Dialogue

A Protestant Poet’s Theology of Sound

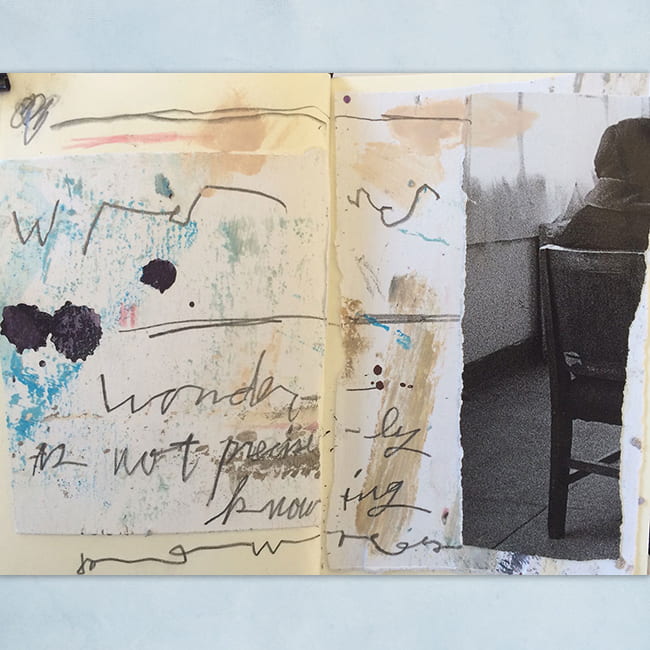

“Wonder—is not precisely knowing . . .” by Emily Dickinson, from Sketchbook, by Jane Cornwell via Flickr. CC BY-ND 2.0

By Nate Klug

In the composition of a poem, sound comes first. A pattern of words descends, and I’m off, or caught, or begot.

Sound is generative but soon hidden in the meanings it generates. In this way, sound resembles light, as it unfolds across the first chapter of Genesis.

Though accompanied by significant pleasure, this feeling of beginning a poem, more like listening than speaking, can also disconcert. “Something startles me where I thought I was safest,” reads the first line of Walt Whitman’s “This Compost.”

Adorning me with its demands, sound precedes what ideas I thought I possessed, what truths I knew I knew.

A fresh pattern shows up one day, like a charismatic prophet in the mind’s town square. Morphemes and phonemes bristling, jockeying against each other, “wanting to go on,” as Gertrude Stein said, sound promises a poem in exchange for my obedience, no questions asked.

Each time a string of sounds arrives, it keeps alive Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ridiculous question: “Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe?”

But my designs on originality cannot last forever. Most poems last not long at all. The nature of my faith in sound is inherently short-lived. Then silence, like a stone in the mouth—and then what?

There must be some link between poetry and grace, I tell myself, some shared identity between these occasional gifts of sound and God.

In the past, poets formulated viable connections between the experience of “present mercy” in the act of writing poetry and the “future mercy” that Christian doctrine promised. John Donne preached to his congregation at St. Paul’s “that all the way to heaven is heaven.” “A sight of happiness is happiness,” Thomas Traherne avowed in Centuries of Meditation.

But the radical Protestant tradition to which I subscribe suspects any attempt to tie God’s presence insolvably to earthly things. Idolatry is the replacement of God with what we can better understand, grasp onto—whether money, or bread and wine, or language itself.

In Philosophical Fragments, Søren Kierkegaard admitted that “at the very bottom of devoutness there lurks the capricious arbitrariness that knows itself has produced the god.” Although he wasn’t a poet, Kierke-gaard intuited the authority of the creative impulse and how, in its wake, faith and idolatry could feel identical.

For it becomes impossible to tell What is producing What.

On the other hand, there are no two better words to describe the way sound comes to me in a poem than Kierkegaard’s capricious and arbitrary. Random, mischievous, lurking somewhere above or deep beneath, on their arrival poetic sounds might slyly claim the excuse of John Milton’s fallen angels: “We know no time when we were not as now; / Know none before us, self-begot, self-rais’d / By our own quick’ning power.”

Three or four words exactly juxtaposed radiate an energy that belies all prior creations—and all prior creators.

As a poet who is also a pastor, or as a pastor who is also a poet, my vocations can seem complementary. I am involved with someone else’s words, in one way or another, all week.

But, just as often, I feel at the mercy of competing powers, a tension lively, if lonely, in its alternating pressures and torques. At those times, it helps to remember the productive conundrum of Emily Dickinson, especially her words from a late letter: “I work to drive the awe away, yet awe impels the work.”

For Dickinson, sonic visitations were far more relentless and consuming. She must have heard anagrams and off rhymes everywhere. “An Omen in the Bone.” “Denominated morn.” “The Lover – hovered – o’er.”

Sound impelled her poetry, a fact she acknowledged both literally—”I heard a fly buzz”—and metaphorically—”He fumbles at your soul / As players at the keys.” And in Dickinson’s inspired moments, the very nature of existence was phonetic: “And Being but an Ear.”

Can we say, then, that sound mediated God for Dickinson? That—as many people today seem eager to assert about themselves—poetry was her prayer?

Not so fast. Dickinson did explicitly compare God with sonic complexity in metaphors such as this one:

The Brain is just the weight of God –

For – Heft them – Pound for Pound –

And they will differ – if they do –

As Syllable from Sound –

But Dickinson’s temperament was much closer to Søren Kierkegaard’s than that of her Massachusetts neighbor, Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson envisioned a new church, revitalized, led by the artists of America. He shared Whitman’s view that literature could “drop in the earth the germs of a greater religion.”

Poetry planted a different germ for Dickinson, one that set her less at ease. “I heard of a thing called ‘Redemption’—which rested men and women,” she wrote in another of her letters. “You remember I asked you for it—you gave me something else.”

Are poetic sounds gifts from God? At times, Dickinson’s poems suggest the very opposite:

The Absolute – removed –

The Relative away –

That I unto Himself adjust

My slow idolatry –

The “undermining feet” of her vocation hindered Dickinson’s capacity for belief. What must have felt utterly wrenching resulted in her finest art. Her elegy for George Eliot pins her own soul to the wall as well: “the gift of belief which her greatness denied her.”

A pattern of words descends, and I’m off, or caught, or begot. And later, if I’m lucky, the poem can end, click shut.

As Dickinson puts it, the pursuit of sound points “Beyond the dip of Bell.” Sound leads beyond the circumference of sound—and, therefore, beyond the circumference of poetry itself.

Beyond the dip of Bell, I know I can do no more. Sound has no more to do with me.

It is at this point, she writes, that “I and silence” form “some strange race.” “Wrecked,” no surprise. And “solitary” as ever. But “here,” she attests. Here, here.

This location, this precision of thought and feeling, is the closest thing to a heaven in Dickinson’s work.

Which begs one final question: if God does host Emily Dickinson, if—as she never stopped imagining—she did reach heaven, do poetry’s sounds continue to visit her there? Does God finagle some ultimate reconciliation of powers, some merging of the light of great art with God’s own splendor?

Or does she wander, saved but never quite herself, her poetry extinguished by grace and remembered only as a kind of phantom limb?

I should have been too saved – I see –

Too rescued – Fear too dim to me

Nate Klug is the author of Rude Woods (The Song Cave, 2013), his versions of Virgil’s Eclogues, and of a book of poems, Anyone (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming 2015). A minister in the United Church of Christ, he has served congregations in North Guilford, Connecticut, and Grinnell, Iowa.

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.