In Review

Facing the Fierce Land of I

Gandhi’s translation of a verse from the Bhagavad Gita invites and commands us to return to what’s essential before taking action.

Dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra. Wikimedia Commons, CC-PD

By Eliza Griswold

Act . . . without attachment, steadfast in yoga, evenminded in success and failure. Evenmindedness is yoga.1 —The Bhagavad Gita, chapter 2, verse 48

I wandered into the Quaker meeting house off of Brattle Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The doors were open, and I slipped inside to meditate. Through the large windows, the butter-yellow light of early fall clattered off the trees outside, their leaves still unfallen. The spare panes invited nothing but reflection.

And yet I resisted.

The kind of meditation I practice, Vedic meditation, is pleasurable and easy. I call it meditation for dummies, in that it requires nothing but the repetition of a single sound—a seed syllable, or mantra—for twenty minutes or so, with closed eyes. For no seeming reason, I was afraid to close my eyes and to begin.

The problem wasn’t me, it was I.

I is a troublesome character in my life. She grasps for gold stars and achievement with a relentlessness that I believes the modern world demands. Driven by a desire for success and fear of failure, I often refuses to sit still. She refuses to do anything in which the gains and goals aren’t stunningly clear. I is often told that her definitions of success and failure are outmoded, inherited relics of another culture. She may agree intellectually, but ask her to give up her personal hierarchy of prizes and publications, and she balks. She relishes the crossing off of items on any To-Do list. She’s very, very busy and that, of course, means she’s very, very important. Oh, poor put-upon I, how does she possibly do it all?

In the meeting house, I was being asked to do nothing, and she didn’t like it. It wasn’t that I feared closing her eyes and finding emptiness. Just the opposite. I feared closing her eyes and finding fullness, purpose that would require her to renounce attachment to the world she so covets.

Moreover, since I exists only in motion, to ask her to sit still can be quite challenging. She fights and squirms and rolls her eyes around. She is a human doing, not a human being. And I is very, very tired. She has run for a long time on the hybrid fuels of self and fear. The good news about these toxic forms of energy is that they’re not renewable, and even she understands they are running out, leaving her ego-driven engine coughing and sputtering toward a shallow grave.

Eliza Griswold.

Faced with obsolescence, I had a stroke of luck: David Hempton, Dean of Harvard Divinity School, invited her to apply for a Berggruen Fellowship. Although her chosen course of study includes data mapping of Syrian artists and poets fleeing a ruined country, it also involves the quieter tasks of puzzling through Sanskrit with Frank Clooney, a Jesuit and renowned scholar of Hindu scriptures, as well as writing her own poems. This year is designed to be laden with the one resource that often eludes her: time.

Yet here I was in the meeting house with nothing to do. None of her usual selves were in demand. There was no deadline of the moment, no reporter’s visa to a war zone to procure, no class to rush off and teach, and no three-year-old to whom to attend. (The latter was safely ensconced in New York City.)

Given this gift of a fellowship, she’d designed this year to contain exactly the kind of quiet in which she found herself sitting. Now inside it, I was terrified.

The verse above from the Bhagavad Gita is both an invitation and a command to live a different kind of life. It is an intensely modern call, and yet it comes from a piece of scripture at least two thousand years old. The Bhagavad Gita, which in Sanskrit means “The Song of the Lord,” is part of the larger Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, ten times the length of The Iliad.

The story of the Gita, as it’s often called, unfolds on a battlefield in the form of a conversation between Lord Krishna, an incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu, and the hero, Prince Arjuna.

As the two stand poised on the verge of the bloodiest war of succession of all time, Krishna, who is driving Arjuna’s chariot, instructs the hero as to why it is his duty to fight and kill his own family in the coming war. This, in itself, is a radical command. How can it be right to shed blood, let alone the blood of one’s family? In this, the Gita asks, and answers, the most challenging questions of existence.

But the answers aren’t exactly straight ones. They tend to be circular. There are 700 verses in the Gita; each is a couplet called a shloka. Many function from line to line as a form of call and response, not unlike the Psalms of the Hebrew Bible. Like Zen koans, many verses defy the intellect. They are puzzles, spiritual conundrums. Their circular nature is such that the mind must return to the start. This isn’t an intellectual exercise; it’s the nature of practice. This verse, like others, bends the mind to reach the soul. Yet to call them riddles would be like calling Chaucer a drunken singer of bawdy verses.

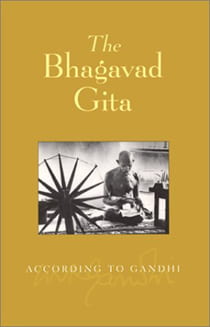

The Bhagavad Gita According to Gandhi

In many of these couplets, including verse 48 of chapter two, Krishna defines right action for Arjuna by laying out a challenge of how to achieve what Mahatma Gandhi translates as evenmindedness. This evenmindedness has many names—equipoise; equanimity, for followers of St. Ignatius of Loyola; indifference. The interpretation I prefer belongs to my meditation teacher: being.

To read a bit more closely, let’s begin where the verse does: yoga-stha kuru karmani. Word for word, this phrase translates: standing in yoga perform actions.

As interpreters, our first challenge is to define yoga.

Discerning the meaning of yoga is a tricky task for a worldly reader steeped in the image of sweaty postmodern rear-ends engaged in what a friend calls “competitive bending.”

The rest of the verse is dedicated to defining what this yoga is, and how exactly we are to stand in it.

Let’s continue, phrase by phrase:

sangam tyaktva dhanamjaya / Having abandoned attachment, O Winner of Wealth (one of Krishna’s many names for Arjuna)

siddhy-asiddhyoh samo bhutva / Accepting success and failure with sameness (Gandhi’s evenmindedness)

samatvam yoga ucyate. / This sameness is yoga.

Let’s explore this a bit. This sameness, this equanimity, is the ability to face success and failure with detachment. My meditation teacher, Thom Knoles, interprets this profoundly unruffled and openhearted indifference simply as “being.” The way to stand in yoga is to meditate, to dip below the relative world—the land of I—and connect with an underlying and universal field of consciousness. Meditation becomes the means of returning to—marinating in—one’s essence.

Now let’s run the whole together, in a slightly more plainspoken variant than Gandhi’s translation above, in order to stick as closely to the original as possible:

Standing in yoga perform actions.

Having abandoned attachment, O Winner of Wealth,

having accepted success and failure with sameness. This sameness is yoga.

Now that we know what the verse means, let’s confront its central question, which is nothing less than, How shall we live?

To answer, let’s consider how it is to stand in yoga. Or, more clearly put, how do we ground ourselves in what matters? How do we ground ourselves in being in the midst of our contemporary lives? Apparently, this isn’t a new question.

For me, the answer lies in dipping the small self into the vast underlying field of consciousness. It lies in meditation for dummies. Yet there are myriad forms of practice, endless doorways, and the only ones to watch out for are those guarded by keepers who argue an exclusive claim on The Way.

A walk in the woods, prayer (whatever that may mean), service to others—there are endless ways by which we return to what’s essential before we take action.

One useful analogy for this experience of grounding in being—one that even a chronic doer like I can accept—is that of the bow and its arrow.

The bow is just a stick unless one knows how to bend it.

Then, the farther back one draws the string, the straighter and more forcefully the arrow flies.

Grounding in being is pulling back that string. Acknowledging the value of the divine pause before taking action requires I to undergo a fundamental shift. She no longer runs the show.

I got very freaked out once in India when invited to bow to an ancient photograph of her teacher’s teacher’s teacher. A voice within shouted, with the brimstone of the Old Testament—Thou Shalt Have No Idols before Me! She wandered away with her yellow chrysanthemum and made her offering elsewhere. It was only later that a friend suggested that perhaps the act of bowing had nothing to do with some kind of freaky culty guru business. Maybe bowing was about placing the head below the heart—a reordering of the role of the intellect, the fierce land of I, by acknowledging that it is not supreme.

On that recent afternoon at Cambridge Friends Meeting House, I nearly won. A bellyful of caffeine and the phony restorative promises of her recently consumed smoothie stoked the fires of self-importance. In the end, however, the practical aspects of meditation got her. She hates to admit it, but she knows that even she sleeps and works better after divine pause. Whenever she can bend her mind below her heart, she drops below the harried nonsense by which she defines herself.

I has clung to troublesome terms of success and failure since the third grade, probably, when she played both George Washington and the Hessian general in the school play. She also did the lights—every scene was a virulent blue. Even now, when asked to step into the spotlight, her fear comes up. Who am I, and what is my value, she asks us, if I don’t strive after the shiny things of this world?

Oh, she’s young, this one—a factor too easily forgotten when she believes she’s in charge. To grow quiet, she must be reassured that she has a place within, just perhaps a smaller part in the play. And, yes, she can still work the lights. And she calms down, of course, when we tell her she’s doing the work she’s intended to do this year, on this generous fellowship, and at Harvard, no less. Let her have a gold star!

There’s a line from Wallace Stevens that reads, “the life of the poem in the mind has not yet begun.”

The Gita invites us to just such a beginning—a means to practice being human.

Eliza Griswold is a poet and reporter whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New York Times Magazine, Harper’s, and the New Republic. Her books include The Tenth Parallel: Dispatches from the Fault Line Between Christianity and Islam (FSG, 2010), and I Am the Beggar of the World: Landays from Contemporary Afghanistan (FSG, 2015). Her new book, Amity and Prosperity: A Story of Energy in Two American Towns, about how fracking destroyed a rural Pennsylvania town, is due out in 2018.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.