In Review

Recalled to Life

By Davíd Carrasco

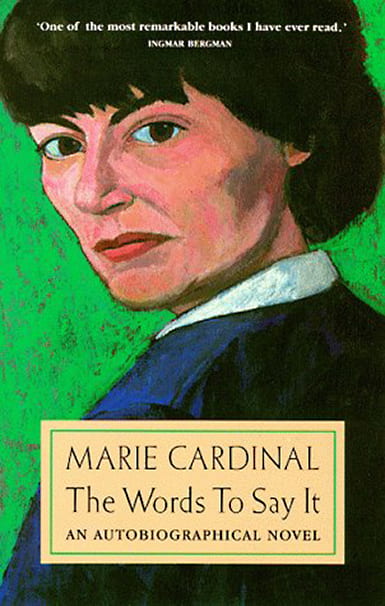

When Marie Cardinal’s The Words to Say It first appeared in English 22 years ago, it caused profound admiration, shock, and stir among its readers. It was called “fascinating” (Toni Morrison), “gorgeous” (The New York Times Book Review), “one of the most remarkable books I have ever read” (Ingmar Bergman), “as near as perfect as a novel can be” (Bruno Bettelheim), and “in the category of the most significant works of feminist literature” (Frankfurter Rundschau). Yet it appeared in the United States almost by accident. After its initial appearance in 1975 in France, where it won the Prix Littré, selling more than 2 million copies in Europe, it was rejected for publication by all American publishers save one—the small but wise publishing house Van Vactor & Goodheart, which finally translated it and brought it to life for a larger number of United States readers, who discovered a unique story of suffering, courage, terror, and healing.

In the two decades since, The Words to Say It (Les mots pour le dire in the original French) has gained profound respect and a growing audience, especially among psychoanalysts, novelists, biographers, college professors, feminists, literary critics, and students. During these years, I have been teaching this book in my history of religions courses, where it has helped my students awaken to new understandings of women’s voices, the evocative powers of dreams, the search for the soul, and the creative and destructive forces in human families. When Pat Goodheart, the skilled translator of the book, asked me to write a new introduction to this masterpiece, I turned to my students for comment.

The Words to Say It

“You must warn the readers that The Words to Say It is a female horror story, a world of fear and the grotesque,” one female student advised me. Another woman quickly added, “But tell them also that it’s a love story on several levels.” These challenging views of Marie Cardinal’s unsparing account of her descent into madness and her courageous recovery through seven years of psychoanalysis in Paris have been repeated again and again by my students. This duality of horror and love appear in two pivotal moments in Cardinal’s autobiographical novel. The first moment appears immediately after her first psychoanalytic session, during which she is stunned into an awareness that her unending menstrual bleeding, in fact her entire existence, is in the grip of an inward monstrosity she calls the Thing. She draws on religious imagery to communicate her ambivalence about this inner pandemonium:

That evening it was apparent to me that the Thing was the essential element: it was all powerful.

I was made to face the Thing. It was no longer so vague, although I didn’t know how to define it. That evening I under-stood that I was the madwoman. She made me afraid because she carried the Thing inside. She at once disgusted and attracted me, like those magnificent reliquaries in a religious procession enclosing the remains of a saint. . . . The lamentation and the ecstasy. . . .

The image is of a double person who is trapped and engorged with a mysterious outrage. But a very different person emerges by the end of the book, a woman with hope for an expanding, constructive life. Cardinal is tinged with ecstasy as she leaves her doctor’s office for the last time: “The door closes behind me. In front of me, the cul-de-sac, the city, the country and an appetite for life and for building as big as the earth itself.”

What takes place between these two moments in The Words to Say It is the story of what it feels like to be inside the arduous process of psychoanalysis. We witness, sometimes with the hair standing up on our necks, sometimes holding our breath, and sometimes with tears, how the author was able to struggle courageously, with the aid of her doctor, to uncover the secret sources and powers of her madness and to make decisive changes in her behavior and thinking. Many people have undergone this journey through psychoanalysis, but no one has written about it with the sway, power, and clarity of Marie Cardinal.

Her narrative achievement goes against Cardinal’s own assertion that analysis “can’t be written down.” She says it would take “thousands of pages, many of them repetitious,” filled with “emptiness . . . deadness . . . slowness . . . vagueness . . . this immense monotony” interrupted only occasionally by “several strokes of lightning, those luminous seconds during which the entire truth appears . . . radiant splendor of the truth. And so it goes.” She is correct that it is impossible to put the complex rhythms and mutual work of any psychoanalysis to paper, but Cardinal—who died in May 2001 at age 72—has come closer than anyone else I have read to finding the words to bring the dynamic experience of psychoanalysis to life. Through her gifts and strategies as a novelist, she gave us a literary revelation of a search for one’s lost soul.

My appreciation for her achievements in psychoanalysis and in writing about it comes from the many ways this book entered, and has reentered, my life: among them, through teaching the book with an emphasis on its many religious dimensions, and during a fateful meeting with Toni Morrison.

‘Shareable Language’

In 1991, I was a visiting professor at Princeton University in the department of religion and I heard a series of Toni Morrison lectures on the ways black people ignite critical moments of discovery in American literature. One lecture was on the powers of blackness and whiteness in Herman Melville’s novels. I was moved by Morrison’s direct and daring words about a process she called “entering what one is estranged from” from a background she dubbed the “corners of conscious-ness” in the racial history of the Americas. Afterward, I spoke with Morrison and told her that among the associations her lecture stirred in me was a memory of a wonderful book of a woman’s therapeutic journey into her unconscious, Marie Cardinal’s The Words to Say It. This disclosure surprised Morrison and she said something to the effect: “That is remarkable. I actually got part of the idea for this series of lectures from reading that very book.” This encounter taught me something new about the power of Cardinal’s vision and writing, namely, that Cardinal’s life story and account of psychoanalysis, traditionally thought to be useful to analysts, feminists, and literary scholars, not only appealed to a historian of religions like me, but was capable of igniting critical thinking and creative writing about the agonies of race in America in one of our greatest writers. Not long after our first meeting, Morrison wrote these words about the “shareable language” in Cardinal’s work in the opening pages of Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination:

Cardinal’s project was not fiction, however; it was to document her madness, her therapy and the complicated process of healing in language as exact and as evocative as possible in order to make both her experience and her understanding of it accessible to a stranger. . . .

It is a fascinating book and, although I was skeptical at first of its classification as “autobiographical novel,” the accuracy of the label quickly becomes apparent. It is shaped quite as novels most frequently are with scenes and dialogues selectively ordered and situated to satisfy conventional narrative expectations. There are flashbacks, well-placed descriptive passages, carefully paced action, and timely discoveries. Clearly her preoccupations, her strategies, and her efforts to make chaos coherent are familiar to novelists.

Morrison helped to reinforce the deep appreciation I already felt for this book. Marie Cardinal’s book would end up not only being a long-term ally for my own “bringing forth,” but would prove to be an invaluable text in my teaching. A single early exchange in the book proved invaluable in helping me and my students understand how psychoanalysis was mutual work in search of the human soul.

After escaping from a sanatorium and a regimen of pills designed to subdue her into an operation for the extraction of her uterus, Marie Cardinal arrives at a psycho-analyst’s office in a state of desperation and madness. She recites for him a story of hallucinations and of her endless menstruations that have driven her, step by step, into increased isolation and insanity, as she checks for her blood on buses and bathroom floors. She watches to see if the psychoanalyst is rattled. Perhaps she wants to astonish him with her pitiful condition. She notices how quietly and intensely he listens to her “ferocity.” In the brief initial exchange between them, he transmits two messages to her. The first message is simply that he is willing to try and help her. The second is that she has a potential to help herself by finding a new language, her own language, with which to define and change her life. He tells her, “You were right not to take those pills. . . . I think I can help you.” And, he says:

There is one thing I want to ask you, however: try not to pay attention to what you know of psychoanalysis; try to avoid any reference to this knowledge; find equivalents for the words in the psychoanalytic vocabulary which you have learned. Everything you know can only hold you back.

This invitation, not to ingest pills or to imitate the clinical language of therapy, but to discover her own words, stirs in Cardinal the hope of “a path between myself and another.” “If only it were true,” she writes. “If only I could talk to someone who would really listen to me.”

What is revealed to the reader in the early, tense, and crucial meetings between Marie Cardinal and her analyst is that psychoanalytic work is meant to be mutual work primarily for the benefit of the patient in search of the soul, a new internal life. This mutual search for a new life is affirmed in Cardinal’s dedication at the start of the book, which reads, “To the Doctor who helped me be born.” Cardinal does not claim that the doctor gave her birth. Nor does she imply that she gave birth to herself. She is not saying she went through a “rebirthing.” Rather, her new life, symbolized in the writing and publication of this marvelous book, is the creation of a shared labor between herself and her analyst.

The Religious Dimensions

In spite of the clearly religiously tinged words Cardinal uses to describe her experience of psychoanalysis, including rebirth and new life, I discovered in teaching the book that the critical literature on The Words to Say It has been focused by three kinds of lenses: the feminist, the psychoanalytic, and the literary. These approaches have helped us understand a good deal about Cardinal’s book, but it is remark-able that Cardinal’s interlocutors almost completely ignore the religious dimensions of the book and her life story. Her story pulses with religious practices and symbols and is animated by ritual imagery that is both Catholic and psychoanalytic in style and meaning. The work is organized by a journey she calls her “expeditions into the unconscious,” and it reads like a pilgrimage along a dangerous labyrinth toward the center of her soul. While psychoanalysis has tended to present itself as a critic of religion rather than as a practice that can engender experiences of a religious cast, Marie Cardinal’s narrative demonstrates just how much her analytic experience had in common with certain religious practices and meanings. By exploring the religiosity of her psychoanalysis, my students and I have discovered areas of significance in her words, feelings, and relationships that have been overlooked.

There are two religious styles represented in the book. One is the traditional religious style of Roman Catholic practices of church and liturgy. Catholic rites at sacred times and sites formed Cardinal’s sense of self and family, such as religious training in a convent school, repeated visits to graveyards, and Holy Communion in church. Her days and nights were filled with stories of miracles, an array of rosaries, and crosses on walls. She internalizes a theological description of her world from visits to the confessional, in sermons, and in her mother’s teachings about God, the female body, sex, family, and, especially, “the relics of my dead sister” that her mother would fondle on some nights. This theological dimension has a deep impact on her identity as a girl and her ties to her mother and in the formation of her illness. While she was not a pious child, she admits that there was emotional power in these traditions.

In fact, the only time I came to have a religious attitude was in moments of ecstasy created by objects or anecdotes. Something very concrete. Stories of miracles . . . made me dream. I really loved Jesus.

The second religious style involves her long, courageous search for experiences, insights, and values that transcend her illness and family agony. I call this the “search for the soul.” By soul I mean the deepest, highest, and most valuable parts of our lives which are always hidden from us, to varying degrees, but which contain our most profound longings, as well as some keys to our true identity and our capacities to do harm or good to others and ourselves. This religious style, in her case, has little to do with Cardinal’s traditional Catholic religion, and even counters it in some ways. It can be deciphered, in part, by employing other disciplines, combined with the insights gained from religious studies and its attention to sacred places, numinous emotions, rites of passages, and pilgrimages to the “center of the world,” and the power of words to shape our experiences and relationships.

For example, Cardinal struggles with a sense of her “evil nature” and seeks to be liberated from this evil through a search for its origins. The struggle for liberation from “the Thing” is similar to a thirst for liberation and transcendence that ap-pears in the religious literature of many societies. However, the “transcendence” that she seeks and finds is not symbolized or embodied in a celestial or terrestrial god or heaven in the sky. Rather, it is experienced in feelings of release, some gradual and some abrupt, from the hauntings of her past, the specters of violent and humiliating family events that have tormented her mind with fear and squeezed the blood from her womb on a nonstop schedule. Cardinal slowly constructs a new vision of how she can live in caring and creative relationships with her husband, her children, and her own ability to write.

Through working with both of the religious styles mentioned above, my students have comprehended some of the complexity and depth in the relationship between her horror story and her love story. It must be said that because it is so extraordinarily troubled and intense, Marie Cardinal’s story is not paradigmatic of what most people take into psychoanalysis or what they find revealed there. Yet many of my students, especially women, have felt a strong empathy with events in Cardinal’s life and identified with the power and intensity of her feelings toward her parents and her body, her attitude toward God and the church, and her work toward healing. The tale of her discoveries pulled back membranes of comfort and denial from their own lives, repelling some readers but drawing others deep into her sessions on the couch. Our reflections on her accounts of these sessions have led us to view her struggles in terms of sacred places, numinous feelings, and words as pilgrimages.

Sacred Places

The little girl who was coming back to life on the couch was different from the little girl I had kept to myself as a memory during my illness. . . .

The narrative of Cardinal’s search for liberation, a process she refers to as her “gestation,” is ordered by powerful places like the cul-de-sac, the doctor’s office, and the couch. She even chooses a specific spatial metaphor to represent her unconscious—she calls it “the castle of locked doors” or, elsewhere, the “castle of cards in whose dungeon I had been living for so long.” The Words to Say It begins and ends with the image of the cul-de-sac. It is referred to throughout the book. The cul-de-sac is a place of illness and injury, acting as a symbol of her injured, leaking womb and internal self: “The little cul-de-sac was badly paved, full of bumps and holes, bordered by narrow, partly ruined sidewalks.” Yet it leads to the doctor’s office where her inward journey “to be born again” takes place through conjuring up buried memories and undoing repressions. Most significantly, the doctor’s office and couch become the aperture to her childhood. Lying on the couch day after day, she not only brings her dreams and memories as offerings but, one day, also arrives at a crucial point of departure in which she starts to travel back in time to her bed-room, her childhood, and exchanges with her parents: “The child came to join me in the cul-de-sac. . . . The doctor’s office is my room. I am ten years old.”

The office and couch become her rabbit hole: “As soon as I lay down on the couch, I spread out the variegated materials of my dreams.” Into this new geography enters one parent and then the other. One passage in particular represents this theme of the opening into forbidden memories and traumas, as well as the synthetic work with her doctor to gather up lost pieces of her life:

In the dead end of the cul-de-sac, stretched out on the couch, looking up at the ceiling, my eyes shut, the better to establish communication with the forbidden, the unnameable, the unthinkable, I would find my father at last, thinking that his absence—his nonexistence even—had opened up in me a kind of deep and hidden sore in whose infections I would find the germs of my illness. So I applied myself to gathering up all memories of him, the merest thread of an image.

The psychoanalytic couch becomes a sacred place because it is where Marie Cardinal comes back to life, where she gathers the most crucial, precious, dangerous, and valuable fragments of her childhood and adolescence and places them “in perfect balance” with a new way of thinking about them. She says that this work was “in the nature of a miracle.”

Numinous Feelings

She put me in contact with the cosmos . . . a good fear.

Marie Cardinal’s work on the couch enables her to experience, and to choose words to express, the most extraordinary emotions in her life. Her account calls to mind the work of the German theologian Rudolf Otto, who identified as “numinous feelings” the deep religious emotions found in many of the world’s scriptures and oral traditions. Different from “ominous” feelings, numinous emotions are feelings of the greatest urgency, energy, and intensity and of a different quality from the emotions of love, trust, and salvation. Numinous feelings are experienced as overwhelming feelings of the uncanny, daemonic dread, and haunting “awfulness” as well as feelings of breathtaking bliss and joyful beauty. These feelings rise up unexpectedly and either overwhelm us with ecstatic intensity, or quietly fill the human frame to overflowing. In Otto’s view, a person’s capacity to undergo these emotional states is triggered by the awareness that one is in the presence of uncanny powers and primeval forces, usually referred to as Gods, gods, spirits, ghosts, or haunts, which appear to originate prior to and independently of an individual life. One has numinous feelings because one is in the presence of a “numen.” Yet Marie Cardinal’s writings suggest that numinous feelings are also generated in the dynamic intensity of relationships with mothers, fathers, siblings, and children. Cardinal’s narrative teaches us that the relationship, whether troubled or joyful, generates numinous feelings even when a numen is not present. Further, her narrative shows that the memories of the traumas and loves of childhood contain the residues of those numinous feelings that can be sparked to awareness again in adulthood.

The most powerful and deeply troubling relationship in Cardinal’s life is with her mother, a relationship that helped produce numinous feelings, including immense fears and periods of self-loathing. Running through the entire book are versions of this cry:

I’m afraid of everything. . . . I was afraid of the outside, but I was also afraid of the inside which is the opposite of the outside. . . . I was afraid, afraid, afraid, fear FEAR, FEAR. It was everything.

Marie Cardinal lives and breathes in a cosmos of fear. Its secretions exude from her pores and her womb. With images reminiscent of St. Teresa of Avila’s writings about her raptures of “terrible fear” and of being so “loathsome a worm” in the presence of an almighty deity, Cardinal is overrun in the face of the Thing living inside her:

I had the impression of sinking into evil, or imperfection, or the indecent, or the unseemly. . . . I looked upon myself as so much garbage, . . . overrun by error because of an evil nature.

And, later:

The Thing’s new weapon was more terrifying than what came before. More terrifying than the blood, more terrifying than death, more terrifying than the heart pumping with all its might. The new weapon was anxiety, pure, direct, dry, simple unmediated, without any protection, naked. . . . I was nothing. Nothing, to the point of dizziness, nothing, to the point of howling even to death.

To die. To die and finish it. I wanted to die, I wanted its mystery. I wanted it because it was something else, something incomprehensible for mankind, some-thing unimaginable. I wanted only the unimaginable and the inhuman. I wanted to dissolve into a charged particle, to dis-integrate into circular pulsation, to be annihilated. Nothingness.

These passages represent a “creature consciousness” of being submerged into a primordial chaos while in the presence of an overpowering Other.

However, some of Cardinal’s relations with her mother evoke the opposite pole of numinous feelings, where bliss and beauty are present. This affection between mother and daughter reflects part of the “love story” my students discovered in the book. For instance, Cardinal occasionally spent afternoons in gardens with her mother that filled her with a delicious sense of well-being. But it was the numerous nights under the starry heavens that opened up her mind and heart with a sense of spiritual wonder. One day on the couch, she recalls, along with “the chaos that had crushed me in my childhood, brilliant as a rock crystal, there also returned the recollection of Harmony.” Capitalizing the word Harmony signals that something extraordinary occurred when mother and daughter stood together in the darkness, open to the starry firmament, hand in hand, which she describes this way:

I was standing right next to her. She held my hand. She told me about the enormous distances separating us from these lights, some of which had already gone out even though we continued to see their reflection, so long was the path the light had to travel from there to us. She spoke of the moon, the sun, the earth, that fantastic pavanne that was danced by all the heavenly bodies, and us with them. This scared me a little and I pressed up against her, in her warmth and her perfume. But I felt her exaltation was in accord with the majesty of the subject. It was a good fear, a fear that ought to be exalting. To me, this great universe to which I had the good fortune to belong was beautiful.

Reflecting back from the couch, she asks two questions that suggest the heightened spiritual awareness born in these emotions:

Is it because of the harmony of these far-off nights that I accept my existence only to the extent that I feel it to be a cosmic one? Is it because of the accord that then existed between her and me that I am happy only when I feel that I am participating in a greater whole?

Words as Pilgrimage

Words swept away distrust, fear . . . sweetness, love, warmth and freedom.

Marie Cardinal’s sessions constitute a long pilgrimage of painful and yet exhilarating introspection with a ritual elder. Imagine if you can that Marie Cardinal and her doctor meet nearly 1,000 times (seven years at three times a week) as she discovers and uses words as instruments of revelation about repressed memories, forgotten scenes of humiliation, and to interpret astonishing dreams. Her doctor gives her the key to many of the locked doors with the repeated, simple admonition: “Talk, say whatever comes into your head; try not to choose or reflect, or in any way compose your sentences. Everything is important, every word.”

Yet she does more than “talk.” She invents, constructs, plays with words, and opens her mouth and mind to “that flood of words, that maelstrom . . . that hurricane.” At many points in the book she uses words to illuminate what words are and do for her journey. Words and the exchange of words are “precious events.” They are never-ending actions of potentiality about what is capable of coming into being. And they are more. She includes a litany of short paragraphs that read at once like poetry and scripture:

Words could be vibrating particles, constantly animating existence, or cells swallowing each other like phagocytes. . . .

Words could be wounds or the scars from old wounds, they could resemble a rotten tooth in a smile of pleasure.

Words could also be giants. . . .

Words could become monsters, finally, the SS of the unconscious, driving back the thought of the living into the prisons of oblivion.

I call these actions, events, and potentials her “pilgrimage of words.” Pilgrimage, as I use it here, means more than a person’s or group’s journeying to a sacred place. It involves arduous, sometimes dangerous, long-distance walking trips that skirt wild, unexplored territories. This kind of travel stimulates in the pilgrim the sense of wandering in a labyrinth. We know from the history of religions that the labyrinth has paradoxical powers. On the one hand, the design and complexity of the labyrinth protects the prize at its center, delays the discovery of the center of the world, and shrouds the truth from the seeker. On the other hand, the labyrinth is the only access to the center, the grueling avenue past its own obstacles and into illumination. Whether it be the pilgrimage to Campostela, the peyote hunt of the Huichol Indians, or the metaphorical pilgrimage of Dante, the traveler encounters serious discomforts, faces fears head on, meets darker forces, and survives only through courage, with the help of allies and sometimes simple good fortune. Cardinal affirms the pilgrimage nature of her work in many places, including when she self-mockingly turns her analysis into a circus scene reminiscent of Jean Genet:

The dead end had become the road to paradise, the route of my triumphal march, the channel for my energy, and the river of my joy. It would not have surprised me if this atrophied arm of the city had transformed itself into a fantastic parade ground. . . .

Leaping forward like a young buck, I would have made my dazzling entrance at the end of the cul-de-sac. . . . Beautiful enough to take your breath away! Beautiful enough for Playboy or for a stocking ad, LEGS . . . long neck, . . . long-waisted too! . . . Arms outstretched and slightly raised. . . .

The doctor would have raised his whip. . . . Pirouette here, somersault there! . . . And keep moving. Another headstand!

Her flowing, skillful words bring to her doctor’s office summers in Algeria that lived out their agony while hers was being implanted in her womb. She recalls with tenderness and careful observations the Arab and Spanish servants she lived with and learned from. She recalls the time when her adolescence began “to bite into the mind.” In time, she organizes words into a new language that has the power to transform her life. Picking up the themes of death and birth as well as the symbolic “distance” characteristic of initiatory pilgrimages, she writes:

For I think a well-conducted analysis must lead to the death and the birth of the subject in question, securing his own freedom and truth. There is an inestimable distance between the person I was and the person I have become, so that it is no longer even possible to compare the two women. And this distance between them only increases, for the analysis never comes to an end, it becomes a way of life.

In Cardinal’s case, her words are her legs and feet—they are the moving limbs that carry her back into childhood, enable her to “leave the heavy baggage of my life with the little doctor three times a week,” help her discover the “beastliness of my mother” and construct a more reassuring framework for the secret, the grotesque, and the hidden. They are living “witnesses” that accompany her, pointing out the key sounds, feelings, nights and days, streets, gutters, and body memories that were buried in the midst of family clashes and humiliations. These witnesses lead her into a measure of acceptance—acceptance of the size and depth of her illness, acceptance of the difficult parts of her personality—but most significantly, into participation in the transactions between the consciousness and the unconscious. Her description of these transactions combines an archaeological image with the hope of integration:

The unconscious going into the deepest strata of life to find riches which were all mine, depositing them on the one bank of my sleep; and consciousness on the other bank, inspecting the find from afar, evaluating it, leaving it behind to be presented or rejecting it, in this manner sometimes causing an eruption in my reality, a truth easy to understand, simple, clear, but which had not appeared to me before, not until I had been ready to accept it.

She uses words to unlock one of the most important doors in her “castle” of repressed memories when she deciphers a series of “signals” that appear one day in an overwhelming flood of outrage and tears. She works through her “crying jag, sobs, gulps” brought on by a simple parking ticket and uncovers a completely forgotten traumatic family event involving her brother and his cruel dismemberment of her favorite doll, a monkey on roller skates. On the couch, she relives the “whirlwind of fury,” the “murderous rage” of feelings that flooded through her on that distant day. She remembers being beaten by her mother for her protests and shoved into a bathtub where she is held down by her mother, her nanny, and her brother, who force water down her throat. She recognizes, for the first time since the trauma, the clash that erupted within her between, on the one side, an “earthquake” of hatred for her family and, on the other side, a “colossal power” that rises up in her to “seize hold of my violence, seal it off, and bury it” in order, she believes, to save her own life. She realizes that she had locked this scene and these feelings up in the castle for 30 years. On the couch in the cul-de-sac she realizes: “I, who preached nonviolence and never given so much as a cuff to my children . . . was, in reality, steeped in violence. I was violence incarnate.” Yet in her pilgrimage of words, she learns that the awareness of her own violence is an aid in her life. She writes:

This sudden revelation of my violence is, I think, the most important single moment in my psychoanalysis. In this new light everything became more coherent. I was sure that this force, rumbling constantly inside me like a storm that had been suppressed, muzzled and chained up, was the greatest source of nourishment for the Thing.

Once more, I marveled at the beautiful, complicated organization of the human mind.

Toward the end of her story, Cardinal tells us that this insight into her internal violence is a “splendid if dangerous gift.” Dangerous because it is always with her, but splendid because her awareness of its birth gives her some measure of control over its powers. Moreover, her awareness of this violence is accompanied by a gradual increase of her capacities for vitality, gaiety, and generosity.

I shall leave it to new readers of this captivating book to discover how Marie Cardinal brings her pilgrimage with her doctor to its fruition through her skillful interpretation of dreams—one involving a building in the forest and another a fantastic animal. Questions have been raised as to whether The Words to Say It is fiction or memoir, and how much of each. Clearly, this is no mere transcript of experience; this is a highly shaped work of literary art, whether one chooses to encounter it as a novel (as some in the psychoanalytic community apparently do) or as autobiography (as many other readers have tended to). I tend to concur with Toni Morrison, that Cardinal’s project was not so much fictional as documentary, and that Cardinal used the literary strategies of a novelist to shape her story. The result, in my view, is that this “autobiographical novel” renders the impact of horrifying yet liberating experiences in persuasive, powerfully transformative prose. Her dynamic and creative use of words brings to life for us the mutual work with her doctor that allowed her to “put in perfect balance” her capacity for horror and the grotesque with her capacity to love herself, her children, and her husband. It is this exhilarating balance that she carried with her, on that final day out of her doctor’s office, when she was filled with an “appetite for life and for building as big as the earth itself.”

Davíd Carrasco, Rudenstine Professor of the Study of Latin America at Harvard, is a historian of religions specializing in Mesoamerican religions and the Mexican-American borderlands.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.