In Review

Ethiopian Lives and Liturgies

By Kay Kaufman Shelemay

The curtains to the Holy of Holies open and three priests emerge, each one supporting on his head a cloth-wrapped tabot, a sacred altar slab made from wood or stone replicating the Tablets of the Law. Each priest’s vestments, seen from the front, are covered by richly embroidered cloth draping down from the tabot. When viewed from the rear, each of the three figures appears as a solid block—similar to the altar chest on which the traditional tabot rests. Turbaned musicians in white robes stand several steps below the three priests, deployed in two lines facing each other, all singing the traditional chant and swaying to the resonant beats of the kabaro, the large kettledrum. Each musician shakes a small metal sistrum in his right hand, while his left anchors a prayer staff extending back over his left shoulder. The musicians are led by the liqa mezemrat (master of liturgical chant), Moges Seyoum, who stands second from the rear in the right-hand line of musicians, a microphone instead of a sistrum in his right hand. Behind him and to the right of the tabot procession, one can just glimpse the bearded face of the abba, the church elder, flanked by priests, one of whom carries a large ceremonial cross. The tabot procession, shadowed by large ritual umbrellas, proceeds down the center aisle of the sanctuary and then around the circumference of the entire hall. The musicians and choir follow, trailed by members of the congregation, who sing, dance, and ululate. When the procession ends, the priests return the tabots to the altar and close the curtains to the Holy of Holies.

If the elaborate rituals of Ethiopia’s venerable Orthodox Church might seem to be relics from a distant land, the 1974 Ethiopian revolution and subsequent migration of millions of Ethiopians abroad has introduced Ethiopian Christianity to all corners of the globe.1 Among these locations is Washington, DC, where the procession described and pictured above took place at Debre Selam Kidest Mariam (St. Mary’s) Ethiopian Orthodox Church on January 27, 2007. The late-twentieth-century dispersal of Ethiopians worldwide may strike one as unexpected, given Ethiopia’s longtime status as a global symbol of isolation and stasis. Did not the eighteenth-century writer Edward Gibbon state that, by virtue of their location in the mountainous highland plateau of the African Horn, “the Aethiopians slept near a thousand years, forgetful of the world by whom they were forgotten”?2 If Gibbon overstated the historical isolation of Ethiopia—which had, in fact, for more than a millennium supported an ecclesiastical community in Jerusalem and also initiated other contacts with the outside world—he would have been even more startled at the pace at which late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century Ethiopians have become global citizens. Heirs to a church founded in the fourth century, when shipwrecked Christian missionaries from Tyre converted the Ethiopian court, Ethiopian Christians have in recent decades transmitted their esoteric liturgical tradition far and wide.

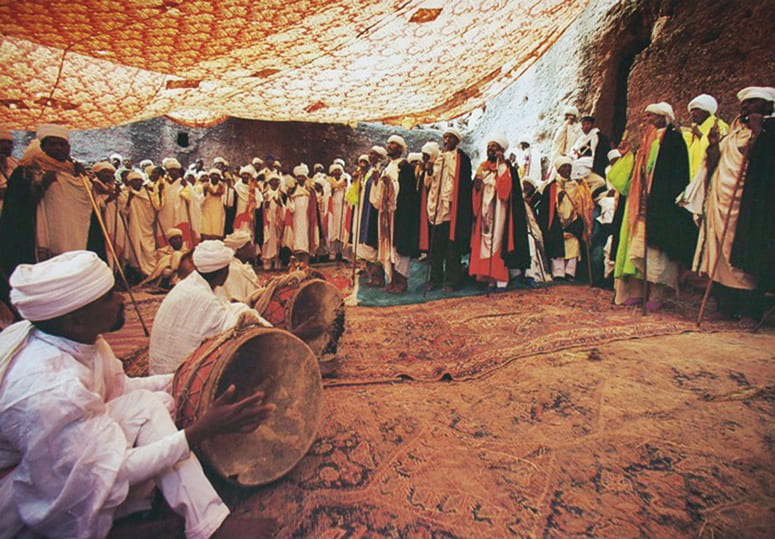

The Christmas ritual at the rock churches of Lalibela in Ethiopia, c. 1974. Photo by Peter Takacs

The Ethiopian synaxary credits the large repertory of Ethiopian chants to the creativity of a venerable church musician named Saint Yared, who is said to have been inspired by the Holy Spirit during the sixth-century reign of Emperor Gebra Masqal. Performance of this liturgy has remained at the heart of Ethiopian Orthodox religious practice ever since, just as the Ethiopian Church itself has expressed the core of Ethiopia’s official national and religious identity for centuries. But, in 1974, the Ethiopian revolution began and the long-standing hierarchies of Ethiopian religious and social life were turned upside down. With the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie I, the church lost its symbolic, but powerful, head and, with the subsequent nationalization of rural and urban lands shortly afterward, it lost its economic base as well.

As Ethiopia became increasingly chaotic in the mid-1970s, Ethiopians began to flee their country and to seek asylum abroad. Thousands, especially Christians of Amhara ethnic descent, left the country through whatever means were possible; over time, they established new communities worldwide. Among these refugees were an unusually large number of church musicians vital to the establishment of Ethiopian Christianity abroad. Here, I will introduce two important church musicians, both of whom have helped found Ethiopian churches abroad and have remained central to Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity’s new global presence.

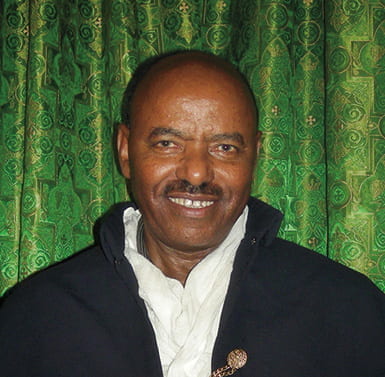

L. M. Moges Seyoum. Photo by Marilyn E. Heldman

The first is L. M. Moges Seyoum, a leader at St. Mary’s in Washington, DC. His peripatetic life was surely one he could never have anticipated or even imagined during his formative years. Born in a rural area of the central Ethiopian highlands in 1949, Moges3 began studying chant in his local church as a young child. His father was a marigeta (leader of church musicians) and a teacher and scholar of chant. Like many young boys, Moges followed in his father’s footsteps (as did his two older brothers), becoming a marigeta. At fifteen, he left home for Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, where he both continued his secular education in a military high school and achieved at church schools the status of “master for aqqwaqwam,” the advanced study of Ethiopian liturgical dance and instrumental practice. This was also an era during which the emperor placed a high priority on sending talented young people abroad to study, and Moges left in 1970 to study theology and law in Greece. When the Ethiopian revolution began in 1974, with violence soon breaking out at home, Moges decided to remain abroad. He left Greece in 1982 when he received asylum in the United States.

Moges Seyoum arrived in Dallas, Texas, in the heat of August 1982. At first, he helped lead the liturgy at a local Russian Orthodox Church, with knowledge he had acquired during his sojourn in Greece. But with the Dallas metropolitan area home to an increasingly large number of Ethiopian refugees, Moges quickly helped found the Ethiopian Tewahedo Debre Meheret St. Michael Cathedral in adjacent Garland, Texas. Over the years, he made visits to other Ethiopian churches throughout the United States and, in 1989, accepted an invitation from Debre Selam Kidest Mariam Ethiopian Orthodox (St. Mary’s) Church in Washington, DC, to lead its liturgy.

The Christmas ritual at St. Mary’s Ethiopian Orthodox Church, January 6-7, 2011. Photo by Kay Kaufman Shelemay

Today the Washington, DC, metropolitan area hosts the largest Ethiopian community outside of Ethiopia, estimated to be more than one-quarter of a million people, and is home to more than a dozen Ethiopian Orthodox churches. St. Mary’s Church has grown to be one of the largest Ethiopian churches in the diaspora and has a critical mass of priests and liturgical musicians able to ensure performance of the liturgy in a form very similar to that of the Ethiopian homeland in the past. There are enormous challenges facing Ethiopian Orthodox churches seeking to maintain the traditional ritual cycle, including its musical content, in diaspora. While the Mass can be chanted by a single priest and is relatively straightforward to perform in the diaspora setting, the musical liturgy celebrating annual holidays requires a number of trained musicians proficient not just in the large and esoteric corpus of chants set in the three distinct musical modes, but in the ability to perform a given chant in multiple and subtly different renditions with varying instrumental accompaniment and dance. Full performances of these lengthy rituals celebrated on annual holidays, saint’s days, and other important occasions, ideally require two groups, each with a dozen musicians, standing opposite each other accompanied by drummers playing the kabaro.

Even large churches such as St. Mary’s face mounting challenges, especially as their well-educated priests and musicians age. All congregants except the clergy and musicians lack familiarity with the liturgical language, Ge‘ez. In diaspora, the many demands of immigrant life render impossible the day-to-day engagement with the traditional liturgy that sustained the tradition among congregations at home in the past and encouraged young boys to pursue a liturgical career. Moges Seyoum is well aware of such challenges to the future of the tradition, which has led him to take action:

I have to teach. . . . When I was in Ethiopia, it was OK; I didn’t have any problem, because a lot of students needed to follow the zema [chant], the aqqwaqwam [instruments and dance]. Now we don’t have time in this country. You know, everybody works, and just the younger generation follows a class in English language.4

In light of the pressing need to transmit the liturgy, since 2000 L. M. Moges has offered a weekly class on Saturday mornings where he teaches a group of men from his church the chants and associated sistrum and dance motions for upcoming rituals. In this way, a larger group of participants are incorporated and important liturgical portions are inculcated as common knowledge. Moges has also published a set of CDs containing the complete chants for the annual cycle of holidays (Yä’amutu Wäräboch) and plans to record a DVD that will transmit his singing along with accompanying movements: “The DVD is very important to everybody. So at home you can follow it.”5

Moges Seyoum devotes extraordinary time and effort to maintaining the Ethiopian Orthodox liturgy in Washington, DC, despite holding down two full-time jobs. A similar situation exists in other American communities with much smaller Ethiopian immigrant populations; at the same time, these smaller communities can contribute to our understanding of the struggle to maintain Ethiopian liturgical and musical practices in these new environments. The Ethiopian diaspora community in Boston can provide additional insights.

Celebration of Masqal, the Festival of the True Cross, by members of three Boston-area Ethiopian Orthodox churches, in River Park, Cambridge, 2009. Photo by David Kaminsky

There are four Ethiopian Orthodox churches in the Boston metropolitan area, serving an Ethiopian community officially estimated at twelve thousand, but no doubt considerably larger. Of the qes (priests) serving these four congregations, only one, Qes Tsehai Birhanu, is also a highly trained liturgical musician. So extraordinary is Qes Tsehai’s story that I will recount it here in some detail.6

Tsehai Birhanu was born in rural Ethiopia. Orphaned by the time he was one, he was raised by his grandmother. There were many clergymen in his family and his great-uncle, a monk, trained him in liturgy from his early childhood years. After becoming a marigeta at the famed Qoma Fasilidas monastery in north central Ethiopia, Qes Tsehai received a diploma in Amharic literature from the Holy Trinity Theological College of Haile Selassie I University and also became an expert in performing improvised liturgical Ge‘ez poetry, qene. Qes Tsehai speaks with great reverence of the exhilaration he experiences from improvising qene: “When one does qene well, it is energizing spiritually.”7

Qes Tsehai Birhanu. Photo by Kay Kaufman Shelemay

In the early 1970s, after studying and teaching Bible and church music in the Ethiopian capital for several years, Qes Tsehai traveled to the Soviet Union, where, in 1975 in Leningrad, he completed a master’s degree in theology. After his return to Ethiopia, he served the church in several important administrative positions, including heading the church’s youth department. In 1982, Qes Tsehai left Ethiopia for the United States, to engage in postgraduate studies at Princeton Theological Seminary, and subsequently received asylum. He held several positions with the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in the United States over the ensuing years and, in 2001, moved to Boston following the invitation to serve as head priest and administrator of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Debre Selam Saint Michael Church in Mattapan, Massachusetts. In addition to his comprehensive musical, liturgical, and administrative skills and experience, a very special aspect of Qes Tsehai’s background made him particularly well suited to head congregations in smaller diaspora communities.

While a leading musician in the church in Addis Ababa in the late 1960s, before his departure for Russia, Qes Tsehai worked to engage the interest of urban Christian youths in Addis Ababa who were drifting away from the tradition. He composed strophic, unison hymns in Amharic, the Ethiopian national language. Qes Tsehai recalls vividly the process through which he invented a new genre of Ethiopian Christian choral music and issued the first publications of the genre:

Yes, the new style. . . . Let me explain to you. I composed this hymn book, while I was studying … [at] Holy Trinity College in Addis Ababa. I was assigned by the bishop to teach Bible and song at every church in Addis Ababa. At that time, [I was]. . . creating every new hymn. So I decided to. . . make a book of compositions. I sent it to the bishop. He just put his sign on it to be sent to the Department of Evangelization. They said, . . . “If it is published, it will be helpful for the younger generation of the church.” . . . And it was published. Soon everybody, even the bishops, the archbishops, the scholars, they had that book. . . . This was before I went to Russia. After I came back from Russia, they asked me to publish again. And that is why, now here in America, and throughout the world they are using my songs.8

Qes Tsehai’s hymns quickly became popular among young people in the church, and, during the revolution, when groups were forbidden to congregate, the songs provided an excuse for young people to gather in the church. The hymns, which came to be known as the “Sunday School Songs,” are today circulated and widely performed both in Ethiopia and worldwide. Circulated through cassettes, CDs, and oral tradition, these songs have opened a channel through which young people can participate in Ethiopian Christian liturgical performance. In smaller Ethiopian diaspora communities such as Boston, the choirs that sing these songs have both helped attract young people to church and provided ballast to traditional liturgical performance.

A woman plays the kabaro on Christmas at St. Mary’s Ethiopian Orthodox Church, January 6-7, 2011. Photo by Kay Kaufman Shelemay

The hymns also provided the first channel through which women of all ages could enter into the formerly all-male world of Ethiopian Orthodox liturgical performance. As Qes Tsehai noted: “Traditionally it is not allowed for women to sing. . . . But now it is coming. Even here, the women are participating with the men. Even in Ethiopia, in the cities they do.”9 Over time, women have begun playing the drum and the sistrum and have begun to acquire some basic knowledge of the traditional chant.

Today, choirs are heard at Ethiopian churches throughout the diaspora. At large churches, like St. Mary’s in Washington, DC, the choirs are large and coeducational. At smaller churches, in communities such as Boston, choirs tend to be comprised mainly of women and are small. The Amharic hymn texts are more accessible to the congregation than are the traditional chant texts in Ge‘ez, and many of the songs invoke the Virgin Mary. One of Qes Tsehai’s Sunday school songs, “A Voice Cried Out in the Wilderness,” is sung for the Ethiopian new year in September:

A voice cried out in the wilderness

Saying prepare the way of God.

If John told us his witness, let our heart be straight for our God.

CHORUS: O Virgin Mary, bless for us our New Year.

Thus, the perpetuation of musical and liturgical traditions from the Ethiopian homeland presents a great challenge in diaspora, with only the largest churches within major metropolitan areas having the musical leadership, let alone a sufficient number of musicians, to mount these rituals in full. Ritual performance in most Ethiopian American churches necessitates compromise in the face of constraints on personnel and time.

St. Mary’s Ethiopian Orthodox Church Choir, Washington, DC, January 27, 2011. Photo by Marilyn E. Heldman

Like Qes Tsehai, L. M. Moges also undertakes activities that are overtly innovative in the musical domain. He arranges liturgical portions to perform on special occasions and, in October 2007, arranged the chant, instrumental accompaniment, and dance for a presentation during the 69th National Folk Festival, in Richmond, Virginia. While most of his activities are in service of sustaining long-standing traditions, L. M. Moges devotes a great deal of time and attention to reshaping these materials for performance in new diaspora settings. He understands that the Ethiopian Church needs to reach out to a broader public: “In the American society, we have a plan, you know, to show everywhere. Not in our church only. We have to explain for people and, for example, universities. . . . There is the game of promotion.”10

Tsehai Birhanu and Moges Seyoum have expended decades of effort to reestablish the Ethiopian musical liturgy within the United States. Both have served their communities in exceptional ways and have received public acknowledgment. Qes Tsehai has received certificates of recognition from the United States Congress, from the Massachusetts State Senate, and from two Boston-area city councils. In September 2008, L. M. Moges received the National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship. On the day following the ceremony on Capital Hill and a festive banquet in the Great Hall of the Library of Congress, a celebratory concert for fellowship winners was mounted at the Strathmore Music Center in suburban Maryland. As part of an awards program that featured a Korean dancer, a Brazilian capoeira master and his troupe, a New Orleans jazz clarinetist and ensemble, and Oneida Indian hymn singers, L. M. Moges and ten musicians from St. Mary’s Church performed Ethiopian chants on the Strathmore stage. But, perhaps the most extraordinary moment followed the curtain calls, during which each fellowship winner took a final bow while the jazz band played choruses of “When the Saints Come Marching In.” When all the awardees had congregated on stage, and the band continued to play, the capoeira troupe suddenly and spontaneously began to perform traditional capoeira moves to the music; a few of the young men approached the older Oneida women and invited them to dance. The Korean dancer began dancing her own elegant style in the middle of the stage, and several Oneida couples started to dance the two-step. On the right-hand side of the stage, the Ethiopians, led by Moges Seyoum, stood in full liturgical dress. They looked at each other in amazement and then slowly joined in, swaying to the music and reinforcing the jazz band’s beat with the boom of the kabaros and the tinkle of the sistrums. On this evening, Ethiopian lives and liturgies were clearly very much at home in North America.

Notes:

- See Kay Kaufman Shelemay and Steven Kaplan, introduction to “Creating the Ethiopian Diaspora: Perspectives from Across the Disciplines,” special issue, Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 15, no. 2/3 (fall/winter 2006, published spring 2011): 191–213.

- Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vol. 2 (Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952), 159–160.

- Ethiopians are traditionally called by their first names. I thank L. M. Moges Seyoum for sharing details of his life story and musical activities with me.

- Moges Seyoum, interview by author, August 2, 2007.

- Ibid.

- I am grateful to Tsehai Birhanu for sharing his life story and musical knowledge with me over the last decade.

- Tsehai Birhanu, interview by author, April 12, 2008.

- Tsehai Birhanu, interview by author, September 17, 2010, and April 12, 2008.

- Ibid.

- Interview by author with Moges Seyoum, August 2, 2007.

Kay Kaufman Shelemay, the G. Gordon Watts Professor of Music and of African and African American Studies at Harvard University, is currently writing a book about musicians of Northeast Africa living in diaspora.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.