Featured

Secular Death

Can difficult writing help us grapple with difficult loss?

Starting from nothing with nothing when everything else has been said

—Susan Howe, That This1

This single, unpunctuated line is the second paragraph of Susan Howe’s That This, a book-length poem dedicated to the memory of her third husband, the philosopher Peter H. Hare. She has just described her discovery of his dead body: “I knew when I saw him with the CPAP mask over his mouth and nose and heard the whooshing sound of air blowing air that he wasn’t asleep. No” (11). Howe juxtaposes her refusal—“No.”—with Sarah Pierpont Edwards’s letter of July 3, 1758, announcing the death of her husband, Jonathan Edwards, to one of their daughters.

“Oh that we may kiss the rod and lay our hands on our mouths! The Lord has done it. He has made me adore his goodness, that we had him so long. But my God lives; and he has my heart. . . . We are all given to God: and there I am, and love to be.”

“I admire,” Howe writes, “the way thought contradicts feeling in Sarah’s furiously calm letter” (12–13).

The furiously calm contradictions of Sarah Edwards’s letter find their justifying source in the anguished Psalm to which her words likely allude. Psalm 2 opens with a question: “Why do the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing?” The answer, in the King James Version, defies summation. Reading the Psalm, I am not always sure who is speaking to whom, but there is no doubt as to what is being promised:

Ask of me, and I shall give thee the heathen for thine inheritance, and the uttermost parts of the earth for thy possession.

Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron; thou shalt dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel.

Be wise now therefore, O ye kings: be instructed, ye judges of the earth.

Serve the LORD WITH FEAR, AND REJOICE WITH TREMBLING.

Kiss the Son, lest he be angry, and ye perish from the way, when his wrath is kindled but a little. Blessed are all they that put their trust in him. (Psalm 2:8–12)

This is difficult writing: the rage and the violence seem directed—everywhere. Sarah Edwards feels this rage and this violence. She feels it directed against her husband and against herself and against her daughter, but she also, with ease, identifies the rod—which will “dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel”—with the Son, and so with the promise of blessedness.

For Sarah Edwards, the one who destroys is also the one who saves. Howe sees this clearly:

For Sarah all works of God are a kind of language or voice to instruct us in things pertaining to calling and confusion. I love to read her husband’s analogies, metaphors, and similes.

For Jonathan and Sarah all rivers run into the sea yet the sea is not full, so in general there is always progress as in the revolution of a wheel and each soul comes upon the call of God in his word. (12)

Scripture calls and gives a calling to Jonathan and Sarah Edwards. It calls them to God where, Sarah writes, “I love to be.” Howe sees this in Jonathan and Sarah Edwards, but she doesn’t experience it: “I read words but don’t hear God in them” (12). Howe loves Jonathan Edwards’s analogies, metaphors, and similes, most of them biblically based, but she hears in these words “the unpresentable violence of a double negative” (13). The rod, perhaps, without the Son? Or more troubling still, the rod and the Son without any promised salvation? For Howe, what is crucial is how unpresentable this is.

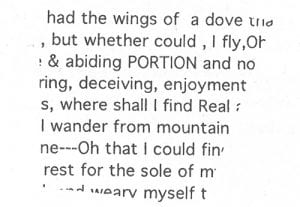

That This goes on to perform that unpresentable violence in often illegible textual collages, strips of words and fragments of words cut from the writings of the Edwards family and other, unspecified texts, placed seemingly at random on the page. The Psalms appear again on page 47, in a more hopeful light, although one that remains tethered to Howe’s framing question: “where shall I find Real:”

“Maybe,” Howe writes, “there is some not yet understood return to people we have loved and lost. I need to imagine the possibility even if I don’t believe it” (17). These poems mark the impossible necessity of imagination; Howe returns to her husband—she returns to the Edwards family—through these barely legible textual collages. Her reading—of her husband’s autopsy report, his emails, the detritus that catches her eye as she wrestles with the reality of his death, the paintings of Poussin and the art historian T. J. Clarke’s reflections on those paintings—and what she makes of them in her writing are the return:

This sixth sense of another reality even in simplest objects is what poets set out to show but cannot once and for all.

If there is an afterlife, then we still might: if not, not. (34)

This is the background against which I want to talk about how we die now, those of us who are no longer Christian. I am interested in how we approach the difficulty of death, our own and that of others, and how difficult literature, writing it and reading it, might be a training ground for approaching the difficulties of death—and of life. I will speak in terms of what Michael Warner calls “ethical secularism,” a version of secularism which asks how we live now, those of us for whom religious practices are no longer formative. In Warner’s words, “It presents itself as a project for becoming the kind of person who can rightly recognize the conditions of existence, and although it is an attempt to overcome Christianity it does not secure its stance as a privileged default against the particularities of religion.”2 I’d like to say that I don’t wish to overcome Christianity. I’d like to say that death demands particularity. But for me, as for many others, Christianity is simply—but there is nothing simple about it—gone.

When I think about religion and what we grandiosely call literature, I am less interested in the exploration of religious themes or images than in the analogies and disanalogies between literary practices and religious practices of writing and reading. The practices of religious elites—and increasingly not only elites—in Western Christianity circled endlessly around the Psalms, with reading, recitation, song, and meditation leading to the production of new songs in and through engagement with the biblical text. In medieval monastic life, monks and nuns, either individually or in community, enact the continual praise of God that is heaven itself through their recitation or singing of the Psalms. For John Cassian, a key figure in the development and theorization of Christian monasticism in the Latin West, the techniques of repetition central to the monastic life are not at odds with, but themselves produce, spontaneity.

Dying and dead monks and nuns are surrounded by their communities, who recite or sing the Psalter over them. By the High and the late Middle Ages, these practices have moved out of the confines of the monastery. The beguines, semireligious women living lives dedicated to God and Christian perfection in the world, were often employed to care for the sick and the dying. This included reciting or singing the Psalms over them, perhaps at times with them. (Did they sing in Latin? The French, Flemish, German, Italian, English vernaculars? Many of the dying may not have understood the words of the song.)

Those raised within Christian and Jewish traditions often forget how difficult the Psalms are—not just formally, but also in their vivid and incredibly complex imagery, in the harshness of the world and the God they depict, in the truths they purport to tell. For early theologians, theorists of the Psalms and literary critics all, and often poets, the Psalms are at the heart of the Christian life because they contain the entire range of human emotion. Through uttering the words of the Psalms and looking from the book of scripture to what Bernard of Clairvaux calls the book of experience, moving back and forth between the two so that the words of the Psalmist become one’s own and emerge, spontaneously, from one’s lips, Christians come to understand who they are, who God is, how they stand, individually and communally, before, with, and in that God.

The Psalms are not my scripture. But since I was a small child I have read religiously; perhaps I have even begun to write that way. And that is what I see, vividly, complexly, difficultly, in the work I love. An (a)typical juxtaposition, from Fanny Howe’s (Susan Howe’s sister) Tis of Thee, chosen (almost) at random (X: African American Man; Y: European American Woman; Z: Their grown son):

X: and Z:

Any discussion of race is really a discussion about the creation of the universe.Y:

Now I believe that when the Messiah comes the world will have no images,

since the image will be cut free

from the object, released like beef from a cow,

and competition will automatically founder

as an instinct, having no visible object in sight.

Then on that day I won’t have to look for you in order to know you. (60–61)3

I don’t believe in the messiah, but I believe in Fanny and Susan Howe. What does that make me?

♦♦♦

I have a fantasy, that when I am dying, someone will read to me the opening pages of The Portrait of a Lady.

Under certain circumstances there are few hours in life more agreeable than the hour dedicated to the ceremony known as afternoon tea. There are circumstances in which, whether you partake of the tea or not—some people of course never do—the situation is itself delightful. Those that I have in mind in beginning to unfold this simple history offered an admirable setting to an innocent pastime. . . . Part of the afternoon had waned, but much of it was left, and what was left was of the finest and rarest quality. Real dusk would not arrive for some hours; but the flood of summer light had begun to ebb, the air had grown mellow, the shadows were long upon the smooth, dense turf. They lengthened slowly, however, and the scene expressed that sense of leisure still to come which is perhaps the chief source of one’s enjoyment of such a scene at such an hour. From five o’clock to eight is on certain occasions a little eternity; but on such an occasion as this the interval could be only an eternity of pleasure.

There are three men on the lawn in Henry James’s not so very innocent scene, an old man and two considerably younger—a father, a son, the son’s friend. (And two dogs, a collie and a “bristling, bustling terrior” who only later, in passing, we will find to be named Bunchy. All of the names come later.)

Daniel Touchett and his son Ralph are both dying.

Their history, and that of the young woman who comes to join them, may seem simple, even banal. How can one speak of eternity with respect to an afternoon tea? (A little eternity and hence no eternity at all; and yet, beyond the irony and the boredom, on this occasion “an eternity of pleasure.”)

I found myself thinking about this scene in James and about my own imaginary deathbed scene, during which I am remembering James or listening to some unspecified person reading James to me, while reading David Orr’s Beautiful & Pointless.4 Orr wants to argue against the notion that poetry needs to be something grand, dealing with the sublime and the eternal, in order to be interesting and worth spending one’s time on. Poetry, he writes “seems beautifully pointless, or pointlessly beautiful, depending on your level of optimism” (187). (An afternoon tea on a beautiful lawn dipping down to the Thames. James refuses to leave its beauty alone.)

Orr’s line marks the end of a section; a new one begins, the penultimate one of the book.

My father died of cancer in March of 2007, as I was beginning work on this book. He was sixty-one. It’s difficult to type those sentences for many reasons, not least among them the fact that I’ve been a book critic for over a decade now, and almost always find myself cringing during the inevitable fetch-me-a-tissue moment in any personal essay or memoir. Still, throughout this book . . . I’ve tried to suggest what a relationship with poetry actually looks like. . . . I’d be falling short if I didn’t try to offer some sense of what—for me—poetry has proven it can and cannot give. Sad as it may be, we often discover the true contours of any relationship in the situations that matter most to us; and sadder still, those situations tend to be ones in which something we love is lost, or in danger of being lost. So pull out your tissues, and let’s talk about it. (187–88)

(I’ve got a lot of these stories. My father, dead at sixty-five, when I was twenty-three. My oldest brother and mother dead nine years later, in Pedro’s case almost to the day of my father’s death. My mother four days later. My brother Michael died in 2013 on the same date as Pedro. Between them, a sister and another brother, my best brother, Daniel. And that’s not all.)

(I could give a shit about tissues.)

“Cancer,” Orr writes, “can kill you in many ways” (188). His father had a stroke in the midst of (and likely caused by) chemotherapy. The stroke left Orr’s father partially paralyzed and unable to shift the pace, intonation, or stress of his words. Suffering from what is sometimes called “flat affect” (surely a misnomer—the voice is flat, but is the affect? perhaps it’s just easier to think that what we can’t hear isn’t there), his father couldn’t “slow down and modulate his voice.” A speech therapist gave him various exercises meant to help.

(Cancer can suffocate you; rot you from the inside out or from the outside in; make you hurt so badly you can’t even scream. It can give you a heart attack or tangle your guts so that you heave your own shit. No one wants to know all the ways that cancer can kill you.)

As Orr self-deprecatingly explains, the not unself-interested thought occurred to him that poetry might also help his father. It deals, often, with—or perhaps better in—the stress of meter, the intonations engendered by rhythm and rhyme, the pacing needed to articulate assonances and alliterations. He searched his parents’ house for leftover books from college and, “flush with inspiration,” returned to his father “armed with the fruits of English poesy.” He tells us he learned one lesson very quickly:

Do not attempt to get a stroke victum to read Hopkins. “I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-/dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon . . .” I can barely pronounce this myself, and I have full use of my tongue. We did a little better with Robert Frost. (190)

(I gave my father The Complete Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins for Christmas a year or two before he died.) (He’d had an old, mottled edition, its wartime paper disintegrating under my hand as I tried to read it. Whose gift was this?)

Orr and his father read from Frost’s “The Silken Tent”; Orr cites the opening four lines of the poem.

She is as in a field a silken tent

At midday when the sunny summer breeze

Has dried the dew and all its ropes relent,

So that in guys it gently sways at ease . . .

Orr reflects on what he loves in the poem; its technical virtuosity—the entire poem is one sentence—and what he calls “the delicate exactness of the first line.” “ ‘She is as in a field a silken tent,’ rather than, for instance, ‘She is like a silken tent in a field.’ ” For Orr, following the critic Robert Pack, “ ‘the metaphor of the tent does not merely describe the ‘she’ of the poem, but rather the relationship between the speaker and the woman observed’ ” (191). (I am not at all sure that this is right.) What Orr likes about it is that Frost, in giving a relation—the metaphor itself—about a relation does something “more unusual and difficult” than poets normally attempt. (All the power in these relations, all the wealth in James’s lawn, will have to remain unanalyzed. Not by James, who can’t stop analyzing, but by Orr.)

Orr admits, though, that none of this meant anything to his father. Or perhaps better, he assumes, on the basis of what his father says to him about the poem, that its technical virtuosity meant nothing to him. For his father, the tent was interesting. It reminded him of tents pitched in open fields by traveling circuses, a sight he recalled from his own childhood. For Orr, though, the pleasure his father found in the poem wasn’t adequate. He writes, “if reminscence was all that was needed, we could just as easily have been reading a magazine article about P. T. Barnum” (192). He worries that what is properly poetic about Frost’s lines is not a part of his father’s enjoyment—the sound of the poem, its syntax, “the expert maneuvering that Frost does in order to unload the poem’s only four-syllable word in the poem’s penultimate line: ‘In the capriciousness of summer air.’ ” Orr wanted his father to hear that—and to have it “help somehow.” But help with what? Orr doesn’t tell us if the meter and rhythm of the poem made his father better able to bring intonation to his speech. That was, I thought, the point of the exercise. Given that Orr doesn’t tell us whether reciting the poem helped his father’s speech, I am going to assume that what served as the justification for the exercise was not its real agenda.

(Why can’t a magazine article about P. T. Barnum be a poem?)

Instead of telling us about his father’s voice, Orr tells us about his father’s reminiscences. And the circus, clearly, isn’t sufficiently profound, not least because it doesn’t seem to require poetic form for its elicitation. But is the clever use of syntax and metaphor in itself valuable? Should his father be taking the same pleasure in the poem that

Orr takes, and without that specific technical pleasure, is the poem a waste of time? Does poetry require formal difficulty—in its execution and in our appreciation of that execution—in order to be worthwhile? And do we have to be able to recognize, analyze, and describe these technical achievements in order to take pleasure in them?

And then there is the question of meaning. Frost’s poem isn’t that hard to understand—arguably, its technical virtuosity is hidden by the relative simplicity of its meaning. Some readers of poetry, those who love secrets, might scoff at its lucidity. But there are secrets, and there are secrets.

Does Orr suppose his readers know the poem? That they will go look it up? (Or is he hoping that they won’t?)

Anyway, I did.

(On the flyleaf of my copy of The Complete Poems of Robert Frost [1930; second printing 1949] “For Jimmie/21 Dec’50/Joe.” From my dad to my mom, on her twenty-ninth birthday. There is a Sunday “Peanuts featuring ‘Good ol’ Charlie Brown” folded into fourths and tucked neatly into the front cover of the book. “Sally! Your beach ball is floating away. It’s going clear across the lake!” “Stay calm, big brother . . . stay calm!” She addresses the ball. “Okay, you stupid beach ball, come back here right now, or I’ll see to it that you regret it for the rest of your life!” The ball returns. “You have to know how to talk to a beach ball!” says Sally. Who thought this was so funny they needed to save it? What did it mean to them? There is a golf joke in there somewhere. And my brother Daniel.)

Okay, sorry, the poem.

She is as in a field a silken tent

At midday when a sunny summer breeze

Has dried the dew and all its ropes relent,

So that in guys it gently sways at ease,

And its supporting central cedar pole,

That is its pinnacle to heavenward

And signifies the sureness of the soul,

Seems to owe naught to any single cord,

But strictly held by none, is loosely bound

By countless silken ties of love and thought

To everything on earth the compass round,

And only by one’s going slightly taut,

In the capriciousness of summer air

Is of the slightest bondage made aware. (443)

The “central cedar pole” that is the “pinnacle” of the tent, “to heavenward” “signifies the sureness of the soul,” of her soul. When no particular string pulls, the pole and its tent seem free (although Frost does not use the word), despite that—in fact because—it is “loosely bound / By countless silken ties of love and thought / To everything on earth the compass round.” The more plentiful our ties, the more sure—the more upright and capacious—the soul. But when one pulls—the speaker of the poem? a chance summer breeze?—only then is it (but of course, the tent isn’t aware, only “she” is), only then is she made aware of its/her bondage, however slight.

(After my brother Daniel died, my sister had a dream. She was late for church, standing in the back looking to see if she could find a seat. Daniel was there, in a full pew, with his daughters and me and my other brothers and my other sister and my sister’s kids. Far too many for one pew. (When we were kids we could squeeze six, but that still meant two pews for the whole family. And endless fights over who had to sit with my mother.) Daniel gestured to my sister to come and sit in the pew anyway. She did and we were all there and there was more than enough room for everybody. That was my brother’s heart.)

There is more in Frost’s poem than might immediately catch one’s eye.

(As my father lay dying, I read Tertullian’s On the Resurrection of the Flesh. My father’s edemic leg hung outside the bed clothes—my always so composed, so elegant, so immaculate father’s body cast into disarray by pain and disease. My father, who, dead drunk, passed out with a cigarette so carefully balanced between the fingers of his right hand as it lay, folded gently on his left, across his chest, that only a perfect column of ash was left, hours later, when I found him, afraid to move the stub lest the ash scatter over his unburnt hand or shirt or the white sheet on which he lay.

My father, who, his leg run over, twice, by a drunken friend, got up, walked to the driver’s side, and took the wheel.

My father, who caught me when I fell, blood running down his bright white shirt.

His swollen leg and foot fell out of the bed clothes. I wanted to grab hold and pull him back into this oh-so-painful-flesh.)

“[P]oetry,” Orr concludes, “needs a history with its readers.” For Orr, poetry, to be useful, or helpful, or whatever it is he’s seeking

needs to have been read, and thought about, and excessively praised, and excessively scorned, and quoted in melodramatic fashion, and misremembered at dinner parties. It needs, in a particular and occasionally ridiculous way, to have been loved. If poetry could do nothing for my father that a thousand other things couldn’t do, that was because it hadn’t been a part of his life—just as when I’m eventually laid low, I will take little comfort in cello concertos and origami. (192)

(So does a Christian need to have spent her life reciting the Psalms, being shaped by the poems’ sound and their content, by the work monks and nuns do with and to them, in order for their recitation as she dies to be “helpful”? Why then sing Psalms over the beds of the dying, even those of the laity who may not have been particularly devout—although the Psalms were everywhere, and so everywhere heard, in the Middle Ages?)

(A friend lay with his eyes closed as the church choir sang around his bed. But what he seemed most to enjoy, or so I like to imagine, were the tidbits from a biography of Louis Zukofsky I was reading as we sat together in the late spring sun. He lay, with tubes attempting to stem the flow of waste that otherwise would come, periodically, from his mouth.)

What Orr’s father loved and enjoyed for a few of his dying days was Edward Lear’s “The Owl and the Pussycat.” (My friend loved this poem too, its divine foolishness.)

The Owl and the Pussycat went to sea

In a beautiful pea green boat,

They took some honey, and plenty of money,

Wrapped up in a five pound note.

Lear’s nonsense poem gave Orr’s father intense delight for a number of difficult weeks before the most difficult ones that led to his death. Orr assumes that his father must have been familiar with the poem, or one like it, and that the pleasure he took in it is tied to some dim memory of reading to his children many years before. “It was,” Orr writes, “happy silliness, soon to end—and surely there were a hundred other things that might have given my father the same comfort—but this absurd poem was, in its own small way, something.” Orr cites the closing lines of the poem and his father’s response to them:

“Dear pig, are you willing to sell for one shilling

Your ring?” Said the Piggy, “I will.”

So they took it away, and were married next day

By the Turkey who lives on the hill.

They dined on mince, and slices of quince,

Which they ate with a runcible spoon;

And hand in hand, on the edge of the sand,

They danced by the light of the moon,

The moon,

The moon,

They danced by the light of the moon.“I really like,” said Dad, “the runcible spoon.” Reader, there are worse things to like. Or to love. (194)

In Infinite Jest, a novel I’ve never read, David Foster Wallace has his character, Rémy Marathe, a Québecois terrorist, say, “Choose with care. You are what you love. No?” Truth or truism, this is just the sort of literary pronouncement David Orr finds deeply embarrassing. So do I, a lot of the time; when writers proclaim that poetry and fiction can radicalize consciousness, transform the political sphere, recreate the everyday world, provide the sole and necessary grounds for ethics, usher us into an easeful death—I cringe. Poetry and fiction are marks on the page and sounds. And death, like literature, is difficult.

(When my father and mother, my brothers and sister and friends died, I wanted to read difficult books. Really really difficult. Only the incomprehensible is comforting in the face of how hard death is.)

Who knows why Orr’s father liked Lear better than Frost, although I have a feeling it has less to do with prior knowledge of the poem than with its ability to help him articulate sound and with it, perhaps, feeling—feelings of whimsy and humor. (My sister was in a fever as she died. “Better get used to it,” someone said. We laughed and laughed. My sister, I fear, was unconscious.) Sounds elicit whole worlds of feeling. They are among the strongest—and arguably the last—of the strings that hold us to earth and enable us to reach . . . heavenward? (My sister and I sang to Daniel, snatches of half-remembered songs, as he gasped out his last, morphine-slowed breaths.) A novel by Henry James or David Foster Wallace, a poem by Robert Frost or Edward Lear, a piano concerto or a Dum Dum Girls song, it’s the saying, the listening, the reading, the repetition, the way something we love pulls us back to earth even as it lets us fly—that’s what I love.

(In my (day)dreams, it’s what I am.)

(In my (day)dreams, difficulty’s reverberations sustain and shake and never simply soothe.)

♦♦♦

Someone close to me said that he doesn’t care what goes on at his funeral, except that he wants loud music. Really really loud.

What’s the aging hipster’s version of the Psalms?

Oh it’s a game, hold tight

Can you shut your eyes?

Shut out the light

Death is so brightFrom dreams you wake to shock

To find it’s true

But she’s not you

No she’s not youAnd you’d do anything to bring her back

Yes you’d do anything to bring her backOh I wish it wasn’t true

But there’s nothing I can do

Except hold your hand

’Til the very end

’Til the very end.

—Dum Dum Girls, “Hold Your Hand”

The words are good, but it’s the wall of sound, the layers of feedback, the echoing resonating chaos of it all, that bring the house down.

Notes:

- Susan Howe, That This (New Directions, 2010).

- “Rethinking Secularism: Was Antebellum America Secular?” posted by Michael Warner on The Immananet Frame: Secularism, Religion, and the Public Sphere, www.ssrc.org.

- Fanny Howe, Tis of Thee (Atelos, 2003).

- David Orr, Beautiful & Pointless: A Guide to Modern Poetry (HarperCollins, 2011).

Amy Hollywood is the Elizabeth H. Monrad Professor of Christian Studies at Harvard Divinity School. Her most recent book is Acute Melancholia and Other Essays (Columbia University Press, 2016). This essay is adapted from presentations she delivered at Duke University and Drake University in February 2015 and March 2016.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.