Featured

Crossing Rivers

A journey of spiritual companionship.

Cover illustration by Simon Pemberton. Cover design by Point Five Design.

By Eric Gutierrez

I remember this river. The river itself is not a very strong memory, but the idea of it stays vivid, how its stately flow carried local myth into my imagination, how it swept away the man I might have become. The first time I was faced with the myth of the Charles was the first time I came to Harvard as an undergraduate. Everything about Cambridge then felt foreign and I had looked forward to the Head of the Charles regatta like a tourist in a new landscape of culture and books and manners, with exotic customs like tailgate picnics, and with dangerous, glamorous natives in summer dresses, straw boaters, and grosgrain ribbon belts. I had even imagined myself as a tribal preppy on the riverbank, daring to masquerade in linen trousers and silk tie, cheering the Crimson crew as if I, too, had rowed downstream my entire life. I could almost hear the long oars slap the black water, cutting the current in long slices.

Instead, I worked that Saturday, like all Saturdays, as a handyman, searing generations of old paint with a blowtorch from Victorian moldings at a house on Oxford Street. On Sundays I worked as a waiter in the homes of various Harvard deans and masters, and on that Head of the Charles Sunday, wearing a too large nylon crimson jacket and a clip-on bow tie, I circulated trays of stuffed mushroom caps and Cape Cods to the crowd I had imagined, those pretty girls in sundresses and sporty collegians in linen trousers with grosgrain ribbon belts. The party guests had all just come from the river where they had cheered the rowers until they were as hoarse as coxswains. But the Charles flowed without me.

That was in September, long memories ago. In February, 20 years later, at Harvard Divinity School on a Burton Fellowship, I found myself one day sitting on a cold bench, snow beneath my boots, my breath escaping in clouds, watching the river I remember but never rowed.

Like me, it only appears to be still, its currents hidden below ice that is thick and convincing. Leaving my bench, the mud and snow are heavy-going and I make my way clumsily to the footbridge downstream. My eye follows the river bend to the horizon of bell towers and red brick, blue domes and iron gates, monuments of the exotic Northeastern erudition I waited on as a young man when I imagined myself belonging beside this cold river. The wind picks up, disturbing flurries of snow across the ice like old ideas.

I turn back to the bank where winter is still complete. I pull my collar up and my hat down. It is cold. The river, in the manner of winter rivers, pretends to rest. The ice shines hard, serene, as if forever. Just beneath, the black water asserts itself, like time.

I’m on the western bank. Looking east. This is where I ended up with God and life. I know my beliefs but I don’t know exactly how I got here. How did I get here? I search the river. I remember its flow. I remember my first, most constant spiritual companion, the one who walked with me and talked with me before I knew any god.

He taught me about the picking seasons, to recite the alphabet in Spanish, to argue my point, to honor my family. He taught me how to pray. All these lessons I forgot or disregarded on my way back to this river.

My grandfather crossed another river. The river he crossed—the Rio Grande—is wide, the current colored by silt and mud. The river I have come back to after 20 years—the Charles—is narrow and the color of the cold, deep sea.

Our story is the story of spiritual companionship, of crossing rivers, or maybe the same current but in two different directions. In this way his story and mine are the same strange tale, the one all men eventually tell themselves and tell their God. It is about how we ended up on different banks and how he saved me from drowning.

Saturdays, the Sabbath, I spend with my grandparents. They are 90 and 92 now, my grandfather unsteady on his feet and in need of a cane, my grandmother childlike and loving in the advanced stages of Alzheimer’s, and yet my grandfather insists they continue to live alone in the ranch house in the Los Angeles suburbs they bought almost 60 years ago. The backyard Eden with fig trees, papyrus, waterfalls, and koi ponds where I used to play is now overgrown; the ponds are empty. The pet shop on the corner has been replaced by a sex shop, and the nearby supermarket is abandoned and boarded up. The middleclass neighborhood of their dreams is tagged by gang graffiti and wrought-iron security bars defend open windows. They left the barrio two generations ago but the barrio followed them.

Although I left Harvard Divinity School in 2005 I never thought I would leave my life in the East. But I wanted to be part of this time of my grandparents’ lives, to be with them as they had been with me when as a child I needed them most. And so I spend Sabbath afternoons on the floral sectional in the cluttered living room, family photos and an army of figurines covering all available space. We watch the Seventh-Day Adventist satellite station, 3 Angels Broadcasting Network. I am still a child in many ways in this house, most often when I can’t help expressing my exasperation and disagreement with the television preachers. This living room is my grandfather’s church now, as he worships from the corner of the floral sofa along with the 3ABN pastors, but I have forgotten how to be reverent.

At first only two or three souls silently made their way down the center aisle to the lectern where Pastor Crispins stood, his soft high-pitched voice inviting forward all those who wanted to be saved this Sabbath morning, to give their love to Christ and live for him in the promise of everlasting life. Behind the lectern, a stained-glass Jesus smiled, a weak lamb cradled in his arms, his face inclined in a gesture of acceptance and invitation to the flock surrounding him. As the organ began a new, asthmatic verse of “How Great Thou Art” a few others left the hard wooden pews and moved toward the pastor’s promise and Jesus’ stained-glass embrace.

On my toes, I could barely see above the pew in front of where my family stood fanning themselves silently, reverently. Our Adventist church did not believe in loud music, air conditioning, or exclamations from the congregation. Everything was muted, the organ music, Pastor Crispins’s supplications, the whisk of church programs hushing the hot August air. We had come to the pink adobe church in Van Nuys as we came every Saturday since I could remember, to worship with modesty and reverence, to sweat or to shiver, to sing or (in my case) to nap.

As I watched a growing number of men and women deciding for Christ walk with heads bowed to the front of the church, the pianissimo hymn, the reedy tenor of Pastor Crispins, and the gentle glass Jesus worked something free in me. Something seemed to break loose and come clear: I was 6 years old and in love with Jesus. I was in love with Jesus and he loved me too and that was all that mattered. I didn’t care about everlasting life. I just wanted him to take me home, to heaven. I wanted him to come soon and to be held by him like the weak glass lamb. I wanted to be ready.

I looked along the length of the entire pew filled with my family, brushed and pressed and mascaraed, and pushed past my brother and into the aisle, following the music and the promise. Following Jesus.

Standing in front of the pulpit surrounded by adults in fellowship, in prayer, in this first sense of God’s love, so much like mother love in its completeness and familiarity, I was happy. I had never been an adventurous child, never even ventured around the block without someone’s trusted hand, and yet I eagerly joined the group of strangers in the line for heaven. We said “amen,” and when I opened my eyes I felt God’s hand, solid and gentle and warm on my back. I looked up and saw my grandfather smiling down at me with great, complete love.

I don’t know if my grandfather and I have ever been closer than we were the morning I was saved when I was 6. We have been as close many times but perhaps never closer. Of course I have been saved and lost many times since. My grandfather stayed saved, meaning he has remained satisfied in his relationship with God, and so never really had to join me in the pulpit call when I was 6 and in love with Jesus and working on my first stab at salvation. But he joined me anyway.

The following week he gave me an illustrated Bible, and I would gaze at Adam and Eve, as glamorous as movie stars in their fur tunics, faces buried in their hands with shame, racing from Eden. Adam’s bare, muscled torso was pale and hairless like my GI Joe doll. Behind him Eve tried to hide. The Tree of Knowledge sagged under the weight of its fruit. The Tree of Life was nowhere to be seen.

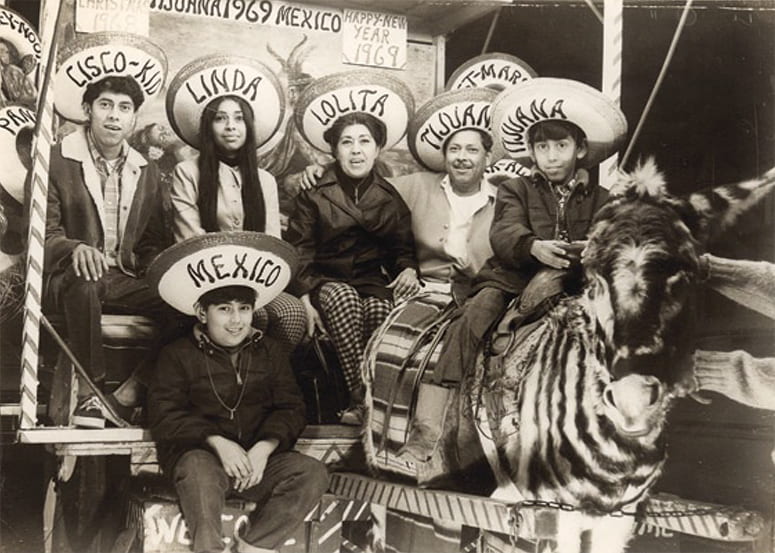

Photo courtesy Eric Gutierrez

Born on Christmas 1915, he was christened Manuel Garcia Moreno. It was not until my freshman year in college, during a choir rehearsal for a holiday concert of The Messiah, that I learned Emmanuel means “God with us.”

My grandfather and I had a hard time discussing our faith once I began taking God seriously. At first he had been excited when I told him I was entering divinity school, and in our phone conversations twice a week he wanted to hear everything about my studies. Soon it became clear that what I was learning puzzled him and what I was thinking scared him.

The differences in our understanding of faith became apparent when I returned to California from Harvard in the middle of my first year and sat in my grandparents’ kitchen trying to convince my grandfather that we needed to seriously consider how he was going to cope once my grandmother’s Alzheimer’s symptoms made it impossible for her to cooperate in her own self-care. “Did you come to visit or to cause trouble?” he asked me with the smile that meant it was time to change the subject. I was seriously concerned for their safety. Still, he was not ready to discuss her inevitable decline and the consequences we would all have to face.

The first time my grandmother, whom everyone calls Honey, fell, my grandfather did not call for help. Instead he struggled for 15minutes to get her off the floor, finally succeeding but not without exhausting them both. The second time she fell he, too, lost his balance and they ended up on their bedroom floor laughing at their predicament with tears in their eyes. When my brother also tried to get him to consider the need for an outside caregiver, explaining that if either of them should fall again someone should be there to help them up, he responded, “The Lord will pick us up.”

I was frustrated. It seemed as if our family needed help, but to talk about it became the problem, not the problems themselves. Faith, rather than giving us the guidance and strength to discern and act on what needed to be done, instead became the junk closet where we hid away whatever was messy, broken, and embarrassing from the outside world, from ourselves and each other, even from God. The challenges and promises of both faith and life didn’t seem to be honestly engaged but, rather, continually deferred and unspoken.

Honey’s Alzheimer’s, my parents’ finances, my uncle’s drinking, my aunt’s increasing social isolation, my and my brother’s gayness, all these questions and uncomfortable truths beset us and challenged our preferred identities. They insisted we rise above our previously comforting yet ultimately inadequate understandings of family and faith and ourselves. Clearly, we were being called, as all families are called, all faithful sons and daughters, to seek answers, to learn from the past in order to heal the present and create our future.

When I was a teenager, I began to think my family’s religion was inadequate, our prayers too small and misdirected to be of much help. Instead of asking God to heal the habits of mind and heart that limited our lives and spiritual growth, we seemed to settle for little more than forbearance. We asked little more of God than to endure life with as few heartbreaks and obstacles as possible, rather than asking for the sight to rejoice in our creation and the wisdom to take care of our blessings. We failed to trust God enough to risk changing, to risk doing and seeing things differently. Our church, I believed, had encouraged us to see ourselves as a family of sinners instead of disciples. And so our sin, our sicknesses, our shortcomings, became our lives.

Of course this was denied. On Sabbath mornings in church we claimed to be joyful in the Lord, and greeted others with broad smiles, chirping, “Happy Sabbath!” But in our lives something had happened. The ideas of James Dobson rather than Jesus Christ became the context for our understanding of God and life. We lived in fear rather than faith. Fear of poverty, fear of crime, fear of damnation, fear of honesty. Religion became the sugar coating covering the stagnation in our personal lives. The underlying truths, rather than being addressed in faith, were assumed to be no longer valid. Baptism and the assumption of salvation had given us new life, we insisted. But the old life situations and focus remained. Only now we believed we no longer needed to address them since they were no longer our responsibility. Now our lives were left in God’s hands. God was going to pay our debts, provide necessary medical attention, pick us off the floor when we fell, keep us sober, make our marriage last. God would provide. We didn’t have to do a thing.

Years later, sitting in my grandparents’ kitchen in California, I felt shadowed by the nature of my childhood faith, just as my grandparents had been followed by the barrio they believed they had left behind for good. I was no longer embarrassed by faith, finding any talk about God beyond a generic ”spirituality” an extreme form of bad taste, but I was no longer in love with the stained-glass Jesus.

I could not help still thinking we had mistaken faith in God for irresponsibility about our commitments and obligations to life. If our lives are expressions of our faith, then we must live them. To passively await the sweet by-and-by, I had come to believe, meant living in spiritual complacency, if not outright fantasy and delusion. We are not in relationship with God when we fail to ask and answer for ourselves what it means to follow in Jesus’ footsteps, not in the afterlife but in the here and now, and then to start walking.

If faith is anything more than hope in a promise, it is because it is the source of palpable transformation. The topography of our spiritual journey is reflected in the shifting terrain of our lives. Profound shifts in our lives, hearts, and circumstances are not the result of intellectual understanding, psychological insight, or emotional awareness. We can acknowledge, accept, and analyze why we are the way we are, yet remain powerless to change. It is only through spiritual willingness to see and do things differently that we can transform and heal who we have become and what we must face. Of course, following Jesus means so much more than that, but it means nothing less. Creating heaven on earth is hard work.

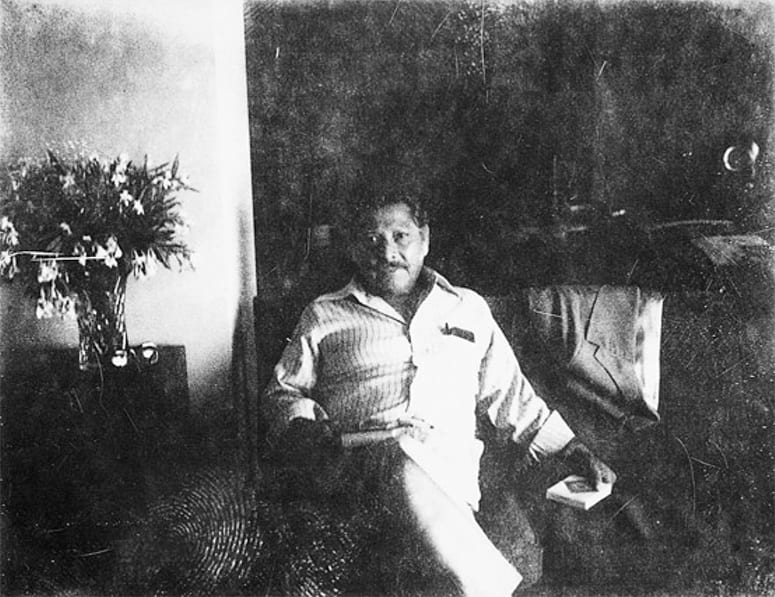

Photo courtesy Eric Gutierrez

In my final year back in Cambridge, two weeks before Christmas, my grandfather’s 89th birthday, the phone rang. “I see you as Paul when he was Saul,” my grandfather called long distance to tell me. “You’re attacking everything I stand for and believe in, the religion of my parents and the religion of your parents.”

I was stunned into silence. Since beginning my theological studies I had shared with him the questions I encountered, the alternative interpretations, the revelations of history, theology, and biblical scholarship. I wanted my grandfather as my spiritual companion. I trusted his faith if not his religion. I always had. But he did not trust mine. At least not anymore.

When I was 6 years old, in love with a stained-glass Jesus, he had watched over me as I made my way up the aisle to salvation at our Adventist church. Then he had followed me up to the pulpit because he had walked that way before and believed he knew where it led. But my faith journey was now taking me where he had never been and could not follow. I was troubled that he could see my personal relationship with God as an attack on him and his relationship with God. I felt he was judging me, that in his eyes I either had to understand as he understood or I was mistaken—no, more. My grandfather had called me Saul, had told me I was the enemy.

It took me time to admit how angry and hurt I was. Although I knew I could not betray my own faith journey for his sake, I needed him to know how much I respected him and saw his faith not as flawed or wrong but as simply that, his faith, one that put him in complete harmony with God and fully delivered him into life. I did not like disappointing him. I missed our relationship as it had been when I was a boy, everything as simple and unquestioned as life in Eden. But my faith in God did not allow me to pretend. God, I had come to believe, demands more.

Perhaps we had never been spiritual companions in his eyes at all. Certainly I had always learned from him and had more to learn from him than he did from me. But this refusal to consider how God might give us to understand ourselves and our lives and, therefore, his will differently felt like a personal rebuke, an ugly epithet spat at me in the street. My grandfather had never been a tyrant in any aspect of his life, yet now he demanded I accept his truth as the only one and mine as delusion and lies. The way he understands God and the imperatives of faith aren’t open for interpretation. We are to take his religious, scriptural, and self-understanding at face value. That I could not, upset him deeply. He lost sleep. He worried for my soul.

He has settled his faith and made his choices. To see things otherwise is to again ask the questions he has already answered with his life. He has found comfort and refuge and redemption. His life challenges have been resolved by his particular relationship to God. If mine are not, his attitude suggests, if I need to look further than his view of faith for my own, then I clearly have not looked closely enough, clearly I do not understand.

Holding the telephone in my Somerville flat, I knew there was something genuine and entirely accurate about what he said. We cannot understand fully or profoundly the way God gives another to see the world or him. I cannot be entirely accurate in knowing or giving voice to my grandfather’s faith and life. In significant ways, that is not my job. It is his alone. But it is my responsibility to learn from him all I can while endeavoring to discover my own way, to live my own faith and life.

On the phone, I explained to my grandfather that I did not want to attack his faith, but rather to explore my own. I told him that for me it is only faith if it endures and grows after being tested. Otherwise what we often call faith is little more than comforting bromides and cultural conformity. Faith cannot be inherited the way religion can. Rather, it is the encounter of our very being with God. I was born and raised as an Adventist. I had to become a Christian on my own.

Finally his voice cracked. He could no longer talk. When we hung up, we both felt attacked and misunderstood.

Photo courtesy Eric Gutierrez

A few weeks after that telephone conversation, I return to California for my grandfather’s 89th birthday. A strand of colored lights twinkle on the small, fake Christmas tree. We are alone in my grandfather’s living room, it is quiet, and we are careful to be gentle with each other. I take his hand. I ask him what it means to love one’s neighbor. He tells me about salvation, about accepting Jesus as savior, about following the Bible as the literal word of God. He explains that we are to love our neighbor by correcting him when he veers from the Christian path, and through such instruction lead him to salvation. I ask him to tell me how he knows which is the right Christian path and he laughs. “I thought you were studying the Bible all this time at Harvard,” he taunts. “It’s all in there, crystal clear.”

But it isn’t crystal clear, I tell him, not to me or to millions of well-intentioned Christians of differing denominations and creeds who study the Bible for guidance, who have greater wisdom and knowledge than I have. I explain to him that when I read the biblical accounts of Jesus’ life and teaching I see concrete examples and instructions as to what constitutes godly loving and living. They may be contested but this is where Christians must start, I say, with Jesus. My grandfather warns me against alternative readings of the gospels, about misguided faith and false prophets. Almost in unison we reach for the same verse from the book of Matthew, me in riposte, him in defense: “By their fruits you will know them.” He smiles sadly.

I tell my grandfather I am troubled by the way so many American Christians, including Adventists, focus almost exclusively on salvation through faith in Christ and on the implications of his death while virtually ignoring the lessons of Jesus and the implications of his life. Salvation, I say to his obvious shock, is a dire distraction from the real work of Christian life. I am confused by how much this upsets him. After all, as most Protestants will acknowledge, we have no control over salvation. We cannot earn it. The Reformation was supposed to have ended that discussion. We cannot believe our way into eternal life. Faith is fallible. Jesus was clear on this point. Many claiming to act in his name are strangers to his word. Rather, as the New Testament stresses, “We believe it is through the grace of our lord Jesus that we are saved” (Acts 15:11).

So what is the purpose, I ask him, of misleading so many into focusing their spiritual life on something that is quite frankly out of their hands and none of their business? Salvation is “not from yourselves, it is the gift of God” (Ephesians 2:8) alone. We cannot decide to be saved, despite what so many now claim. We can only decide to follow Jesus, I conclude, and pray for the strength, the wisdom, and the courage to discern what that means and then work toward where that leads in the world today. “Oh, Eric,” my grandfather moans as if in physical pain, “Christ died for your sins, he died to save you. How can you not care about that?”

My voice fails me and I can barely contain my sadness. His voice is hoarse. Our time is short. We will not be talking like this for very much longer. Our worlds have parted and the world to come is uncertain. Soon I will be returning to Massachusetts, to gray skies, final exams, and subfreezing temperatures. Soon we must say good-bye.

And so again I cannot help raising my voice in frustration and urgency and fear of losing him. I tell him no, that Jesus did not die so that we may fixate on sin, not ours or anyone else’s, but so that we may love one another more perfectly and live. No, I tell him, loving our neighbor doesn’t mean coercing him into adopting our faith or substituting personal spiritual willingness for someone else’s religious zeal. Jesus admonished those who concern themselves with the speck in another’s eye while ignoring the beam in their own, I say too loudly. Isn’t it possible, just possible, I ask, that in our zeal and genuine desire to share the gifts of our faith, the old rugged cross has become the beam in our own eye?

The lights on the Christmas tree flash weakly. The room is filling with shadows and the smell of holiday tamales. I can’t bring myself to look at my first spiritual companion, can’t bear to disappoint or upset him again. The silence is too tender.

“I couldn’t agree more,” my grandfather says finally, his gravel voice soft yet strong. I am stunned, as speechless as when he called to tell me I was Saul persecuting Christians. “I want you to talk to me more before you go,” he says, so much calmer now. “We can study together.”

Sometimes, as we sit together each Sabbath, I will read the Bible to him while my grandmother naps. Or he will tell a story from biblical or family lore and I am humbled to realize how many lessons my grandfather has yet to teach me. Or we will hash over the sermons of the 3ABN preachers. At times we become excited or exasperated, but for me it feels as if together we come alive in faith. At times I fear I have angered him. However, on the days he does not accuse me of missing the point, he tells me I should become a preacher. On the days I do not interrupt, I thank him for showing me the way. Talking like this about God with my grandfather is how I worship now. This is how I keep the Sabbath day.

Since I was 6 years old my grandfather has been my truest spiritual companion. We have argued and misunderstood and made great assumptions about the nature of one another’s life and faith. But we have also kept talking. We didn’t give up. Our lifelong dialogue has taught me that our most essential spiritual companions are not those who necessarily share our faith but, rather, those who take our faith seriously and do us the honor of sharing their own honestly.

While I was still in Cambridge my grandfather and I would often talk until he had grown hoarse, barely able to speak, or I was late for work or had missed a lecture. Once, when we were heatedly discussing God and the world, long distance, my mother picked up an extension in California and interrupted. “Enough,”‘ she announced. “No more fighting.”

“We’re not fighting,” I protested.

“Yes,” my grandfather agreed in his raspy voice. “We’re studying.”

What it means to be a faithful son or daughter has never been as self-evident as some now claim. Faith cannot be inherited, just as identity cannot be dictated. I was a Christian like my grandfather, then I was not. I was a Mexican like him, then I was not. I had to leave him and all he believed to find my own relationship with God, to find my own way of walking in the world and of being a man. That is why every faithful son or daughter is invariably a prodigal, one who must inevitably cross his or her own river. No one else can do it for them. But if they are blessed, someone is praying for them to cross safely and reach the other side.

I had been away from the Charles for so long. I returned to search the current, to remember the way it felt, how easy and then how hard it was to believe. Twenty years after I first said good-bye to this river I left it again, returning to California and a legacy of faith. My reflection was not in that river. I am the reflection now, the shimmer and spark of other lives and the breath of God, of those who taught me how to pray and to worship with my life.

My grandfather worships every day. All these years, all his labors and our conversations on Sabbath afternoons have been his prayer for me, for his family, for all of us struggling in deep currents. He sleeps late now, until 7 am, rising to take care of his wife of 65 years. He makes her breakfast, mostly huevos a la mexicana, gets her out of bed, and leads her to the table. She opens her mouth to receive the meds he has arranged beside her plate, a daily devotion he presides over. He bows his head and says a silent grace. Then they eat.

Eric Gutierrez, AB ’84, MDiv ’05, teaches courses on religion, public theology, and cultural conflict at the California Institute of the Arts. His commentaries have appeared internationally. His new book, Disciples of the Street: The Promise of a Hip-Hop Church, will be published in March 2008 by Seabury Books.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.