In Review

Ethics and Vulnerability in Watchmen

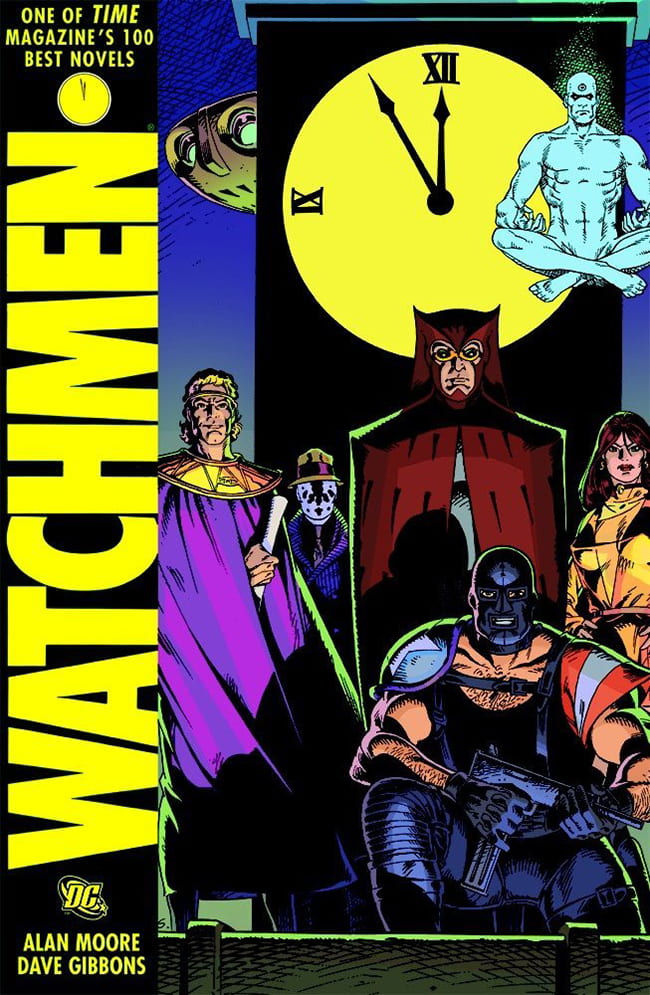

Art by Dave Gibbons; Copyright DC Comics

By Jonathan Schofer

Watchmen is considered one of the great comics of the twentieth century. Created by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, it has generated, and continues to generate, a deep reconsideration of the superhero and a large following. Watchmen appeared in 1986-87 as a series of 12 comic books and was soon gathered into a graphic novel of 12 chapters. Recently it came out in theaters as a feature film and received mixed reviews, but also raised the profile of the work. I would like to introduce and reflect on the story from a particular angle, a set of problems that I care deeply about: the significance of physical and psychological vulnerability for ethics.

Ethical theory today struggles to address the lived realities of the ethical life, the possibilities and limitations of embodied action in the world. In recent decades ethicists have increasingly emphasized that ethical theory cannot presume a continually free, autonomous, healthy, strong agent who encounters weak, needy others. Rather, all people are susceptible to harm, and ethical theories are distorted when they ignore the fragilities of a person engaging in contemplation and action. Vulnerability has many dimensions, including physical and emotional. Perhaps most striking, the very bases for ethical claims, and the possibilities of attaining ethical ideals, may themselves be fragile and susceptible to harm.

Ethics and vulnerability interweave in many ways. Foregrounding vulnerability may mean giving great weight to how individuals and institutions should treat the young, the old, the sick, and the disabled—for each person was, is, or probably will be in those states. Or, when we consider how we should treat others, we should emphasize that persecution, warfare, and environmental destruction are possible for all and actual for many. More subtle issues surround the fragility of our own ethical ideals and practices. Do we have theoretical grounds to support our ethical ideals? In practice, are we able to fulfill those ideals in ways that are truly good? Does the goal of right action enable us to flourish, or injure us?

The world wounds the persons and plans of those who try to act well, yet we find no alternative but to keep trying.

Vulnerability pervades Watchmen. World war and nuclear annihilation permeate the background. Grotesque, vivid violence permeates the foreground. Blood. Guts. Pain. Perversity. The world wounds the persons and plans of those who try to act well, yet we find no alternative but to keep trying. Conspiracy schemes and hidden plots are everywhere. Those who ignore them appear naïve, yet those who search them out seem crazy. In the process of inquiry, they hurt others, they may hurt themselves, and their very inquiry may further the scheme itself.

Watchmen is a comic about comics, whose greatest strength may be its exploration of the medium itself. A comic book provides relatively minimal stimulation compared with film, and the drawings of Watchmen show great control. Precise images on a nine-square grid cover each page. Each square is exactly the same size. Moore and Gibbons push the possibilities of the comic medium quite far. Time and perspective shift quickly from frame to frame. In some cases, subsequent frames alternate between dates, or interweave two scenes or stories. The words of one narrative may appear with images of another, indicating that the two stories gloss one another. Sequences have tight transitions, where the words that end one begin another.

These formal features convey several ideas about time, narrative, and the self. The story states explicitly that the past and the future all exist but can only be seen by superhuman beings. For one who can see all, the temporal shifts are quite natural. Closer to our experience, Watchmen conveys that human memory condenses time. Our minds can erase historical sequence, grouping images by theme and emotional memory such that other patterns arise. Both of these points are well developed in the film, but a third is largely covered over: a common theme in Moore’s work is that narratives have significant causal impacts upon our lives. We not only tell narratives but discover them and live them out. The interlacing of narratives in Watchmen shows multiple characters to be enacting variations of the same story. The primary story told over and over is that a man goes to extraordinary lengths to save what is most dear to him, and in the process he loses his own capacity to act with justice and love.

The most explicit statement of this theme is in a comic-within-the-comic, a pirate story titled “Marooned” that was omitted from the film, but apparently will be released on the DVD. Watchmen presents a world with real costumed heroes and people reading comic books about pirates. We read “Marooned” over the shoulders of a young man sitting by a newsstand while his mother is working. A horrific story portrays a man who has survived a pirate attack, does everything he can to save his family, and in the end becomes the evil he hoped to stave off. The details are fascinating and gory, winding their way to the man’s question: “How had I reached this appalling position, with love, only love, as my guide?” Characters in Watchmen have many guides—love, ambition, insecurity—but those who espouse lofty ideals end up in some version of an appalling position (a contrast to this pattern is Bernard the news vendor—watch his growth closely if you read the book).

The main plot of Watchmen takes place over the course of three weeks, from the murder of Edward Blake on October 12, 1985, until the night of November 2, with a brief follow-up on Christmas Day. Through flashbacks and other subnarratives, the story ranges much more widely. Soon after comic book publishers create the figure of Superman in 1938, people begin to dress up in costume and independently fight against crime. A year later, a group of these aspiring superheroes gathers as the Minutemen. All are ordinary and flawed human beings, though they train hard and some gain extraordinary abilities—the most prominent Minuteman in the plot is Blake, known as the Comedian. They work together for a decade before disbanding. After the Minutemen dissolve, one truly superhuman creature emerges. In August 1959 Jonathan Osterman, a young physicist, is caught in an experimental test chamber and seems to die. Over the course of the next few months, he reappears with great physical, intellectual, and perceptual powers. Soon Osterman takes on a significant role in world politics working for the United States as Dr. Manhattan.

In 1966 another group forms, inspired by the Minutemen, and they call themselves Crime Busters. These characters take center stage in Watchmen, particularly Walter Kovacs (Rorschach), Daniel Dreiberg (Nite Owl), Adrian Veidt (Ozymandias), and Laurie Juspeczyk (Silk Spectre). Crime Busters operates until 1977, when their independent battles inspire a strike by the New York police, riots in the streets, and then a legal act that prohibits vigilantes. Most of the Crime Busters retire their costumes. The Comedian goes to work for the government along with Dr. Manhattan. Rorschach refuses to stop, however, leaving a dead rapist at the door of a police station with a piece of paper on his chest saying, “neveR.” When the Comedian is killed in 1985, at the same time as nuclear tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union reach a critical point, the retired heroes slowly gather, recall their histories, and become embroiled in an adventure that may end with the destruction of humanity.

Throughout their activities, the Minutemen and Crime Busters find evil difficult to identify and defeat. They know pulp adventure fiction and comic books that present “absolute values where what was good was never in the slightest doubt and where what was evil inevitably suffered some fitting punishment.” By contrast, their human world is messy and inconsistent. The aspiring heroes first take on ordinary criminals and then costumed enemies. Things get more complicated when they need to address organized crime, and all the more so when they see their obstacles as linked with the cultural changes of the 1950s and 1960s (“promiscuity, drugs, campus subversion”), the cold war and nuclear threat, and environmental destruction.

The costumed heroes show a wide span of political views and impact. The presence of Dr. Manhattan enables the United States to win the Vietnam War, and Nixon remains president for multiple terms. The Comedian probably killed Woodward and Bernstein, and possibly also Kennedy (the movie makes this assassination explicit). Both the Comedian and Rorschach are compared to Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan. Ozymandias, by contrast, leans to the left and criticizes his fellows on the right. Watchmen ultimately criticizes heroic projects on all sides. The title emphasizes suspicion of people claiming high ideals, and the epigraph quotes the epigraph of the Tower Commission report:

Quis custodiet ipsos custodes. (“Who watches the Watchmen?”) Juvenal, Satires VI, 347, quoted as the epigraph of the Tower Commission Report, 1987.

Moore and Gibbons probably direct our attention more to the real world politics of the 1980s than to the first two centuries CE. The quotation contrasts with John F. Kennedy’s famous expression, “Watchmen on the walls of world freedom.” What are the boundaries and limits of those who claim to guard others’ freedom? Watchmen presses this question over and over again, and the words, “Who watches the watchmen?” appear throughout the book as graffiti. Perhaps most poignant is a small detail. One frame presents Rorschach right after he has beaten up a man, and on the alley wall we see in spray paint, “Who watches the wa. . . .”

Along with ambivalent politics, the heroes display flawed ethical sensibilities. The Comedian and Rorschach immerse themselves in the horror and pain of life. From burning a murderer who dismembers his victim and gives the bones to his dogs, to burning Vietnamese villages, these men dive into the violence. Rorschach in particular sees life as meaningless, with “no meaning save what we choose to impose.” His response is to “scrawl” his own design on a “morally blank world” and to impose an uncompromising picture: “There is good and there is evil, and evil must be punished.” An independent vigilante with no sense of due process, Rorschach inspires terror among those in bars and alleys. He has a penchant for breaking people’s fingers. In many ways he is the most disturbing of the heroes. Rorschach is also the closest that Watchmen has to a central figure and, on the gravest moral issue of the book, his judgment may be right.

The medium enables Watchmen to link the story of personal destruction in “Marooned,” the comic-within-the-comic, with the story of Malcolm and Gloria.

Other characters are highly intellectual. Seeking an objective standpoint from which to act, they lack ethically significant emotional responses. They fail to have compassion for individuals, for particular humans, because they are immersed in some version of a big picture. Ozymandias is the smartest person on earth and believes that intelligence will solve all problems. This outlook ultimately leads him to take on a disturbing utilitarian stance. He is willing to kill masses of people based on the calculation that he would save many more. Dr. Manhattan can solve complicated problems in physics, dismantle weapons without lifting a hand, travel between planets, and know what will happen in the future. Yet he also grows more and more distant from human needs. He forgets that humans must breathe. He sees life and death as “unquantifiable abstracts.” Dr. Manhattan’s inhumanity is most vivid in a story of the Comedian, which the film portrays effectively. During the Vietnam War the Comedian has a romance with a Vietnamese woman who becomes pregnant. He leaves her, she finds him and strikes him, and the Comedian shoots her. In this moment of cold harsh violence, the Comedian sees that Dr. Manhattan had the power to stop the bullet and the murder, but did not. He accuses: “You’re drifting out of touch.”

Daniel Dreiberg and Laurie Juspeczyk are wounded, undirected, alone or in unsatisfying relationships, and do not know what to do with themselves. Both of these figures, though, bring out the humanity in others. More generally they represent balanced emotion and reason, caution and action. Over the course of Watchmen Daniel and Laurie grow and strengthen, yet in the end their prudence may reflect dangerous tendencies in ethical reasoning. They think themselves into complicity with atrocity, for inaction appears to be the best option.

Nothing in Watchmen undermines subtle philosophical theories of ethics, but through these characters we repeatedly see ethical ideals invoked to justify and often sincerely motivate deeply problematic action. Watchmen explores many other limits to the ethical life, in body and psyche. The heroes age, gain weight, and lose their strength. Some express doubts and regrets. Daniel comments, for example, that attempting to be a superhero is “a schoolkid’s fantasy that got out of hand.” He also describes a protective piece of equipment that broke his arm, and Laurie comments, “Jesus. That sounds like the sort of costume that could really mess you up.” Daniel replies, “Is there any other sort?”

Costumes mess up their psyches. Perhaps most complicated is Rorschach. Emerging from a horrible childhood hating his mother, at age 16 he starts working in the garment industry: “Job bearable but unpleasant. Had to handle female clothing.” A young Italian woman ordered a complicated dress: “Viscous fluids between two layers latex, heat and pressure sensitive. . . . Black and white moving changing shape . . . but not mixing. No gray.” The woman said the dress looked ugly and did not collect the order, so Rorschach took the dress home and cut the fabric so “it didn’t look like a woman anymore.” Two years later he learns that she was raped, tortured, and killed outside her own apartment, while the neighbors looked on. He then takes the remains of the dress “and made a face that [he] could bear to look at in the mirror.” Repressed desire, revulsion, aggression, misogyny, horror, and vengeance all intertwine with a deep search for humanity in Rorschach’s costumed face (the film does not explain the origin of Rorschach’s mask but still does an amazing job of portraying the fabric).

Watchmen explores not only the weakness of those in costume, but also ways that the world can uproot anyone acting with good intentions. I find this theme best developed through a minor character who is all but omitted in the film. Rorschach (Walter Kovacs) is imprisoned, and psychiatrist Malcolm Long takes on the case. Malcolm has a cheerful disposition, an apparently happy marriage with his wife, Gloria, and describes himself as fat and contented. He is also ambitious, hoping to gain a sense of the “syndrome” that leads to masked vigilante activities, and plans to “keep notes with an eye to future publication.” The dynamics of race and class are complicated. Malcolm Long is a successful African American doctor. Walter Kovacs is a white red-haired son of a prostitute. Kovacs looks down on Malcolm, accusing him of being fat and wealthy, of not understanding pain, and of seeking prestige under the guise of helping. Malcolm’s assessment of the situation is: “It’s as if continual contact with society’s grim elements has shaped him into something grimmer, something even worse. If only I could convince him that life isn’t like that, that the world isn’t like that. I’m positive it isn’t.”

The doctor becomes increasingly preoccupied with Kovacs’s case, staying up late, ignoring his wife, and ultimately becoming unable to socialize without bringing the horrors of Kovacs’s life into his own. After Gloria walks out on him, he looks at his own Rorschach blots, hoping to find a spreading tree. He first sees a dead cat and then the real horror: “In the end, it is simply a picture of empty meaningless blackness. We are alone. There is nothing else.” Things don’t end there. Malcolm resigns, and Gloria finds him on the sidewalk just as a fight breaks out down the street. She tries to say that she will consider coming back, if he will work with less demanding patients. Malcolm sees the fight and goes to help: “It’s all we can do, try to heal each other. It’s all that means anything. . . . Please, please understand.” She is enraged: “I’m warning you! You let yourself get drawn towards another heap of somebody else’s grief, I don’t want to see you again!” As he leaves, he says with apology, “It’s the world . . . I can’t run from it.” Is Malcolm a true hero, doing his best to help others in a modest, sincere manner? Or is he a true victim, driven by a mix of ambition and compassion to try to make a difference in an indifferent world while neglecting the intimate relations whose emotional vitality he needs? Malcolm, like Rorschach, ultimately chooses to scrawl his own design on a morally blank world, and, like Rorschach, he winds up isolated.

The characters and events of Watchmen are extreme and exaggerated, but the issues are real for many of us. The story addresses challenges brought by living with ethical ideals, by trying to maintain a robust sense of good and its relation to bad or evil. Watchmen reminds us over and over that attempts to act well are easily susceptible to deformations that damage others as well as ourselves: in fact, the grander our attempts at goodness, the greater the risks of destruction. This awareness does not legitimate inaction or withdrawal. Rather, the failed attempts at heroism point toward the need for humble engagement with others in support of what we can best assess to be good. At the end of the story, great destruction in fact occurs, carried out to further an ethical and political goal whose results are unpredictable and unstable. The central figures wind up dead, gone, alone, or in disguise. One character is perceptive enough or disturbed enough to ask: “I did the right thing, didn’t I?”

Jonathan Schofer is Associate Professor of Comparative Ethics at Harvard Divinity School. His research and teaching center on the ethics of virtue and character. His current book is a study of classical Jewish Rabbinic ethics titled Confronting Vulnerability (forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press). The author would like to thank Jeff Dean, Brett Rogers, Maura Kelly, Anne Monius, and Ada Brunstein for their comments and suggestions.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.