In Review

Medicine’s Unique Ways of Knowing

An interview with Janet Gyatso

By Wendy McDowell

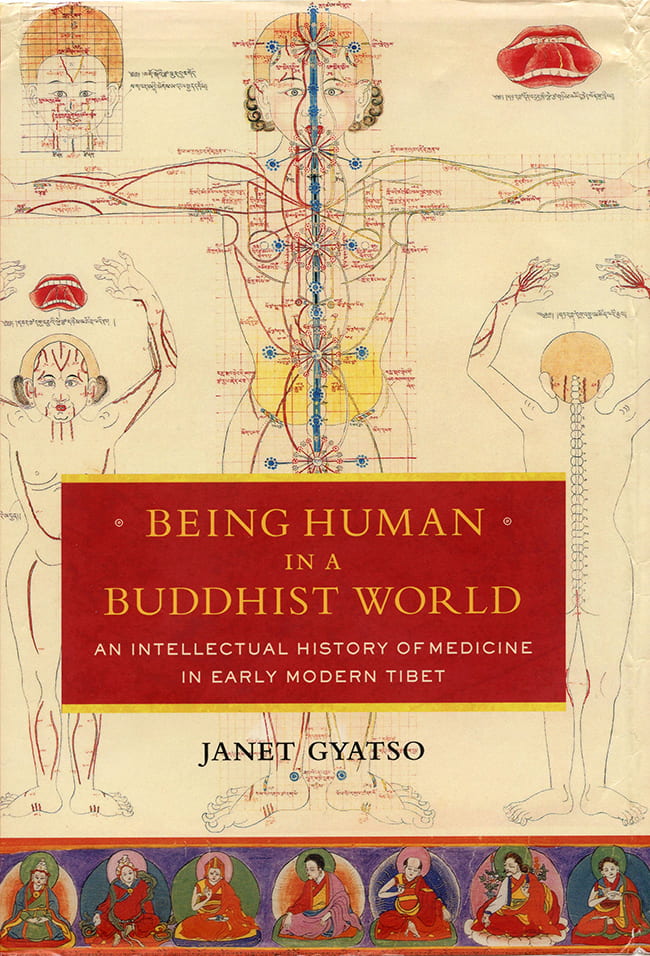

Ten years in the making, the most recent book by Janet Gyatso, Hershey Professor of Buddhist Studies, endeavors to “stand next to my colleagues from a Buddhist world,” as she puts it, and “watch with empathy and care as they attempt to carve out a space for medical learning” (19). Wendy McDowell ventured into this world with her in a recent conversation.

As a scholar of Tibetan Buddhism, what led you to be interested in the intellectual history of Tibetan medicine?

This book happened by accident or fortuitous circumstance, depending on how you look at it. After my previous book on autobiography,1 I wanted to do more on gender theory and gender representation, but I wasn’t sure where to go in terms of Tibetan sources. This was in the late 1990s, when I was still at Amherst College. There happened to be a Tibetan historian of medicine who taught Tibetan medicine not far from where I was in Western Massachusetts. It dawned on me, “Why not look at what medicine has to say about gender?” This was something that few at the time would think to do, since our focus in Tibetan studies had been almost wholly on religion, and almost no one had even looked at the remarkable twelfth-century medical work, the Four Treatises.

So I started reading the sections of the treatise that talk about sexual identity and gender . . . and, honestly, what captivated me more than anything was the tone, how different it was. It was coming from a very different place than the way texts exploring religious themes were written, and that difference spoke to me—I found it refreshing. I think a lot of this has to do with my own proclivity. I like material that is very straightforward, that’s materialistic in a certain way.

Your opening line is: “This book studies how knowledge changes.” But you immediately signal that simplistic models of change aren’t adequate, since you need to account for “double movements.” What do you mean by this, and how do you do it?

This is one of the big themes of the book, that the figures and the texts I’m studying talk out of both sides of their mouths at once, to put it colloquially. The big issue at stake had to do with allegiance to a model of authority, and to notions of knowledge that are loyal to the Buddhist worldview, which has had a huge presence in Tibetan intellectual history. But the physicians and commentators were interested in kinds of knowledge that necessarily have to go outside of those Buddhist paradigms, and religious paradigms more generally, and they find themselves having to engage in a lot of complicated moves in order to make things work.

One of the important skills to cultivate when doing this kind of scholarship is to not take rhetorical moves in a text at face value. That doesn’t mean you can simply ignore what is being said and insert your own judgment: “Oh, they say this, but this is not what they believe.” That’s way too naïve, and imperialistic. How do you take seriously what the texts are saying, but also discern that other things are going on under the surface that, for particular reasons, the authors are not mentioning? It may be conscious, or unconscious, or subconscious, or a question of etiquette, so there are a lot of things a scholar has to take into account. This is what we try to teach our students, how to do a so-called “close reading.” When you practice this skill, you start to pick up that what you’re seeing on the surface is just the beginning, and your task is to figure out all the things that have contributed to that surface view.

Your book begins with the heyday of Tibetan medicine in the seventeenth century, then goes back a century, and also refers to the twelfth century. Why this backward movement?

For one thing, I wanted to start with the medical paintings overseen by Desi Sangyé Gyatso,2 because they are just so amazing. Also, I wanted to get out of the tired model of tracing a chronological development, because I don’t think the important issues at stake are strictly speaking chronological. Some of the most important and “modern” things that were happening in the history I discuss were present in the earliest moment. I don’t use the term “modernity” very much in the book—it’s an overused word right now and I didn’t want to enter fully into the debates about it, although they’re implicit. But I do focus on modern sentiments and orientations that are present quite early on. In fact some of these are even more evident at first and then get covered over later.

So I decided it was much better to open the book by turning the reader on to the utter delight of the medical paintings, especially since they helped spark my own interest. When I first looked at all seventy-nine plates of these unbelievably detailed and gorgeous illustrations, I was captivated.3

Besides, the seventeenth century is a very important historical moment where things come to a head in Central Asia. The Tibetan state reaches the apex of its own history at this time. The Qing dynasty in China comes right after this, and things get even more complicated between the Tibetans and China.

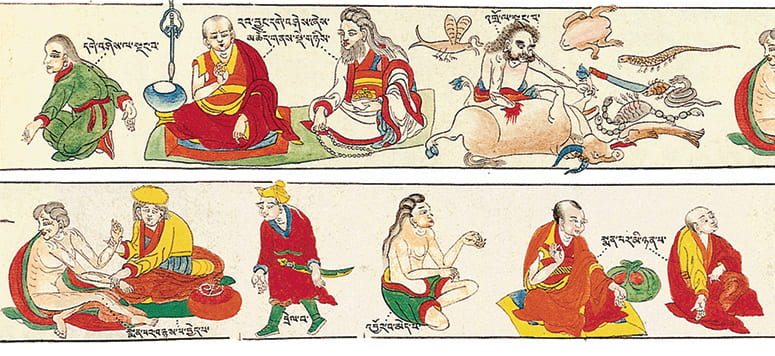

Kinds of people not to take on as patients. Plate 35, detail

Unlike most illustrated scrolls from before this time, the medical paintings were focused on the ordinary social and material world. Did their quotidian nature attract you?

Yes very much. But it’s also the attitude, and the freedom, that you see in the artist’s hand in these paintings. What really struck me was the paintings’ frequent irony, and the fun that the artists clearly were having. Of course, painting the quotidian is probably what allowed them to take such liberties, because they weren’t as bound by religious iconography or as worried about committing a travesty against certain religious values. Where I come down at the beginning and end of the book is that the be-all and end-all for medicine is keeping people’s bodies alive. Yes, ethical and religious considerations come in too, but survival of the patient is the bottom line. And that is a totally different mindset from one that is focused on religious realization.

But was this necessarily so?

Well, no, not necessarily so. That’s also what’s interesting about the Tibetan case. There is so much premodern medicine that is completely taken up with “ritual healing” or “spiritual healing,” and you find that widely in Tibet too. But not in the medical tradition called Science of Healing (Tib. Sowa Rikpa) that I write about. It is not entirely absent, but it’s far from the main issue.

Were you surprised by this?

Yes, I would have expected there to be more focus on religion and ritual, and I was surprised by how little there is. I will say that I’m in a debate with a bunch of my colleagues right now who are saying, “No, no, no. You can’t draw a strict line between religion and science, or spirituality and medicine, in a place like traditional Tibet.” I am saying that it is not a strict line. And if you keep focusing on the fact that you cannot draw a 100-percent strict line, you’re going to miss some extremely important distinctions that can still be made. I also feel that the attitude I am questioning can pander to an Orientalist way of thinking: “Tibetan medicine is so Buddhist. It’s so spiritual.” This fails to acknowledge that even if they’re not right about physical ailments as compared to modern science, these medical thinkers questioned religious and scriptural authority and were concerned most of all about empirical verification.

Can you provide a quick snapshot of medical training during the periods you discuss?

Tibetans had a good idea of medical education as distinct from a Buddhist or religious education. But the academic teaching of medicine primarily occurred in small schools within monastic compounds. We can locate a bunch of them in various places, starting in the fourteenth century, if not earlier. What changed during the time of the fifth Dalai Lama is that a freestanding, separate medical college was built in Lhasa. Unfortunately, it’s hard to determine how this college was structured, or what the mix of the student body was. It seems like the students were primarily monks who did have ritual duties—such as chanting for the health of the fifth Dalai Lama and for the Tibetan state. But they also had classes and engaged in straight-ahead medical learning, which involved going out into the field. A big part of what they learned was how to identify medicinal plants. In the paintings, medicinal plants are illustrated with incredible detail.

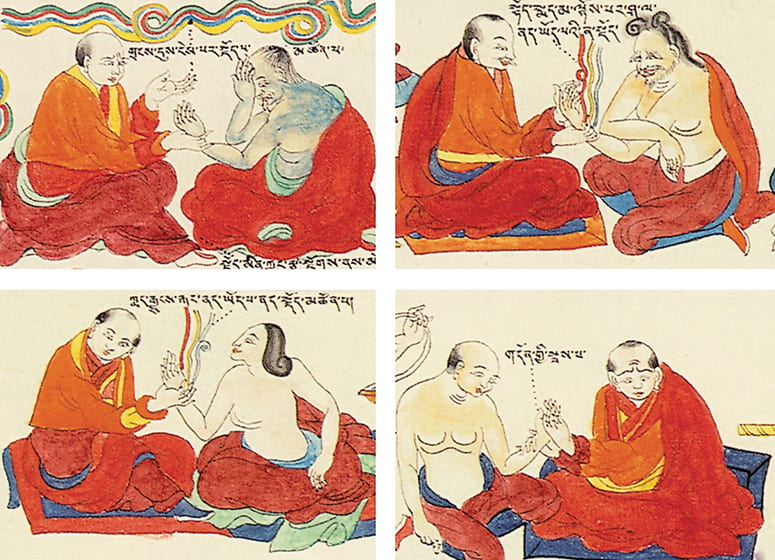

What were their diagnostic practices?

One major diagnostic is pulse, according to a basic system shared with Chinese medicine.4 This involves a very subtle process whereby the physician listens to the rhythm and the sound and the beat of the pulse. It’s not like Western medicine, where we count how many pulse beats occur per second. It is more about listening to the quality of the pulse—how it “sounds” or feels, and its regularity or irregularity. Tibetan medicine provides interesting descriptions like, “This particular pulse sounds like a mosquito batting its wings across a large field of barley.” What the doctor is trying to figure out is which organs are being affected by an illness. The practice is also influenced by the idea of humoral balance, which comes from Indian medicine. The three humors are wind, bile, and phlegm.5 Tibetan medicine also uses a fascinating diagnostic having to do with urine, which I don’t know as much about. Physicians would study a patient’s urine—its color, how clear it is, or if it has sediments in it, and they would smell it carefully. There’s an entire chapter on that in the Four Treatises. Additionally, physicians would listen closely to the patient’s description of her symptoms, look at the color of the patient’s skin, and assess the general sense of vitality.

Physicians taking patients’ pulse. Plate 61, details

What did the medical paintings mean for traditions of representation in Tibet? Did they open up new ways of seeing?

It seems that representation was opening up at the time, anyway, in part because of other efforts by the Desi. In the Potala—the main residence of the Dalai Lama in Lhasa—we also find wall paintings of activities that were going on in the court and in the city at the time, including races and swimming contests, and historical personages. These, too, are painted with exquisite detail. One of my remaining questions is: to what degree did the opportunity to illustrate something like medicine get artists more and more involved in the illustration of the quotidian?

But with the death of the fifth Dalai Lama, and then the assassination of the Desi Sangyé Gyatso—who was probably killed by the Mongol warlord in Lhasa during the time of the disputed sixth Dalai Lama—my sense is that this flourishing of culture came to something of a halt. However, in other domains, such as writing, we still see increasingly candid autobiography during this era. People are writing about their lives in much more concrete and specific and personal ways, and not always addressing how this relates to enlightenment and the Buddha. I think medicine was part of a movement that was unfolding quickly in the late seventeenth century, but then other forces mitigated against it going further into empirical science.

One of my favorite passages begins, “ ‘Everyone and anyone.’ That sums up the visual message” of the paintings. This seems to be a pretty radical, egalitarian thing to do—in any time!

That’s right, and that’s one of the interesting things about medicine. At least in theory, though maybe not in practice, there is no difference between a rich or a powerful person’s body and an everyday or a poor person’s body. The ills of the body are equalizers. We all have to die. Every single one of us. Everyone and anyone.

And yet, what I pointed out in that same passage is that you have all this extra detail in the paintings that strictly speaking is not really needed. So on the one hand, they’re saying “everyone and anyone,” and on the other hand they’re saying “Look at how different people are. They all have a liver, but some of them have bushy eyebrows, some of them are bald, and some of them have thick, curly hair.”

In your chapter “Anatomy of an Attitude,” you discuss the Desi himself, who doesn’t pull punches in his critiques. Was this unusual?

The Desi was very arrogant, very entitled. Part of this was because he was the favorite of the Dalai Lama, and he was elevated very high. He was also brilliant. Not only was he active in medicine, he was active in the portrayal of the Tibetan state, and of the institution of the Dalai Lama. He wrote in great detail about other topics, such as law, the structure of monasticism, and astronomy. He also wrote detailed biographies of the Dalai Lamas, and about the ritual cycles in the city of Lhasa, and how the city should be used. He was hugely productive. It is not surprising that he ended up getting assassinated, because he was a politically ambitious operator.

Of course, it is not only in medicine that Tibetan scholars disagreed with one another. They argued and fought with each other over theology and epistemology and soteriology all the time. I’m working on poetics now, and how Tibetans have used the art of poetry to make jabs at each other. This was a competitive, agonistic, and sectarian culture. But medicine was one of the places where such debates took surprising turns.

You suggest that the medical treatise advises doctors to poach other doctors’ patients!

Absolutely, and it even suggests ways doctors can boast to make themselves look better! They could do that with less inhibition than would occur in a Buddhist context, because Buddhist ethics focuses on humility, total generosity, and compassion to all. You’re not supposed to be competitive with others who are also doing good, since you should be working together. So this is an interesting part of Tibetan medicine that maybe helped contribute to a combative culture more generally, by being a place where it was more or less recognized that competition is a fact of life. Of course, in philosophical and metaphysical disputes within the Buddhist context, they beat up on each other, too. They would say, “Are you an idiot? Have you never read anything? How could you possibly say this dumb thing?” It’s just that medicine is more up front about it, and the text will actually discuss how it’s good to engage in practices that will get and keep patients.

Janet Gyatso

Chapter four, “The Evidence of the Body,” opens with a famous bone-counting experiment.6 You suggest this represents the growing quest for empirical evidence of medical knowledge, but also reveals the growing impulse to reconcile science and religion. What’s important about the way debates like this played out?

As a French physician told me long ago, when you open up the body, you find a big, murky mess! You have to pull everything apart to identify the organs and vessels and so on. How you identify what is what is a complicated issue. For the Tibetans, there was a difference between two understandings of the channels of the body. In yogic traditions, there are wind channels, and energy channels that are important for mobilizing bodily forces. But these didn’t match what the doctors thought they were seeing when they actually opened up and looked at a dead body. And so the physicians and commentators had a difficult problem. They didn’t want to say the Buddhist yogic system is wrong. So they came up with various strategies. One of the main ones was to put the yogic channels into the embryology. This way you can say that when the body is first conceived, it does have these subtle yogic channels. They are not visible in the normal adult body (or its corpse) but can be mobilized if one practices yoga. With this tactic, they don’t satisfactorily answer the question of the incommensurability of the two systems, but they sweep it under the carpet. That allowed them to spend their exegetical energy on the empirical channels.

Because the Tibetan doctors do blood-letting—this is one of their biggest therapeutic practices—they can’t be messing around with an inaccurate anatomy of the body if they’re trying to draw blood. The same is true with moxibustion—you need to know exactly where the nerves are to do it correctly. So the physicians really need to know whether their maps of the nervous and vascular systems are accurate. I think I use the metaphor of a tightrope a couple of times—because the medical theorists were trying not to antagonize the religious establishment, and yet they wanted to have a space where they could look into the empirical facts about the body unencumbered.

What are some of the issues with respect to gender? Did the texts surprise you here, too?

As is true everywhere, you find misogyny, patriarchy, and androcentrism in the Tibetan medical texts. For example, the classical Buddhist notion of low merit is used to disparage the female body and its physiology. But when the physicians get down to describing diagnostics and therapeutics, they seem to drop that language. Sometimes it seems like two different parts of the medical brain are not communicating with each other.

One surprise for me had to do with the recognition of the sex of a child. Both Indian and Tibetan medicine have a broad vocabulary to describe kinds of sexual identity all along the axis between the normative male body and the normative female. Tibetan medicine ended up naming a third sexual identity, as an in-between catch-all category. This fascinated me as a recognition that any absolute bifurcation between male and female has to be broken down in order to account for what is observed in real human bodies. That also inspired the medical theorists to come up with a term that would name gender as distinct from anatomical sexual identity.

You note that Tibetan physicians did create what we would call women’s medicine.

Yes, that’s another thing that happened in Tibetan medicine. It doesn’t amount to much, but symbolically it might have meant something. There were eight branches of medical inquiry in India, but the Tibetans merged two of the branches so they could make room for a women’s branch. This shows that they recognized there is something particular to the female body that needs separate attention. They also realized that medicine of the past was androcentric, and was likely to ignore the specificities of female bodies and the particular conditions that afflict them.

Some of your poignant observations—about how physicians are forced to recognize the fragility of life even as they try to save and protect it—seem to be new realizations. Did your view of the medical profession change as you were engaged in this project?

Working on this book definitely did draw my attention to how fascinating the field of medicine is altogether. It also made me see how there are so many different types of knowledge. I found myself being most interested in how much of medical knowledge is bodily and experiential. This made me wish that, if I were able to start my life over again, I could be a doctor. Actually, my son is currently a first-year resident at University of Pennsylvania Hospital. When he first started medical school there, they had an orientation for parents, which put us through a few exercises to show how doctors are trained. One of the main things they stressed was the importance of collaboration, and how doctors can’t operate on their own without consultation and communication. These are different ways of knowing than those which assume an independent autonomous agent. A doctor has to remain embedded in a social and material world. I love that intermediate space between the entirely material and the entirely mental. That is what I continue to be interested in, going forward in my work.

Notes:

- Apparitions of the Self: The Secret Autobiographies of a Tibetan Visionary (Princeton University Press, 1999).

- Desi Sangyé Gyatso (1653–1705) was the chief minister and then regent of the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Losang Gyatso (1617–82). The paintings “are closely tied to . . . the massive four-volume commentary to the twelfth-century medical root text Four Treatises, written by the Desi” (24).

- Serindia Press was very generous in allowing me to reproduce many of these vignettes in my book. The entire set can be found in Tibetan Medical Paintings: Illustrations to the Blue Beryl Treatise of Sangyé Gyamtso (1653–1705), ed. Yuri Parfionovitch, Fernand Meyer, and Gyurne Dorje, 2 vols. (Serindia, 1992).

- Scholars who research this topic see a complex exchange between techniques that were developed in Tibetan medicine and techniques developed in Chinese medicine.

- This has close analogues in Greco-Arabic medicine, which sometimes adds a fourth humor, blood.

- Darmo Menrampa Lozang Chödrak (1638–1710) was “another medical star from the heyday of the Fifth Dalai Lama’s rule” (193). As is recounted in the book, “at some point around 1670, apparently perplexed by the differences and vagaries in various medical works around the number of bones in the human body, Darmo decided to gather his students together and let the body speak for itself” (193).

Wendy McDowell is senior editor of the Bulletin.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.