanese Christian ministers were not.

Crates of personal belongings are sorted in the central square at the concentration camp. Individual owners identify their belongings and provide addresses for delivery of the crates to their barracks. Heart Mountain concentration camp, Wyoming, September 19, 1942. Tom Parker, National Archives NWDNS-210-G-E124

Where does this idea of Buddhism as a threat to American identity come from? If we look back in Asian American Buddhist history, we can see this conflation of religion and race very early on. The first Buddhist temples and communities in America emerged with the arrival of Chinese immigrants. Whether through working on plantations in Hawai‘i or constructing transcontinental railroads, Chinese immigrants were building America. Yet, very quickly, they came to be seen as a threat to national identity and security. They were portrayed as invading the nation and setting up a heathen despotism in San Francisco, and their presence triggered rhetoric around the need to build a wall around the United States, a symbolic wall shutting off the Pacific. And the slur that was used was the “heathen Chinee”—they were seen as racially unassimilable and religiously unacceptable as non-Christians.

One of the people to defend the Chinese was Frederick Douglass, a former slave, abolitionist, and great African American thinker and orator. When he was asked if he favored Chinese immigration, he said, yes. And when asked about citizenship, he said he favored that as well. When asked about voting rights, he said, yes. Douglass talked about this because he understood America as a civilization that was not about isolationism but about families, nations, and races that come together to compose something he would term a composite nation.

This is a very different vision of America than one of singularity and supremacy, one that positioned America as a white, Christian nation. This is a very different vision of what it means to be American than the one put forth in the 1881 Chinese Exclusion Act and subsequent legislation that targeted specific groups of people based on racial and religious exclusion.

View of barracks with Heart Mountain in the background. Heart Mountain concentration camp, Wyoming, March 28, 1943. Yoshio Okumoto, Dencsho Digital Repository DDR-HMWF-1-467 (Archives E-4)

In the face of these efforts toward exclusion (and in the face of the notion of Christianization as Americanization), many Japanese American Buddhists asserted their right to exist in America as Buddhists— to maintain their identity in a land that claimed to be founded on religious freedom. Reverend Yemyō Imamura, the bishop of the largest Japanese Buddhist sect in Hawai‘i, argued powerfully for the need not only for religious freedom, but also for ethnic multiplicity. He thought that targeting and censoring Japanese religious thought “contradicted the Founding Spirit of America. . . . America esteems freedom, equality, and independence, spiritual independence to the utmost. It never asks for spiritual servility.”2

Imamura was a wonderful pluralistic thinker and very much ahead of his time. At the time, in the early 1900s, Hawai‘i was one of the few territories in America that didn’t have anti-miscegenation laws, laws set up to prohibit marriage into the white race so as to ensure that the white race remained pure. As a Buddhist priest in Hawai‘i, Imamura discussed this intermixing in a positive light: he said that children of mixed blood were the future. They would develop and prosper. He placed his hope in hybridity.

These early voices give me hope about a different vision of America than the ones that were depicted in the propaganda and rhetoric of the time: posters, for instance, of “yellow peril” showing White Christian territories as a beautiful land illuminated by a cross that was being threatened by an ominous, black cloud carrying an image of the Buddha. This sentiment continued into World War II, when Japanese were depicted as sword-wielding and Buddha-worshipping samurai riding atop a military tank threatening America. Buddhism—or at least Asian American forms of Buddhism—represented something very un-American, and perhaps even anti-American, a threat to the very notion of the nation.

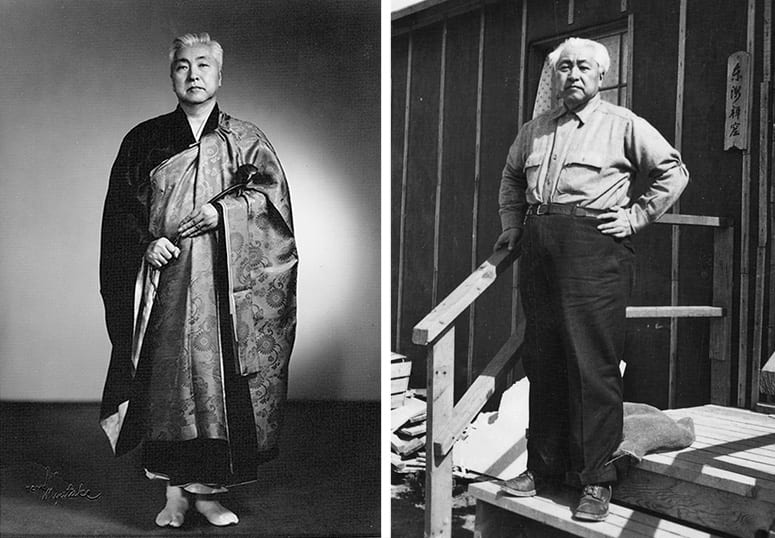

Left: Portrait of Nyogen Senzaki prior to incarceration. San Francisco, California, January 4, 1942. Right: Nyogen Senzaki at the Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming, July 4, 1943. Ruth Strout Mccandless Collection on Nyogen Senzaki, Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA.

A couple of months after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which permitted the military to round up anybody of Japanese ancestry—anyone with even a single drop of Japanese blood. Japanese Americans were viewed as such a threat that even children and infirm grandmothers were placed in internment camps. Mixed-race infants abandoned at orphanages were no exception.

After Japanese Americans were rounded up, they would arrive in what were called assembly centers—like the horse stalls at Santa Anita or livestock centers near Seattle. These centers were like prisons. Guards would check for contraband: weapons, cameras, any publications written in Japanese, books of haiku poetry, and Buddhist sutras. All of these objects and texts were considered dangerous with two exceptions: Japanese-English dictionaries and Japanese-language Christian Bibles. These two were considered American enough to be permitted.

These exceptions sent a message of what some have called Anglo-Protestant normativity, emphasizing the understanding that English was the singular language of the nation, just as Christianity was the singular religion. This idea was very much inculcated in people: in order to be American, you had to speak English, and you had to convert to Christianity.

But not everybody succumbed to that very particular, narrow vision of America. They found more spacious visions. At the Portland Assembly Center (formerly the International Livestock and Expo Center), Japanese Americans were put in stalls that had been occupied by livestock only a few weeks earlier. Still, they tried to make it livable. Even as the manure and the smell of urine lingered, they made it dignified. They did what they could to preserve their dignity and decency while living in these places where indignity was placed upon them.

In one photo I came across, a Buddhist priest’s daughter, Hiroko, is playing checkers with her friend, Lilian Hayashi. On the wall behind them is an image of the Buddha and a large American flag. Regardless of everything the government and the media were saying about Buddhism, this family was asserting that they could be both Buddhist and American at the same time. This is a very powerful thing: when they were faced with pressure, being told that they didn’t belong, they asserted their existence and insisted that they could belong and that their Buddhist and American identities could coexist.

They were going to build American Buddhism behind barbed wire, surrounded by armed guards, because that is how religious freedom is built.

And today, as we face messaging that our temples are not worthy of standing, that our elders deserve to be harassed, that our sacred objects need to be vandalized with Jesus-iconography, we can learn from the lessons these dharma ancestors have left for us. We can learn from these Japanese American Buddhists who made the point that they were going to build American Buddhism even if it wouldn’t be recognized by those around them. They were going to build American Buddhism behind barbed wire, surrounded by armed guards, because that is how religious freedom is built. That is how we can actually engage and enact the constitutional aspirations about freedom of faith.

People used what they could to persist and survive. At one of the high-security camps, a Soto Zen Buddhist priest wasn’t permitted to bring his prayer beads with him, so he collected peach pits—one a week—to make a new set. At Heart Mountain, some people found scrap wood at the mess hall and built beautiful altars so that their community could have a focal point to gather around in this moment of dislocation and loss.

In his Tenzo Kyōkun, or Instructions to the Cook, Zen Master Eihei Dogen lays out instructions for cooks in the monastery. He reminds them to take good inventory of the kitchen ingredients and to have the right heart when they cook. But his main teaching is to cook with what you have. Even if the ingredients are not that good, a good Zen cook should be able to make something of value.

With these instructions in mind, how can we take what we have and make something of value? How can we take the karmic and ancestral legacy that we all inherit and move forward from here?

People leaving a Buddhist church in winter at Manzanar concentration camp, California, 1943. Ansel Adams, Library of Congress #2002697859

We might look to Bishop Kyokujō Kubokawa, a senior Buddhist priest in the Jōdo sect in Hawai‘i. Like Bishop Kuchiba, he was picked up and arrested on December 7, 1941. He wasn’t even given a chance to return home to pack a suitcase or even grab a change of clothes. December 7 was a Sunday, so Kubokawa was arrested in his robes at the temple. In April of the following year, he was still wearing the same robes—robes he had worn for four months at that point. And he delivered a sermon during Hanamatsuri, the flower festival celebrating the Buddha’s birthday.

There is a classic image in many Buddhist traditions of a lotus flower blossoming above muddy waters. Often, it is used to represent the Buddha’s awakening: the lotus is the Buddha emerging above the saha world, the dusty world, the world of suffering. In his sermon, Kubokawa focused not on the lotus but on the mud. Pointing to his dusty robes, he said that this dirty world, this world of difficulty that they were immersed in, could be the exact ingredient to help them strengthen their Buddhist faith—to persist in these times so as to see a way out, to see the lotus flower beginning to bloom.

Even though he was stuck in these dirty robes behind barbed wire in an isolated internment camp, he shared that this was the most important Buddha’s birthday he had celebrated in his life—and the proudest moment he had had as a Buddhist priest.

Kubokawa teaches us that it is all about perspective. When we can’t see our way out, Buddhism can provide us with a glimpse through. This is the lesson of the lotus flower: the lotus cannot grow in sterile water. It needs the mud. The nutrients of the mud are what help it grow. In the same way, our freedom is interlinked with our karmic difficulties. We can transform our difficulties into something beautiful, awakened, and free. And we can do it together.

After their collective forced relocation, members of the Oakland Buddhist Church started a new Buddhist community in Topaz concentration camp. Delta, Utah, ca. 1943. Courtesy of the Terakawa Collection, Densho DDR-DENSHO-357-776

In their very survival and persistence against all odds, the Japanese American Buddhists of World War II have a lot to teach us about freedom. They were able to take what they had—the mud of the dusty world—and create something new, the beginnings of the American Buddhism we know today. And this creation was in service of the alleviation of suffering, something common to all Buddhists. As Buddhists, we are all trying to reduce suffering. We are trying to heal and repair our hurts that come down to us karmically. And the camp days can show us how to do that.

In Japanese ceramics, there’s a tradition of repair called kintsugi. Kin means gold, and tsugi means to join, or to repair. When you break something—let’s say your favorite teacup—instead of throwing it away, you use a lacquer resin to join the pieces and then dust it with gold. In the process of repairing the cup, instead of hiding the fact that it’s broken, you actually adorn it. You remember the breakage by adorning it with gold.

This offers a Buddhist way of thinking about reparations. The word reparations comes from the Christian tradition and originally emerged in the context of the French Catholic mass of reparation, which is an act of atonement for original sin. In a Christian context, Christ is the figure who will accomplish that restoration and reparation.

After their collective forced relocation, members of the Oakland Buddhist Church started a new Buddhist community in Topaz concentration camp. Delta, Utah, ca. 1943. Courtesy of the Terakawa Collection, Densho DDR-DENSHO-357-776

We often hear about America’s racial history in terms of original sin—that chattel slavery and the generations of dehumanization it brought about is America’s original sin. Martin Luther King, Jr. talked about this in terms of the promissory note of the Declaration of Independence: slavery a debt that needs to be repaid, or a sin that needs to be redeemed.

But because we Buddhists don’t believe in original sin and we don’t have a singular origin story of beginning, we can see these fissure lines and breakage lines of racial hurt and trauma and ask not how to forget them but how to remember them and even adorn them. The gold is not just about financial recompense but about proper reckoning about the dignity of human beings. For me, this is the style of repair that we might want to invoke as we grapple with the karmic legacies of our nation.

This work of repair is not just about one piece of legislation like H.R. 40, a commission introduced to begin current-day discussions of Black reparations in Congress. One piece of legislation is not going to fix everything. Because the problem has been multigenerational, the solution too must be multigenerational. It must transcend communities; it must transcend time.

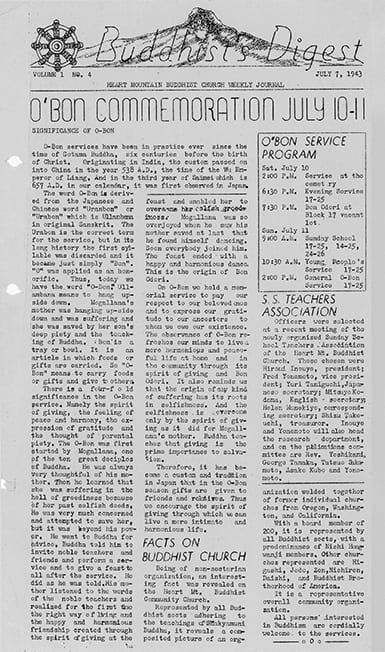

The Buddhist Digest detailed beliefs, practices, and other church matters. Heart Mountain Buddhist Church Weekly Journal, vol. 1, no. 4, July 7, 1943. National Archives #6922114

As an effort to do this work of repair, I’ve been working with an organization called Tsuru for Solidarity. The group was founded by Japanese American camp survivors from World War II and their descendants. They had experienced family separation, indefinite incarceration, and unjust deportation firsthand, so when they saw what was happening to families and children at the southern border in early 2019, they wanted to get involved.They traveled to the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas, where children and families were being detained, deported, and separated from one another. And they brought 10,000 tsuru, or folded paper cranes. One of the founders had made color photocopies of the cover of my book, American Sutra, and folded the copies into cranes to place on the fences. Because so few people spoke up for Japanese Americans back in World War II, these survivors and their ancestors decided to speak up for these children being separated from the families at the border. They placed these colorful cranes, folded with prayerful hands by so many Japanese Americans and allies, to make a statement of solidarity.

Once I joined Tsuru for Solidarity, I galvanized a group of Buddhist priests to get involved as well. We traveled to Oklahoma and partnered with Latinx Dreamer organizations like United We Dream to make a statement about how Buddhists must reckon with these enduring issues of displacement and anti-immigrant oppression.

We also began the work of mourning. We held ceremonies to remember George Floyd, placing his death in conversation with the death of Kanesaburo Oshima, who was shot in the back and killed in Fort Sill internment camp, the camp in Oklahoma where the Central American migrant children were going to be transferred. All of these histories are interlinked. And our sangha practice is a practice of encountering each other and seeing the ways in which we are connected to each other.

The Zen Buddhist teacher Hoitsu Suzuki once likened sangha to cleaning potatoes. He said that taking action together was like washing potatoes: “When people wash potatoes, instead of washing them one at a time, they put them all in a tub full of water. Then someone puts a stick in the tub and pushes it up and down, up and down. This makes the potatoes rub against each other; as they bump into each other, the hard crusty dirt falls off.” This process of encounter is not about purity. It’s not about isolation. It’s about becoming stronger and freer through rubbing against one another and noticing our interlinked natures.

How do we heal together, and how do we have faith that our lives are inter-connected in deep, moral ways and that our liberation is interlinked?

Also from the Zen tradition, Guoan Shiyuan (Jpn., Kakuan Shien) described the three pillars of Buddhist practice: great doubt, great faith, and great determination. These three pillars can be a guide to us in the work of racial justice and healing. Great doubt is a process of questioning and probing deeper, going beyond easy or simple answers. In the context of race in America, we have to move beyond the Black-White binary as the sole framework for talking about race. It can be tempting to fall into dualistic thinking, but we have to go deeper and see the full complexity at play. We not only have to demand justice for Black Americans, we have to ask about repairing the karma of our nation’s racial harms for Indigenous people, for Latinx people, for Asian people, and for everyone in between.

Great faith asks us to turn toward our own Buddha nature. How do we heal together, and how do we have faith that our lives are interconnected in deep, moral ways and that our liberation is interlinked? Our healing doesn’t have to be rooted in original sin.

The legendary founder of the Zen lineage, Bodhidharma, is attributed with the saying: Nana korobi, ya oki, “Seven times falling down, eight times get up.” This path of reparations and racial healing will take many tries. There are so many issues we’re up against. We’re going to fall down many times. And if we fall down a million times, we have to get up a million and one times. That’s great determination.

Notes:

- Nyogen Senzaki, “Leaving Santa Anita,” in Eloquent Silence: Nyogen Senzaki’s Gateless Gate and Other Previously Unpublished Teachings and Letters, ed. Roko Sherry Chayat (Wisdom Publications, 2008), 12.

- Translated in Noriko Shimada, “Social Cultural, and Spiritual Struggles of the Japanese in Hawai‘i: The Case of Okumura Takie and Imamura Yemyo and Americanzation,” in Hawai‘i at the Crossroads of the US and Japan before the Pacific War, ed. Jon Thares Davidann (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2008), 161.

Duncan Ryūken Williams, MDiv ’93, PhD ’00, is chair of the School of Religion, Professor of Religion, and Professor of American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California and the director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture. He is a Buddhist priest and author of American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War (Harvard University Press, 2019) and The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Soto Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan (Princeton University Press, 2005).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.